29th – 30th August 1813,

In June 2013 Gramo and DrBob visited the site of the Battle of Kulm in the Czech republic. Armed with nothing more than a compass and camera and fortified by a McDonalds breakfast, 10 chicken wings and a chesse salad, they spent two days travelling around the battlefield. Despite the distant rumbles of thunder, they took over 400 photographs.

These have been stitched into a fully interactive virtual tour. A full account of the battle, complete with newly prepared maps is shown on the following pages.

View the tour here.

For those who prefer a more traditional approach to history, the article is available as a short monograph priced £5.00 & pp. Please contact Graham for more details.

For other accounts of the battle and descriptions of the locality see these links:

http://cs.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bitva_u_Chlumce_(1813) (English translation)

http://napoleon-knihy.blogspot.co.uk/2010/07/bitva-u-chlumce-prestanova.html (English translation)

http://www.prestanov.cz/bitva-u-chlumce-a-prestanova/d-4648 (English Translation)

Jiri Bures has asked me to add a link to his site dedicated to the battles of Chlumec, Přestanov and Varvažo. Jiri lives locally and organises re-enactments each year. Use this link to get translation to english by google translate

The Lost Opportunity.

A New Command.

General of Division, Dominique-Joseph-René Vandamme, count of Unsebourg, looking clean and dapper in a new uniform, mounted his horse and said farewell to his wife and child. He had been forced to leave Napoleon’s Grande Armée during the summer of 1812, just as the fateful Russian campaign was underway, owing to his constant bickering and insubordination towards the French Emperor’s younger brother, Jérôme Bonaparte, King of Westphalia. Now, after cooling his heels on his estate near Cassel in northern France during the autumn and winter of 1812-1813, Vandamme found himself back in favour with Napoleon, mainly due to the appalling losses in officers and men incurred during the disastrous advance and retreat from Moscow. Knowing full well Vandamme’s skill as a division commander, plus the urgent need to build a new and powerful army in order to reassert his control over his wavering allies, Napoleon had ordered his minister of war to write to the general and ask him to return to duty. Only too happy to oblige, in late February 1813, Vandamme rode away to take up his post as commander of three new divisions forming between the Weser and Elbe Rivers, these troops would be used to bolster the depleted French forces on the lower Elbe. [1]Gallaher. John G, Napoleon’s Enfant Terrible, page 230.

With his prestige seriously dented, his once proud army reduced to rag – pickers, and his allies considering their options, only a man of Napoleon’s willpower, determination and ego could have shrugged off the disastrous 1812 Russian campaign and set about building a new Grande Armée in order to reassert his authority in Europe. By the early spring of 1813 he had created twelve army corps, and although most of the infantry regiments were made up of raw recruits, and the cavalry very weak for wont of horses and proper training, it was still, nevertheless, a fantastic achievement.

Russia and Prussia

The hardships and losses of 1812 were not confined to the French army. Russia had also suffered severely. Her army, in particular, was much reduced and its equipment in need of refurbishment. In early February 1813 many of the infantry regiments were down to one battalion, and these contained fewer than 400 men each, while the cavalry had shrunk from the established eight squadrons per regiment down to four, with no more than 80-100 men per squadron; in all, counting the artillery and Cossacks, around 110,000 men. On 5th February a “ukase” had prescribed the formation of a reserve army of 163 battalions, 92 squadrons and 37 batteries of artillery, to be assembled around Bialystock. From March to August 1813 this reserve supplied the field army with 68,000 infantry, 14,000 cavalry, and 5 batteries of artillery. [2]Petre. Lorraine F, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page 26

The effect of the Russian victory in 1812, over the seemingly invincible French emperor, first surfaced when the Prussian contingent serving as part of the Grande Armée, under general Hans David Ludwig von York, defected to the Russians by signing the Treaty of Tauroggen (30th December 1812). Thereafter the Prussian king, Frederick William III, signed the Treaty of Kalisch (3rd February 1813) with Russia, agreeing to surrender the land acquired by Prussia during the third partition of Poland to the Tsar, in return for Russia’s proliferation of the war against Napoleon until Prussia’s pre 1806 position had been restored.

The Prussian army of 1813 was undergoing a rapid increase in strength. With the signing of the Kalisch treaty an edict was issued for volunteer Jäger aged between 17 and 24, and a Landwehr militia of all men from the age of 17 to 40 to be integrated into local units. [3]Rothenberg. Gunther E, The Art of Warfare in the Age of Napoleon, page. 194 The regular Prussian forces, which had been limited to 42,000 men by the Treaty of Tilsit (7th July 1807), formed the backbone of the new army. Thanks to the diligent work of General Gerhard Johann von Scharnhorst, a “Krumper” system had been set up allowing each company and squadron in the regular army to discharge a specific number of trained troops, and bring in an equal number of recruits for training. It was due to this constant flow of men that the restrictions placed on the size of the army by Napoleon were circumvented, allowing a further 33,642 trained men to join the colours. [4]Petre. Lorraine F, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany, page. 22. See also the detailed account of Scharnhorst’s reforms in Dr Charles E. White’s work, The Enlightened Soldier, Westport … Continue reading Therefore, counting various “Free Corps” units, plus artillery, the Prussians were eventually able to raise a force of around 120,000 men. The main problem, especially during the opening stages of the 1813 campaign, was the lack of weapons, uniforms, shoes and provisions; not to mention the fact that many of the fresh recruits were in need of drill and training. The Landwehr in particular suffered severely:

…Raised jointly by the provisional and royal authorities, its units were formed on a local and regional basis, with the provincial colours on their cap band and flags and the Maltese cross as their cap insignia. Up to the rank of captain, officers were elected whilst the higher grades were proposed by estates and appointed by the king. At first the Landwher lacked officers and equipment. Muskets were in short supply and pikes had to be issued to many of the troops. Overcoats, blankets, and packs were lacking, and some units were barefoot. As late as October 1813, one regiment, poor weavers from Hirschberg in Silesia, had no boots. Even so, the militia fought with unexpected élan during the 1813 campaign, though, like the early levies of the French Revolution; the militiamen were undisciplined, given to sudden panic and desertion. And like the French levies, they eventually learned to fight by fighting and to march by marching. [5]Rothenberg. Gunther E, The Art of Warfare in the Age of Napoleon, page. 195

The Austrian auxiliary force, which had also been committed to aiding Napoleon’s main thrust against Russia, slipped quietly away into Galicia once it became apparent that things had gone badly wrong for the French, not wishing to take sides until being sure of backing the winner. Thereafter Austria adopted a stance of armed neutrality, cloaking her real intentions under the mantel of offering to play mediator between Napoleon and the Russians and Prussians.

The Spring Campaign of 1813.

Never happy with the idea of continuing the war by advancing into Germany in the first place, the Russian commander, Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov, coming under pressure from the Tsar, reluctantly ordered a concentration of his forces along the line of the river Elbe. The old soldier was not keen to keep pushing forward when he knew full well that Napoleon would soon take advantage of Russia’s weak and extended line of communication: ‘You must understand that any reverse will be a big blow to Russia’s prestige in Germany.’ [6]Beskrovnyi (ed.), Pokhod, no 131, Kutuzov to Winzengerode, 24th March/5th April 1813, p.132. Quoted in Lieven.Dominic. Russia against Napoleon, The Battle for Europe 1807 to 1814, page. 309 Lacking the troop numbers and resources available at this time Kutuzov was probably right, however by holding the line of the Elbe rather than taking up a position further west the Russians and Prussians allowed Napoleon more time, a luxury they themselves required in order to attempt to bring Austria in on their side and also allow much needed reinforcements to arrive from Russia. [7]Ibid, page.310

On 28th April Kutuzov died and the Tsar replaced him with general count Ludwig Adolf Peter Wittgenstein. Why Wittgenstein was picked for the job has remained something of a mystery. He was chosen most probably because the Tsar wanted to be seen as the man who rid Europe of the Corsican ogre, and he certainly resented Kutuzov being lorded as the ‘saviour of Russia.’ [8]Lawford. James, Napoleon, The Last Campaigns 1813-15, page.17 As for Wittgenstein himself, although he had fought with distinction during the Polish War (1794-95), and at the battles of Austerlitz (1805); Friedland (1807), and Polotsk (1812), he nevertheless was way out of his depth commanding anything larger than an army corps and eventually he was replaced and pushed into the background; when the Austrians finally joined the coalition he had virtually nothing to command, his forces having been split – up. [9]Ibid, page.17

During the last days of April, Napoleon, with some 100,000 men of the Army of the Main, began to advance on Leipzig from the direction of Erfurt, while The Army of the Elbe, under Prince Eugéne, Napoleon’s stepson, and numbering around 30,000, approached from the direction of Halle in the north. The Russian and Prussian combined army of some 86,000 men were grouped just south of the French line of march, near the town of Lutzen. Here, on the 2nd May, Wittgenstein, aware that Napoleon was gradually building up his forces and would eventually outnumber the combined allied army, decided to strike the French before they could concentrate superior forces against him. The brave but reckless French Marshal Michel Ney, Duke of Elchingen and Prince of the Moskva, guarding the French right wing, was dilatory in his behaviour in not conforming to Napoleon’s orders for the concentration of his five divisions and to send out strong recognisance forces to determine the whereabouts of the enemy. On the 2nd May Wittgenstein attacked Ney’s III Corps scattered around the villages of Starsiedel and Grossgörschen south – east of Leipzig and a bloody but indecisive battle was fought. Although the allies were forced to retreat, the victory claimed by Napoleon did little more than bring the wavering Saxon king, Frederick Augustus I, back into an alliance with the French.

