9th – 10th March 1814.

Write your father a letter and urge him to be a little bit on our side and not to listen solely to the Russians and the English. [1]Napoleon to Marie Louise 1814

Despite the appalling losses suffered by his forces at the battle of Craonne (7th March), Napoleon was still convinced that Blücher’s Army of Silesia was retreating north in great disorder, and that if he could now follow it up and push it back well beyond Laon he would then be able to garrison that place and also re – fortify Soissons, which would help safeguard the route to Paris; thereafter he could turn his attention to dealing with the Allied Grand Army under the command of the dithering and doubt plagued Austrian, Prince Schwarzenberg.

For his part Blücher was criticised by his Russian allies for fighting at Craonne in the first place, particularly since it was they who had borne the brunt of the fighting while the Prussians did little to assist. To add to the problem Blücher was becoming increasingly unwell. This factor caused him to put aside any thought of a complicated battle plan to defeat the French and just sit tight on the defensive around the prominent hilltop town of Laon and let Napoleon waste his army in trying to push him back.

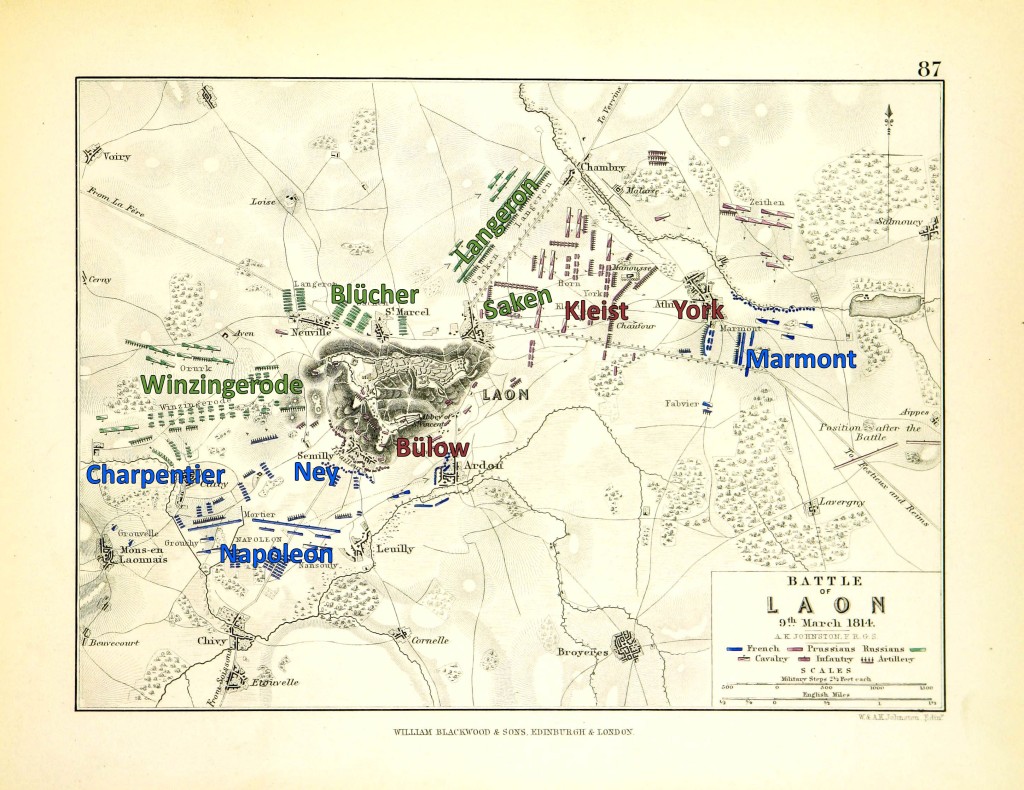

The French emperor, showing his usual trait of underestimating his opponent, planned a two pronged attack against what he considered was no more than a rearguard holding Laon. With the main body of his army of some 25,000 men consisting of the corps of Ney, Mortier and Charpentier, who was temporarily commanding Marshal Victor’s corps after the latter was wounded at Craonne, Napoleon would advance along the Soissons road for a direct drive on Laon. Marshal Marmont, with his corps of 9,000 men posted around Berry – au – Bac would advance along the Rheims road towards the village of Festieux, striking the enemy’s left around Athies. The problem with Napoleon’s plan was that Marmont’s corps was far away from the main body of the French army and the ground between (almost 3 kilometres) was covered in marsh land and dense willow groves thus making communication for a coordinated attack difficult.

