Introduction

Introduction

Russian General of cavalry Levin Bennigsen, ran his tongue along his thin lower lip not wishing to waste any of the warming spirit he had just sipped from his flask. It was 5.30 am on the morning of the 10th June 1807, and although the days became stiflingly hot and oppressive the nights and the early mornings still harbored the cold and damp. Bennigsen made a half turn in the saddle to study the faces of his staff who were drawn up a little way behind him, then drove his spurs into the flanks of his horse and rode towards a mound of freshly turned earth which was being constructed into the form of a field fortification.

The Polish countryside gave readily to the spade and the pick; the sandy soil was easily compacted into substantial walls that were capable of absorbing cannon and musket balls. Bennigsen had supervised the construction of a whole line of redoubts and earthworks across the open rolling country just northwest of the little town of Heilsberg on the River Alle, in what was then Prussian territory. The whole position had been prepared in the early spring and was now being strengthened still further as the Russian army arrayed itself to meet the advancing French forces under their Emperor, and supreme warlord, Napoleon Bonaparte.

After the defeat of the Prussians at the twin battles of Jena and Auerstadt on October 14th 1806, Napoleon’s hopes for a general peace had still not materialised, although he was master of Berlin, his military objectives were far from being realised. As the shattered remnants of the once proud Prussian army fell back towards the Baltic, in an attempt to join forces with their Russian allies, Napoleon soon became aware that what had began as a swift and brilliant campaign now looked as if it would be drawn-out far longer than he had anticipated.

The French Emperor had no wish to fight a protracted war during the winter of 1806 – 1807, as there was urgent business to attend to in Paris, where as soon as he had left on campaign, the usual outbreaks of plotting and intrigue had taken place. His army was also in need of rest and reorganization, and the great expanse of Poland meant that food would always be in short supply, owing to the scattered nature of villages and towns. Morale was also at a low ebb even after their resounding victories over the Prussians, and the average French soldier did not expect to have to go floundering around in the mud and snow of a Polish winter; however with the Russian determination to continue the war, together with Britain’s open hostility towards the French ‘Continental System’, Napoleon saw no other option than to crush the Russian bear before it could get its claws into Europe.

First Encounters

Early in November 1806, bald and short-sighted Marshal of France, Louise Nicholas Davout, soon to become Duc d’Auerstadt, marched his III Corps d’armee into Poland, a country that had been partitioned by Russia, Prussia and Austria in the latter half of the eighteenth century; thereafter the advance of the French, together with the results of Napoleon’s campaigns against all three powers gave new hope to the Polish nobles who had already begun sending deputations to the French Emperor in which they put forward their desires for a restoration of the Polish monarchy. Napoleon’s vague reply came in the form of a nominal share in the administration being doled out to some of the chief nobles, while he himself retained overall control of the military and government.

On the 26th December Marshal Jean Lannes, Duc de Montebello, attacked the Russians at the town of Pultusk with his V Corps, while twelve miles northwest, at Golymin Davouts corps together with the VII Corps under Marshal of France Pierre Francois Charles Augereau, Duc de Castiglione, pushed back the Russian advance guard under General Friedrich Wilhelm, Count Buxhowden.

Neither of these encounters did any real damage to the Russian army, which, at this time, was under the command of old Marshal Alexander Kamenskoi who managed to extricate his forces in very good order, and the truth of the matter was that the French had become overextended. Kamenskoi was content to withdraw northwest, leaving the French groping about in conditions of alternating frost and torrential rain. The roads became quagmires. Soaked to the skin the French waded through a sea of mud; tempers flared which caused Napoleon to attach the sobriquet “grumblers” to his own Guard. On the 29th December Napoleon decided that his troops should enter winter quarters.

Having caught the Russian’s in a state of dispersal, Napoleon’s ‘Manoeuvres on the Narew’ could not be said to be one of his most enlightened plans. True, he had gained some strategical pluses but his cavalry had been rendered useless in supplying information and French artillery never really got into action ‘a la Napoleon’, remaining for the most part suck up to their trunnions in the Polish mire.

