Buried in the Snow: The Myth of Murat’s Cavalry Charge at the Battle of Eylau, 8th February 1807.

“ The most difficult task that can be imposed upon an army is to enter on a second campaign, against fresh enemies, immediately after one in which its moral energies have been partially consumed. Fortunate as Napoleon’s operations against the Prussians and Saxons in the autumn of 1806 had been, they all the same came to a standstill when, in winter, he encountered the Russians and the corps of General Lestocq, which had not previously been in action.”

General von der Goltz (The Nation in Arms)

Introduction

The military historian, Dr David Chandler wrote:

‘None of the great Napoleonic struggles is surrounded with more doubt and uncertainty than the battle of Eylau. Fact, myth and propaganda are almost inextricably intertwined, and different authorities give conflicting interpretations of almost every stage of the struggle’. [1]Chandler. David, The Campaigns of Napoleon, page 535.

Much of the myth has come down to us in the form of eye-washing by nineteenth- century battle painters and brainwashing by some military historians who, even up to the present day, consider that men, horses, artillery and wagons can go dashing around a battlefield covered by almost a meter of snow, in temperatures of –16c while intermittent blizzards raged.

Trying to piece together the individual events of this great battle is rather like attempting to unravel a tangled fishing line, just when you think you have found the correct loop to pass it through the whole lot gets even more entwined. Dealing with the battle as a whole, therefore, is not the object of this paper, but by focusing on our attention on one of the grand moments during its course, in this instance, Murat’s massive cavalry charge, we may come to understand just how complex, and at times how fabricated, a Napoleonic battle could be.

I do not intend to go into any great details of the campaign as a whole leading up to the battle of Eylau other than to mention events just prior to the battle which may have had an effect on the circumstances which occurred during its course; suffice to say that, like the battle itself, many other events that took place during this campaign are equally subject to doubt and conjecture.

The French Cavalry

After the defeat of the much- vaunted Prussian Army at the battles of Jena and Auerstadt (14th October 1806), Napoleon was able to replenish his cavalry horses at Prussian expense, and established a large depot at Potsdam. Here, and throughout Prussian conquered territory he was able to raise some 44,555 horse. These, together with the mounts that had not been worn out or killed during the previous campaign, gave the French a total of 60,000 comparatively fresh horses. [2]See, Petre. F. Loraine, Napoleon’s Campaign in Poland 1806 – 1807, page 26. Also, Rodgers. Colonel H.C.B., Napoleon’s Army, page 35 – 52. Petre also quotes from Marbot who, if he is to be … Continue reading It must also be remembered that a constant flow of horses were always being supplied to the French army from depots in France, as well as captured re –mounts and draught horses either requisitioned or just stolen during a campaign in enemy territory. The overall total amount of horses that were supplied to the cavalry is impossible to calculate; the various specialized units such as light and heavy cavalry regiments would each require different types of horses to fit their needs, and we must also not forget that the French artillery required over 5,000 horses to pull their guns, limbers and ammunition wagons, as well as field forges, forage and food wagons. There are also the mounts for generals, staff officers, regimental commanders and ADC’s to be considered, these might number somewhere in the region of 1,500 – 2,000, depending on how many spare horses each officer could afford.

Most sources agree that Murat assembled over 10,000 cavalry for his attack at Eylau, these consisted of:

- 2nd Division of Cuirassiers, 1,900 men (and horses?)

- 1st Division of Dragoons, 2,000 men (and horses?)

- 2nd Division of Dragoons, 2,200 men (and horses?)

- 3rd Division of Dragoons, 1,500 men (and horses?)

- Imperial Guard Cavalry, 1,500 men (and horses?)

The above gives us a total of 10,700 men. The reason for the parenthesised question concerning the horses is due to the fact that during the week preceding the battle of Eylau the French cavalry had been involved in a number of engagements as well as having to manoeuvre in conditions which would have caused many of their mounts to become unserviceable. I cite here a few examples of how combats and day to day marches and exertions do not tally with the estimates given for the cavalry force Murat led at Eylau.

On the 4th February Murat’s troopers were involved in a running fight with the Russian rearguard and at Deppen he led a charge which drove the enemy back. (Petre, page 154). On the 5th the reserve cavalry was engaged again in an attempt to slow the Russian withdrawal (Petre, page 155). Thereafter Murat pushed on ‘reconnoitring towards Liebstadt and Wolfsdorf, attacking the enemy with his main body should he find them in position’ (Petre, page 155) On the 6th the heavy cavalry were engaged with the Russians at Hof, ‘Murat leading the dragoons he had with him and followed by d’Hautpoult’s cuirassiers, hurried across the bridge (in front of Hof). There formation was constricted by a narrow defile, the dragoons were overwhelmed, before they could reform beyond it, by the onslaught of Russian Hussars and Cossacks, and were carried back in some confusion across the bridge’ (Petre, page 157- 158). [3]See also Morris G. J. More about Eylau, Monograph in Battlefield Anomalies. Since no information is thus far forthcoming on the strengths of individual units involved in the advance towards Hof, then we must rely on the figures given in Murat’s Corr.II, 302 of the French Archives, in which he gives a figure of 9,200 for the combined Divisions of Beaumont, Kline, Becker, Milhaud and Nansouty. Beaumont and Becker’s Dragoon Divisions Savary respectively, while Grouchy’s Dragoon Division had been recalled from Ney to join Murat. General Nansouty seems to have disappeared into the ether as neither Petre or Esposito and Elting in their work, A Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars, mention him again, indeed, Petre, although mentioning his name in the text does not even give him a credit in his index, and therefore we may consider only the Cuirassier Division of General d’ Hautpoult.

Not knowing the exact numbers of French dragoons at Hof, we have to come to the conclusion that only one division was present, say 2,000 troopers, but since during this period this type of cavalry also fought on foot, they may not have all been included in the correspondence because they fought dismounted?

The numbers of the French cuirassiers engaged at Hof also remains speculative, though the figure of between 1,000 and 1,200 seems to me to be a fair estimate, once again allowing for losses incurred on the march and in previous engagements. Only three cuirassier regiments fought at Hof, 1st, 5th and 10th; the 11th Regiment was not engaged, but may have been held back as a result of lack of horses, and/or mounts being too worn down by illness. Here it is worth considering the ailments horses are prone to when subjected to the conditions that prevailed during this campaign.