Far from a weak rearguard awaiting the French onslaught, Blücher now had his whole army of close to 100,000 men deployed around Laon, with artillery covering the approaches from Soissons and Rheims, as well as strong garrisons holding the suburbs of Ardon and Sémilly, just to the south of the town. Wintzingerode, with the main body of the allied cavalry was to the west of the town, Yorck and Kleist’s corps on the east. Drawn up in reserve to the north were Langeron and Sacken with Bülow’s and Woronzoff’s troops in and around Laon.

In the early hours of the morning of the 9th March Marshal Ney began his advance against the villages of Chivy and Étouvelles, while General Baron Gourgaud, with two battalions of grenadiers of the Old Guard and 300 cavalry having already made a night march on the village of Chailvet from where they would join Ney in a proposed turning movement around the allied right flank. The atrocious state of the roads, plus a fresh fall of snow caused Gourgaud’s force to be delayed and as a consequence, at about 2.00 a.m., the brave but impetuous Ney, with 400 infantry from the ‘Spanish Brigade’, commanded General of Division Pierre Franҫois Joseph Boyer, stormed ahead of the main body of his corps, capturing the surprised Russian outpost in Étouvelles but encountered strong opposition at Chivy, before finally managing, as more French troops arrived, to dislodge the defenders and force them back towards Laon.

At 5.30 a.m., after finally getting his infantry and cavalry into position Gourgaud, despite a thick mist rising from the Ardon marshes, pushed on towards Semilly, to be greeted by rolling musket fire from an enemy that was now completely aroused. However Napoleon, back at Chavignon, was still convinced that he only had a rearguard to deal with and ordered the attack to be pressed, with Mortiers corps now beginning to bolster Ney’s line, but over on the right Marmont, after a stubborn fight with one of Yorck’s divisions around Athies, now halted until the mist had cleared.

At 11.00 a.m. the fog finally lifted revealing Yorck and Kleist’s masses to Marmont’s front, with the massive reserve of Sacken and Langeron’s corps backing them. He also became aware of a large body of enemy cavalry who would threaten his right if any forward move were undertaken. Realizing that to press on would result in his force being overwhelmed, Marmont decided to halt.

The clearing fog had revealed to Blücher who, because of his illness was now watching the battle propped up in a chair on the ramparts of Laon, just how weak the forces opposed to him were and as a consequence he ordered Woronzoff to retake Semilly, while Bülow’s troops also attacking the Ardon suburb. Coupled with these attacks Winzingerode would move his cavalry to threaten the French left.

Ney’s ragged and foot sore troops, totally overwhelmed and outnumbered, were driven back in great confusion, being saved only by the arrival of the French cavalry reserve and the Guard cavalry who drove the enemy back towards Laon. At 4.00 p.m. Napoleon had been informed that Marmont was around Athies and considered this to be the precursor of the plan he had prepared. Therefore he now ordered the Imperial Guard to attack Ardon and the Laon suburbs once more, their momentum causing the enemy to retire at all points with the exception of Semilly which remained firmly in their hands. The onset of darkness put an end to hostilities.

The ferocity of the French attacks plus the dispositions of their forces had bewildered Blücher at first, but once he realised that Napoleon had divided his army and that there were no enemy troops connecting each isolated wing he soon issued orders that would defeat Marmont’s corps before any aid could arrive from Napoleon.

After sending a force of 600 infantry and 400 cavalry under Colonel Fabvier to make contact with Napoleon’s main force and leaving the remainder of his troops to bed down for the night in the snow, Marmont retired to comfortable accommodation in Eppes, without bothering to make certain that, with the enemy in close proximity around Athies mill and the Mannoise farmstead, pickets had been posted and his subordinate commanders on the alert. His artillery was also in no position to assist if the enemy should attack, being parked unlimbered to the south of Athies. The small detachment of cavalry attached to Marmont’s corps under General Bordessoulle were not used for outpost duty but, like their comrades in the infantry, were more intent on warming themselves around their camp fires as the temperature had plummeted and it was freezing hard.

Complacently either cooking food or gathering firewood Marmont’s men were suddenly overwhelmed by compact masses of Prussian infantry appearing out of the icy darkness. Seized by panic almost 2,000 surrendered on the spot while the rest took to their heels abandoning 120 wagons and 45 cannon. Dashing back as soon as news of the disaster reached him, Mormont tried to restore some order among his wide eyed and breathless troops, but as soon as a ragged defensive line was brought together in an attempt to stem the rout it fell apart under the constant pressure of the enemy’s foot, horse and cannon.