The Russian army now began to reorganise, one of the main reasons being the murder of Marshal Kamenskoi by a peasant on 9th January 1807. The command now devolved upon the German mercenary, General of cavalry Leonty (Levin) Leontyevich, Graf von Bennigsen, who had been in Russian service since 1773. Bennigsen had carved out a distinguished career in the cavalry before coming to the attention of Tsar Alexander I, not least, it was said, because of his part in the assassination of Alexander’s father, Tsar Paul I. Bennigsen’s looks have been described as: ‘ a pale, withered personage of high stature and cold appearance with a scar across his face’.

The new Russian commander had noted that the French left wing was scattered over an extended area and now put together a plan based on a surprise attack on that part of their position in the direction of Hohenstein. If this advance was successful the Russian’s would be able to force the French beyond the Vistula River and make it possible for a fresh offensive in the spring, driving them back to the River Oder. In part, Bennigsen was assisted in his plan by the premature advance of Marshal Michel Ney’s French VI Corps who, on the 2nd January 1807, under the pretext of trying to find better winter quarters for his men, had pushed on to within thirty miles of the town of Konigsburg. Bennigsen had been informed of this movement and now broke the winter truce. With the Prussian Corps under General Lestocq on his right flank, he moved forward to cut off the French I Corps of Marshal Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, prince of Ponto Corvo who had become isolated by Ney’s movement. Bernadotte managed to extricate himself from the trap and repulsed the Russian’s at Mohrungun; thereafter he fell back towards Strasburg.

Upon being informed of Ney’s unauthorized repositioning, Napoleon flew into one of his rages – leaving the beautiful Polish Countess Marie Walewska to keep his bed warm – the Emperor quit Warsaw on the 30th January to rejoin his army; thereafter a series of maneuvers were undertaken by both armies, culminating in the bloody and indecisive battle of Eylau on the 7th – 8th February 1807 in which some 25,000 men were killed or wounded on both sides.

Once again the French and Russians took up winter quarters, owing to the fact that a sudden thaw had once again turned the whole countryside into a vast morass. The French fell back to cover Danzig, which they were besieging, while Benningsen set up his headquarters at Bartenstein. Both armies now took steps to make good their losses.

The Armies

The Russian army that fought at Heilsberg had no corps system during this period and was made up of nine divisions, the first being the Guard. Each division contained one regiment of grenadiers, four regiments of musketeers, one regiment of Jäger (light infantry), two heavy and one light cavalry regiments together with four or five batteries of artillery of twelve guns each. A division had a ‘normal’ strength of around 12,000 men but this number had been greatly reduced by the losses incurred during the previous heavy marching and fighting, so that, counting the Cossacks, engineers and the artillery reserve, Benningsen could muster around 80,000 troops, including some Prussian contingents of cavalry and artillery.

Before the battle of Austerliz (2nd December 1805), General Mikhail Hilarionovich Golenishev-Kutusov had written: ‘ Do not look for any kind of beauty, or burden the men with anything which might detract from the essentials of the business’. Thus the green uniformed Russian infantry had a basic three deep line for each battalion, while the “manoeuver” was conducted in column of platoons, or double platoons; each battalion comprised four companies and each company was sub-divided into two platoons. The campaign strength of a battalion was about 700 men and three battalions formed a regiment.

Russian regular cavalry was made up of Hussar, Uhlan (Lancers), Dragoon and Cuirassier regiments. Each regiment fielded five squadrons of approximately 100-120 men per squadron. Two or three regiments formed a brigade. The normal formation for cavalry squadrons was in two lines, but Hussar and Uhlan regiments sometimes manoeuverd in smaller groups so as to avoid losses from enemy musket fire. The “heavies” – Dragoons and Cuirassiers charged with the straight sword in two lines per squadron which, owing to the effect of artillery fire, tended to cause them to bunch-up on one another, becoming one vast mass of flesh and steel.

The Cossacks, who numbered several thousands, were good light horsemen but tended to shy away from a full-blown engagement with anything other than a disorganized body of troops.