Having consulted various veterinarians and cavalry experts, I herewith give a brief list of some of the ailments to which horses are prone:

- Bruised soles: The area on the sole of the hoof especially the toe callus, around the white line, or even on the hoof wall and around the coronet band. This can occur when removing horseshoes.

- Horse Thrush: Fungal infection around the frogs and heel bulb, which can attack the tissue at the back of the hoof. Correct feeding is very important.

- Mud Fever/Cracked Heel: Occurs mainly in winter and early spring. Affects the lower leg and causes lameness.

- Laminitis: Inflammation of the lamina in the hoof (front hooves more commonly affected) so that it is unable to bear any weight on its feet. This can be life threatening.

- Ringworm: Fungal infection of the skin that can be spread by direct or indirect contact. Strict hygiene is essential.

- Rain Scald: Caused by the softening of the skin following prolonged exposure to saturation from rain or snow.

- Common Cold: Horses that are kept in close proximity with other horses from different areas of the country.

- Colic: Abdominal pain, possibly gut or other organ within the abdomen. Caused by a number of factors including bad diet.

- Saddle Sores: Chaffing caused by ill-fitting or incorrectly adjusted saddles and fittings.

- Collar Chaffing (draught horses): Caused by wet or split horse collars worn over a long period.

Taking the above into consideration then under the awful conditions that men and horses were subjected prior to and during the course of the battle of Eylau I consider that, with roads, (never very good in East Prussia during this period even in summer) frozen solid, thick snow covering the whole landscape and provisions lacking, then manoeuvring large groups of horsemen and forming regular battle formations would cause normal deployment and tactics questionable.

To return to the action at Hof, I can find no details of the French cavalry losses, but considering the severity of the weather and the fact that the losses given by Marshal Soult for his corps (also engaged at Hof) were 1,960 then a conservative estimate would be 150 – 200 men and horses. There is also another consideration to take into account here, the fact no army or portion thereof would attack an enemy in a prepared position without artillery support, therefore we have to consider whether, because of the appalling state of the roads, many of the French cavalry horses were used to double the teams of the artillery in order to haul the guns and limbers to the battlefield? When reading the, albeit at times conflicting accounts of this campaign, then we must constantly bear in mind the intense labour required to bring these necessities of war, and its ancillary equipment, to the right place at the right time; it is therefore quite possible that many of the French heavy cavalry horses (being stronger) were used to double the teams in order to pull the guns, limbers and wagons?

Another argument against the number of cavalry involved in Murat’s charge comes from an examination of individual regiments, both light and heavy, that were on the field at Eylau. As an example I will use General Lasalle’s Light Cavalry Division.

Lasalle’s division covered the French left flank and contained the brigades of Colbert, Guyot, Dorosnel and Bruyère. Although the exact figures for these units will never be known precisely, we can still arrive at a rough estimate of their strengths. The combined division was made up from the following:

Brigade Colbert:

- 10th Chasseurs à Cheval (4 squadron?)

- 9th Hussars (4 squadrons?)

Brigade Guyot:

- 8th Hussar Regiment. (4 squadrons?)

- 16th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment (4 squadrons?)

- 22nd Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment (4 squadrons?)

Brigade Durosnel:

- 7th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment (4 squadrons?)

- 20th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment (4 squadrons?)

Brigade Bruyère:

- 1st Hussar Regiment (4 squadrons?)

- 13th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment (4 squadrons?) [4]There are conflicting lists in regard to regiments and squadrons in the various French cavalry divisions. I have chosen what I consider to be the correct regimental grouping for each brigade.

If we allow for an average strength of 80 men and horses per squadron and 4 squadrons to each regiment then we arrive at the figure of 2,560 for the combined strength of this division. This will enable us to use a rough rule of thumb in determining the strengths of other units on the field.

Next we have to consider the Guard cavalry whom Murat includes in his total figures for the charge. These troopers would not have constituted the whole of the Imperial Guard cavalry, as we may be sure that Napoleon would have kept one or two “duty squadrons” of his Guard Chasseurs à Cheval with him in the event of a misfortune. The main units of the Guard involved were the Grenadiers à Cheval, these numbered six squadrons. As these were élite troops then we can say that they would have been kept up to strength, even to the detriment of other units, and so we should put a figure of 100 – 150 men and horses per squadron, giving them 600 – 800 engaged. The Guard Chasseurs à Cheval numbered five squadrons, but whether or not these took part in the charge is debatable; therefore we should allow a conservative estimate of between 300-400 for this formation.

As we have seen, the dragoon and cuirassier divisions suffered losses during the advance and engagement at Hof, and they most probably also incurred a substantial loss of horses in each unit owing to the lack of forage and general hardship of campaigning in difficult conditions (just how they were re-shod under these conditions would make an interesting paper in itself). This being said therefore if we allow the same number per squadron for each regiment in each brigade and division as we gave to the light cavalry under Lasalle, we arrive at the following:

Klien’s Dragoon Division.

Brigade Fenerolz:

- 1st Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

- 2nd Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

Brigade La Motte/ Fauconnet:

- 4th Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

- 14th Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

Grouchy Dragoon Division

Brigade Bron:

- 3rd Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

- 6th Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

Brigade Milet:

- 10th Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

- 11th Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

Milhaud Dragoon Division

Brigade Boye:

- 5th Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

- 12th Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

Brigade Marisy:

- 8th Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

- 16th Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

Brigade Maupetit:

- 9th Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

- 21st Dragoon Regiment (4 squadrons?)

d’Hautpoul Cuirassier Division

Brigade Saint- Sulpice:

- 10th Cuirassier Regiment (4 squadrons?)

- 11th Cuirassier Regiment (4 squadrons?)

Brigade Clément:

- 1st Cuirassier Regiment (4 squadrons?)

- 5th Cuirassier Regiment (4 squadrons?)