The morning of the 10th of March dawned cold and grey with Napoleon, who was totally unaware of the disaster that had befallen Marmont’s command, still under the impression that Blücher was retreating back to Avesnes. Upon receiving new of the defeat he suddenly changed his mind and now, acting as if he had known all along that the old Prussian was in front of him in some strength, he considered that to have attacked Marmont Blücher must have weakened his right and centre and therefore if the French now held their position in front of Laon this would cause him to either abandon the town or bring back the troops pursuing his defeated lieutenant; a plan that even the most generous of Napoleon’s supporters would have to admit is the concoction of a man who had obviously lost touch with reality.

With a shaking voice, late on the evening of the 9th Blücher, upon hearing the news that Marmont’s corps had been soundly defeated, issued orders for the following day. While Bülow and Winzingerode held fast to their present positions, Yorck and Kleist would follow up Marmont’s fugitives back to Barry – au – Bac, while Sacken moved into the void created in the centre by Napoleon’s faulty dispositions and cut the Soissons road. This plan would have sealed the fate of both the French army and its tottering Emperor.

Unfortunately Blücher’s illness deteriorated still further and, as Baron Müffling states when visiting the old hussar at his headquarters on the morning of the 10th March, “…a large ante – room was quite filled up with officers. Among them I observed many Russian generals…and those old croakers who are to be found at all headquarters when great events frighten them.’ It was now that Müffling was informed that all forward moves had now been cancelled since Blücher was convinced that he was dying and refused to give any orders or take any more responsibility. The consternation caused was such that, although Langeron was the next senior general, he was fully aware that he was not capable of taking on the mantel of commander in chief. His obvious panic at having to possibly take charge caused him to state, ‘For God’s sake, whatever happens let us take that corpse along with us.’

Amidst the confusion Blücher’s Chief – of –Staff, General Gneisenau, who was no mean strategist, but lacked the strong will and charisma that Blücher exerted to bolster troop morale and, more importantly, keep a firm grip over his subordinate commanders who were not averse to causing problems owing to their own petty jealousies and ambitions, had taken it upon himself to cancel all the orders for the proposed attack, a decision that undoubtedly saved Napoleon from annihilation. The new orders issued instructed Langeron and Sacken to stand on the defensive until the French showed their intentions. Kleist and Yorck would halt their pursuit of Marmont, while Bülow and Winzingerode would be prepared to blunt any attack made on Laon.

The fighting on the 10th March was concentrated mainly around the suburb of Clacy, held by Charpenties’s corps, which Woronzoff endeavoured to take but was forced back by artillery and musket fire. Likewise, any forward movements by the French were also kept in check by the massed batteries of allied artillery around Laon. At 2.00 p.m. Woronzoff received reinforcements from Büow’s corps and Napoleon, once more under the impression that the enemy were about to retreat, ordered Ney to clear Semilly, Mortier to attack Ardon and Charpentier to advance from Clacy and storm Laon. All of these aggressive movement met with failure and, at 4.00 p.m., reluctantly, Napoleon ordered a retreat to Soissons. Gneisenau ordered a half hearted attempt to follow up the French on the morning of the 11th March, which was driven off by Ney commanding the rearguard.

The two day battle had cost the French 6,000 casualties, the Allies had lost some 4,000, but their losses could be replaced, Napoleon had scraped the barrel almost clean with no hope of retrieving either the manpower or the materiel left on the frozen fields of Craonne and Laon.

Laon Today

Graham J.Morris

October 2015

9

References

| ↑1 | Napoleon to Marie Louise 1814 |

|---|

Just read this fascinating account of the Battle of Leon and after visiting the town this morning and driving around the area once can see how Graham Morris’ description conjures up the various escarpments and battle situations very well (having reas about some of the sasme generals and characters at the Waterloo Museum a few days before this brings the time very much to life. What a brave, but desperate and difficult life soldiers must have led then.

Many thanks for your comments concerning Laon John.

Dr Bob and I had a very pleasurable visit to the battlefields of Craonne and Laon. The fact that the French army was able to keep going in 1814 after the disasters of the 1813 campaign had as much to do with its resilience as well as Napoleon’s fanatical determination to fight on regardless.

Thanks once again for visiting the site.

Graham J.Morris