The orderly retreat of the Russians and Prussians after the battle enabled them to cross the Elbe River and take up a strong defensive position around the town of Bautzen in eastern Saxony. Here they were able to draw breath and consolidate, constructing a number of strong redoubts and entrenchments on the high ground behind the valley of the Blösaer Wasser River with troops pushed forward along the line of the Spree River and around Bautzen itself to fight a stalling advanced guard action; the combined strength of the allied army being some 96,000 men.

After the battle of Lutzen, Napoleon had rearranged his forces; disbanding the Army of the Elbe, he now created a new army under Ney numbering 84,000, while he himself commanded the main army, including the Guard, of almost 120,000. With the latter he engaged the allies at Bautzen in a containing battle on the 20th May. The following day Ney’s army came down on their right flank for the kill. However, due once again to Ney’s mishandling of the situation, which can only be attributed as the knock – on effect of Napoleon’s failure to place a less excitable and hot headed general in command of so large a force, the allies were able to make good their escape.

Although they had managed to evade defeat on two occasions, the Prussians and Russians were far from being in agreement on the actual course of action now to be taken. Barclay de Tolly now replaced Wittgenstein as commander – in – chief owing to the latter’s total mismanagement of affairs at all levels, and the alliance was held together tentatively, mainly by Tsar Alexander, who suggested that the army should retire in a south – easterly direction, covering Silesia and therefore being able to keep in touch with Austria whose intervention on the allied side was now fast becoming a necessity. [10]For full details of the French and Allied manoeuvres after Bautzen, together with the state of the opposing armies see Petre. F Loraine, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page. 142 – 159. … Continue reading

On the 4th June, Napoleon, totally out of character in comparison to his former blustering concerning the plight the allies must be in after their twin defeats at his hand, agreed to an armistice. He also agreed to a Peace Congress to be held in Prague, his reasoning being his lack of cavalry and his uncertainty concerning the position of Austria.

With the benefit of hindsight it could be said that, on the one hand, Napoleon should have kept up the pressure. His lack of cavalry had not hampered him a great deal during the early stages of the campaign, indeed, it was his massive weight of infantry numbers that had swung the balance in his favour at both Lutzen and Bautzen, and given the fact that for the most part they were untried and untested in battle, they had fought splendidly. On the other hand, these same young recruits were worn out by forced marches and were unaccustomed to the French style of bivouacking, which meant sleeping where one could and foraging what was available. This, in turn, caused a colossal wastage from sickness and exhaustion. There was also the problem of defending the French line of communication, which required a substantial amount of manpower as large raiding parties of Cossacks were operating in the French rear area. With all this being said, Napoleon himself later stated that agreeing to an armistice was one of his gravest mistakes. By continuing to keep up the pressure and driving hard close on the heels of the undefeated but wavering and weary allied army he may indeed have secured a favourable peace very much on his own terms. The euphoria in the allied camp on hearing of Napoleon’s decision to agree to an armistice was the release – valve for the problems and pressure that had been building up over the previous months. When General Louis Andrault Alexandre de Langeron, a French noble who had entered Russian service at the beginning of the French Revolution, announced the news at Barclay’s headquarters it was received with great peals of laughter ‘…this explosion of happiness,’ wrote Langeron, ‘was by no means normal with Barclay. He was always cold, serious and severe in spirit and in his manner. The two of us laughed together at Napoleon’s expense. Barclay, all the generals and our monarchs were drunk with joy and they were right to be so.’ [11]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 327 – 328

Prelude to Disaster

While Napoleon had been engaged in fighting the Russians and Prussians, general Vandamme was organizing a fledgling corps of three divisions to reinforce the depleted French forces on the lower Elbe River. The important city of Hamburg had been captured by Colonel Freiherr Ferdinand von Tettenborn commanding a small “free corps” of Cossacks and regular cavalry in March 1813, the French general in charge of the city, Claude Carra Saint – Cyr, having quitted the place and retired southwest, much to Napoleon’s displeasure. Vandamme was duly ordered to retake it, as it was the key to the lower Elbe region. However, before he could complete the training and organization of his new command Napoleon had placed Marshal Louis Davout in charge of the Thirty – Second Military District, which included Hamburg and all troops in the northern sector. Treating each other with respect deferential to each other’s rank and military performance, but without any show of friendship, Davout and Vandamme worked well together, the Marshal allowing Vandamme to proceed with retaking Hamburg, which fell to the French on 30th May. [12]Gallaher. John G, Napoleon’s Enfant Terrible, page. 230 – 234

Prior to his reoccupation of Hamburg, Davout had received orders from Napoleon that as soon as the city was once again in French hands he was to “send General Vandamme with the Second and Fifth divisions and the necessary artillery in the direction of Mecklenburg and Berlin to cover the left flank of the corps that is advancing on Berlin.” [13]Quoted in; Gallaher. John G, Napoleon’s Enfant Terrible, page. 238 As things turned out Vandamme became drawn ever closer to the centre of gravity around Napoleon himself, but as we shall see with the unfolding of events, he never came under the direct orders of the Emperor on the battlefield, and he certainly made better use of his skills as a general than the other commanders given independent control of large forces by Napoleon.

The Plan that Never Worked

All parties involved realised that the Armistice of Neumarckt was nothing more than a temporary pause in a campaign that could only be decided either by Napoleon regaining his former control over Europe, or by the an allied victory that would push him firmly back across the Rhine, the Pyrenees and the Alps, confining him once and for all to the boundaries of France and ridding their lands of his menacing presence. To this end Austria, although appearing to play the part of mediator between the allied Coalition and the French emperor, was in fact preparing and strengthening her forces ready to throw in her lot on the side of the allies. Even the Austrian minister, Prince Clemens Lothar Metternich, who was sent to negotiate the peace talks, was well aware that Napoleon would never accept his proposals to give up all he had gained over the past thirteen years. Also negotiations taking place in Prague proved to be only a sham played out while all sides prepared for a renewal of the conflict, and the armistice was renounced on the 10th August with Austria joining the Coalition against France two days later.The vacillating and cunning Prince Charles John, Crown Prince of Sweden, former French Marshal Jean – Baptisie – Jules Bernadotte, also threw in his lot with the allies, although his motives were far from clear.

The combined allied forces ranged against Napoleon were massed in three armies:

| The Army Of Bohemia | |

|---|---|

| Commander: | Prince Karl Philipp Schwarzenberg |

| Austrians: | 125,000 |

| Prussian II Corps: | 37,000 Kleist |

| Prussian Guard: | 7,000 |

| Russians: | 80,000 Barclay de Tolly |

| TOTAL: | 249,000 |

| The Army Of The North | |

| Commander: | Crown Prince of Sweden |

| Prussians: | 72,000 Tauentzien/Bulow |

| Russians | 30,000 Winzingerode |

| Swedes | 23,000 Bernadotte |

| TOTAL: | 125,000 |

| The Army Of Silesia | |

| Commander: | Field Marshal Gebhard von Blücher |

| Prussians: | 38,000 Yorck |

| Russians | 370,000 Sacken/Langeron |

| TOTAL: | 108,000 |

| GRAND TOTAL: | 482,000 |

After much hot air being expanded at a conference at the castle of Trachenberg, the Allies finally decided on a plan of operation that would entail each of their respective armies not accepting battle with the French when Napoleon himself was in command, but rather to fall back until such time that their combined forces manoeuvring against his centre of operations would outnumber him on the field.

During the armistice Vandamme was placed in command of the newly designated 1st Corps of the Grande Armée, with his headquarters at Magdeburg. He now had some forty battalions of infantry in three divisions, together with forty – six cannon, in all close to 25,000 men, [14]Gallaher. John G, Napoleon’s Enfant Terrible, page. 241. See appendix A for details However, the source material available for Vandamme’s corps at this time is conflicting.

The French army now numbered, not counting the troops holding the garrisons of the Elbe, Oder and Vistula Rivers, approximately 440,000 men, including almost 30,000 cavalry. With these Napoleon intended to concentrate the main army, under his personal control, in a strategically defensive position running from Bautzen to Görlitz, with entrenched camps around his centre of operations at Dresden and also at Königstein. These forces consisted of the I., II. III., VI., XI., and XIV corps together with the 1st, 2nd, 4th, and 5th cavalry corps and the Imperial Guard; around 300,000 men. Marshal Charles – Nicolas Oudinot, Duke of Reggio, would move to threaten Berlin with a force of around 80,000 men, consisting of IV, VII, and XII corps, plus the 3rd cavalry corps, while Marshal Davout with 40,000 men (including 15,000 Danish troops) would also advance toward the Prussian capital , ‘…drawing on himself as many as possible of the enemy. Between Davout and Oudinot would be Dombrowski with 3,000 or 4,000 Poles and [general] Girard with 8,000 or 9,000 men. Altogether there would be about 120,000 men moving concentrically on Berlin.’ [15]Petre F.Loraine, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page. 171

To act on the defensive went totally against Napoleon’s principles of warfare, and thus he chose to strike first and fast against his old enemy, the wily old Prussian hussar, Field -Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher and his Army of Silesia, which had moved prematurely before the actual deadline for the end of the armistice, and which, in turn, diverted Napoleon’s attention away from other plans of action in order to meet the threat. Probably without much enthusiasm for retiring without a fight Blücher, in accordance with the Trachenberg Plan, pulled back out of Napoleon’s reach, causing the French to strike into a void. On 23rd August the French emperor, on obtaining the news that Schwazenberg and the Army of Bohemia were advancing, abandoned his quest to bring Blücher to battle and marched back to Dresden, leaving Marshal Étienne MacDonald, Duke of Taranto, with a force of 90,000 men to shadow his elusive pray.