Once again, if we now allow 80 men and horses for each squadron, then we arrive at a figure of 7,280 for the combined Dragoon and Cuirassier divisions. If we now add the Guard cavalry to this total and also add the Guard Chasseurs à Cheval contributing one or two squadrons to the charge, then we arrive at an overall count of approximately 8,300. Next we must take off the numbers killed and wounded during the engagement at Hof, and also, and this is a crucial factor in my opinion, the loss of horses and reallocation of same to other tasks, as well as those unfit for duty from pure exhaustion, say 600 – 800. This now leaves us with no more than 7,000 – 7,500 men and horses engaged, a far cry from the 10,700 quoted in most sources. Of course the latter number was estimated on the “full” squadron strengths, and not on how these strengths had been eroded during the course of the campaign.

The Russian Army

The formation of the Russian army at the commencement of the battle tells us a great deal about how it manoeuvred on the battlefield. Much criticism has been levelled at Benningsen’s deployment of his forces, but there may have been a good reason for him choosing to concentrate his army in the way he did. Petre, quoting from Jomini, Hoepfner and others, states that the Russians were ‘…standing out when the atmosphere was clear, in sharp relief against the white snow on the bare slope, without any cover whatever, were exposed from head to foot to the fire of the French guns.’ [5]Peter. F Loraine, Napoleon’s Campaign in Poland 1806-1807, page 179. By forming his units up in compact masses Benningsen could well have been taking the state of the ground into consideration. When we remember that the snow was several feet deep, then to move companies and battalions in linear formations would have caused the ranks to become disordered and distorted while stumbling through heavy snow drifts, likewise the same for the cavalry: whereas solid columns would be able to move rather like a snow plough enabling them to keep some form of alignment. The argument that the Russians must have formed lines otherwise Murat’s charge could not have been said to have broken through “several” of these during its course depends on ones idea of how these lines were made up. I can find no firm source that mentions the Russians forming squares during the French cavalry attack, normally the only way of receiving such a threat without disaster. What I consider happened was this – once again allowing for the state of the ground – each regiment/battalion, in column formation, faced their flank files outwards and their rear rank(s) back, thus presenting a solid mass of bayonets. [6]The Austrian infantry used a similar tactic. The soldiers who had become disordered or wounded during the advance from their main position (and these may have numbered several hundred?) simply lay on the ground allowing the French cavalry to pass over them while lunging upwards with their bayonets and causing much damage to the poor horses. Some strong evidence that the Russian infantry prostrated themselves in the snow comes from several sources ( although not directly related to the battle), and the fact that they rose up again and faced to the rear as the French retired seems to suggest that it may have been a planned action which allowed for certain conditions of the ground and weather, plus the fact that the attacking cavalry could not employ their normal formations? [7]The Russian soldiers were given the nickname, “Resurrection Men” during the Crimean War for employing just such a tactic, also John Keegan in his work, The Face of Battle, quoting from a trooper … Continue reading

There is no mention of the capture of any Russian artillery pieces, nothing regarding rendering them useless by driving nails into the vents or breaking the sponge staves so that the cannon could not be swabbed out; no standards appear to have been taken, and very few, if any, prisoners taken. Napoleon himself was not convinced that the charge had done anything other than stall the Russians and he certainly did not expect to exploit its effects by sending in the Imperial Guard foot regiments to complete a victory. It was, in fact, nothing more than a desperate throw by a desperate man who had insufficient resources on the field, and treated his enemy with contempt. The “Great Cavalry Walk” should be seen as part of a battle in which both sides were, in all probability, performing in slow motion. The high death toll on both sides seems to indicate a bloody fight to the finish, but in reality most of those reported as killed probably died from the cold and sheer exhaustion. The expression, “To lie like a bulletin,” probably derived, not from Napoleon wishing to play down the real numbers of his soldiers who were killed in action, but to cover up his own failure in not supplying them with adequate food and clothing before entering upon a campaign for which he, and his army, was totally unprepared.

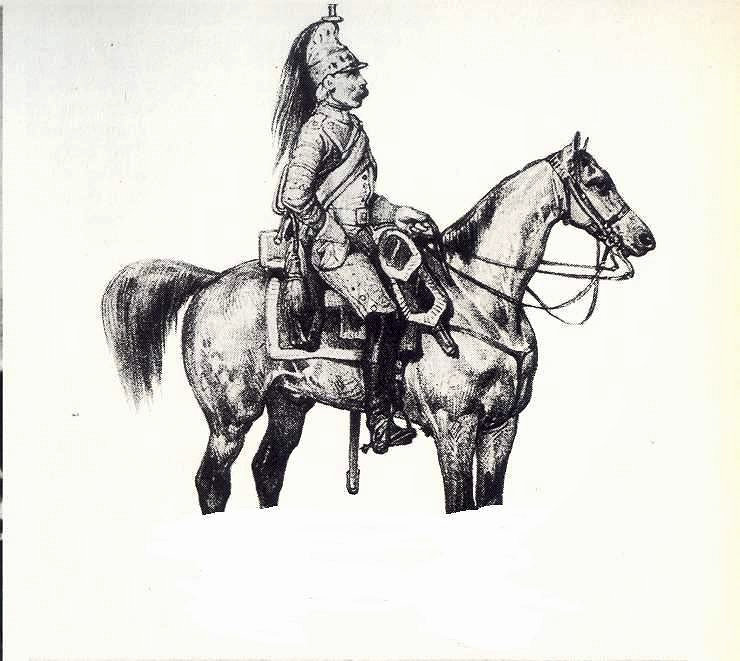

The Men and the Horses

The average dragoon trooper carried approximately 10 kilos of equipment on his person, these included helmet, uniform, sword and scabbard, cartridge-pouch with 10 – 20 cartridges, sheep skin or deer hide breeches or linen overalls, knee-high leather boots with a woollen insert around the knee to prevent rubbing, cross belts and sword belt; he would also have worn whatever he could during the severe winter underneath his tunic for more warmth. The cuirassier uniform was much the same as the dragoon, with the exception of them wearing the front and back cuirass from which they took their name; these items added a further 8 kilos to the wearer, when straps and fixings were added.

