July 2nd 1747.

Introduction.

The Duke of Cumberland was the third son of King George II and Caroline of Ansbach. He became known as the “Butcher” after his victory at the battle of Culloden Moor (16th April 1746), where he had ruthlessly ordered that no quarter should be given to the defeated Highlanders. The unfortunate Jacobites were the only army Cumberland ever managed to defeat, and another epithet that could have been attached to his name was “Blunderer.”

His previous campaign in the Netherlands during 1745 had disclosed his almost total lack of military understanding. At the battle of Fontenoy (11th May 1745) he failed to reconnoitre the French position correctly, and was totally ignorant of the redoubts covering their left flank. He misused his cavalry and artillery, blamed his allies for not attacking more vigorously against prepared positions, and more by luck and the bravery of the Hanoverian and British battalions finally managed to penetrate the French centre which, in the end, was to prove just how bankrupt he was as a commander. Only the firm leadership shown by Sir John Ligonier and General Lord Crawford in extracting this massive pile-up of battalions in good order back to their own lines saved Cumberland from total ruin. [1]Whitworth, R. Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 103

Now once again in 1747, thanks in the main to his doting father, who still considered that his son was something of a military genius, the twenty-six year old Cumberland took command of the allied forces in the Netherlands. In January he and Ligonier, now promoted to General of Horse, were at The Hague making arrangements for the forthcoming campaign. Prince Waldeck was placed in charge of the Dutch contingent, while the Austrian troops came under the orders of old Marshal Batthyany. The Pragmatic Army also contained Hessians, Hanoverians and Bavarians, in all some 90,000 men and over 200 cannon. [2]Sources vary, ranging from as high as 100,000 to as low as 50,000. The actual figure for the allied troops engaged at Lauffeldt was approximately 60,000 of all arms.

The French army facing Cumberland’s motley band of mixed nationalities was at the peak of its strength and efficiency. Marshal de Saxe, the French commander, could put some 120,000 men in the field, supported by 300 cannon, the other armies of France having been stripped to a bare minimum in order that de Saxe could now administer a crushing victory. [3]As with the figures for the Allied troops mentioned above, the sources are conflicting in regard to the actual numbers engaged at Lauffeldt. Once again, taking a norm, the French army numbered … Continue reading The French held a line from Liége to Bruges.

Opening Moves.

In February 1747 Cumberland decided to break camp and move his army to threaten Antwerp. Unfortunately this plan backfired owing to lack of transport, and the allied army had to spend another two months in rough cantonments and foul weather around the town of Breda. Meanwhile the French army did not stir from their own warm winter quarters. For his part de Saxe wrote, ‘When the Duke of Cumberland has sufficiently weakened his army I shall teach him that a great general’s first duty is to provide for its welfare.’ [4]Quoted in, White, Jon Manchip. Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 208 Not only did Cumberland have difficulty finding suitable transportation, he, like the Duke of Marlborough before him, had problems with the Dutch who were becoming war-weary, and in particular with the Dutch general Waldeck, who proved to be unpopular even among his own men. [5]Ibid, page 209

Towards the end of April, while the allies were still debating their next move, de Saxe detached two flying columns from his main position. One column under Marshal Contrades took Liefkenhock and a fortress known as “The Pearl” just to the north of Antwerp, while the other column under Count Löwendahl seized Sas-van-Ghent, Ijzenijke and Eekels. [6]Ibid, page 209 By these rapid and timely manoeuvres, de Saxe had not only seriously compromised Cumberland’s communications to Willemstadt, he also caused such a panic across the whole of Holland as to force the Dutch to disregard any notion they may have had of discussing peace terms with the French. [7]Whitworth, R. Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 147

Now backed up by the firm resolve of the Dutch to continue the war, Cumberland once more moved to threaten Antwerp, which he hoped would force de Saxe into a general engagement. The French Marshal was too cool a customer to be drawn into making any false moves and held his main army behind the River Dyle close to the towns of Malines and Louvain, sending a strong detachment to bolster the garrison in Antwerp. Both commanders were well aware that the main prize was the city of Maastricht, the capture of which by the French would render the United Provinces untenable, and to this end de Saxe had already positioned a small army under Marshal Clermont on the Meuse River just to the south of Masstricht. Thus Cumberland had no choice other than to risk giving battle rather than allow Masstricht to be taken. [8]White, Jon Manchip. Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 210

Knowing full well that de Saxe would not attempt to attack the very strong fortifications of Masstricht until he was at full strength, Cumberland was posed with the problem of considering the possibility of Clermont’s small army being a decoy, and that as soon as the allied army moved against it, de Saxe would move swiftly to cross the frontier. Therefore the British commander was left with no other option but to conform with the movements made by de Saxe and the main French army.