In artillery the Russian’s almost always had a preponderance over the French. The army was completely re-equipped with new cannon in 1805, from 3 pdr to 6 pdr up to the 12 pdr heavy pieces as well as the 10 and 20 pdr ‘licornes’ which were howitzers with a flatter trajectory than the smaller caliber cannon. The name, ‘licorne’ derived from the lifting handles on the top of the gun barrel, which were formed in the shape of prancing unicorns. Counting the 3 pdr guns, of which there were one or two per battalion, the Russian’s fielded over 400 cannon as well as a vast wagon and ammunition park of over 4,000 vehicles.

Napoleon’s army was basically the legacy left to him by the French revolution, which had been forced to raise masses of conscripts in order to meet the threat of invasion from the English Channel to the Alps. The aristocratic officer class of the Ancien Regime were in exile, in prison, or dead, and the regular army had disintegrated; therefore it had become a matter of improvisation and blundering on that brought about the ‘Levee-en-Masse’ being introduced in order to confront the large armies of the various foreign powers who were closing in on France.

Thanks to the tactics that had been experimented with over the last decades of the eighteenth century, when the floodgates opened over the Revolutionary French Government in 1792, they had a formation with which to meet the professionally drilled armies of the European powers – the column.

Light infantry companies were pushed forward to form a skirmishing line in front of the main column of attack. These columns were normally formed by battalions, close packed with a frontage of 50 –75 metres, at one metre or so per man, and to a depth that could vary from 15 –25 metres, depending on the proportion to the front, advancing leaving a gap of around 150 metres to allow the skirmishing companies to fall back just prior to the moment of contact to form a reserve or to protect a flank.

The column moved forward at a normal walking pace with senior officers to the front, while the step was beaten out on the drums. At something like one hundred paces from the enemy’s line the roll of the drum would change to the thunder of the ‘pas –de- charge’, and the column would make a sudden dash into the enemy ranks. Normally the sheer impact and weight of numbers would break the enemy’s line.

A French army corps could number anything from 10,000 – 30,000 men. Each corps was a small army in itself comprising from two to four, or even more divisions, each of two of four brigades which, in turn, contained one to three regiments of two battalions each. A battalion on active campaign numbered around 600 –800 men. Each Corps also contained a light cavalry division or brigade together with the corps artillery of some 30 cannon.

French cavalry were good and consisted, like their counterparts in the Russian army, of heavy and light regiments. No lancer units were introduced until 1811 with the exception of “Polish” lancers which Napoleon, impressed by the skill of the Austrian and Russian Uhlans, raised for his guard. The heavy regiments comprised of cuirassiers and carabiniers who were usually held back to form a central reserve. Being mounted on large, heavy horses, their prime function was shock action. The cuirassiers were equipped with a steel breast and back plate, while the carabiniers did not adopt armour until 1809.

Dragoons were used in several ways, including fighting on foot but their main function, after 1805, was to charge with their companions in the heavy units. Hussars and Chasseurs à Cheval were the standard light cavalry used primarily for scouting and guarding the flanks. They could however be used in a full-blown charge when circumstances dictated. Both the light and heavy regiments were made-up of four squadrons each, these in turn containing 100-120 men per squadron.

In artillery the French had what was arguably the finest system in Europe. However, with the outbreak of war in 1805 the 6 pdr cannon, which Napoleon had hoped to use as a replacement for the 4 pdr and 8 pdr guns, were found to have faults which caused there eventual abandonment. Foot artillery were supplied with 4,6 and 8 pdr cannon as well as 6 inch howitzers. The 12-pdr guns were used, in the main, for mass battery fire and it was not unusual for the French to combine captured artillery into their corps parks. Soult’s Corps, for example, had 48 pieces of ordnance in the 1807, 42 of which were captured from the Austrians during the 1805 Austerlitz campaign.

Although outnumbering the Russian’s in Poland, Napoleon could only muster about 35,000 troops at Heilsberg, including 8,000 cavalry.

Preliminaries

Despite sporadic outbreaks of fighting, all remained quite during the period after the bloody battle of Eylau, with only the siege of Danzig fixing Napoleon’s attention in the Polish theatre. On 1st April 1807 he moved his headquarters to the town of Frinkenstein. The weather now improved and by 11th May reports began to come in from French outposts that the Russian’s were on the move, perhaps with the intention of raising the siege of Danzig. However, on 27th May Marshal Francois Lefebvre, in charge of the siege, had forced the Russian Marshal, Kalkreuth to surrender the city, thus securing the rear areas of the French army against any operations from the sea.