As well as the above equipment, each trooper had the following: a saddle of leather with bridle and stirrups, a black leather crupper, martingale, leather pistol or musket holder, portmanteau with straps that held a cloak or cape on top, sheepskin half – shabraque or saddlecloth with holster covers, stable and parade halters and pistols or a musket. Any additions to the trooper’s comforts, as well as the need to carry rations minimal for himself and his charger would increase the burden of the horse.

The problem of shoeing horses under the conditions that prevailed in the weeks leading up to the battle of Eylau has been alluded to before in this article, but it is worth considering other aspects of this problem when dealing with the battle itself. I quote here an extract from Colonel Girois, who commanded the artillery of the 3rd French Cavalry Corps in the 1812 Russian campaign as an example:

‘We now encountered a new difficulty: the slippery surface of the hardened snow offered no purchase to the horse’s feet. We had reserves of ice-nails all right, but we had not used them for shoeing the horses. Even this would not have sufficed, because after several hours march their diamond-sharp heads were worn and they became absolutely useless, we had discovered later. Iron crampons are much better, but we should have needed more time and resources than we had to shoe our horses in this way.’ [8]Quoted in: Brett-James. Antony, 1812 Napoleon’s Defeat in Russia, page 220.

Not only the fact of the horses needing such things as ice-nails and crampons should be taken into account when dealing with the Polish campaign of 1807, but also the method by which these were supplied, if at all, and how they were transported. For all the horses of the cavalry and artillery, plus ancillary support wagons and officers mounts, the French army would have required approximately 500,000 ice-nails and crampons. These in turn would require 50 field forges working flat-out at shoeing 50 horses each per day for a week, a prospect I find hard to accept, therefore I consider that most of the French cavalry on the field of Eylau remained with normal horseshoes, together with all the hardship that this entailed. [9]*See Appendix I.

The Myth and the Glory

With all of the above being said then such armchair prose as – ‘At any other season the marshy country around Eylau would have made deployment difficult, but in February 1807 the bitter East Prussian winter was at its height. Lakes and streams were all covered by thick ice, and everything lay under three feet of snow. The battlefield was a vast white landscape, on which massed cavalry might charge full out.’ [10]Johnson. David, Napoleon’s Cavalry and its Leaders, page 53. – are pure nonsense, and are typical of writers who have probably never walked through a meter of snow (waist high), never mind “charging full out” over a battlefield covered in the stuff! Other examples of this type are all too easy to find, ‘ General Grouchy’s dragoons charged [sic] first, to sweep the ground and clear it of enemy cavalry,’ [11]Thiers. L.A, History of the Consulate and Empire of France under Napoleon, Vol. IV, page 429. and ‘ in marvellous fettle [sic] 80 squadrons of splendidly accoutred horsemen [sic] swept forward.’ [12]Chandler. David, The Campaigns of Napoleon, page 543-544. There are many more like these which I am sure the reader has been inspired by in imagining the panoply of battle; the truth however is that what we see in films, and what the war gamer can do with his uncomplaining miniature armies on a tabletop is very different from what takes place during a real battle. Even the most diligent and painstaking military historians can succumb to flowery prose, especially when writing a work that will appeal to the general reader as well as the academic, in many cases there are just causes for some elaboration, but if we wish to find the truth then we must cut away the flowers and get down to the roots.

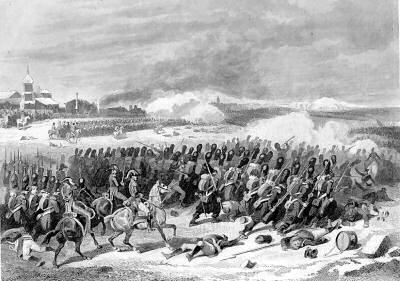

If the military historian can manipulate our way of thinking then how much more so the military artist? Nineteenth century battle painters, although producing some uplifting scenes of military glory did, by and large, apply too much artistic licence to many of their works. The splendid craftsmanship of the French painter Edouard Detaille will forever be associated with the Napoleonic legend, but even his meticulous brushwork covers the truth with a veneer of glorious improbabilities. The fact that he used the same composition on at least two paintings, one of the French Guard cavalry at Eylau, the other of French Carabiniers during the campaign of 1812, should make us wary of historical data. In the painting of the French Guard Grenadiers à Cheval at Eylau, Detaille shows the stalwart Grenadiers receiving Russian canon fire in firm ranks wearing only their tunics, with their cloaks still rolled on their portmanteaus. They stand in a few centimetres of snow while their commander, Colonel Lepic, tells his troopers to hold their heads up, stating that they are being assailed by cannonballs not turds. [13]This is reported in several sources, none of which give any information about who over herd Lepic make this statement or if he reported what he said later? All of this is, of course, very heroic stuff (or is it, when the cream of the French army appear to be afraid of being killed?), but we must not forget that it aims to show the glory of French arms, and was painted not long after France had been defeated, somewhat humiliatingly, during the Franco- Prussian War of 1870 – 1871, and therefore needed some kind of uplifting experience. The other problem with this painting comes from the interpretation we give to just what Colonel Lepic actually was saying, and indeed if it was at all possible for his men to hear him anyway, with a howling wind blowing and his back turned to most of them. Also, it may have been that the grenadiers were not lowering their heads to avoid Russian cannonballs, but merely hidings their faces from the cutting effect of the wind and driving snow stinging their eyeballs!

Another painter who puts his skills to good use in the form of artistic propaganda is L. Flameng, whom even David Chandler considers to give ‘A romantic reconstruction of Murat’s charge.’ [14]Chandler. David, The Campaigns of Napoleon, page 246-247. In this epic battle painting Flameng depicts Murat at the head of the French cuirassiers, dressed in Russian Boyar type garb, wielding a riding whip and mounted on a rearing horse. We see tails, manes and horse-tailed plumed helmets flapping in the wind, whereas, in fact, this whole hairy mass would have been, if not frozen stiff, then certainly not capable of this type of movement. Once again we see the French cavalry without the protection of their cloaks, while their Russian adversaries, many of whom look like old age pensioners, stand in huddled amazement in their greatcoats awaiting their fate. As with Detaille, we are presented with an image of French cavalry greatness; mounted on what appear to be prime racehorses, they are seen “charging full out” in a few centimetres of snow with no apparent effects from the appalling conditions under which they had spent the previous night, but rather as if they had just taken part in a full dress parade.