Before commencing his maneuvering against Blücher, Napoleon had received information that a large force of Russians under Wittgenstein was marching to join the Army of Bohemia, and he even contemplated attacking these forces, writing to Vandamme, whose advance units were just arriving at Stolpen, to move his corps to Rumburg. Here he would find the 42nd division belonging to Marshal Laurent Gouvion St Cyr, which was to be attached to Vandamme’s command providing that St Cyr himself were not hard pressed. There were also some 3,000 cavalry of the French Imperial Guard under General Charles Lefebvre – Desnouettes, which he was also to have. He continued, “It is possible I might enter Bohemia at once and fall upon the Russians and catch them ‘en flagrant délit.’ ” [16]Corr. 20,408, to Vandamme, Quoted in, Petre F.Loraine, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page, 186 Thereafter Napoleon changed his mind and set his troops in motion to attack Blücher, leaving Vandamme with orders to fortify himself in the passes around Rumburg, here he would also receive help from Marshal Claude Victor, Duke of Belluno’s II Corps, together with the small Polish VIII Corps under Prince Josef Anton Poniatowski, newly created Marshal of the Empire. These 65,000 men Napoleon considered sufficient to hold the passes until he had destroyed the Army of Silesia.

The crucial stage of the campaign came on 25th August when Napoleon received an urgent message from Marshal St Cyr, informing him that his XIV Corps of some 20,000 men were about to be attacked at Dresden by the entire Army of Bohemia which had crossed the Erzgebirge Mountains. Napoleon had been contemplating a thrust against the rear of Schwarzenburg’s army by way of Pirna stating in a ciphered dispatch sent to St Cyr on the 24th August:

“My intention is to move to Stolpen. My army will be assembled there tomorrow. I shall spend the 26th there in preparation, and rallying my columns. On the 26th, in the night, I will send my columns by Königstein, and at daybreak on the 27th, I shall be in the camp at Pirna with 100,000 men. I shall operate so that the attack on Hellendorf begins at 7 A.M., and I shall be master of that place by noon. Then I shall place myself astride of that communication, and seize Pirna. I shall have two bridges ready to throw at Pirna, if necessary. Either the enemy has taken as his line of operation the road from Peterswalde to Dresden, in which case I shall be in his rear with all my army opposed to him, whilst he cannot assemble his in less than four or five days; or he has taken his line of operations by the road from Kommotau to Leipzig. In that case he will not retire, and will move on Kommotau; Dresden will be relived, and I shall find myself in Bohemia, nearer than the enemy to Prague, on which I shall march. Marshal St – Cyr will follow the enemy as soon as he appears to be disconcerted. I shall mask this movement by lining the bank of the Elbe with 30,000 cavalry and light artillery, so that the enemy, seeing all the river lined, will believe my army to be at Dresden… I assume that, when I undertake my attack, Dresden will not be attacked so as to be able to taken in twenty – four hours.” [17]Corr. 20,449, dated Görlitz, 24th August. Quoted in, Petre F.Loraine, page. 191

As things turned out the allied army was already closing in on Dresden, albeit without much show of haste, and the time wasted by the constant disagreements between the various monarchs and their advisors and generals concerning the correct plan of attack led them to lose precious time in organizing a quick and decisive assault before Napoleon could reach the field. Also the weather, which had been fine, became increasingly cold and wet during the evening of 26th August. The increasing wind accompanied by torrential rain began to cause rivers to rise rapidly, and turned roads and meadowland into quagmires of mud.

On the afternoon of 25th August Napoleon, now convinced that Dresden was in imminent danger of being attacked and captured by the Army of Bohemia, sent fresh orders to Vandamme with instructions to move his corps onto the Köenigstein Plateau and thereafter capture and occupy the town of Pirna on the River Elbe. In the meantime the Emperor himself would march to the relief of Dresden.

One can see that, although Napoleon had shelved the plan of marching against the rear of the Army of Bohemia with his main army, he nevertheless considered that Vandamme’s I Corp could still execute a similar manoeuvre, causing problems for the Allies if they were to be forced back into the defiles of the Erzgebirge Mountains, which indeed proved to be the case.

The battle of Dresden fought on the 26th – 27th August was, arguably, the last great encounter which could have altered not only the fate of Europe, but also the destiny of Napoleon himself. The two day battle fought on the second day in the most appalling conditions of mud and driving rain was, for the Allies, a fiasco which led to the loss of almost 30,000 men, in killed, wounded and prisoners, together with much material and baggage. Now was the time for Napoleon to throw everything he had into a pursuit that would have shattered the Army of Bohemia. Also, given the fact that all three Allied monarchs were with the defeated army, and would have been struggling to make good their escape before themselves becoming prisoners of war, it was certainly the French emperor’s best hope of ending the campaign in the style of Austerlitz and Jena. What he did do proved too little too late, and the fact that he fumbled and then dropped this golden opportunity, only goes to shows how much his military prowess had declined when confronted with making swift and decisive decisions on the grand scale that these vast campaigns required.

‘I will be master of Pirna tomorrow at an early hour’

Cognizant to the orders received from Napoleon on the 26th August to, ‘…advance to Basra and Hellendorf so that you can occupy the passes and fall on the rear of the enemy,’ [18]Gallaher. John G, Napoleon’s Enfant Terrible, page. 243 Vandamme, although informing Napoleon that he was perplexed as to the whereabouts of his heavy artillery (12 pounders) which, for reasons never fully disclosed had been sent to Dresden, nevertheless began to bridge the Elbe and push his corps across to engage the enemy.* These consisted of the Russian Second Corps and the 14th Infantry Division from the First Corps, together with four squadrons of regular cavalry and a detachment of Cossacks, plus 26 pieces of artillery, commanded by Prince Eugen of Württemberg and numbering around 13,000 men. They had been detached from Wittgenstein’s column as it advanced on the Teplitz road towards Dresden to keep watch on the Elbe near Königstein. [19]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 397 – 398. There are no detail of where, and indeed if, Vandamme collected the French bridging train on the march, or if the pontoons were … Continue reading

The young French recruits, bolstered by a few hard – core veterans scattered throughout the various battalions and regiments under Vandamme’s command, were wet and hungry, but nevertheless still full of fight, albeit only to be guaranteed for a limited period, and buoyed by the news filtering in of the imminent return of their emperor and his Guard to Dresden; their spirits rose as they began to march across the rocking pontoons to confront the enemy, Vandamme informing Napoleon by dispatch that he would be, ‘master of Pirna tomorrow at an early hour.’ [20]Gallaher. John G, Napoleon’s Enfant Terrible, page. 243

Russian troops line of retreat to Kulm (white) . French 1st Corps follow up to Kulm (black).

Württemberg was well aware of Vandamme’s superiority in numbers and called for assistance from both Wittgenstein and Barclay de Tolly, but fully realising that this would take some time to materialise, he made preparations to fight a delaying action until help arrived. He did receive a temporary loan from the Grand Duke Constantine, the Tsar’s brother, who was marching with his corps along the Teplitz main highway on the morning of the 26th August on his way to join in the attack on Dresden. He dropped off the Empress’s Own Cuirassier Regiment under the command of Prince Leopold of Saxe – Coburg (the future king of Belgium), with instructions that they should be returned later that evening. Besides this Prince Eugen realised that, owing to the strung out state of Vandamme’s corps as it funnelled across the pontoons, he would be able to slow its deployment for some time with his artillery, owing to the wooded nature of the ground the French would have to negotiate after crossing the Elbe. [21]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 398

These Russian tactics worked well, the French not being able, for some inexplicable reason, to get their artillery into action until late in the day. This allowed Württemberg’s gunners to lay down an unimpeded curtain of fire which crippled every attempt by the enemy to get through the woods and form for an attack. As evening approached on the 26th August, despite having inflicted over 1,800 casualties and held up Vandamme’s corp for a whole day, Württemberg fully realised that with his own losses close to 1,600 men, he would have to withdraw or be overwhelmed. This proved somewhat of a dilemma, as he could not cover both the allied right flank from being attacked by Vandamme, and the route back to Bohemia down the Teplitz highroad that the allies would require as a line of retreat if they were beaten at Dresden. Not knowing what the outcome would be, Württemberg therefore chose to hold up Vandamme as long as possible and stop him marching northward and coming down on the allied flank. [22]Ibid, page. 398 – 399

