Introduction

The battle of Malplaquet was one of the bloodiest contests in modern history. Its “Butchers Bill” was by far the worst of any engagement fought during the War of Spanish Succession, and the shock wave that it engendered reverberated through all strata of what today we consider to have been a polite and genteel society. The dawning of the Age of Reason had caused a shift in the political outlook of most Western European countries, and governments now looked toward the economic virtues of trade rather than religious intolerance. Thus the d toll at Malplaquet was to traumatize the nations of Europe just as much as the horrific loss of life at the Somme and Verdun were to do some two hundred years later.

The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 brought to an end the Thirty Years War, which had ravaged Europe not only with bitter-armed conflict, but also with pestilence, and the atrocities committed by all sides caused military thinkers to revaluate their whole concept of warfare. By 1700 the art of war had became the art of manoeuvre, and in particular the art of fortification and siege craft. Campaigns were normally fought during the spring and summer, armies going into winter quarters in October and emerging once again in April to continue their chess- like manoeuvring. Armies were now far more disciplined in comparison to the marauding hordes of mercenaries employed during the Thirty Years War, and although foreign troops were still used in most armies of the period, they were subject to the same stringent measures of discipline as the indigenous soldiers of the country under which they served.

Weapons and tactics had also changed. Between 1648 and 1703 the pike gradually became obsolete, and infantry were now all armed with the flintlock musket and the socket bayonet. With the adoption of one single weapon, battlefield tactics and formations were simplified, and the battalion became the basic unit of most armies. Each battalion was around 600-800 strong and organized into left and right wings, these again being subdivided into divisions and platoons, eighteen platoons normally made up a battalion. The French still continued to use the traditional method of firing by ranks, but the English and Dutch armies had begun to use platoon firing. The effectiveness of this type of “rolling” fire meant that each platoon gave three controlled volleys along the whole front of the battalion from right to left as follows, ‘After the battalion formed up, the line was sub-divided into 18 equal platoons of 30-40 men, half the elite grenadier company taking post at each extremity of the line. The platoons were then told off into ‘firings’ of six platoons apiece, not contiguous groups, but scattered proportionately down the line. Sometimes the fire of the entire front rank would be also reserved as a fourth ‘firing’. The colonel (or deputy) and his pair of drummers took post to the fore of the centre, the second- in-command and the colour party drew up to the rear, whilst the major and adjutant hovered on horseback on the extreme flanks, ordering the lines. A subaltern and a sergeant were told off to supervise each platoon, any spare officers taking up positions in the rear of the battalion line. After advancing towards the enemy, the battalion would halt at 60 yards range. On the order ‘First Firing, take care!’ the platoons of the first six platoons would prepare to discharge, giving fire together in a patterned sequence. Next, as these platoons opened order to reload, the platoons of the second firing would come to the present and fire in turn. The remainder, which included the grenadiers, then gave the third fire. By this time (approximately 30 seconds), the first sub-units would have finished reloading and would be ready to fire a second time, and the whole process would be repeated’.

Drill, drill and more drill kept the battalions in alignment, and also enabled the troops to reload smoothly and rapidly. The problem that confronted both armies at Malplaquet was that once any obstruction, such as a wood or boggy meadow had to be negotiated, then harmony was lost and the whole line could falter.

Cavalry were used as shock troops against the flanks or rear of an opposing army, and against disordered infantry. Where cavalry encountered cavalry the French sometimes still continued the practice of firing their carbines and then filing to the rear to reload while the next rank came forward to fire in their turn. By the time of Malplaquet however, the French were beginning to use their mounted arm for counterattacking, using the sword as much as the carbine. The Duke of Marlborough preferred to use the Allied cavalry for pure shock tactics, and only allowed three charges of powder and shot for each trooper, and these were only to be used for guarding the horses while they were grazing, the sword was the sole weapon to be used in action. The main tactical unit was the squadron, several of which were combined together into regiments. Each squadron numbered approximately 150 men and horses.

Artillery was cumbersome and consisted of 12-24 pound cannon (the weight applying to the size of ball used in each), normally dragged to the battlefield or siege lines by civilian teamsters contracted for the duration of the campaign. At Malplaquet both sides used their artillery to good effect grouping them into batteries and, as in the case of some of Marlborough’s guns, moving them forward to give support to the infantry attacks. The English army had also begun to attach small 1-3 pound cannon to each of their battalions so as to give close support and added firepower during the advance; however few, if any of this latter type are mentioned at Malplaquet, and in the main the larger calibre guns were the only kind used.

After their resounding defeats at the battles of Blenhiem (1704), Ramillies (1706) and Oudenarde (1708), the French began to appreciate Marlborough’s tactics on the battlefield. Their commander at Malplaquet was Marshal Claude-Hector, Duc de Villars, an outstanding and competent leader for all his bluff and bluster, and the man on whom King Louise XIV placed his last hope of staving off an allied invasion of France. Villars field army numbered some 80,000 men, made up of French, Bavarian, Swiss and Irish contingents. These consisted of, 121 understrength battalions of infantry (300-400 men each), 260 squadrons of cavalry and 80 cannon.

The reputations of John Churchill, First Duke of Marlborough, and Prince Eugene of Savoy have been passed down to us without diminishment over the centuries. Their partnership on and off the battlefield was one of complete understanding, trust and harmony, and they were arguably the greatest “team” in military history. At Malplaquet Prince Eugene and Marlborough effectively had joint control over the entire battlefield. The combined allied army was made up of Dutch, Prussian, Hanoverian, Irish, Swiss, Danes, Scots, Hessians, Saxons, and English troops numbering 110,000, and formed into 128 battalions, 253 squadrons, with 100 cannon.

Background

The War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714) came about as a result of the uncertain health of the childless Spanish King, Charles II. The three main claimants who contested the right to the throne of Spain were Louise XIV of France, on the behalf of his eldest son, Philip of Anjou, who was a grandson of King Philip IV of Spain; the Prince Elector of Bavaria, Joseph Ferdinand, a great grandson of Philip IV; and the Holy Roman Emperor, Leopold I, who claimed the succession on behalf of his son, The Archduke Karl. Both Holland and England were opposed to any union that would make France even more powerful than she already was, but like France, were also not willing to see the Archduke Karl on the throne of Spain for fear of seeing the re-assertion of Hapower in Spain.

Of the three claimants, Bavaria was by far the weakest, and therefore the most likely to be accepted by the English and Dutch as it seemed to offer the best guarantee of preserving the balance of power in Europe. Louise XIV, also not wishing to see a resurgence of Austrian control across the Pyrenees, signed the Treaty of Partition with England and Holland in 1698, in which the young Bavarian prince, Joseph Ferdinand should inherit the throne of Spain, together with her empire in the Indies. The unexpected death of Joseph Ferdinand the following year (1699) caused the Second Treaty of Partition (1700) to be negotiated, whereby France, Holland and England agreed that France was to receive Naples, Sicily and Milan, with the rest of the Spanish dominions going to the Archduke Karl. This arrangement proved to be unacceptable to the Austrian Emperor, who claimed the whole of the inheritance for his son.