The work of another military artist, F.Schommer, also shows the French Guard Grenadiers à Cheval charging [sic] into battle, once again they are dressed for a walk in the park, and once again they dash across a sprinkling of snow, much of which seems to have collected more on their bearskin bonnets than on the ground. The officers are well out in front and mounted on horses that once more look like well fed and groomed thoroughbreds.

It really is a shame that we have allowed ourselves to be hoodwinked by this type of sham battlefield representation. The facts may not have been quite what the salons of Paris desired to put on their walls but, nevertheless, the use of rhetoric and flowing brush strokes should not try and sanitize the dirty, bloody truth of war.

The Weather

The cold had been intense for several days before the battle, and both Russian, French and Prussian forces must have suffered terribly as a result. Petre tells us that, ‘So firmly were they (the lakes and the streams) locked in the grasp of frost, and so completely concealed by the snow, that troops of all arms, horses, wagons, guns, passed over their frozen surface, without being aware that water lay beneath their feet,’ and again, ‘The gunners knew not there was ice; had they known it, it is by no means certain that they could have broken it through the three feet or more of snow protecting it from all but a plunging fire.’ [15]Petre. F. Loraine, Napoleon’s Campaign in Poland 1806 -1807, page 163-164.

*See Appendix II The latter statement creates yet another problem during the battle and for Murat’s charge, just how did the artillery of both sides manage to swab – out their cannon if all the water in the area was frozen solid? If they were reduced to melting snow in buckets, what prevented this from either freezing over once again or just causing the sponges to become brick – hard? We may be sure that it would have been impossible to have fires burning next to every battery to melt the snow, or indeed to keep the fires burning anyway, with constant snow storms causing blizzard conditions and a lack of dry wood. [16]See Appendix II

During the evening and night of the 7th-8th February 1807 the temperature dropped from – 5c down to a numbing – 16c. Under such conditions items such as clothing and other material when exposed to the frost becomes inflexible and stiffens as it begins to freeze, adding extra weight to the wearer. Swords become frozen to scabbards, while muskets and cartridges are difficult if not impossible to use to best effect, to say nothing of the hands that are required to perform the tasks of using them. That the frost was intense is verified by the French surgeon Larrey, who tells us that while performing operations on the battlefield, and inside a barn at that, the instruments fell from the attendant’s hands with the cold as they waited on the operating surgeons. [17]Petre. F. Loraine, Napoleon’s Campaign in Poland 1806-1807, page 173.

After the onset of a cold spell in December 1999 I left various articles of military and civilian equipment outside overnight in temperatures of between -4c-5c; there had been a light fall of snow but no more than 3 – 4 centimetres. The military articles consisted of a Grenadier Guard officer’s greatcoat and an old German Jager pack from the First World War. The straps on the pack although worn were nevertheless in reasonable condition and I treated them with saddle soap and leather protection spray. The greatcoat was in very good condition and I placed woollen material inside the sleeves to facilitate some form of warmth, nevertheless, the following morning, the straps on the pack had become almost impossible to unfasten, and only several minutes of working at them made them yield to my efforts, which were performed with reasonably warm hands. The greatcoat had become almost ridged, and considering that even with body heat being generated, which may have allowed more flexibility to the material, under the conditions that the soldiers on both sides had to endure at Eylau, unless they moved around all night, then these items of clothing must have become unbelievably stiff and inflexible.

The other items left outside were a pair of modern leather riding boots and an ancient 1860’s ball and cap shotgun, which has the same basic actions as the musket. The boots were also stuffed with wool and other fibres to keep in some warmth but these, like the leather straps on the pack, became almost rock – hard and extremely painful to move in when put on. The old shotgun had been well greased, and its firing mechanism was in good working order, however, even this did not prevent it from freezing around the trigger and firing plate, whilst the ramrod became welded into its bracket support under the barrel and need warm water to free it (some reports about rifles freezing due to bitter weather during the First World War on the Eastern Front mention soldiers urinating over their rifles in an attempt to unfreeze them).

The Charge

The preparation for Murat’s charge [sic] must have trodden the snow down greatly, and the movement of large bodies of infantry would also have reduced its original depth, however, snow does not disappear when ridden or walked through by thousands of men and horses, but rather remains deep in places and in others becomes so compacted that it turns into a veritable ice-rink, also the fact that the ground underneath the snow was iron hard from the severe frosts of previous days must have made movement treacherous. These factors must be taken into account when we consider the method of deployment employed by the French cavalry in their advance.

There is some proof of the way in which the French attacked which comes from, Souvenir de Capitain Parquin. Parquin tells us that, ‘Towards two o’clock in the afternoon an enormous mass of cavalry [Russian]was set in motion and advanced towards us at a walk; the snow and marshy [sic] ground not permitting any faster pace. [18] Parquin. C. Captain, Récits de guerre; souvenirs du capitaine Parquin, 1803 -1814, Quoted in Rogers… Colonel H.C.B. Napoleon’s Army, page 50. With such an eyewitness account we may therefore safely say that the conditions would be the same for the French as for the Russians and that when Murat led his squadrons forward he would have chosen a formation that took the state of the ground into consideration.

It is my opinion that the French cavalry adopted an en muraille formation in great depth. The en muraille [19]See appendix III deployment consisted of each regiment forming their squadrons in line immediately beside one another, there were no intervals between each squadron and they rode forward boot to boot.

The front of Murat’s column would therefore be 120 – 140 metres wide and, allowing for all the reserve cavalry and the Guard forming one behind the other in regimental squadron lines with only minimal space between each regiment, would be approximately 900 – 1,200 meters from the head of the column to its rear. Indeed, almost just such a formation is depicted by one of the more down to earth battle painters, Simeon Fort, in one of his Aquaraelle’s, La battaille d’Eylau (musée de Versailles).