In June, Clermont moved his forces towards the town of Tongres, while de Saxe pushed out detachments along the south bank of the River Demer. Cumberland interpreted these moves to mean that de Saxe and Clermont were about to unite their forces, and he therefore decided to crush Clermont’s army before this union could take place. Surrounding his march with great secrecy, Cumberland marched his army south. As soon as Clermont realised that he was about to be attacked by the allied main army he began to send frantic messages to de Saxe to come to his aid, and was seriously considering withdrawing his little army when a mud spattered and dishevelled de Saxe made his appearance in his camp. Calming Clermont’s fears, de Saxe gave orders for him to hold his position, telling him that not only was he about to be reinforced, but that the whole French army was marching to join him as he spoke. [9]White, Jon Manchip. Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 211

On the same day that Cumberland had begun to move his army against Clermont, de Saxe had ordered a parallel march by his own forces. This masterly stroke completely wrong-footed Cumberland who, arriving on the 30th of June, suddenly realised that instead of only having to deal with Clermont, he now had the whole united French army before him. Not only this but the French held the Heerderen heights overlooking the plain of Rosmeer from where they had a fine view of the allied columns as they arrived on the field. General Ligonier had the presence of mind to deploy the allied cavalry in a covering position across the plain, enabling the infantry to move into defensive positions stretching from the village of Bilsen on their right, to the hamlet of Wilre on the outskirts of Maastricht on their left. When he was satisfied that the infantry had reached their positions, Ligonier pulled back his cavalry by the left, withdrawing past the right flank of the British infantry who were holding the centre of the line, and forming up again in order of battle on the left wing just in front of the village of Kisselt. No attempt to disrupt the allied positioning was made by the French, although both sides carried out a brisk cannonade. [10]Whitworth, Rex. Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 149

Tactics and Formations.

Before proceeding with a description of the battle it is well worth pausing a moment to look at the various tactical changes that had taken place during the period from the end of the War of Spanish Succession until the outbreak of the War of Austrian Succession, and I give below the very detailed account of these formations taken from Brent Nosworthy’s excellent work, The Anatomy of Victory, Battle Tactics 1689-1763.

The British Infantry.

In 1745 Richard Kane published A New System of Military Discipline for the Battalion of Foot, which described much of the tactical systems then current in the British army. Interestingly enough, this is the same Richard Kane who was the acting commander of the Royal Irish regiment at the battle of Malplaquet 36 years earlier. This regiment’s use of the platoon firing system on this earlier occasion was immortalized in Robert Parker’s memoirs. (See Malplaquet article on this site)

The Firing technique and the method of advancing to the attack in the “new system” was probably very similar to that used during the War of Spanish Succession, as described by Captain Parker. The only notable change was the consistent use of the drum to supplement the colonel’s voice while issuing orders.

The men in a battalion were deployed just as thirty years earlier. A battalion of between 800 and 1,000 men was deployed in three ranks, the men having fixed bayonets onto the ends of their muskets. The grenadiers were placed on both flanks, while the officers were ranged in front of the battalion, the colonel in front, or in the absence of the colonel, the lieutenant colonel. The colonel, sword in hand, was on foot eight or ten paces in front of the men, in the centre of the battalion. He was accompanied by an “expert drummer” who stood beside him. The battalion continued to be divided into four “grand divisions,” each of four platoons. Counting the grenadier platoons this gave a total of 18 platoons, which were tolled off into three “firings,” each of six platoons.