When Charles II died in November 1700, it was discovered that he had left a will in which he bequeathed his Empire to Philip of Anjou, with the provision that if the bequest was not accepted in its entirety the throne would be transferred to the Archduke Karl of Austria. Since no side would now consider stepping back in order to rearrange a more prudent transference of the whole Spanish Succession, Europe found herself once more plunged into war, as Louise XIV now set his mind on military aggrandizement and still more territorial gains. He flouted convention, and poured troops into the Spanish Netherlands, he took possession of Dutch towns, and forced the Spanish to hand over all of their African slave trade with the Spanish Indies to France. His aggressive acts caused the Dutch and English to realize that they would have to fight for their commercial existence, and propelled the Austrian Emperor into their arms as a welcome ally.

The first round of the war was fought in Italy in 1701, where Prince Eugene of Savoy, in command of the imperial forces, brilliantly outmanoeuvred and defeated Marshal Nicolas Catinat and Marshal Francois de Neufville, Duke of Villeroi. The dilatory behaviour of the Dutch caused Marlborough to begin his campaign in the Low Countries with caution, but during 1702-1703 he managed to capture a number of important towns including Huy, Limburg and Bonn. However the French were compensated by successes in Alsace, which enabled them to threaten Vienna.

In the spring of 1704 Marlborough embarked on his famous March to the Danube, successfully transferring his army from the Netherlands into Bavaria. Here he was joined by Prince Eugene and together they defeated the French and Bavarian forces at the battle of Blenheim (August 13th 1704). The battle cost the French Bavaria, and the capture of Gibraltar, also in 1704,was another body blow to Louise XIV’s ambitions.

In 1705 Eugene was defeated at the battle of Cassano in Italy by Marshal Louis Joseph Vendome, while Marlborough gained only limited success in the Netherlands. The tables were turned once again in 1706 when Marlborough scored a resounding victory at Ramillies (May 23rd), and Eugene crushed the army of Marshal Marsin and the Duke of Orleans at the battle of Turin (September 7th).

The year 1707 was one of misfortune and disappointment for the allied cause. Eugene was checked in Provence, and Marlborough made little progress in the north. Both commanders did however score another brilliant victory over the French in 1708 at Oudenarde (11th July), which opened the way for the capture of Lille and drove the French back within their own borders.

The Campaign of 1709.

The peace negotiations that took place during the spring and early summer of 1709 had reached deadlock, with neither party willing to concede ground. Louise XIV, under pressure from all sides, now became determined to reject all proposals and terms outright. He now entrusted the salvation of France to Marshal Villars, saying, ‘All I have left is my confidence in God and in you, my outspoken friend’.

The ravages of the previous campaigns, together with one of the worst winters in history had left their mark on the once mighty French army. Bread was in short supply, and the materials of war, such as shoes, uniforms and muskets were all lacking. In a magnificent show of patriotic fervour, the French peasantry came forward in droves to offer their lives and service for the salvation of their country, and slowly the regiments began to build up into something resembling a respectable fighting force, but the battalions were well under strength. Grand schemes such as the retaking of Lille, or a surprise attack on Courtrai had to be ruled out as totally impractical given the state of the French army, and therefore a defensive policy was adopted in which Villars proposed the building of containment lines between the Douai and the Upper Lys. With these lines in place the French army could prepare itself for further operations.

Having assembled their army at Ghent, Marlborough and Eugene began to advance on Courtrai on June 13th. A reconnaissance was carried out to discover the strength of the French lines, and although still incomplete, they were nevertheless found to be formidable; therefore an alternative plan was implemented which put aside any form of mobile warfare in favour of the siege of Tournai.

Manoeuvring as if to strike at Ypres or Bethune, the allies bluffed Villars into moving troops from the garrison of Tournai to meet the threat; as he did so they moved rapidly towards Tournai, which they invested on the 27th June. However, Villars was not unduly perturbed, as his real weak point had been Ypres, and the modern defences, plus the remaining substantial forces in Tournai, some 7,000 men, gave him confidence of being able to withstand a protracted siege.

On September 3rd Tournai capitulated to the allies at the cost of 5,340 casualties. The French lost some 3,000 men during the siege, and a further 300 officers and 3,325 men were paroled.

To keep up the pressure the allies now marched on Mons, which was invested on September 6th. This came as somewhat of a relief to Marshal Villars who was far more concerned for the safety of Ypres, however Villars was nevertheless eager to confront the allied army when a favourable moment presented itself, and he now moved his entire force into a covering position south of Mons, near Malplaquet. It was on the rolling fields and woodlands around this little French village that Marlborough decided to engage and crush the last army of France.

The Disposition of the Opposing Armies.