In the most atrocious conditions the battle of Dresden slogged on throughout the 27th August, heavy rain preventing muskets from functioning and mud slowing down movement. Towards the end of the day it became obvious that the allies had suffered a serious defeat, their only option being to save what they could and retire back over the mountains into Bohemia. To this end Schwarzenberg ordered the army to retreat in three separate columns. The left wing, to march west to Freiberg, then south – west towards Commotau, the second column of the army would fall back through Dippoldiswalde where they would split, part moving to Frauenstein, part on Altenberg thence on to Dux in Bohemia. The third column, and the largest, containing mostly Russian troops and some Prussian units, would take the road south – eastward towards Dohna, thence to Berggieshubel and from there though Peterswalde and on to Teplitz. [23]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 399 – 400 Like all seemingly straightforward orders in war, these movements proved totally impractical owing to the bottleneck that would have been created on the allied left along the Freiberg road, which was already cut by the French, and therefore forced them to divert south – west to Pretschendorf, and thereafter part moved via Dux, while others took the road to Marienberg, and then on to Commotau. The allied central column, consisting mainly of Austrian troops, had moved off on the evening of the 27th August, and made good its escape to Dippoldiswalde, however, the Russians and Prussians making up the allied column on the right wing, under Field – Marshal Prince Barclay de Tolly and Field – Marshal Count Friedrich von Kleist, chose to ignore their marching orders, and instead of taking the Teplitz road as instructed, which would have placed them in a position to be caught in a vice between Vandamme and any troops sent by Napoleon to pursue them, caused the Russians to strike out directly down the Dippoldiswalde highway to Altenberg, while the Prussians took the ‘Old Teplitz Road’ going through Maxen, Glashütte and Barenstein, across the Erzgebirge Mountains, then descending down into the valley by way of Graupen. All of this caused much confusion and exhausted the poor troops who, after fighting and losing a futile battle over the course of two days in the most appalling conditions, were now herded along like cattle, many losing their boots in the glutinous mud, without hope of a respite from their fatigue and hunger until they had cleared the mountain defiles. [24]Ibid, page. 401 For a more detailed account see also, Petre F. Lorraine, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page. 227 – 230

With the allies in full retreat Napoleon, as he had done on former occasions, should have thrown everything he had into a full blown follow up pursuit, that he failed to do so, even allowing for the fact that rumour had just reached him of the defeat of two of his Marshals at the battles of the Katzbach ( Marshal MacDonald on the 26th August), and Gross – Beeren (Marshal Nicolas Oudinot, Duke of Reggio on the 20th – 23rd August), he nevertheless could do nothing to alter the situation, therefore now should have been the time to keep on the enemies heels, which would, in all probability, if he had placed himself in the vanguard, have resulted in the total ruin of the Army of Bohemia and may well have forced Austria out of the war. Indeed, his initial orders for the follow up of the defeated and battered enemy columns appeared substantial, providing the momentum was kept up – it wasn’t. Marshal Adolphe Mortier, Duke of Treviso, with two divisions of the Young Guard, together with Marshal St Cyr’s mauled but intact XIV Corps were to march on the road to Peterswalde and couple up with Vandamme’s forces. Marshal Auguste Marmont, Duke of Ragusa, with his VI Corps, to take the road to Altenberg, while the dashing but vain King of Naples, Joachim Murat, together with the II Corps under Marshal Victor, would advance along the road towards Freiberg. Napoleon himself even moved forward as far as Pirna on the 28th August, after which he took himself off back to Dresden, where news of the twin defeats suffered by MacDonald and Oudinot was confirmed, thus allowing the impetus to go out of the chase.

‘all that which marches in the tail of his army’

Meanwhile, on the morning of the 27th August, after finally getting all of his forces across the Elbe and into line, albeit with some loss, Vandamme now had at his disposal, not counting the losses incurred during the previous days fighting, some 37,000 men. He placed the detached brigade of the 23rd Division, under General Joachim – Jérôme Quiot du Passage, on the plateau near Pirna, with a battalion of the 85th Line Regiment on the Kohlberg heights. On Quiot’s left stood the 42nd Infantry Division (detached from XIV Corps) of General Régis Barthélemy Mouton – Duvernet, with the 2nd Infantry Division of General Jean – Baptiste Domonceau continuing the line again to the left where the 1st Infantry Division of General Armand Philippon together with the 1st Light Cavalry Division under General Jean – Baptiste – Juvénal Corbineau held ground towards the village of Hennersdorf. The brigade of infantry commanded by Prince Henry LXI of Kostritz, attached to Vandamme’s corps from the 5th Infantry Division, together with the 21st Light Cavalry Brigade under General Martin – Alexis Gobrecht were drawn up in reserve behind Phillippon’s division. Although his heavy guns had still not arrived from Dresden, Vandamme had some 76 pieces of artillery now up and ready to take on the Russian batteries. The problem facing the 1st Corps commander was his lack of knowledge concerning the overall military situation. Napoleon’s orders to Vandamme were ambiguous to say the least. The general had complied with the order received on the 26th August to attack the enemy corps before him, being informed that the emperor himself was engaged in a battle at Dresden. He was then ordered to march on to Hellendorf as soon as possible, with the added directive that, “I hope that during the day you will find yourself in the rear of the enemy.” [25]Gallaher. John G, Napoleon’s Enfant Terrible, page. 244 However, on the 27th August Vandamme, for some inexplicable reason never fully understood, never used the full weight of his command to brush Württemberg aside and march – on into the Teplitz valley. Instead he seems to have been at a loss to know just what the Russians were doing, or, indeed, where to strike at them. Also further orders received from Napoleon on the afternoon of the 28th August appear to contradict the previous ones concerning getting ahead of the enemy and now:

“The Emperor orders that you direct your movements towards Peterswald with the entirety of your corps, Corbineau’s (cavalry) division, the 42nd Division (Mounton – Duvernet of the XIV Corps), and the brigade of the II Corps commanded by Reuss. This will give you an augmentation of 18 battalions.Pirna shall be guarded by the troops of the Duke of Trévise (Mortier), who shall arrive there this evening. The marshal also has orders to relieve your position in the Lilienstein camp. GB (General of Brigade) Baltus (I Corps artillery) with your 12pdr battery and your park, shall arrive in Pirna this evening. The Emperor desires that you unite all the forces that he has put at your disposition and that with them you penetrate into Bohemia and throw back Prince Wüttemberg, if he chooses to oppose you. The enemy that we have beaten is withdrawing on Annaberg. His Majesty thinks that you should arrive before him on his lines of communications with Tetschen, Aussig and Teplitz, and take his equipment, his ambulances, his baggage, and, in the end, all that which marches in the tail of his army. The Emperor orders that the pontoon bridge at Pirna be raised so that another may be erected at Tetschen.” [26] Nafziger, George. Napoleon’s Dresden Campaign; The Battles of August 1813, page. 205 – 206. For more details see Appendix B

From the above order one can see that the blocking of the defiles into Bohemia is not part of Vandamme’s remit, rather, he is told to push back Württemberg and cut his line of communication. How Napoleon expected Vandamme to take possession of “all that which marches in the tail of his army” when he was supposed to be clearing a path for himself to get ahead of it is somewhat confusing. Obviously the emperor was expecting more from Marshal St Cyr and Murat than he in fact got. But it is strange that, given that his orders to Vandamme only mention dealing with Wüttembergs command, then how he was to supposed to capture all of the allied armies baggage and equipment, which was moving by several different routes, is hard to understand.

‘leading the advance with drums beating.’

For his part Württemberg fully understood the urgent need to try and stop Vandamme from blocking the defiles of the Erzgebirge Mountains and cutting off the escape route of the Russian and Prussian columns. He had been reinforced by 6,700 men of Major – General Baron Gregor von Rosen’s Ist Guards Infantry Division, which comprised some of the finest regiments in the Russian army, the Semenovsky, Preobrazhensky, Izmaiovsky and Guard Jäger, accompanied by a company of Guard marines. These troops, together with the overall commander of the entire Guard Corps, General Alesksei Ermolov and his staff, were a much needed addition to Württemberg’s tired and hungry soldiers. The problem was that their arrival coincided with a less welcome newcomer turning up, in the person of General Count Ostermann – Tolstoy, who arrived on the 26th August with orders from the Tsar stating that he was to take command of all allied troops on the right. [27]Lieven, Dominic. Russia against Napoleon, page. 403 Ostermann was a strange man. Good looking with an air of the Byronic about him, he took the title of Count Ostermann, plus enormous estates and wealth from an uncle who was childless. He was brave, some said foolhardy, but nevertheless a presence on the battlefield that was well respected by the troops. He participated in almost every major engagement that Russia fought against Napoleon, sometimes going on campaign with his pet white crow and Eastern Imperial eagle. His dashing appearance and steadiness on the battlefield unfortunately did not compensate for his lack of military talent when it came to commanding anything larger than a division, and upon returning to the army in the spring of 1813, after a bout of illness, some noted that he was inclined to become over excited, which, in turn, was attributed to an unbalanced frame of mind. [28]Lieven, Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 404 Quoting from the memoirs of Colonel von Helldorf and Eugen of Wüttemberg, Lieven states that the army knew of Ostermann – Tolstoy’s mental … Continue reading

The first crisis occurred when, on the 27th August, after taking command, Ostermann received orders from Barclay de Tolly stating that if he thought that continuing down the main Teplitz road could be hazardous, then he should abandon it and seek another route of escape across the mountains. Given his mental state and his lack of any real understanding of the military situation, the panic driven Ostermann chose to quit the highway and cut across to join the other allied column marching down the Dippoldiswalde road. As Petre states:

Had these orders been carried out, the result would have been the meeting of 120,000 men on a single bad road from Dippoldiswalde to Bohemia. The resulting confusion would have been almost unimaginable, and by the time the crowd of disordered troops reached the passes leading down to Bohemia, Vandamme would have arrived at their mouths, via Peterswalde, quite unopposed. [29]Petre, F.Lorraine, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page. 229

Fortunately for the allies, Eugen of Wüttemberg, who was a first cousin to the Tsar, flatly refused to comply with Ostermann’s orders, pointing out the danger and the need to block Vandamme’s route so that the other allied columns could make good their escape. Luckily he was supported in his views by general Ermolov, who was in possession of a good map of the area, which he used to explain to Ostermann the need to stay on the Teplitz highroad. Finally and only after Wüttemberg had promised to take full responsibility for whatever occurred, did the dithering count agree to keep to the road and try to slow down Vandamme’s progress. [30]Lieven, Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 404

As previously stated, Vandamme had done nothing on the 27th August to try and cut the Teplitz highway, this in turn had allowed a great amount of the Russian baggage to get safely away into Bohemia. On the 28th August, believing that Marshal St Cyr was marching to unite with him and join in the chase, and after receiving Napoleon’s missive to “fall upon the prince of Wüttemberg,” Vandamme began to move, fighting off a heavy diversionary attack put in by the Russians around Krieschwitz, and finally advancing to Hellendorf. Here, at 8:30 p.m., he sent a message to Napoleon stating that he had “driven the enemy south with heavy losses and I will attack again at daybreak and march on Teplitz with my entire force unless I receive orders to the contrary.” [31]Gallaher, John. G, Napoleon’s Enfant Terrible, page. 246 There is no doubt that Napoleon approved of what was taking place, writing to Murat on the 29th August that, “He is leading the advance with drums beating. They (the enemy) are all Russians. General Vandamme marches on Teplitz with his entire corps.” [32]Ibid, page. 246

‘in whatever direction it would take’

The Russians under Ostermann and Wüttemberg had put up a gallant and effective running rearguard action all the way to Hellendorf. Here, on the morning of the 29th August, with the rain having now stopped and a thick mist rising through the treetops, they once again halted, the Guard Jäger regiment slowing up the French advance long enough for two line infantry regiments to take up battle positions around the village. Not to be denied, and now irritated by the stalling tactics of the enemy Vandamme, well forward with his advanced units at an early hour, sent in Prince Reuss’ brigade in a two column attack against his stubborn and unyielding foe. The handsome 29 year old Prince Henry of Reuss – Schleiz – Koestritz had only been promoted to General of Brigade on 11th July 1813. His family were of the Older Reuss line, his father being Prince Henry (Heinrich) XLIII, and his mother Princess Louise of Reuss – Ebersdorf, her sister Augusta became Queen Victoria’s maternal grandmother. Riding forward with his staff in order see that his regiments and battalions coordinated their attack, Reuss was stuck by a cannon ball on his left thigh, tearing away the upper part of his leg. In excruciating pain he was transported back to Hennsdorf where he died a few agonising hours later. [33]Gallaher, John.G, Napoleon’s Enfant Terrible, page. 246. There is some confusion here regarding Hellendorf and Nollendorf. Petre (page. 233) states that Ruess was killed in the action at … Continue reading

As the bleeding body of Prince Reuss was being carried from the field, Vandamme sent his Chief of Staff, General of Brigade Jean Revest, to take command of his brigade. After a stubborn resistance the Russians fell back to Peterswalde where, due to an order issued by the nervous and panic – minded Ostermann – Tolstoy, their rearguard commander, General Prince Ivan Shakhovskoi was told to hold his ground longer than Wüttemberg had intended, allowing the French time to start encircling the village. Once again the steadfastness of the Russian infantry, coupled with timely cavalry charge headed by Leopold of Saxe – Colberg’s cuirassier regiment, enabled them to extricate themselves and continue the retreat to Nollendorf. [34]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 406.

Fully expecting to be soon supported by Marshal St Cyr with his corps and Marshal Mortier with the Young Guard, Vandamme pressed the attack with vigour. What he did not know, and never would until it was too late, was that although St Cyr had originally been ordered to pursue the enemy (General Frederick Heinrich Kleist’s Prussian corps) towards Dohna. That is to say, he was actually marching on the left bank of the Elbe River, Dohna being only a few miles from Pirna, and therefore he was moving directly towards a link up with Vandamme. Now however, around 2:00 p.m on the afternoon of the 29th August, he received an order from Napoleon stating that, “You will follow the enemy to Maxen and in whatever direction it would take.” This meant that, since Maxen lay to the southwest, and although he would indeed still be following Kleist, albeit that is until he lost contact, he would now be moving away from Dohna and therefore away from Vandamme. [35]Gallaher, John. G, Napoleon’s Enfant Terrible, page. 247 Also, because of the bad news concerning the defeats sustained by his subordinates, Napoleon had halted Mortier’s Young Guard at Pirna. The remaining French pursuit columns under Murat and Marmont, although collecting vast amounts of discarded baggage and equipment, only managed a half – hearted attempt at getting to grips with the retreating allies – Vandamme was on his own.

The 29th of August – Gambit.

On the night of the 28th August Ostermann – Tolstoy sent off a letter to the Emperor of Austria Francis II telling him to quit Teplitz as the French were advancing in great strength towards the town and he was not capable of stopping them. Without needing too much encouragement, Francis packed up and left, leaving a note warning of Ostermann’s tale of gloom and doom for the Prussian King, Frederick William III, who had just arrived himself at Teplitz. Although never much of a rapid decision minded man (his wife had been the forceful one), the Prussian king realised the danger of allowing Vandamme to march unimpeded and seize the mountain defiles leading down to Teplitz. Not only this, but Tsar Alexander himself was still somewhere on the road leading from Altenberg through the Erzgebirge range. Therefore Frederick William sent one of his aides – de – camp’s, Colonel von Natzmer, closely followed, just to make doubly sure, by his military adviser, General von dem Knesebeck, with urgent instructions to stop the French advancing to Teplitz no matter what. These urgent pleas soon made Ostermann aware of the danger, not only to the allied army, but also to the possible safety of his own monarch and he therefore decided to offer battle around the three villages of Priesten, Straden and Karwitz. [36]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 407

The Russian rearguard under Wüttemberg, by a series of bold and heroic actions, had kept Vandamme’s strung – out command at bay in a running fight that had lasted three days. Now, on the morning of the 29th August, with the temperature rising and a thick mist covering the ground, they rejoined the main body which was deployed across the rolling meadows about two kilometres east of Kulm. Here Ostermann and Ermolov intended to use the three villages as breakwaters against the French attacks. To the north Straden, close up against the foothills of the Erzgebirge Mountains, in the centre Priesten, and in the south Karwitz. The ground was of no real importance; for the most part it was open grassland, sparsely cultivated around the villages, each of which contained small gardens and were crisscrossed with tree and shrub lined ditches marking the boundaries between each garden. The houses were mainly constructed around a timber frame with thatch or shingle roofs which, in turn, made them susceptible to being set afire. [37]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 407 – 408

The main road, dropping steeply down out of the mountains, ran through the small town of Kulm and on west through Straden and Priesten towards Teplitz, some seven kilometres further on. To the south of Kulm rose the Strisowitz Heights, quite steep and heavily wooded at the north and south, with pasture land across the east – west central area.

The Russian left, commanded by Ermolov, took ground around Straden with its Leather Chapel and the Sawmill, or Eggenmühle, just to the north. The Guard Jäger and the Murmon Line Infantry Regiment held the houses, barns and gardens, as well as the Sawmill and Leather Chapel while to their rear, in line behind the village, stood the Semenovsky and Izmailovsky Guard Regiments, with the Preobrazhensky Guard Regiment in support. The Guard Light Foot Battery #1 and Guard Heavy Battery #2, 24 cannon in total, were positioned 20 meters in front of the Guard infantry. The Guard Hussar Regiment of 4 squadrons was stationed behind the Semenovsky’s.

In the centre, commanded by Wüttemberg, the village of Priesten was held by elements of the Reval Line Infantry Regiment and the 4th Jäger Regiment, with the main body of both regiments drawn up in column behind the right rear of the village, together with Light Battery #27 and Position Battery #14, 23 guns in all. Also in column on the left rear of the village Major General Helfreich drew up part of the Russian 14th Division consisting of the Tenginsk and Tobolsk Line Infantry Regiments.