The major difference between platoon firing as conducted near the turn of the eighteenth century and that 36 years later is the use of the drums to transmit orders. Richard Kane, who provides a very detailed account of platoon firing as it existed around 1745 advocated that the drum be used in addition to verbal commands. He argued that not every commander had a sufficiently loud and clear voice, and it detracted from the regiment’s self –image if the orders had to be given by the major or an adjutant during the actual battle. Also, it avoided the confusion that could arise during the heat of battle, if the commander was killed or otherwise incapacitated and a new voice was heard issuing orders. [11] What happened if the drummer(s) were killed is not mentioned!

When the battalion was in line, and the general action was about to begin, the colonel would order the drummer to make a ruffle. Then, positioned a distance in front of the battalion, he would deliver a short “cheerful” speech to encourage the men. Having finished speaking, the colonel would order the march and the drummers would beat to the march. He stood still until the battalion closed to four or five paces of him, then he turned around and slowly marched with the battalion towards the enemy.

The grand tactical theory behind the dynamics of the assault remained unchanged: the battalions were to engage the enemy in a series of firefights, at an ever-decreasing range, and break the enemy’s will to fight by a succession of ordered volleys. The advance was to continue until the enemy opposite the battalion began to fire, at which point the colonel ordered the drummers to stop. Turning to face his men once more, the colonel ordered the men to halt and the drummers to beat a “preparative.” As soon as this order was given, the men in the six platoons of the first firing, and all the men in the first rank (except those in the two centre platoons) were to prepare themselves to fire. The front rank knelt, and placed the butts of their muskets on the ground at their feet and angled their weapon upwards. This posture was assumed to defend themselves from cavalry. The men in the rear two ranks closed in on the front rank, and kept their thumbs on the cocks of their muskets taking care to keep their arms “well covered.”

…When the first firing was to fire, the colonel ordered the drummers to beat a “flam.” The men in the front rank dropped the muzzles of their muskets to the ground, while the two rear ranks presented their arms. The officers and subalterns in these platoons made certain that the muskets were levelled according to the range of the enemy so that the volley would have the best possible effect. At the same time, they had to caution their men to withhold their fire until the next orders on the drum.

As soon as the first firing was properly presented, the colonel ordered a second “flam” to be beaten, and the men fired their weapons. Immediately, these men recovered their weapons, fell back and started to load as fast as they could. The sergeant’s task at this point was to see that this reloading was done without hurry or disorder. The men in the first rank did not fire and were part of the battalion reserve fire. These men kept their muzzles on the ground and their thumbs on the cocks. The colonel then immediately ordered the drummers to beat the second “preparative,” and the platoons in the second firing prepared themselves to fire. The same set of orders and drumming was used to command this firing to fire.

When the second firing had fired, the same procedure was followed for the third firing. In theory, this routine was followed to produce a near-continuous fire, without significant hesitation between firings. If the need arose for the reserve to fire, the colonel ordered the first rank of all but the two centre platoons to present arms, and then the same set of commands was used as for the other firings.

If at any point during the firing the enemy started to retreat, the men were ordered to cease-fire. The next firing were to “half-cock” their weapons and be ready to fire later. The battalion was to march after the retreating enemy, rather than waste ammunition and time firing upon them. This was yet another reason why it was important for the colonel, as opposed to the captains, to control the firings. The firings would tend to continue for a much longer time when the captains controlled the firings of their individual platoons.

On the other hand, should the enemy infantry maintain their ground, the British battalion was to recommence its advance. Another “preparative” was beaten to order the next firing to make ready. Ordering the battalion to march, the colonel waited until the first rank was two paces from him before turning around and marching himself. The nearer a battalion approached the enemy, the closer he was to position himself near the first rank. This was important; otherwise he would stand out as an easy mark for enemy fire. When the battalion arrived at the appropriate distance away from the enemy holding its ground, the colonel was to order the battalion to halt. Immediately, the front rank knelt as before and the rear ranks closed forward. On the next “flam,” the next firing fired its muskets. The colonel now went through the same orders as before, making the various firings deliver their fire as quickly as possible until the enemy started to give ground.