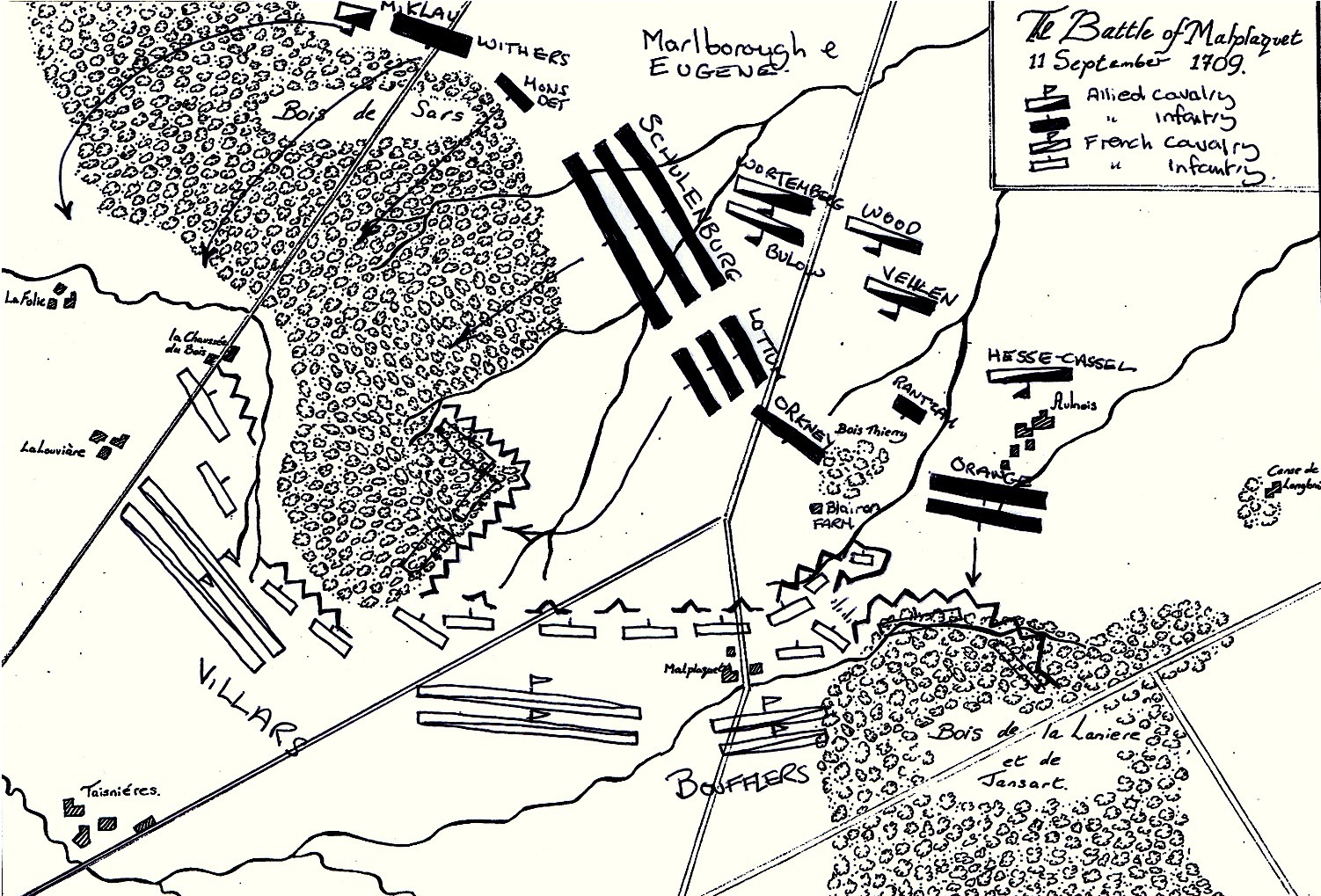

The position taken up by the French army extended from the North West, at the village of La Folie, which marked the extreme left of their line, across the undulating meadows running South East to the Chausee Brunehaut road and the Wood of Lainieres, which secured their right flank. Across the entire front of this line Villars had constructed field works and entrenchments, which included, in the centre, five redoubts. The Wood of Laineres had been fortified with lines of breastworks, and abbatis placed forward to slow down the attacking columns. In front of the French left wing stretched the Wood of Sars (also sometimes called the Wood of Taisnieres). Villars had incorporated the southern tip of this wood within his main battle position, and, as with the Wood of Laineres, had prepared it for defence by building breastworks and earthworks also protected by lines of abbatis.

Villars had been joined by Marshal Louise Francois, Duc de Boufflers, whom he now gave command of the French right wing. Here were ranged some 63 battalions of infantry. On the extreme right, occupying the fieldworks and Wood of Laineres was General D’Artagan with 46 battalions and a six-gun battery. A small depression in the ground crosses the battlefield from near the village of Aulnois and cuts its way into the French position at this point, and as well as incorporating the re-entrant which this made into the line of his entrenchments, Villars also made it into an ideal place within which to conceal a twenty gun battery so as to enfilade any troops attacking across its front. On D’Artagan’s left, occupying the breastworks that overlooked the Farm of Biairon, General De Guich was positioned with 18 battalions, with a twenty-gun battery on his left at the point where the first of the five redoubts covering the French centre was situated. Here thirteen battalions held the line of redoubts, with four more in support. Thirty cannon had been sighted in front and to the flanks of this these works. To the left again came the projecting tongue of the Wood of Sars, which was occupied by General Albergotti with 21 battalions lining the entrenchments within, and at the forward edge of the wood itself. A five-gun battery was placed at the centre, and in close support of this line. To the left again came General Goesbriand with 17 battalions of the extreme left wing. To the rear of the infantry lines Villars deployed his cavalry, which included the Maison du Roi and the Gendarmerie. In all some 180 squadrons. Villars stationed himself near the village of Malplaquet.

Marlborough and Eugene reconnoitred these strong fortified lines on the 10th of September, and decided upon using the same overall tactics that had brought them victory at Blenheim. The French right and left flanks would come under heavy attacks causing Villars to draw off troops from his centre to contain them. When the French centre became suitably weakened, the allied infantry reserve would advance to occupy the central redoubts, allowing the massed squadrons of their cavalry to pass through and secure victory. To this end 40 allied battalions under General Schulenburg, in three huge, deep and compact lines, would move against the northern face of the Wood of Sars. This attack was supported by a twenty-gun battery, plus a contingent of 1,900 men called in from the siege of Mons who would march into the woods even further north to cover the allied right flank. On Schulenburg’s left, General Lottom with 22 battalions, and supported by a forty gun battery and 30 squadrons of cavalry under The Prince of Auvergne, would march as if to attack the French central redoubts, but at the last moment he would make a turn to his right, throwing his whole weight against the French troops of General Albergotti holding the tongue shaped salient of the Wood of Sars, at its southern extremity. The Allied centre under the command of Lord Orkney, consisted of 15 battalions of infantry including 11 British, were stretched in a single line from Lottums left, across to the small wood of Tiry, and were backed by a powerful force of some 179 squadrons of cavalry. The allied left wing was commanded by the young Prince of Orange, but tempered by the sage- like, if not always welcome, advice of generals Tilly and Oxenstiern. Much debate has occurred over the actual roll that was to be played by the Dutch forces on this wing. Certainly the Prince of Orange himself was under no illusion, and considered that his part in the battle consisted of penetrating and destroying the French to his front. It does indeed seem that the task allocated to this wing was to have originally been far greater, and the Prince may be forgiven for thinking that his main objective was to drive-in the French right flank. His original force was to have been 49 battalions and 32 squadrons, supported by eighteen cannon, but 19 battalions under General Withers, together with 10 squadrons commanded by General Miklau had been diverted to the extreme allied right wing to be used in a flanking attack against the left and rear of the French line, in itself a novel idea during this period. Unfortunately for the Dutch Prince, Marlborough was not one to confined his plans to his subordinates, and it is quite possible that, like the attack on the Wood of Sars by Schulenburg and Lottum, the Prince of Orange took it for granted that his part in the battle was to do all he could to overrun the French right wing, not merely contain it?

The Allied front covered some 6,000 meters and, unusually for those times, the views across it were very restricted owing to the various woods and coppices, which reduced the field of vision greatly for both armies. Marlborough himself took station behind Orkney’s British battalions, while Prince Eugene marched at the head of Schulenburg’s second line.

The Battle.