The right wing under Prince Dimitri Galitzin was composed mainly of cavalry and extended from the main road at Priesten to the outskirts of Karwitz. Here, from left to right in the first line, stood the 4 squadrons of the Tartar Uhlan Regiment, the 4 squadrons of the Empress Cuirassier Regiment and, on the extreme right of the line, the Illowaiski XII Cossack Regiment. The second line comprised of 2 squadrons of the Austrian Erzherzog Johann Dragoon Regiment, 2 squadrons of the Loubny Hussar Regiment and 2 squadrons of the Sepuchov Uhlan Regiment. In front of the cavalry stood the Guard Horse Battery #1 of 12 cannon. At the beginning of the battle the Russians had fewer than 15,000 men available to hold back over 35,000 French. However they were constantly being reinforced as, thanks to Frederick Williams’s foresight, a steady flow of allied troops had been ordered to concentrate at Priesten. [38]Nafziger. George, Napoleon at Dresden, page. 214 – 215

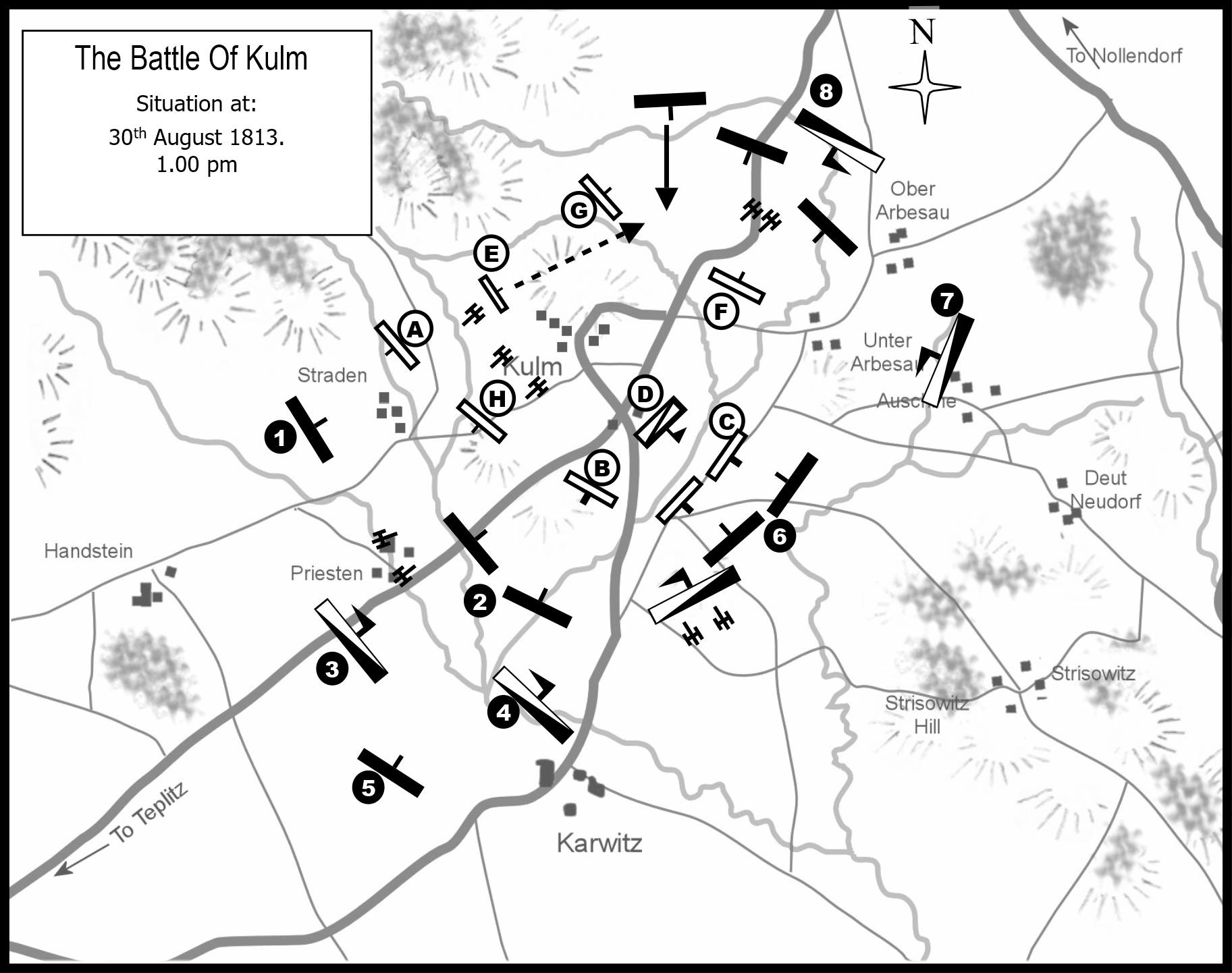

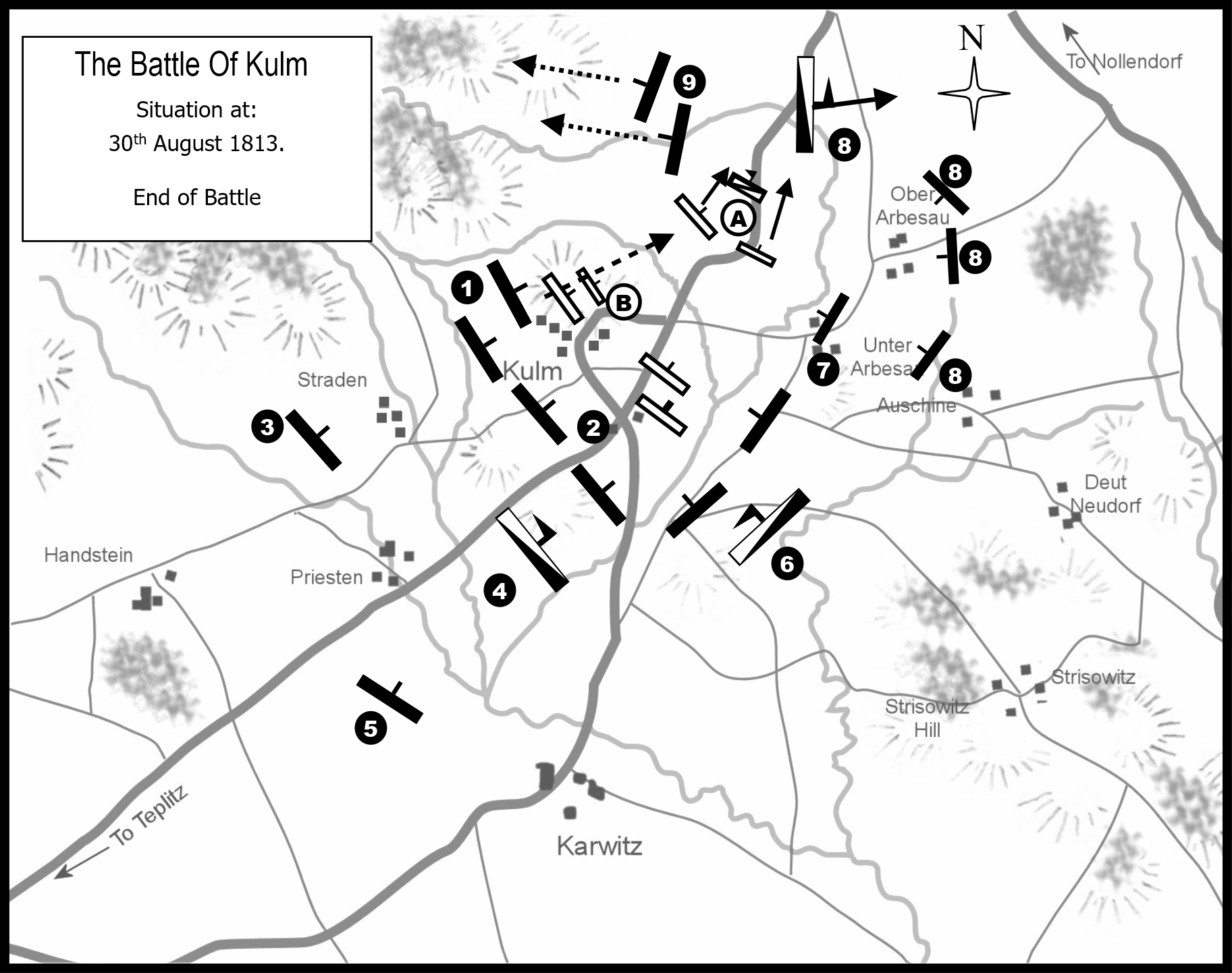

Russians:

1) Murmon Infantry Regiment; Guard Jäger Regiment; Semenovsky Guard Infantry Regiment; Preobragensky Guard Infantry Regiment; Ismailovsky Guard Infantry Regiment; Guard Hussar Regiment.

2) Estonia Infanry Regiment; Grand Duchess Catherine Battalion; Toblosk Infantry Regiment; Tschernigov Infantry Regiment; Minsk Infantry Regiment; Revel Infantry Regiment; 4th Jäger Regiment.

3) Russian cavalry regiments.

French:

A) Revest’s (formely Reuss) 5th Infantry Brigade.

B) Mouton–Duvernet’s 42nd Infantry Division arriving.

At 10:00 a.m. on Sunday 29th August Vandamme’s forward units, consisting of Revest’s brigade, cleared Kulm of the Russian skirmishers, as well as a group of townsfolk retuning from church, the latter running in blind panic across the fields towards Unter Arbesau, the former falling back on their main line. Thereafter an 8pdr foot battery accompanying Revest opened fire from the rising ground just beyond the town, its first salvos being answered by the Russian Guard Horse Battery #1, the smoke from this exchange of fire began to temporarily blot out parts of the landscape.