On 5th June Benningsen took the offensive. The Prussians under General Lestocq advanced prematurely to attack the French I Corps of Bernadotte. The plan was badly executed and the Prussians were driven back to Mehlsack, while a Russian division under General Kamenski [1]Not to be confused with Marshal Kamenski, who had been killed. on Lestocq’s left flank was stalled at Lomitten. The forces under Bennigsen did manage to drive back Ney’s II Corps causing some losses, but the red headed French Marshal managed to consolidate and halt the Russian’s at Queetz.

Napoleon now decided to advance on Koenigsberg, moving along the left bank of the River Alle, and in so doing effectively cutting off the Russian’s from their main base and communications. Each French corps was ordered to replenish all ammunition as well as being required to requisition all fodder and food from their immediate area.

On 9th June the flamboyant and gaudy French Marshal, Joachim Murat, with four cavalry divisions and closely followed by the corps of Marshals Lannes, Ney and Soult entered the town of Guttstedt that evening at 7.00 pm.

Bennigsen meanwhile was drawing together his army at the camp at Heilsberg, while General Pierre Bagration covered his fall back with a large rearguard.

The Russian position at Heilsberg was now very strong. The town itself straddles the River Alle, the marketplace and main buildings, including a castle built by the Tutonic Knights on the left bank of the river, with a poorer suburb on the right. To the north, south and east of the town the land rises to form a semi-circle of high ground which dominates this part of the country. The River Alle bisects this high ground about one mile below Heilsberg. To the right of the river the ridge sweeps back in a steep curve until it falls away to a boggy stream which connects with the Alle at Heilsberg. On this bank the heights become more prominent and together with the nature of the ground at their furthest extremities, made it extremely difficult for them to be turned by an attacking army. To the left of the Alle the ridge is less of an obstacle and culminates at a large lake near the village of Grossendorf, some 3,000 meters north of Heilsberg. Both sides of the ridge to the east, or Russian side were dotted with small woods, while to the west, or French side they were bare and presented an almost glacis appearance.

Bennigsen had made full use of every fold of the terrain. On the left of the Alle he had constructed large redoubts capable of holding between 10 to 20 cannon each. On this side, about 500 metres from the river on a tongue of high ground running west was redoubt No 1, a massive structure some ten feet high with walls twelve feet thick. Inside, the earth was sloped up to the parapet upon which the cannon were placed. Strong timbers supported both the inner and outer walls. About 900 metres further north, on the same line, came redoubt No 2 constructed in a similar fashion. Redoubt No 3 was situated 1500 metres to the right rear of redoubt No 2, and facing slightly to the north and had the added advantage of having breastworks thrown up on both sides to facilitate defense. Across the Koenigsberg road another, smaller redoubt protected the extreme right flank, about 500 yards from the Grossendorf lake. Two or three ‘ fléches’ or arrow shaped earthworks interspersed the main redoubts controlling the ground that could not be covered by their fire.

To the right of the Alle similar redoubts, some twelve in number, together with smaller fieldworks covered this part of the line.

Sloping away from the Russian position to the west the ground became open rolling plain; some turned over to agriculture, much left as pasture. A small stream, the Spuilbach meanders across this space from the north to the Alle. The village and wood of Lawden were on the left of the Spuilbach, about 4,000 metres to the northwest of Heilsberg, and about 900 metres southwest again from Lawden was the village of Langwiese; from here at a similar distance and on the same line west stood the village of Bewernick. The main road from Guttstadt to Hielsberg passes close to Bewernick and intersects with the Mehlshack road about 3,000 meters from Heilsberg.