The chill of a September night gave way to a foggy dawn, and the mists rising from the marshy ground and the silent woods shrouded the concentration of the allied army. Around 7.00 am the sun began to shred the fog into long vaporous ribbons which quickly burnt away as the ground began to warm, and by 8.00 am the opposing artillery were exchanging a sporadic fire across the battlefield. At 8.30 am Marlborough gave the order for the great battery of forty allied cannon to fire a single salvo as a signal to commence the attack.

Like ripples on water, the 83 battalions of the Allied right wing began to advance over the 700 meters of ground that separated them from the Wood of Sars and the formidable entanglements and breastworks of the French forward line, which stood silently awaiting the order to open fire. As the range closed to 50 meters the edge of the woods erupted in a mass of flame and smoke, the air became filled with musket balls, like so many angry bees speeding towards their tormentors. The first volley mowed down hundreds of men in Schulenburgs first line, and caused their comrades in the rear ranks to loose step as they sort to avoid the bodies of the dead and wounded. In less than a minute, another deafening crash roared out from the French line, as their first ranks stepped back to allow the second rank to deliver its fire. The advancing German battalions under Schulenburg, some twenty thousand strong, lost their cohesion as the defending French brigades poured volley after volley into the struggling masses before them. General Withers and the contingent from Mons plunged into the woods farther out on Schulenburg’s right and met with no resistance as they endeavoured to force a passage through the tangled undergrowth and strike at the French flank. Things were very different on Schulenburg’s left. Here General Lottum’s 22 battalions, in three lines, became mired in the marshy bottomland as they attempted to skirt the wood and come in against the tongue shaped salient at its southern extremity. Watching these movements, the French artillery commander, General St Hilaire, rushed forward a fourteen-gun battery outside of their main line of redoubts, which enfiladed Lottum’s columns as they swung to their right, ploughing bloody lanes through the whole of his formation, while his front ranks were riddled with musket fire at close range from behind the parapets lining the wood. Eager to get away from this killing field, Lottum’s infantry threw themselves upon the abbatis on the outskirts of the wood, and tearing them away with their bare hands, they endeavoured to come to something like even terms with their enemy; however it would take almost three hours of bitter exchanges and mounting causalities to gain a toehold in this part of the French position.

Away on the allied left the Prince of Orange began his attack at around 9.00 am. Riding at the head of his 30 Dutch, Swiss and Scottish battalions the prince’s main effort was aimed at the French works along the edge of the Wood of Lanieres, defended by General d’Artagnan’s regiments which included amongst them such illustrious names as Lorraine, Piémont, Royal Roussillon and the Gardes Francaise. At 90 meters the hidden French battery of twenty cannon that had been positioned in the re-entrant of the d’Artagnan’s fieldworks, let fly with a tremendous belch and roar of flame, which swept away whole ranks, leaving the ground littered with mangled and torn bodies. Still the battalions pressed on, receiving yet another awful raking fire from the French guns, and now also the massed volleys of over three thousand muskets as the French front line erupted in a hail of fire. General Oxenstiern was killed, and over two thirds of the Prince of Orange’s staff fell around their leader. Down went the prince’s horse; shot through by a shower of missiles, but the gallant young man himself remained unharmed and advanced on foot. The ground became so choked with the bodies of the dead and writhing wounded that all attempts to form a coordinated firing line became impossible. Half an hour after starting their advance the Dutch, Swiss and Scottish battalions had suffered some 5,000 casualties. But even this did not prevent the prince from pulling back to reform his battle lines, and once again advancing into the hurricane of lead and iron. In a repeat performance of their previous courageous, but futile endeavours to close with their opponents the allied battalions melted away in the face of the massive concentration of French fire. The Dutch Blue Guards left over half their strength on the field together with Generals Spaar and Hamilton, and the attack petered out and retired, still in good order, leaving the ground carpeted with even more dead and wounded. The Farm of Blairon, which had been captured during the advance, had to be abandoned and was now once again in French hands.

Seeing an opportunity to deliver a bayonet charge to complete their work, the French regiments of Picardy and Navarre advanced beyond their entrenchments, and were about to push on with cold steel when they were checked by the 21 allied squadrons of Hesse-Cassel, who moved his troopers forward to cover the Dutch retirement, and General Rantzau who moved two Hanoverian battalions from the central reserve in an attempt to meet the French advance. These battalions were however received with such a galling fire that soon they too were forced to retire with much loss of life. Rantzau wrote after the battle, ‘ Monsieur de Goslinga, passing at full gallop, came to me and asked me if I did not wish to advance; I answered that he could see quite well that I was advancing, that it might please him to order the Prussians on my right to make the same movement, and to march forward like me, considering I had too little with two battalions to carry through the affair alone. Monsieur de Goslinga thereupon stopped a moment, and in his confidence of victory, or perhaps seeking to encourage the soldiers, shouted, “La batallie est gagnee, ha! Les braves gens!” After which [says Rantzau somewhat maliciously] he departed, all the more quickly since the enemy had forced our left [i.e. the left of Fagel’s assault?] to abandon the entrenchment.’

A full scale attack by the French on this section of the field could now have given them victory, but Marshal Boufflers, possibly considering that he was under orders to conduct only a defensive battle, held back, and the chance to deliver a decisive blow never materialised.

While the Allied left wing endeavoured to untangle itself and regroup its shattered battalions, General’s Schulenburg and Lottum pressed their attacks on the smoke choked wood of Sars. At 10.00 am Schulenburg had managed to break through the entanglements along the north side of the wood, forcing the French here to fall back into its murky depths and form a new line of battle. Lottum’s command however was still unable to penetrate the southern salient, and suffered terribly from the French enfilading cannon fire, as well as from the constant volleys of musket and cannon fire against their front. Two fresh British battalions were now sent in by Lord Orkney to bolster Lottum’s left flank. As these troops moved forward General Chemerault, who commanded the left of the French line of redoubts, brought forward twelve battalions of infantry, intending to throw them against Lottum’s disorganized left flank. It was at this crucial moment that Marlborough himself rode forward, accompanied by The Prince of Auvergne with 30 squadrons of cavalry, to view the situation on this part of the field for himself. Immediately the Duke ordered Auvergne to deploy his cavalry in readiness to charge Chemerault’s battalions, who were themselves unaware of the threat from the allied cavalry. Fortunately for Chemerault, marshal Villars had now also ridden over to this section of the battlefront and at once saw the danger. He cancelled the orders for the twelve battalions to counterattack, and instead moved them to the western outskirts of the Sars salient, there to bolster his infantry within the wood itself who were now slowly being forced back by the sheer weight of numbers. Thus Villars began to weaken his centre to support his left, just as Marlborough had anticipated.