From his vantage point on the hillside above Kulm, near the Chapel of the Holy Trinity, Vandamme had an excellent view of the battlefield. Now that the weather had cleared and the sun was shining, he could see through his telescope that columns of white uniformed Austrians as well as Green coated Russians were steadily coming down through the mountain defiles in the distance. Taking this as a sign that they were still being pursued by the French follow up forces of either Murat, Marmont or Victor, Vandamme immediately ordered Revest to attack Straden while he sent orders to hurry forward the remainder of his corps. [39]Nafziger, George, Napoleon at Dresden, page. 215

The young conscripts in Revest’s now depleted brigade were damp and dirty, their eyes sunken into their heads through lack of sleep. They had been fighting and marching in rain and mud for days, nevertheless their morale was still high. They had forced the Russians out of one position after another and now they were going to kick them out of this one. Quickly forming into two columns, the 46th Line Regiment on the right, consisting of the three battalions, and the four battalions of the 72nd Line Regiment on the left, both regiments proceeded by a company in skirmishing order, passed through their gun line and began to advance over the rolling meadowland towards Straden. About halfway across they came under fire from the Russian batteries in front of the village firing solid shot, some of which tore bloody lanes through their ranks, but mostly passing harmlessly over their heads due to the soaking wet nature of the ground which, with each firing, gradually dug the gun trails into the soft earth causing the barrels to elevate slightly. Closing ranks the two French regiments continued to press forward until a belch of fire stabbed smoke boiled up around the village issuing from the muzzles of several hundred Russian muskets, and accompanied by a hail of canister shot from their artillery which caused them to falter. General of Brigade Revest, his face bespattered by blood from a canister blast that had riddled the men beside him and maimed and brought down his horse, untangled himself from the harness and proceeded on foot, encouraging his men to close up and go forward, which they did, pressing on into the village and pushing the Russians back to the Sawmill and Leather Chapel. The fighting was severe, with the Murmon regiment and Guard Jäger’s putting in every man to resist the French assault, which finally petered out and ebbed back across the fields as the Semenovsky Guard Regiment came up to support their beleaguered comrades. Not to be denied, and still presenting a bold front to the enemy, Revest’s thinning battalions once more formed to renew the assault, their spirits boosted by the arrival of three fresh regiments of the 42nd Division under General of Division Régis Barthélemy Mouton – Duvernet who, after filing these nine battalions through Kulm, began to form them into heavy columns in preparation for an attack between Straden and Pristen. Duvernet had distinguished himself at Arcola in Italy during Napoleon’s brilliant campaign of 1796 and thereafter had steadily risen in the ranks, becoming general of division just three weeks earlier on the 4th of August 1813. Although not an imposing figure, with his hair brushed well forward to cover his baldness, he was a brave fighting general and a good tactician who would end his days in front of a firing squad in 1816, shot as a traitor for rallying to Napoleon during the Hundred Days.

As Revest once more closed on Straden, Duverent’s troops came across the fields in tight packed battalion columns, this type of massing being one of the ways of ensuring that the recruits, many of whom lacked sufficient training, could be kept together as a coherent force when manoeuvring against the enemy. Unfortunately it also made them a fine target for the Russian artillery. [40]Owing to the rate that troops were being fed into the Napoleonic mincing machine the manoeuvres performed by the veterans with such glorious results at Austerlitz, Jena and Auerstädt had been … Continue reading

As Duvenet’s men were deploying, the 1st Light Cavalry Division under General Jean – Baptiste – Juvénal Corbineau, clattered through the streets of Kulm and took up a position covering the French left flank. He was followed by the 21st Light Cavalry Brigade commanded by General of Brigade Charles Martin Gobrecht who drew out his squadrons just behind the French gun line to the east of the town. Although only light cavalry, these two units comprising hussars, lancers and chasseurs à cheval, were to perform prodigies of valour worthy of any units in the French Imperial Guard.

This time Revest, owing to the depleted state of his battalions, kept his brigade together, heading straight and hard for Straden, which was now on fire in many places and had been evacuated by the Russians who fell back to form a new line to the rear of the smoke billowing village with troops still holding the Sawmill and the Leather Chapel. After receiving a salvo from the Russian artillery, Revest’s troops pressed on through the burning buildings of Straden, with red hot sparks flying in all diredtions, and attempted to dress their ranks and move forward. This proved impossible to achieve owing to the blasting they received as they came within easy range of both canister and musket fire, which caused them to retire once more, leaving another carpeting of dead and wounded piled up on the ground.

On Revest’s left Duvernet’s troops had fared no better. The Tenginsk and Estonia Infantry Regiments, together with the Grand Duchess Catherine Infantry Battalion moved to meet the threat. These troops, supported by the Tobolsk and Chernigov Infantry Regiment went forward with a roar after delivering an unwieldy but still effective volley which, accompanied by a hail of canister from the 23 guns of Light Battery #27 and Position Battery #14, mowed down several hundred of Duvenet’s men, causing the rest to falter and fall back to the protection of their artillery line in front of Kulm. It was now 2:30 p.m., and while Duvernet’s and Revest reorganised and steadied their shaken battalions, the first infantry brigade of General Armand Philippon’s 1st Division arrived on the field, with the second brigade following at some distance. [41]Petre, Nafziger and Lieven all give slightly different accounts of what took place during the battle. Petre states that it was 2:00 p.m when Philippon arrived on the field; Nafziger says he arrived … Continue reading

‘The Prince is a German and doesn’t give a damn…’

Vandamme rode up to meet Philippon personally. His orders for the taking of Straden and Priesten had not been delivered by word of mouth, but in writing carried by members of his staff. He knew full well that Revest, being, until the death of Prince Reuss, his personal Chief – of –Staff, would carry out these orders to the best of his ability, likewise he also trusted Duvernet in needing no personal encouragement to buckle down to the task at hand. However, thus far things had not gone well, mainly due to the fact that the whole of his corps was strung out on the twisting road leading down out of the mountains, and therefore it would take a long time to get everyone onto the battlefield. He also knew that, although he would have to use his troops piecemeal as they came up, he was left with no other option owing to the fact that to await the arrival of his entire force before attempting to shoulder the Russians out of the way might only result in their receiving reinforcements, which he had seen himself pouring from the passes earlier in the day, thus strengthening their position still further. Therefore he felt the need to give Philippon direct instructions while showing him the exact place on the battlefield where his troops would prove most effective.

General of Division Armand Philippon was a rakish looking Norman, born in Rouen. He had just turned 43 years of age on 27th August, and had a reputation for courage and steadiness under fire. He had distinguished himself in Spain where he gained praise from all sides as French Governor of Badajoz and for his defence of the town during the second siege in 1811. Viewing the field though his glass the general now listened intently to what Vandamme was proposing. First, any further attacks would be made in accord by all units, hammering at the Russians all along the front so that they would be unable to spare any troops to shore up their line when a breakthrough became imminent. Secondly, and allowing for the fact that his 12pdr cannon had still not arrived, Vandamme ordered his chief of artillery, General of Brigade Pouilly de Baltus to place two more batteries in line with the ones already in action near Kulm and lay down a concentrated fire that would soften up the Russian position prior to the infantry attack.

At 3:00 p.m. the French guns bucked into action sending a hail of metal crashing into the Russian lines taking off heads, arms and legs and mangling torsos. But as fast as a gap appeared in their formation the stalwart infantry of Mother Russia closed ranks and stood their ground with grim determination awaiting the attack they knew would follow. They didn’t have to wait long. After twenty minutes of pounding the French guns fell silent as the massed battalions of infantry under Revest, Duvernet and Philippon closed on the Russian position.

Revest, taking heavy fire from the Russian Light Battery #27, attacked in two columns, the first, consisting of two battalions of the 42nd Line Regiment, clearing the defenders from the bonfire that was once Straden, went heads down for the wooded Sawmill (Eggenmühle) heights, the other, containing the remaining battalion of the 42nd and the much diminished four battalions of the 72nd Line Regiment came in obliquely between the Sawmill and Priesten, hitting the Russian line formed by the Guard Infantry Regiments. These tough élite troops, many with their feet wrapped in rags after losing their boots in the glutinous mud during the retreat, stopped the French in their tracks, but the two battalions of the 42nd, after successfully clearing the defenders from the Sawmill, poured a heavy and destructive fire into the Russian ranks which caused them to retire, but only momentarily. Seeing the plight of his guards, general Ermolov quickly bought them back to the attack, driving the French back with the bayonet, “and a roar from the throats of a thousand enraged guardsmen.” [42]Nafziger. George, Napoleon at Dresden, page. 217

On Revest’s left, Duvernet and Philippon’s battalions moved against Priesten, Duvernet deploying four battalions of the 22nd and 4th Provisional Light Infantry Regiments on the right of the village, with a further two battalions of the 3rd Provisional Light Infantry Regiment continuing the line linking up with Revest’s left flank. The remainder of his division, now all on the field, and consisting of two battalions of 17th Provisional Line Infantry Regiment, two battalions of the 16th Provisional Line Infantry Regiment and four battalions of the 76th and 96th Line Infantry Regiments were held back in reserve. Duvernet’s divisional artillery of 6 – 6pdr guns and two howitzers were placed in the gun line by Balthus. To the left of Duvernet again came the massed ranks of Philippon’s 1st Brigade, one regiment in mixed order – line and column – the other in compact closed order colonne serrée, this type of formation once again ensuring that the poorly trained recruits could perform simple manoeuvres and be better controlled.