Here we see that, given the conditions of the field, and just as importantly the condition of the men and horses, that Murat used his troopers like a battering ram or bulldozer to literally smash his way through the Russian lines. Now, if we also take into account the fact that trumpet calls would be difficult to communicate to each squadron over an extended distance owing to the wind, also officers orders would not be heard due to the same factor, then this type of tight grouping would have made control and command far more reliable. At a walking pace the French cavalry would not over-exert their already much fatigued mounts, and the fact that they were attacking Russian infantry and cavalry who were “masking” their own artillery as they were themselves advancing after the defeat of Augereau’s Corps meant that they only had to receive the fire from Russian muskets, and possibly not much of this either when we reflect on what the weather could do, not only to these weapons, but also to the cartridges, powder and hands that made them effective.

Petre (page 185) tells of the Russian cavalry ‘going down before the shock,’ and this could be taken quite literally when we picture the great mass of flesh and steel of the French juggernaut smashing aside anything that stood in its way, and the momentum and force of so many thousands pressing from behind would make this impact and pressure become greater. Petre also hints (page 185) at what the French cavalry formation was like when he writes, ‘this great line of cavalry, followed by others, poured in successive waves up the slope.’ And here we may well imagine the cuirassiers and dragoons, in their regimental squadron lines, coming on like an unstoppable tide. The “slope” Petre mentions would however cause another problem, as with the onset of sporadic blizzards any form of gradient and fold in the landscape would mean that the snow would be deeper in some places more so than in others, thus making any uphill progress difficult to negotiate.

The Debate Continues

I wrote most of the above monograph almost twenty years ago after watching Robert Ryan in the film ‘The Day of the Outlaw,’ a western in which horses are shown trying to walk through deep snow. Since then I have been contacted by some well respected historians, not to mention the dozens of good folk who have visited and discussed this particular subject on my website, and it really does seem that there is no end to just how much more we need to discover concerning the mythology surrounding Eylau – and thus the search goes on.

One historian in particular with whom I have had the brief pleasure of communicating is James R. Arnold. His very detailed account of the campaign, up to and including the battle of Eylau, Crisis in the Snow, (co-authored with Ralph Reinertsen) shoots many holes in the excepted accounts of the battle and also, although not completely, tallies with my own theories concerning the battle. Where we diverge is in dealing with the French army in comparison with the Russian. While agreeing with Arnold and Reinertsen on much of what they say about Napoleon’s over-zealous, underestimated, and ill considered decisions in continuing the war against a fresh opponent with winter fast approaching, they do tend to place too much emphasis on Russia’s part in what was, in fact, Napoleon’s own self created errors, with little to say with regard to Bennigsen’s equally pig-headed decision to squander the lives of his soldiers in a winter war in the bogs and snowdrifts of East Prussia.

Original published 2002,

updated 24 April 2018

Appendix I

Regarding the French cavalry horses, it should also be remembered that, because of the great weight they had to carry, the cuirassiers were normally mounted on Norman or Flemish horses, these however were heavy and slow, not being able to go at more than a trot after an hour or so in the field, even during fine weather and on firm ground. (Rogers, page 42.)

Colonel Griois, commanding the artillery of the 3rd Cavalry Corps, once again tells us about the difficulties faced by his horses attempting to move guns and wagons in snow during the 1812 Russian campaign. ‘Eventually we managed to tow all our vehicles out of the park, one by one, by means of doubling, even trebling the teams of horses. But it was quite impossible that four horses to each vehicle – we were obliged to reduce most of them to that number – could manage on the slippery tracks we had to move along.’ (Brett- James, page 221.) The conditions occurring during the days leading up to the battle of Eylau, as well as those on the battlefield itself, must have presented the same problems for the artillery of both sides.

Yet another eyewitness account, albeit once more in regard to the retreat from Moscow in 1812, but nevertheless still relevant to the state of the French horses in 1807, comes from English general Wilson, attached to the Russian army as an observer. On seeing several French horses lying on the ground his Cossack escort grew very excited stating ‘God has made Napoleon forget that there was a winter in our country…’ pointing to the fact that the dead animals were improperly shod with normal horseshoes. (Brett- James, page 223.)

Horses were surely the most essential and least appreciated un-sung heroes of war.

Appendix II

Wood was available in great quantities in East Prussia; the problem was that much of it in the winter of 1806-1807 was either green or wet. Pine trees were plentiful but do not give much heat when green and therefore smoulder and smoke a great deal rather than burn properly, giving off eye stinging fumes from the resin. Furniture from the houses in the surrounding villages would be the first to go up in flames, followed by doors, windows, roof timbers and anything else combustible. The Russians, retiring before the advancing French, would have probably carried off all they could manage, and thousands of men can manage a great deal. All warm coverings such as bed quilts, blankets, floor coverings and the like, would have been either, gathered up and taken into the forests by the villagers before the rampaging hordes descended or, if left on site, taken by the soldiers to wrap themselves in for protection against the cold.

How many men could a peasant cottage hold? Well, given the poverty that was prevalent, not only in East Prussia during this period, but in Europe in general then, although not being a hovel, the average cottage or house would not have had more than one or at most two bedrooms: a sitting room/ kitchen, outside night soil lavatory and maybe a washhouse with a pump (more than likely a communal village pump or wash fountain was used), and this would have been a family accommodation. Larger buildings would of course hold more men but other than a church or a local government structure these would not have amounted to very many in the small villages around the Eylau battlefield. The abodes of wealthy citizens offering more luxurious accommodation would have been commandeered for the top brass of the army. Barns would have been the ideal place to shelter but in the early nineteenth century these would have been quite small and capable of holding only a hundred or so men. This in itself once again causes even more problems with the human condition of having to urinate and defecate.

Given all the above then no more than a small percentage of both the French and Russian armies would have found shelter from the severe cold that prevailed during the night and day of 7th– 8th February 1807: many thousands would have had to make-do with outdoor bivouac conditions. These were rudimentary to say the least when engaged on a campaign of regular movement. Shelters were constructed from branches and canvas (the latter if available) tied together and the interior either covered with pine branches or, on rare occasions, straw. Fires were normally lit a few meters from the shelter but at Eylau most probably inside to protect them from the wind and snow and give some warmth to the occupants of the shelter. The artillery crews found some protection from the elements by sheltering under their caissons and wagons, but fires were out of the question unless lit at quite a distance owing to the close proximity of ammunition and powder.