Now safe from any French counterattacks, Lottum’s depleted command, together with Orkney’s two fresh British battalions finally burst into the southern tip of the Wood of Sars, pouring over the entrenchments and finally coming to grips with their adversaries using the bayonet and clubbed musket. The fighting here must have been terrible, as thousands of men yelled, cursed, screamed, gouged, kicked and tore at each other within no more than 600 square meters of woodland. Those that could still re-load in the crush, fired without heeding the drill-book regulations, but just banged off shot after shot as fast as they could. The officers who had managed to survive the initial attacks also took part in this hand-to-hand struggle, slashing to right and left with their swords, or taking up a musket and fighting like a private soldier, although their gaudy uniforms, decorated with silver and gold lace marked them out as special targets. This woodland fighting must have been quite exceptional for its time, and one can only guess at what it must have entailed -the stifling clouds of smoke that only gradually drifted up into the treetops; musket balls coming in from all sides, sending leaves and twigs cascading down to the ground as in an autumn storm; flying wood splinters piercing eyes and flesh and turning men frantic among the welter of death and destruction that surrounded them, while flocks of birds wheeled overhead in perplexed agitation.

Around 11.00 am, while Schulenburg and Lottum were fighting their way into the stricken woods, Marlborough was joined by Prince Eugene and both now rode over to the left flank, summond there by urgent calls for reinforcements, ‘What he found there horrified him, but he arrived in time to countermand a third assault which the hot-headed Prince (of Orange) was about to unleash against Boufflers positions.’ For once Marlborough’s normal battlefield intelligence was sadly lacking, and he had been totally in the dark as to the events that had taken place on this section of the field. Only now did he realize the folly of not explaining his battle plan in more exact terms to the young Dutch Prince, and the fact that the Duke himself accepted full responsibility for the slaughter shows that he also understood the implications of not taking the prince into his confidence.

Having made sure that no more suicidal attacks would occur, and that the role of the left wing was to only contain the French, Marlborough and Eugene rode back to the centre to await news of the combat in the Wood of Sars. It was now 11.30 am, and the smoke and noise were still indicative of the continuing violence near at hand, where close to thirty thousand Allied infantry pressed forward against four or five thousand French defenders, trampling friend and foe alike underfoot. Many became crazed killing machines, ‘Sir Richard Temple’s regiment lost more men that day than any other single British battalion. They performed prodigies; but their high spirits took a savage form. “They hewed in pieces” wrote a German observer, “all they found before them…even the dead when their fury found no more living to devour.”‘ The French put up a gallant resistance, which caused the allies to pay for every inch of ground with their blood, but even as they withdrew it would appear that other obstructions had been made ready to confront their antagonist after the first line of entrenchments and breastworks had been breeched. Corporal Matthew Bishop of the 8th Regiment of Foot has left us a tantalizing glimpse of how the French had fortified even the interior of the woods.

“The Enemy had the advantage of the wood, which would have rendered them capable of destroying the greater part of us, had they not been intimidated. When we came near the wood, we threw all our tent poles away, and ran into it as bold as lions. But we were obstructed from being so expeditious as we should, by reason of their artful inventions, by cutting down trees and laying them across, and by tying the boughs together in all places. This they thought would frustrate us, and put us into disorder, and in truth there were but very few places in that station in which we could draw up our men, in any form at all; but where we did, it was in this manner. Sometimes ten deep, then we were obstructed and obliged to halt, then fifteen deep or more, and in this confused manner we went through the wood, but yet all in high spirits”

In the centre the opposing artillery kept up a constant exchange of fire; but further off to the right, in the murky depths of the forest Wither’s battalions and squadrons, the latter having been reinforced by a further ten squadrons sent over by Eugene, were still struggling to clear the timber and find the exposed French flank.

The French commander was also well aware that his positions within the woods were susceptible to being turned, and he now decided to form a second line of defence ready for the time when the allied battalions finally broke cover from that nightmare world. Once again Villars conformed to Marlborough’s plans, and drew still more battalions from his central redoubts. This time it was the turn of the Irish brigade, or “Wild Geese” as they were more famously known, together with the French Regiment of Champagne who both now moved to the left wing. The Irish brigade seem to have plunged into the wood itself, as most sources mention an encounter that took place between them and their counterparts in the British army, the Royal Regiment of Foot of Ireland. Not long after Villars also withdrew the whole of the Bavarian brigade and placed it with the forces on his left, thus leaving the whole of his centre almost totally devoid of defenders.

While the French Marshal was busy trying to deploy sufficient forces to meet the allied attacks on his left, Marlborough and Eugene had now ridden forward, at around 12.15 pm, through the woods, to view the situation for themselves. It was here that Eugene received a wound which nicked the side of his neck, just behind the left ear. With customary nonchalance, he refused to have the wound attended to, saying, ‘If we are to die here it is not worth dressing, if we win, there will be time to night.’ Somehow the resourceful Schulenburg had managed to drag seven 12-pounder cannon through the woods, in spite of the difficulties, and these were now firing into the long lines of French cavalry drawn up on the plain, causing many casualties, and forcing them to retire out of range. No longer having these glittering masses as a target, the allied cannon now switched to the French breastworks in this area, raking many of them with enfilading fire. Schulenburg now ventured to advise the Duke that this would be an opportune time to send forward his central battalions to occupy the abandoned French works. Without delay, Marlborough sent an order to Lord Orkney, together with another to Hesse-Cassel and Auvergne to be prepared to support him with their cavalry, and at close on 1.00 pm,

‘…my 13 battalions got to the entrenchments, which we got very easily for as we advanced they quitted them and inclined to their right. We found nothing to oppose us. Not that I pretend to attribute any glory to myself, yet I verily believe that these 13 battalions gained us the day, and that without firing a shot almost’

Orkney may have not wished to steal any of the glory for himself, nevertheless his 13 battalions certainly made all the difference in the centre, where only a few battalions of the French Guard remained, and these only put up a token resistance before abandoning the central redoubts completely. Villars position was, to all intents and purpose, now cut into.

Villars received the news of the occupation of his centre while he was still preparing for his counter-stroke against the Wood of Sars. As he turned in the saddle to converse with General St Hilaire he was hit by a musket ball that passed through his high top boot, and penetrated below his left kneecap, shattering the bone. Trying for a time to regain his composure, he soon collapsed from the loss of blood, and had to be carried from the field. A second musket ball caught General Albergotti in the thigh knocking him out of the saddle, and a third hit General Chemerault killing him instantly. The command of the French left now devolved upon General Puysegur, who having command thrown upon his shoulders in so unexpected a manner seems to have become overwhelmed by the sheer magnitude of his situation. It is quite possible that Puysegur was unaware that Villars intended to counter attack the allied troops as they debouched from the Wood of Sars, or of the imminent advance of the allied cavalry in the centre; whatever he thought or knew he did nothing, having his mind set more on saving the French army rather than taking any bold measures to obtain victory.