While Duvernet’s troops attempted to cut – in between Straden and Priesten, severing the Russian line, Philippon’s 1st brigade, after sending the 12th Line infantry Regiment to back – up Duvernet’s attack, made straight for Priesten village itself. The brigade was led by General of Brigade Etiénne – Francois – Raymond Pouchelon who, placing himself at the head of the 7th Light Infantry Regiment sent two of its battalions directly into the village, while the remaining two were directed to the right and left of it seeking to pinch – out the Russian defenders. [43]Once again the various sources give different accounts of this phase of the battle. Lieven states that Philippon had four regiments (two brigades) on the field (page 409). Petre gives Philippon … Continue reading ) The defending companies of the Revel and 4th Jäger regiments fell back on their supports who greeted the French with such a murderous fire from musket and canister that they were unable to deploy outside the village. As the torn and tattered 7th Light fell back to regroup Württemberg brought forward two artillery batteries to the left of Priesten, from where they plastered the French formations of Duvernet’s regiments and Pouchelon’s 12th Line Infantry Regiment with a perfect hail of canister in flank and rear causing them to recoil in some disorder. [44]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 409 It was obvious that these guns must be silenced and this task was allocated to the troops of Pouchelon’s 2nd Brigade under General Raymond de Montesquiou Duke of Fezensac who were just arriving on the field.

The Russian line infantry regiments under Württemberg had now all been committed to the battle with no reserves remaining. The prince, in some desperation, pleaded with general Ermolov to let him have the relatively fresh Izmailovsky Guard Regiment to help beat back the next French assault he knew full well was about to break over him. Aleksey Petrovich Ermolov, a bull necked bulk of a man with a face that warned of no compassion, refused outright, creating a bitter argument in which Ermolov cried, ‘The Prince is a German and doesn’t give a damn whether the Russian Guard survive or not: but my duty is to save at least something of his Guard for the emperor.’ Ermolov may have had a point, the Izmailovsky’s having two of the only three remaining battalions still held in reserve, but Württemberg saw the danger far more clearly and realised that sacrifices had to be made. Leaving Ermolov with a curt wave of the hand he rode over to where Ostermann was standing, telescope pressed to his eye watching the French collecting themselves for a fresh assault, and begged him to override Ermolov’s decision. This was granted, and the muddy but upright and proud guardsmen moved forward to meet the threat. [45]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 409

Russians:

1) Russian Guard Regiments and Murmon Infantry Regiment;

2) Toblosk,Tschernigov, Minsk, Revel Infantry Regiments and 4th Jäger and Grand Dutchess Catherine Battalion.

3) Russian cavalry regiments.

French:

A) Revest’s Brigade.

B) Mouton-Duvernet’s 42nd Infantry Divison.

C) Corbineau’s Ist Light Cavalry Division and Gobrecht’s 21st Light Cavalry Brigade.

D) French Gun Line

It was not long in coming. At 4:00 p.m. the French came forward again, Philippon’s 2nd Brigade, consisting of four battalions of the 17th Line Infantry Regiment and two battalions of the 36th Line Infantry Regiment heading straight for Priesten while Duvernet sent forward his relatively unscathed 2nd Brigade under the 33 year old General of Brigade Charles Auguste Creutzer in two attacking columns, the 16th Provisional Line Infantry Regiment’s two battalions against the Leather Chapel and the Sawmill and the 76th and 96th Line Infantry Regiments in four battalions attempting to get around the northern flank of the Russian position by skirting through the wooded foothills. These were soon driven back by the concentrated fire of the Russian Light Battery # 14 and Position Battery#27, moved to the west of Priesten in the nick of time by Württemberg. The French advance on the Leather Chapel and Sawmill grinding to a halt and finally being forced back by a bold counter attack from the Semenovsky and Preobrazhensky Guards. [46]Nafziger. George, Napoleon at Dresden, page. 217

Around Priesten the skeletal battalions of general Shakohovkoy’s 3rd Division and general Helfreich’s 14th Division once more braced themselves to receive the French. Württemberg, even with the aid of the Izmailovsky Guards, knew how desperate his position was. He therefore switched his artillery batteries swiftly from their position covering the west of the village and brought them forward just in front of his infantry line. Their fire, together with a massed volley from the infantry staggered the French leading units, tearing huge gaps in Fezensac’s brigade, causing it to lose momentum. Seizing the opportunity the Izmailovsky’s went in with the bayonet, joined on each side by all of Württemberg’s command who could still put one foot in front of the other. The sight and sound of these dirt and blood caked demons, yelling at the top of their voices as they came at them out of the smoke, proved too much for Fezensac’s young troops, their only thought now being to get away from these mad eyed fiends as quickly as possible, which they did in short order, breaking back to their own lines in some confusion which, once they had cleared their own guns, took a great deal of time to sort out. As if to spite the man who had given his permission for the guard regiment to be used, and to such good effect, a round shot from a French cannon came hurtling over the field tearing off part of Ostermann – Tolstoy’s left arm. As he was being carried to the rear he remarked, ‘I am satisfied. This is the price I paid for the honour of commanding the Guards.’ [47]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 410

‘We have no source of substance.’

The battle in the centre gradually settled down to an artillery duel, with the Russian batteries taking on the French gun line at Kulm. Over on the Russian left the French kept up harassing tactics, Duvernet sending in small scale spoiling attacks, more to keep up the morale of his men than with the intention of doing any real harm; his troops, like the Russians, were in need of rest and sustenance.

Russian:

1) Russian Guard Regiments, Murmon Infantry Regiment and Guard Hussar Regiment.

2) Estonia Infantry Regiment, Grand Duchess Catherine Battalion, Minsk Infantry Regiment, Revel Infantry Regiment, Toblosk Infantry Regiment and Tschernigov Infantry Regiment.

3) Russian cavalry.

French

A) Revest’s Brigade.

B) Mouton–Duvernet’s 42nd Division.

C) Philipons 1st Division.

D) Corbineau’s and Gobrecht’s cavalry.

E) French gun line.

F) Domonceau’s 2nd Division arriving.

It was on the Russian right that the battle now evolved. Vandamme was becoming more and more agitated and impatient. He now ordered Philippon to try and outflank the enemy position by moving around Priesten. The available troops still in reasonably good fightingorder were the four battalions of Pouchelon’s 7th Light Infantry Regiment and part of the 1st Brigade of General of Division Jean – Baptiste Dumonceau’s 2nd Infantry Division, just arrived at Kulm, and consisting of the 13th Light Infantry Regiment, who’s four battalions formed on the right of the 7th Light. These two regiments began to move forward at around 5:00 p.m., crossing the Sernitzbach stream and forming into battalion squares as the Russian cavalry on their right wing moved to hinder the French progress. This was thwarted when Corbineau, already covering the advance of the 7th and 13th Light with a brigade of cavalry on each flank, now bought forward the remainder of his division, forcing the Russian cavalry to retire. This allowed the French infantry to shake itself out back into attack columns which, after receiving a weak cannonade and a peppering of musket fire, finally got into and aroundthe right of the village which was now an inferno of flame. The weak Russian units, almost out of ammunition, had been joined by the last remaining reserve consisting of two companies of the Preobrazhensky Guard Regiment who now endeavoured a spirited but seemingly futile counter attack. The situation changed dramatically when, just as all seemed lost, the Russian Guard cavalry arrived after being held up in the mountain pass at Graupen. These welcome reinforcements were accompanied by the keen eyed and tousle headed, Major General Baron Ivan Ivanovich Diebitsch, a former Prussian officer now in Russian service, who announced, much to Württemberg’s relief and joy, that soon large numbers of fresh infantry would arrive together with more guns and cavalry. [48]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 410

Lieven tells an interesting tale concerning Diebitsch’s arrival on the field:

Nikolai Kovalsky was a young officer of the Guards Dragoons in 1813. He recalls how the regiment was led down narrow and sometimes precipitous paths from the mountains into the Teplitz valley by staff officers and by two local shepherds who acted as guides. Apparently, when Diebitsch rode up to the Guard Dragoons and initially ordered them to charge no one moved because no one knew who he was. Only when he opened his coat and displayed his orders and medals did he get a response. First one dragoon, then more and finally the whole regiment moved forward. Ermolov tried to stop this disorderly attack which he had not authorized but it was too late. Kovalsky records that the French cavalry panicked and fled at their approach and the infantry did the same after just one volley. The weak French response undoubtedly owed much to the fact that while the Guard Dragoons’ were threatening their front the Guard Lancers were driving deep into their right flank and rear. Almost certainly it was the Lancers who did the most serious fighting because while the Dragoons’ losses were relatively modest, the Lancers lost one – third of their officers and men during the battle. [49]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon, page. 410 – 411. Quoting from, ‘Iz zapisok pokoinago general – maiora N.P.Koval’skago,’ Russkii vestnik, 91/1, 1871, pp.78 -117, especially p. 102; … Continue reading

The “panic” attributed to the French cavalry was probably no more than their retiring so that they would not come under friendly fire from their own infantry who they were masking. One should expect some bias from each side when reading so called eye witness accounts of what took place during the battle. Whatever the actual circumstances , the French were certainly forced to retreat, and in some disorder at that, scampering back to the protection of their gun line, which Balthus had now extended from Straden to Kulm containing and 24 cannon, their fire now adding to the boil of smoke coming from other batteries that Vandamme was establishing further to the left. [50]General Sir Robert Wilson who was attached to the allied army as an observer noted, ‘The lancers and dragoons of the guard charged through garden – ground and ravines [sic] upon the right column … Continue reading