Appendix III

The wind direction also proves another problem during the course of the battle. The Prussian General Lestocq, marching to the aid of the Russians at Eylau, was on the heights between Drangsitten and Graventien and could clearly see the flashes and smoke of the cannonade on the battlefield yet could not hear a sound. (Petre, page 195). Ney, seven miles north-west of the battlefield was also unaware of any gun-fire; also both sides claimed that the snow was blowing directly in their faces, reducing visibility to a few meters. This is what Summerville has to say:

‘…the two armies were drawn up in a line running north-west to north-east, this would suggest the wind was blowing either from the north-east (blowing into the French faces) or the south-west (blowing into the Russian faces). … Interestingly, Pierre Franҫois Percy, Napoleon’s senior doctor, talks of a “north wind” in his account of the battle. Needless to say, a northerly or north-westerly wind could not have blown snow in the soldiers faces: except, perhaps, those of Marshal Davout’s III Corps, toiling up the Bartenstein road. Did the wind change direction? We will never know.’ (Summerville, page 89)

During the American Civil War sound distortions like the ones described above were given the name, “Acoustic Shadows,” and it is very possible that, owing to the weather, just such an anomaly occurred during the battle of Eylau. However, there is also the possibility that, because of the damp and cold conditions, much of the ammunition and powder used by both sides had become useless causing many dud discharges from the cannons and producing no explosive charge but just fizzling out in a cloud of smoke?

Bibliography

| Bowden Bowden, Scott, | ‘Armies at Waterloo’. Empire Press, Arlington, 1983 |

| Bukhari Bukhari, Emir, | ‘Napoleons Cavalry’. Osprey Publishing, London, 1979 |

| Chandler Chandler, David, | ‘The Campaigns of Napoleon’. Weidenfield and Nicolson, London, 1966 |

| Esposito et al Esposito and Elthing, | ‘A Military Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars’. West Point, 1963 |

| Fuller Fuller, General J.F.C. | ‘The Decisive battles of the Western World’. Vol. II, London, 1963 |

| Brett-James Brett-James, Anthony, | ‘1812 Napoleons Defeat in Russia’. Macmillan, London, 1966 |

| Jomini Jomini, Baron Henri, | ‘Vie de Napoleon’. Paris 1827 |

| Johnson Johnson, David, | ‘Napoleons Cavalry and its Leaders’. Batsford Books, 1978 |

| Lachouque Lachouque, Henry, | ‘Napoleons Battles’. George Allen and Unwin, 1966 |

| Nosworthy Nosworthy, Brent, | ‘The Anatomy of Victory-Battle Tactics 1689-1763’. New York, 1990 |

| Petre Petre, F. Loraine, | ‘Napoleons Campaign in Poland 1806-1807’. Greenhill books, 1989 |

| Rogers Rogers, Colonel C.B. | ‘Napoleons Army’. London, 1974 |

| Thiers Thiers, Adolph, | ‘History of the Consulate and Empire’ Vol. IV. London, 1847 |

| Murat | Murat’s report from the, ‘Archives Historiques’. Quoted in [Petre]. List of Works Consulted. |

References

| ↑1 | Chandler. David, The Campaigns of Napoleon, page 535. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See, Petre. F. Loraine, Napoleon’s Campaign in Poland 1806 – 1807, page 26. Also, Rodgers. Colonel H.C.B., Napoleon’s Army, page 35 – 52. Petre also quotes from Marbot who, if he is to be belived, states that between 12 and 16 horses were required to pull a carridge through the Polish bogs and quagmires. Ibid, page 220. |

| ↑3 | See also Morris G. J. More about Eylau, Monograph in Battlefield Anomalies. |

| ↑4 | There are conflicting lists in regard to regiments and squadrons in the various French cavalry divisions. I have chosen what I consider to be the correct regimental grouping for each brigade. |

| ↑5 | Peter. F Loraine, Napoleon’s Campaign in Poland 1806-1807, page 179. |

| ↑6 | The Austrian infantry used a similar tactic. |

| ↑7 | The Russian soldiers were given the nickname, “Resurrection Men” during the Crimean War for employing just such a tactic, also John Keegan in his work, The Face of Battle, quoting from a trooper of the British 2nd Life Guards at Waterloo stated that the French infantry, ‘…threw themselves on the ground until we had gone over, then rose up and fired.’ Page 153. |

| ↑8 | Quoted in: Brett-James. Antony, 1812 Napoleon’s Defeat in Russia, page 220. |

| ↑9 | *See Appendix I. |

| ↑10 | Johnson. David, Napoleon’s Cavalry and its Leaders, page 53. |

| ↑11 | Thiers. L.A, History of the Consulate and Empire of France under Napoleon, Vol. IV, page 429. |

| ↑12 | Chandler. David, The Campaigns of Napoleon, page 543-544. |

| ↑13 | This is reported in several sources, none of which give any information about who over herd Lepic make this statement or if he reported what he said later? |

| ↑14 | Chandler. David, The Campaigns of Napoleon, page 246-247. |

| ↑15 | Petre. F. Loraine, Napoleon’s Campaign in Poland 1806 -1807, page 163-164.

*See Appendix II |

| ↑16 | See Appendix II |

| ↑17 | Petre. F. Loraine, Napoleon’s Campaign in Poland 1806-1807, page 173. |

| ↑18 | Parquin. C. Captain, Récits de guerre; souvenirs du capitaine Parquin, 1803 -1814, Quoted in Rogers… Colonel H.C.B. Napoleon’s Army, page 50. |

| ↑19 | See appendix III |

A friend of mine who moved to the East coast last year has sent me an email. Because he is working from home during lock-down he has a little extra time for reading. He informs me that after reading my comments on the conditions at Eylau and the present state of the weather over on his part of England, he cannot even get his car out never mind a horse!

Thanks Andy

Greetings Andrew!

Happy to know that you can download some of my articles-no problem with that, but please state source when quoting anything from this site if you need to reproduce some facts for exams or publication.

Graham J.Morris (battlefieldanomalies.com)

Greetings Andrew!

Happy to know that you can download some of my articles-no problem with that, but please state source when quoting anything from this site if you need to reproduce some facts for exams or publication.