Along the fortified high ground on both sides of the Alle, Bennigsen formed his army in line of battle. Near the left bank stood the Russian 8th division in battalion column. On their right the 6th division continued the line in similar formation linking with the 4th and 5th divisions at the rear of redoubt No2. Prussian cavalry were also massed with Russian mounted units to the right of the 5th division. Behind these formations, at about 200 metres distance, a large force of 12 battalions were grouped in three columns, consisting of troops taken from the main divisions, and placed here for counter attacks. Redoubt No 1 was garrisoned by four battalions while General Kamenski held ten more in and to the left and right of redoubts No 2 and No 3; each of these containing 16 and 14 cannon respectively. Cossack units were spread out around Grossendorf and well north of the lake.

The right bank of the Alle, being the least part of the Russian position to come under serious attack owing to its strength and situation, was gradually stripped of its defenders during the battle, the Russian 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 7th and 14th divisions crossing over to the left bank leaving only a few regiments of infantry and cavalry on the right bank. The five bridges in Heilsberg itself were supplemented by a further six pontoons connecting each bank and facilitating the passage of large bodies of troops.

The Batttle

At around 9.30 am on the morning of 10th June Bennigsen’s outposts reported the French advancing on the left bank of the Alle. From the direction of Guttstadt. Bagration, at that time on the right bank of the river with the rearguard, was ordered to cross over to the left and join forces with a small Russian force under General Barasdin and contain the French advance. Barasdin’s soldiers were falling back before the mass of French cavalry under Marshal Joachim Murat who had advanced ahead of the main infantry units early that morning. All this had taken some considerable time, with Murat’s troopers coming into line piecemeal owing to the distribution of their advance. By 12 .00 am Bagration’s arrival on the field near Bewernick succored Barasdin’s troops and stabilized the line as the Russian infantry deployed to meet the French advance, the Russian cavalry in close support.

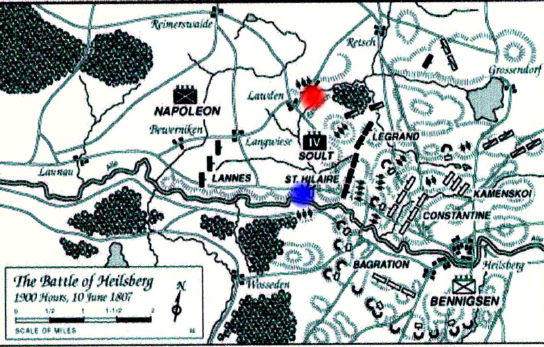

As Murat’s cavalry closed on the Russian line they were stalled by a heavy fire from Russian batteries concentrated around Bewernick village. His own horse artillery fire proving ineffective, Murat awaited the arrival of Marshal Nicolas Jean de Dieu Soults corps, at that time just debouching onto the field, for assistance. Soults first two divisions, under Generals Carra-Saint-Cyr and General Saint-Hilaire, together with his the corps light cavalry, deployed about 400 metres from Bewernick while the bulk of his artillery, some 36 guns, came into action against the Russian batteries causing them to withdraw, thus allowing the French infantry to advance on the village while Soults third division, under General Claude Legrand now came into line and moved on the village of Langwiese.

St. Cyr’s division cleared the Russian’s out of Bewernick at 3.00 pm after heavy fighting, but was forced to call on assistance form General St. Hilaire’s division as Bagration reformed his line for a counter-attack. While these events were taking place, Murat had moved his cavalry towards Langwiese, hoping to fall upon the Russian’s as they fell back from the village, now under threat of being outflanked by Legrand’s regiments. Seeing the movement of Murat’s cavalry, Bagration threw his own troopers into the fray before the French could deploy. In all, around 25 squadrons of Russian horse smashed into the massed divisions of French cavalry, sending them back in disorder and capturing two cannons. At the same time Bennigsen himself had ordered another 25 squadrons of cavalry (including 15 squadrons of Prussians), Dragoons, Cuirassiers and Hussars, under General F.P.Uvarov to move forward and aid Bagrations beleaguered forces while three regiments of Jäger moved to occupy Lawden village. These troops, finding that the French had already taken possession of the village, took up a strong defensive line at the Lawden wood; Uvarov then moved his squadrons to support Bagration’s much battered infantry line which was once more falling back before pressure from St. Cyr’s division.