While these changes were taking place the flanking units of Withers began to make their appearance on the far left of the French position, having finally managed to beat a path through the woods, arriving just to the north- east of the farm of La Folie. The cavalry squadrons under General Miklau had arrived further out on Withers right, and had begun to shake themselves out from column of march into line, when they were hit on their right flank by General M.de Rozel with ten squadrons of French carabiniers. With no infantry support close enough at hand to give assistance, Miklau’s cavalry were cut to pieces; the survivors taking refuge once again inside the wood it had taken them so long to negotiate.

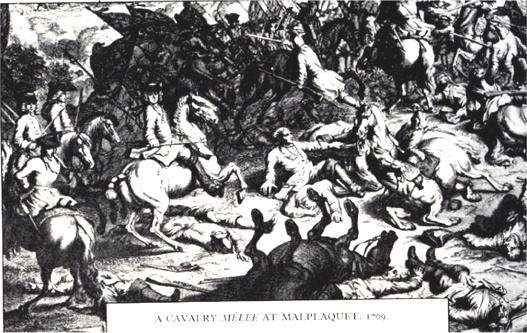

It was now 1.30 p.m. and in the centre squadron upon squadron of allied cavalry began to pour around the French redoubts held by Orkney’s battalions and pass onto the plain beyond. The first to deploy were the twenty Dutch squadrons under General Auvergne, who were immediately charged by the elite French cavalry regiment of the Maison du Roi, led forward by Marshal Boufflers himself, who had now taken overall command of the army. The Dutch were forced back by the sheer momentum of the charge which was only brought to a halt by the steady platoon fire of Orkney’s infantry, supported by ten cannon brought to the front from the great battery. Sheering off to the right and left, the French cavalry retired in their turn, once again allowing the allied squadrons to pass through the redoubts. As before Boufflers led another charge, this time calling in more and more cavalry until the whole plain between the redoubts and the village of Malplaquet became one vast swirling cavalry melee. Each time the French pushed back the allied squadrons, they were forced back in their turn by cannon and musket fire, “I really believe had not ye foot been there,” wrote Orkney, “they would have drove our horse from the field.”

Still Boufflers would not be denied. In all he mounted six separate attacks on the allied squadrons as they endeavoured to form on the plain, but in the end freshness and numbers began to tell. Soon Prince Eugene, at the head of the regiments of horse under Bulow, Wurtemberg, Vehlen, Wood, Hesse-Cassel and Auvergne seethed onto the plain in one herd like mass of over 25,000 men and horses. Pulling his squadrons back from their futile attempts to stem the tide of hostile horse passing through the redoubts, Boufflers now concentrated his own main cavalry mass, possibly amounting to some 15,000, on the heath land around Malplaquet. Here for the next hour the conflict raged, as men and horses rode at each other slashing with their swords or discharging their firearms into each other’s faces. Clouds of dust enveloped friend and foe alike, powdering uniforms and making distinction difficult, while wounded horses, maddened by pain and fear attempted to kick their way free from the crush.

On the French left General Puysegur ordered his troops to fall back towards Quievrain, possibly noting that Boufflers had become far too embroiled in the cavalry battle in the centre to consider any overall plan for the salvation of the army. The Allied battalions on this wing were far too exhausted by their efforts to follow their enemy, who still managed to show a bold face, and marched off the field in good order. On the right the Prince of Orange now judged the time right for another advance, which was only half heartedly contested by General d’Artagnan. For his part d’Artagnan, like Puysegur, saw that the game was up, and pulled back his forces towards Bavay and Maubeuge, once again in very good order. Being informed of the withdrawal of both wings of his army Boufflers now proceeded to untangle his squadrons, and in a supreme piece of General- ship, he managed to manoeuvre his squadrons so as to cover the retreat of the whole army.

The battle died down at just after 3.00 p.m. with no pursuit forthcoming from the Allies, who were close to exhaustion after seven hours of bitter fighting. Many sank down on the spot, others looked for water, while some took to looting the bodies, which were plentiful. The whole field was covered in dead and wounded men and horses. In front of the French entrenchments along their right wing the bodies of the Dutch, Swiss and Scottish lay four or five deep, with small hope of survival for any of the wounded that might lie below the dead weight crush of the corpses. Before the re-entrant where the 20 gun French battery had been concealed, the mutilated remains of the Dutch battalions of general Dohna lay in ghastly windrows. Severed arms legs and heads lay among blackened torsos which were strewn in all directions, the whole expanse of ground, some 1000 meters wide by 100 meters in depth from the Wood of Tiry to the Wood of Lanieres being one vast carpet of pain and death.

Inside the Wood of Sars the picture was even worse. Here the restrictions of the trees themselves made the slaughter even greater. The press and crush of so many thousands formed a human wall into which even the unreliable muskets of the day could not fail to find a target. It has been estimated that 7,000 men, of all nations were killed or wounded in the Sars salient alone, these not counting the casualties that occurred before the Allied troops entered the woods, or after passing through it.

The central part of the battlefield appeared less gruesome, that is until the French redoubts were passed. On the wide plain stretching from the rear of these fieldworks to the outskirts of Malplaquet village, hundreds of men and horses lay like so many discarded bundles. The ground was covered with broken swords, hats, discarded cuirasses, saddles and harness. Riderless horses either dashed to and fro or stood quietly nibbling the grass, while others tried pathetically to rise from the ground, only to fall back again in their agony. Wounded men attempted to crawl away anywhere to seek help, while others cried out for water. The whole countryside for miles around echoing to the screams of the surgeon’s knife.

The cost in life may never be fully known. Most sources state that the Allies lost 25,000 men, the French, between 10,000 and 15,000.These figures do not allow for those men who died weeks, or maybe even months later from their wounds. Records were sketchy, and roll calls subject to misinterpretation at all levels. Whatever the actual figures in terms of death and mutilation, the battle of Malplaquet should be seen as one of the best examples, for future generations of military leaders, to appreciate the difficulties of attacking an enemy in a prepared position by frontal assaults. Marlborough’s attempt at outflanking the French position deserved greater attention both during and after his life time, and the fact that even the genius of Napoleon still failed to grasp its meaning one hundred years later at Borodino, shows just how much had been forgotten.

Malplaquet Today

Considering the changes and upheavals that have taken place over the last three hundred years in both France and Belgium, then the quite fields around the villages of Malplaquet, Aulnois and Blaregnies remain remarkably untouched by the juggernaut of progress. Although the great woods of Sars and Lanieres no longer exist, the modern plantations that now occupy some of their original area give the visitor a very good impression of how the field must have looked on that foggy morning of the 11th September 1709.