Graham J.Morris (battlefieldanomalies.com)

Dear Sir, whilst I have no wish to disagree entirely with your careful and reasonable analysis I would point out that your three feet of snow foundation may be, and probably is, wrong. I live in a country which has sub zero temperatures for more than half the year. We also experience severe snowfall during this same period.

When the wind is blowing, snow never lies evenly. Ice does not form on the surface of deep snow during one nigh even in minus 40 degrees, so ice nails would not be needed and , indeed would only be a hindrance. Also, no soldier would leave the only means (plus luck) of surviving the horror of the impending battle exposed in the manner of your experiment. My last point: you made no reference whatever to de Marbot who was there, and who rode to the remains of the square of the 14th Infantry of the Line and brought away the Regimental Eagle, as the stood their ground and were wiped out.

Dear Chris,

Thank you for visiting the site and your interesting comments on my article concerning Eylau.

Although I appreciate what you say about the depth of snow on the field you must remember that most sources (coming from participants in the battle) state that there was indeed a meter of snow on the ground. As to the ice on snow then I do indeed have no reason to contradict you because your knowledge on this matter is greater than mine. However, I would take you to task on the subject of soldiers equipment and clothing. One only has to read (and see) what the German army suffered during a Russian winter in the Second World War, clothing frozen, weapons malfunctioning etc, etc, to get a good example of what it must have been like in 1808.

As for Marbot, well, he never told the truth when a lie would suffice!

Best wishes,

Graham

This is somewhat late reply but the one meter figure doesn’t sound very believable. Looking at the weather statistics https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11600-017-0007-z (Eylau is just on the Kalingrad side of the border), it seems mean snow cover depth for winter is about 10 cm and maximum during 1952-2013 period was approximately 60 cm. The participants could probably find places with one meter of snow as snow has a tendency to pile against obstacles, but the average snow depth on fields and lakes was probably much less.

Also, snow can be a bit… complex. Depending on weather earlier during that winter, few tens of centimeters of snow can be a hindrance or an advantage. Frozen ground or compacted snow aren’t usually slippery unless temperature is close to melting point, which it apparently wasn’t.

Thank you for your comments Marko.

The problem with comparing 1807 with now is that we only have the word of the participants to go by, and I can see no reason why they would all mention a metre of snow covering the battlefield if it was not the case? The winters were far worse in the 19th century than they are today, but even in 1947 in England, we had a severe winter in which, in some parts of the country, a meter of snow covered the ground.

Thanks for visiting the site!

Graham

Thanks to the fantastic illustrations in what we knew as “The Funcken Books”, I became, in my wargaming teens, a slavish worshipper at the shrine of Napoleonic French cavalry “Gloire”. I swallowed whole an article in “Tradition” about the great charge at Eylau. Two score years on, I have developed a scepticism about the official French account of Eylau. If French accounts of the charge are correct, we have the unique spectacle of an army fighting on despite having its centre smashed, and its left wing bent back (On what, if the centre had gone?), yet which still held the field at 10:00pm, and only moved off because its supply system had broken down. I am very much with you, and your analysis.I would go further, and say (uncontroversially) that french Cavalry in the Napoleonic wars wasn’t really that good. Anyone who disagrees may like to explain why the cavalry at Fuentes achieved considerably less against the allied right wing than the Cossacks did at Borodino in their attack on the Young Guard.

Dear Chris,

Thank you for visiting the site and your interesting comments concerning French cavalry.

Waterloo shows us a bad example of British cavalry control and command during an engagement, however, the French were equally as bad when one considers occasions such as the ones you mention, plus their poor performance overall during the Spanish campaigns.

Best wishes,

Graham J. Morris (Battlefield Anomalies)

Dear Graham,

I greatly appreciate your thoughtful attention to matters of weather and its impact of the battle. I honor you for your own experiments with leaving equipment outside in the snow. Regarding the battle, I think you were mislead on many points by Petre et al. I do not want to come across as self-promotional, however my book, “Crisis in the Snows: Russia Confronts Napoleon the Eylau Campaign”, co-written with Ralph R. Reinertsen, uses a much more complete set of primary sources than the authors you cite. We devote twelve pages to Murat’s charge, which, we calculate involved 5,000 troopers (for example all the dragoon divisions had three squadrons per regiment, not four; Grouchy and Klein had four regiments each, not six). This is not to take away from your thoughtful work, but merely to say that I think our work has greatly expanded and in many cases debunked some of the sources you relied upon.

Dear James,

Thank you for visiting the site and your comments on my Eylau article.

The problem still remains, regardless of new sources or debunked old ones, that the field was covered in snow and that it was well below zero throughout the day of battle. I still consider that both sides just lumbered at each other, rather like two worn out boxers throwing punches in slow motion.

I plan a trip to the site in 2019 to meet a group of local historians who are studying the battle and attempting to examine the field in detail. I will keep you posted.

Best regards,

Graham

Dear Graham,

I envy you your trip.

Regarding Eylau: if you like, send me a contact point and I will e-mail you the part of my book that relates the cavalry actions (both Hof and Eylau) as I understand them.

Cheers,

James

“the fact that no army or portion thereof would attack an enemy in a prepared position without artillery support;”

Yet, that is precisely what you say occurs when the French 18th and 26th are sent against the Russian rearguard positions before Eylau.

Dear Thomas,

Thank you for visiting the site and comments submitted.

The French attack without artillery support before Eylau cannot be called an attack against a prepared position, since the Russians were only attempting to slow the French down before retiring to their main positions beyond the village.

Thanks for the useful and insightful essay!

Regarding swabbing the cannons, though: a fired cannon would be extremely hot. I would imagine that any snow thrust down it would melt instantly.

Thanks for visiting the site Rachel!

I do not think that snow would do the trick, thrust down the barrel. A wet sponge contains just enough water to clean out the residue from a previous firing, however, a load of snow conjures up problems concerning how much will steam off and how much will still be sloshing about in the barrel?

Best Regards,

Graham J.Morris (Battlefield Anomalies)

I WISH someone here would make these great articles into .pdf format. Usually I can make them w/relative ease, but not on this site.

It would great to be able to download these with ease for future reading at one’s leisure.

Thanks

Correction…I found out a very easy way of creating and downloading .pdf’s. All is well!