Swerving away from the French musket fire Uvarov’s troopers moved to their right, smashing into the jumbled mass of Murat’s cavalry who were still endeavoring to sort themselves out after their clash with Bagration’s squadrons. In this massive mélée the French cavalry were once again forced back in confusion to Langwiese.

It was at this stage of the battle that Napoleon, who had been on the field since 10.00 am, but had remained strangely inactive, sent forward General Anne-Jean Savary with two regiments of his Imperial Guard fusiliers and a strong battery of artillery to support Murat. Having to pass through a very narrow defile, which Savary had noted was the only line of retreat for Murat’s horsemen, the French general quickly deployed his regiments in front of Langwiese village, just in time to allow the retreating squadrons of French to filter through his lines and reform at the rear. Still coming on directly behind Murat’s bewildered cavalry the Russian massed squadrons came under a lashing fire from Savary’s infantry and supporting artillery. Leaving the ground covered with dead and wounded men and horses the Russian’s fell back in order to reform. Poor Savary now received a severe tongue lashing from Murat who reprimanded him with strong language for refusing to advance and clear the ground to his front. Savary, in turn, but with all the tact and training of a diplomat, explained quietly that there were strong forces of Russian infantry, together with artillery supports now deploying against him, and that it would be rash in the extreme to move forward until the French cavalry had re-grouped. Murat rode away, cursing, and the fact of the matter was that he owed the salvation of his cavalry to the timely arrival of Savary’s regiments who, together with fresh squadrons sent forward by Napoleon, had taken the pressure off Murat’s jumbled troopers.

With the repulse of the Russian cavalry Bagration was compelled to draw-in his line, and with the massed divisions of French cavalry, now re-formed, he saw no option but to pull back behind the Spuilbach stream.

At 6.30 pm his forces crossed the Spuilbach in some disorder, wagons and gun teams became intermixed all trying to sort themselves out and reform a new line. It was only the timely action of the Tsar’s brother, Grand Duke Constantine, that managed to save Bagrations forces from destruction. Constantine had been in command of the Russian Imperial Guard at the battle of Austerliz and had fought in many engagements, only to die of cholera in 1831. Ugly, brutish and never popular both within and outside the army, he had renounced his right to succession of the Russian throne so that he could marry the Polish Countess Grudzinska. Ever on the alert, Constantine, who had been posted on the right bank of the Alle with his guard division, now ordered four batteries of artillery to move to a point opposite the confluence of the Spuilbach stream and open fire. Some 40 Russian cannon swept the left bank of the Alle and caused the French divisions of St. Cyr and St. Hilaire, who were moving forward to cross the stream, to compress their columns to avoid the awful cannonade. The fire of Constantine’s guns gave Bagration a chance to re-establish his battle line. Only St. Hilaire’s division managed, after heavy loss, to cross the Spuilbach while St. Cyr shook his men out and tried to re-establish order in their ranks. The battle here now became a firefight as the Russian and French volleyed one another while their cavalry re-formed.

On the French left flank Legrand’s division had begun to advance against the Lawden wood, having secured Lawden village and allowed time for Savary’s regiments to advance to his support. The Russian Jäger regiments that had been placed in the wood gave a good account of themselves and extended their line to the right and left as the French endeavored to outflank them. Only after losing over 1,000 men did the Russian’s fall back, in good order, allowing the French to occupy the wood, which became a invaluable support to their left flank.

It was now 5.30 pm and for more than seven hours Bagration, together with Uvarov’s cavalry and Jägers had held back everything that the French had thrown against them. Bennigsen now ordered them to fall back, which they did preserving their formations. Totally worn-out by the severe fighting and marching they had sustained over the last few days Bagration’s brave infantry marched off along the main road towards Heilsberg, crossing the Alle to the right bank and taking up a reserve position. The hard fighting Jägers also moved towards the Alle, but did not cross over, and took station in a fieldwork close to the river. Uvarov’s cavalry, their horses blown, withdrew to the Russian right wing, gathering up Bagration’s troopers as they retired. Bagration himself, covered with dirt and his uniform singed with powder burns but still full of fight, joined general Kamenskoi in redoubt No 3. At 6.00 pm the field in front of the main Russian position was cleared of their forces.