When visiting the battlefield for the first time it is quite easy to become disorientated by the many small roads and farm trails that criss-cross the site. My two travelling companions and I discovered that the best plan was to go directly to the village of Aulnois. Here there is a small café, which stands at the intersection of the road leading across the French frontier to the Town of Taisnieres sur-Hon, and thereafter on to Bavay. If you have transportation, then you can park your vehicle near the War Memorial in Aulnois, which stands directly opposite the café, and walk the ground around the outskirts of the village. It was from here that the massed battalions of the Prince of Orange, supported by the cavalry squadrons under Hesse-Cassel deployed before moving to their bloody attacks on the French entrenchments, which covered their right wing from the farm of Blerion to the Wood of Lanieres. It is still possible to trace the line of the re-entrant that cut-into the French position at this point, and which was used to such good effect to conceal their hidden battery of twenty cannon from the approaching Dutch, Swiss and Scottish formations, who were decimated by the enfilading fire from these guns.

The Wood of Tiry, although possibly not being anything like its former size or having the same composition of trees, is nevertheless still represented by a modern coppice, which helps to set the scene when trying to picture the battlefield in 1709. A farm track takes the visitor from Aulnois directly to this group of trees, and then onto the farm of Blairon where Marlborough spent the night of the 11th September after the battle. A plaque on the farm wall commemorates this event. Retracing our steps we returned to Aulnois and then drove to Malplaquet village, passing the now disused and crumberling custom control offices. This part of the field was behind the French front line entrenchments, and was covered by the massed squadrons of French horse. Near Malplaquet itself Marshal Villars established his headquarters. As in Aulnois, the visitors can park their transport in the square of Malplaquet and proceed on foot to explore the surrounding area. I would advise caution when walking the main road that leads from the village northward to the Battlefield Monument, and the French main lines. There are no footpaths, so care must be exercised, always bearing in mind that traffic will be approaching from different directions than it does in England!

It is possible to walk the entire length of the French front line by taking farm tracks and some of the paved roads that cross the battlefield all around this area, and splendid views are obtainable across to the Allied positions running from the edge of the modern Wood of Tiry to the new plantations of trees that cover some of the land on which the Wood of Sars once stood. The fields here are almost all cultivated, and at the time of our visit in May, crops were already quite tall. One would like to be able to obtain some aerial photographs of these fields after the harvest, and preferably during a dry summer, as there are some tantalizing banks and ridges just discernable at ground level, which could well be the lines of the old French redoubts and entrenchments?

The ground has now been subject to modern drainage systems, but here and there one comes across the occasional boggy stretch of land, in particular near some of the small brooks that meander across the plain between Blaregnies and the outskirts of the site of the Wood of Sars. These give a very good impression of what it must have been like for Lottums columns as they wheeled to their right to attack the Sars salient. There is the possibility that some of the mass grave pits can be located, certainly there must have been several of these scattered across the battlefield to accommodate the thousands of bodies that covered the field. One such site could be near the Blairon Farm, while another maybe about two kilometres to the south west of Blaregnies, near where the Sars salient once stood. Here some artefacts have been found, but as yet no firm proof of any human remains; however if eventually these last resting places of so many brave men are discovered, one feels that some form of suitable monument would be fitting to remember them by.

Do not leave without paying a visit to Bavay, and the wonderful little military museum of Messieurs Arthur Barabera, ‘Musee du 11 September 1709.’ Here you will find maps, uniforms, weapons and artefacts dealing with the battle, as well as a friendly welcome. Messieurs Barabera has written an account of the part played by the Swiss regiments who fought on both sides during the battle, entitled, ‘L’Affaire des Suisses a Malplaquet.’ This booklet is well worth reading, and although only available in French, it does contain a great deal of information regarding the battlefield and the various dispositions of the opposing armies.

Unlike Waterloo, the battlefield of Malplaquet has no tourist or trinket shops and maybe all the better for that. One can walk the site and reflect on what must have occurred across these now peaceful meadows without having to be surrounded by coach loads of sightseers, or loosing any of its character by being confronted with a mound of earth with a monument on the top, which destroys any of its features. Possibly a re-enactment group could put on a display of drill and weaponry each year on the anniversary of the battle, other than that I feel that the site should be left very much as it now is.

Some Thoughts on Command and Control.

Considering the need for strict discipline and control to allow each movement and firing drill to be carried out without causing the ranks to become disorganised, then the fighting within the confined environment of the Wood of Sars must have been exceptional for this period. Any change of direction, to the left or right would have been virtually impossible, and the slow ordered advance of 15 meters per minute which could normally be maintained with reasonable precision on open ground was, once inside the constricted entanglements of the forest completely lost.

None of the sources for this great battle deal with the problems of woodland fighting, and for the most part consider that both armies employed the same tactics within this dark tangled mass of foliage and limited vision, as they did in the open. This I find very hard to believe. The fact that Lottum and Schulenburg’s massed columns lost many of their officers “before” entering the wood makes it clear that for the most part it was the non-commissioned officers, and also possibly many of the rank and file themselves who endeavoured to try and keep to the methods drilled into them, until such time as all coherence became totally irrelevant and, madden with fear and hatred they began to fight as a mob.

That the French had more control and command during the initial encounter seems obvious, since they were protected by entrenchments, and therefore less likely to have had as many casualties amongst its officers; also, as we have seen in the description given by Corporal Matthew Bishop (see above), the French seem to have prepared the ground ready for a fall-back through the woods once their forward line was overrun. This in itself shows a remarkable understanding of how to conduct a defence in depth, and is yet another uncharacteristic tactic for this period.

One is reminded of the bitter fighting that occurred in the Wilderness Campaign of 1864, during the American Civil War, and indeed the circumstances are almost identical to the way things took place at Malplaquet. The similarity is so striking that I am surprised that no one has ever bothered to compare these engagements before. In both instances the defending forces had constructed log breastworks and entrenchments covering the approaches to their front, and in both cases the stronger force was cut down in swathes endeavouring to break through the defenders lines. If this is not military history repeating itself without having learnt from its mistakes I do not know what is?

The main question to be asked about Malplaquet from the allied perspective is was it necessary? The French were not defeated, and even had they been forced from the field in more disorder than they actually were, it is by no means sure that the Allies would have had the strength, or the will, to pursue them and complete the victory? Marlborough and Eugene could both be accused of criminal sacrifice of life for no real purpose. One feels that in this, their last joint effort together on the battlefield, both commanders threw restraint to the wind, and were endeavouring to end the war no matter how many of their own soldiers got killed or wounded to do so. Dr David Chandler says that, ‘The pressure in a Marlburian battle was relentless.’ It was relentless for friend as well as foe, and if Malplaquet proves nothing else, it does show that the Duke had begun to consider victory at any price worthwhile.

A note concerning General Withers.

The reader may be wondering why I did not include the troops under General Withers in my initial explanation of the troop dispositions before the commencement of the battle? My reason for not doing so is because I have come to doubt the actual location of this corps when the battle began. It is my opinion that Withers was in the process of marching toward the Allied left wing when he was halted, and diverted by Marlborough and sent on the mission to outflank the French. If this was indeed the case, then it is quite possible that the inordinately long period of time that it is supposed to have taken Withers to negotiate the Wood of Sars, encountering hardly any opposition, maybe in fact due, not to the difficulties of the forest, but because his troops were well on their way to join forces with the Prince of Orange (who was expecting them), when they were recalled by Marlborough on the spur of the moment, and ordered to counter march to the right wing, this being the main cause of delay?