During Bagration’s retirement Bennigsen had ordered the 3rd, 7th and 14th divisions to cross over the Alle to the left bank, soon to be followed by the 1st and 2nd divisions who formed a general reserve behind redoubts No 1 and 2.

The Russian artillery now opened on the French with more than 150 cannon. Not being able to reply to this with any real effect the French had little option but to attack. St. Hilaire’s division, with St Cyr’s division and Murat’s cavalry in support, moved on redoubt No 1 on the right wing.

On the left General Legrand and General Savary advanced on redoubt No 2, the 26th light infantry regiment of Legrand’s division leading the way. With heads bent as if they were struggling through a rainstorm the 26th were hit by the most murderous fire from canister and musketry. Closing the gaps in their ranks and stepping over the mangled bodies of their comrades the 26th took the redoubt at around 7.00 pm. Here they endeavored to consolidate their gains before the inevitable Russian counterattack. This came in the form of three powerful infantry regiments, the Kaluga, Sonsk and Perm, each of three battalions, or close to 4,500 men. The 26th light, together with a six-gun battery and two captured Russian guns opened a steady fire on the advancing green uniformed masses. With their first volley the French brought down almost the entire first two ranks of the Perm regiment as well as killing the Russian general, Warneck. Despite this terrible fire the Russian’s drove out the French at the point of the bayonet. While the Perm regiment hit the redoubt full on, the Sonks and Kaluga regiments moved left and right of the work to take it in flank and rear. Fired at from all sides the 26th light fell back in disorder, taking with them in their flight the 55th line regiment which St. Hilaire had sent from his left to bolster the position. At the moment the Russian infantry re-took redoubt No 2 Bennigsen sent forward a mass of Prussian cavalry including units from the Zieten dragoons and the Tawarzyc hussars. This glittering mass of horsemen charged in on the right of the redoubt, there catching General Jean-Louis Espagne’s French cuirassier division as it came forward to support Legrand’s battle line. The French cavalry gave as good as they received for a time but were eventually forced back behind Savary’s fusilier regiments. Shearing off to the left in order to avoid the French musket fire, the Prussian cavalry now burst upon the disordered ranks of the 26th light and the 55th line regiments. Cutting and slashing right and left the horsemen hewed a bloody path through the disordered French infantry, capturing the “eagle” of the 55th regiment in the process. Only with the arrival of fresh French cavalry the Prussian’s, at last, were forced to retire.

The whole left wing of the French army was now in utter confusion. Savary and Legrand had managed to form most of their infantry into squares as the Russian cavalry rampaged around them, and they now withdrew their whole line back across the Spuilbach stream. The timely arrival on the field of General Verdier’s division of Marshal Lannes corps, together with the musket and cannon fire from St. Hilaire’s division managed to stabilize the situation and avoid total ruin.

Having his hands full with his attack on redoubt No 1, as well as having to contend with his left flank being exposed by the withdrawal of Legrand and Savary, St. Hilaire had no option but to conform with the general retirement. St. Cyr’s division also moved back across the Spuilbach, placing his troops in square formation behind St. Hilaire’s left rear.

The Russian’s now also fell back to their own main lines after once more securing redoubt No 2, but allowing the French to remain masters of the Lawden wood. At 9.00 pm the battle looked as if it war over.

Marshal Lannes, however, was far from convinced that the French were yet finished. One of Napoleon’s true friends, the hard-bitten Marshal, without it seems consulting the Emperor, made up his mind to send in one more attack. He formed General Verdier’s division into column and moved it forward over the darkening plain against redoubt No 2. Bennigsen had been warned of this attack by a French deserter and had covered the approaches to the redoubt with masses of infantry and over 60 cannon. Verdier’s battalions melted away under a withering fire to which they could make hardly any response. After losing over 1,600 men Verdier pulled his division back to the outskirts of the Lawden wood.

The last action took place on the extreme left flank where the 18th line regiment of Legrand’s division had moved against Grossendorf in an attempt to cut Bennigsen’s communications. The Cossacks posted here, together with regular cavalry regiments managed to totally bottle-up the French, and only with the arrival of two battalions and a battery sent by Legrand, were they able to pull back to their own lines. Not to be outdone, the Russian’s also followed up this withdrawal by moving two Jäger battalions against the Lawden wood, only to be forced back after a fire-fight in which they were enfiladed by French horse artillery. The battle now faded away with sporadic gunfire at around 11.00 pm.