Graham J.Morris. July 2002

Bibliography.

| Chandler | Chandler. David, ‘Marlborough as Military Commander.’ Penguin Books, paperback edition. London 1973. |

| Churchill | Churchill.Winston S, ‘Marlborough His Life and Times.’ Vol IV. George G.Harrap Ltd, Fifth Edition, London 1963. |

| Fisher | Fisher H.A.L, ‘A History of Europe.’ London 1936. |

| Bishop | Matthew Bishop For the writings of Matthew Bishop see, Churchill.W.S. ‘Marlborough His Life and Times.’ Vol IV. |

| Orkney | Orkney, George Hamilton, Earl of:( Four) “Letters of the First Lord Orkney during |

| Cra’ster | Marlborough’s Campaigns” (ed H.H.E. Cra’ster), English Historical Review, April 1904. |

| Sautai | Sautai. M., ‘La Bataille de Malplaquet’, Paris, 1904. |

| Baraera | For copies of Arthur Baraera’s work, ‘L’Affaire des Suisse á Malplaquet’, please write to G.J.Morris for details. |

Graham, Is the museum still there in Bavay? We will be travelling in the area in a few weeks – Malplaquet, Oudenaarde, Fontenoy, Rocroi, Bazeilles, Saint Privat.

Mike

http://www.battlefieldtravels.com

Hi Mike, good to hear from you again.

Sadly, Arthur’s Museum at Bavay is no longer open, as far as I know. The family did not preserve it after his death. You could still ask around the town, especially the Travel Bureau. Someone may have taken over.

Fontenoy is worth a visit, even though the sugar beet factory has ruined much of the site.

Have a great trip!

Graham

Thanks Graham,

Now back from a massive trip. We did visit Fontenoy, the Celtic Cross for the Wild Geese was probably the most memorable site.

Shame about the Bavay Museum. Sometimes it is just one or two individuals keeping the memory alive. I do recommend Patay the next time you are in France – tiny museum run by Regina and Rene, but they are passionate about the history of the battle!

Here are the battlefields I explored on the latest trip. I will be uploading posts on to the website over the coming weeks:

52 BC Siege of Alesia, Julius Caesar vs Vercingetorix

451 AD Battle of the Catalaunian Fields, Hun vs Roman

1346 Battle of Crecy, English archers vs French Men-at-Arms

1415 Battle of Agincourt, English archers vs French Men-at-Arms

1429 Siege of Orleans, culmination of the English kingdom in France

1429 Battle of Patay – Jeanne d’Arc’s revenge for Agincourt!

1429 Battle for the Tourelles, Jeanne d’Arc’s victory at Orleans

1643 Battle of Rocroi, defeat of the Spanish Tercio

1708 Battle of Oudenaarde, victory for the Grand Alliance

1709 Battle of Malplaquet, bloodiest battle of the 18C

1745 Battle of Fontenoy, ‘Wild Geese’ finest moment

1815 Battle of Waterloo, Napoleon’s final battle

1870 Battle of Bazeilles, battle to the last cartridge

1870 Battle of Mars La Tour, closing the trap at Metz

1870 Battle of Saint Privat-Gravelotte, bloodiest battle of the Franco-Prussian War

1916 Battle of Verdun, Fort Douaumont, Fort Vaux

1917 Battle of Polygon Wood, 5th Division AIF in action

1940 Evacuation from Dunkirk, saving the BEF

1942 Raid on Dieppe, a predictable disaster

1944 D-Day, Sainte-Mere Eglise Airborne operations

1944 D-Day, Battle for La Fiere

1944 D-Day, Easy Co 2-506 action at Brecourt Manor

1944 D-Day, Battle of Carentan

1944 D-Day, Ranger assault on Pointe du Hoc

1944 D-Day, Utah Beach

1944 D-Day, Omaha Beach

1944 D-Day, Battery Longue sur Mer

1944 D-Day, Gold Beach

1944 D-Day, Juno Beach

1944 D-Day, Sword Beach

1944 D-Day, German Radar Station 44

1944 D-Day, British airborne operations at Ranville

1944 D-Day, Merville Battery

1944 D-Day, Pegasus Bridge coup-de-main

Mike

http://www.battlefieldtravels.com

Sorry about the delay in replying to your posting Mike, just getting over the festive season.

Sad about Arthur’s museum, it would have been nice if someone had taken it over to keep the memory of Malplaquet alive in the town.

Looks like you had a great trip. Keep on plodding on!

Graham

Graham

I am trying to get in touch with you—but can’t find your present email address.

Paul Goodman

our 2006 Laffelt battlefield visit.

Hi Paul, nice to hear from you once more.

My email address is: grahammorris422@gmail.com

I would also like to have a chat about a return visit to Laffelt I am planning for next year with Leger Travel. I never took any panorama photographs of the site and I would like to get this done before the wheels of progress cover it with brick and steel.

Best regards,

Graham

Dear Sir,

Although I have lost the source of the following, it was whilst I was researching my grandfather’s part in WW1, that I read: “Accounts exist in the Imperial War Museum that further north on the battlefield skeletons had been appearing in sunken lanes and trenches wearing remnants of red cloth and lying alongside bandoliers, muskets and swords all dating to 1709; these were the men who had fought under the Duke of Marlborough at the Battle of Malplaquet. ” The IWM has been less than helpful in this regard and I wonder if you have heard the same. Many thanks.

Thanks for the info regarding Malplaquet Ann.

I have heard many accounts of relics being uncovered around the battlefield but none, to my knowledge has thus far been verified. Arthur Barbera was one of the foremost experts on the battlefield but even he only had a very limited amount of relics from the site inhis Museum at Bavey.

I will contact a few of my fellow historians in France and Belgium and get back with any news.

Many thanks for visiting the site!

Graham J.Morris (battlefield anomalies)

Madam, Sir,

You can see on Malplaquet battlefield, near the farm of Blairon, the new look of the british regiment monument.

It was reconditionned in july 2016 by local council décision.

You can see photos on facebook page : Taisnières Malplaquet culture et patrimoine.

I may send to you more photos by mel.

Regards.

JL Tranchant, Taisnières sur Hon – Malplaquet

Dear Jean – Luc,

Many thanks for the information concerning the Malplaquet monument. Ever since Arthur passed away I have been intending to return to the battlefield. I would also love to have a copy of his work, “The Affair of the Swiss at Malplaquet,” which has some very detailed order of battle lists.

Keep in touch,

Graham (battlefieldanomalies)