The whole plain from the Lawden wood to the River Alle, from Langwiese and Bewernick across the Spuilbach stream and up to and beyond the Russian redoubts was covered in dead and wounded men and horses. Arms, legs, heads and torsos lay everywhere, together with broken muskets, helmets, knapsacks, shakos, straps and bits of food and paper, all now becoming soaking wet as a heavy rain began to fall. Stripped by the peasants and soldiers alike, the corpses were piled four or five deep in front of the redoubts. Along the Spuilbach stream many had drown while trying to reach water by others crawling over them as they drank. The River Alle was bedecked with bodies on both banks while others floated down on the lazy current. It may never be possible to give an accurate figure for the losses incurred on both sides, but most sources agree that the French lost at least 10,000, and the total could have been as high as 12-13,000; while the Russian’s admitted to 3,000 killed and 8,000 wounded and these too could have numbered more in the region of 12-14,000.

The whole battle had proved that Napoleon’s military skills were on the wane well before 1812. He allowed his commanders to do their own thing and was not on top of events. Twenty-four more hours and he would have had most of his army on the field. He also had every chance to outmaneuver the Russian’s by cutting them off from Koenigsberg as most of the French forces were on the left bank of the Alle and in position to hold Bennigsen at Heilsberg while placing themselves squarely across the Russian line of retreat.

The actions of “le beau sabreue”, Marshal Murat, during the battle was less than inspiring. He managed to bungle almost every chance to combine his cavalry with the movements of the infantry, and left Espagne’s cavalry division out on a limb on the French left wing with no apparent orders for that general to co-ordinate his splendid cuirassiers with Savary’s or Legrand’s regiments. Also for Marshal Lannes to risk a whole division during almost total darkness, for no other reason than to prove to everyone on the field that he had arrived, was no more than childish bravado.

All in all the great battle of Heilsberg was only the dress rehearsal for Napoleon’s famous victory at Friedland only four days later, on 14th June 1807. What Heilsberg did prove was the resilience of the fighting men on both sides. In those days of sheer foot slogging over vast distances while trying to keep body and soul together and at the same time being prepared, at any moment to fight for their lives, one cannot but admire the spirit and tenacity of those men. Heilsberg has been sadly overlooked by many who would rather bath in the light of Napoleon’s more dazzling exploits. Suffice it to say that, if only for the sake of those brave men who now lie under the soil of modern Poland, without any visible markers which so much dominate other fields of glory, they are worthy of their small place in history.

Graham J.Morris September 2003

Further Reading.

Chandler D. The Campaigns of Napoleon. London: Wiedenfeld and Nicholson 1966.

Petre F. Lorraine. Napoleon’s Campaign in Poland 1806-07. London: Greenhill Books 1989.

Wilson. Sir Robert. Campaigns in Poland 1806 and 1807. Felling: Worley Publications 1995.

References

| ↑1 | Not to be confused with Marshal Kamenski, who had been killed. |

|---|

Some good information on this page but the notion that the six pounder DID not replace the 8lb and 4lb guns is in error. In fact it was used throughout the rest of the Napoleonic Wars right up to and after Waterloo. Not sure where you got the idea that it was abandoned because if was found faulty. The horse artillery missed their beloved 8lb guns but in fact the 6lb gun ended up having better effect on the battlefield because its rate of fire was much higher than the 8lber and its casualty rate over a similar amount of time was better.

But we need more articles on these obscure battles. Heilsberg was a battle that should have been stopped by Napoloen. In almost “Trump-like” fashion he blamed everyone else for the failure. Truman would have said, “the buck stops here.”

Thanks for visiting the site Bill!

My apologies for the 6 pdr cannon error; info from a source I cannot now recall, maybe an old Tradition magazine, they were always making slight mistakes.

I agree about the more obscure battles in history and intend to visit a few more before I cash in my chips!

Best regards,

Graham (Battlefield Anomalies)