Official doctrine purposely avoided prescribing what was to occur in the final moments of an encounter, where the threat of actual contact was imminent. This was left to the discretion of the battalion’s commanding officer. The one enjoinder was that should the enemy retreat faster than could be followed while still maintaining order, the infantry was to stop and continue firing until the enemy was out of range. The task of pursuit was left to the cavalry. [12]Nosworthy, Brent. The Anatomy of Victory, Battle Tactics 1689-1763, page 229-232

The British Cavalry.

Up until the first several campaigns of the Seven Years War, British cavalry doctrine had not significantly changed from that used during Marlborough’s time. The Duke of Cumberland’s instructions on how British dragoons were to conduct themselves during combat is illustrative of all British cavalry during this period.

When attacking, the dragoon regiment was to form a column of squadrons, each squadron deployed in two ranks. Prior to advancing, the men were ordered to draw their swords, then shorten their bridles, before bringing their swords to their thighs. Some of the officers and quartermasters in each troop did not participate in the charge but rode behind the squadron to rally anyone attempting to flee and bring them forward with the next squadron in the column.

The advance was begun at a walk or slow trot until the squadron had advanced to about sixty paces from the enemy. At this point, the squadron commander would order his men to “trot-out,” that is, ride forward now at a fast trot (canter).

As in Marlborough’s time, the emphasis was placed on maintaining strict order within the squadron formation. The troopers were to remain knee to knee throughout the charge. The next rank was to keep itself close enough to the first rank to push it toward the enemy, yet distant enough to avoid being stopped in its tracks if the first line was defeated.

The squadron commander if possible was to attempt to have the squadron advance obliquely to the right as it advanced, to be able to take a portion of the enemy line in flank as they met. In actuality, given the level of British cavalry training at this period, this proved difficult in practice and the two forces usually met head-on, if they actually closed to contact.

If the attack proved to be successful, the squadron was to halt at the position previously indicated for this purpose by the squadron commander. Here, it was to reorder itself to be able to respond to an enemy counter charge or wait to be supported by the squadrons following in column behind it. Should the first squadron’s charge be checked instead, its men were to ride to the left and right to clear the front so that the squadrons behind could continue the attack.

…The British cavalry lacked the thorough training and appears to have never have mastered the multiphased aspect of the Prussian (cavalry) charge at the gallop. British cavalry tended to charge enthusiastically without being able to maintain the tightness of formation….

…The Hanoverian cavalry appears to have been even more conservative, relying on the traditional advance at the trot and, the discharge of firearms prior to closing with the sword. One interesting feature of the Hanoverian cavalry charge was that the troopers in the third line (of the squadron) would “double,” that is, they would close into any space provided by the intervals between squadrons of files within the squadron to tighten up the formation…. [13]12 Nosworthy. Brent, The Anatomy of Victory, Battle Tactics 1689-1763, page 227-229

French Infantry tactics.

Although the years between the War of Spanish Succession and the War of Austrian Succession saw a proliferation of theoretical works about the need for new drills, exercises, manoeuvres and even tactics in the French army, very few changes were actually officially approved between 1713 and 1749.

Whatever changes were made can be summed up in a paragraph. By the outbreak of hostilities in 1740, the French infantry battalion now consistently deployed in four ranks. Previously, when a portion of each battalion had been armed with pikes, the company was nothing more than an administrative unit, without any tactical meaning at all. However, once all of the men within the battalion started to be armed identically, the company began to be treated as a tactical subdivision of the battalion. The training camp of 1733 officially recognized this development; henceforth a company was referred to as a “section” in this capacity.

However, the battalions continued to be arranged in the same fashion; the officers and subalterns were positioned according to the regulations of 1703, while the distance between the ranks and the files remained unchanged. Unfortunately, the highly cumbersome and time-consuming methods of deploying from column into line from line into column also remained virtually the same, although there was no lack of unofficial experimentation by the more enterprising regimental commanders.

In terms of fire systems, the only progress that could be pointed to was that the French troops no longer performed the caracole version of fire by ranks. Prior to 1749-1750 there was never any official mention of either cadence marching or a cadence manual of arms (loading and presenting the weapons). The troops were still forced to march with open ranks (six paces between ranks), and had to close ranks before they either changed direction of march or deployed.

The conservatism within the French army ran deep, that despite Puységur’s constant lobbying for the use of continuous lines of infantry, en muraille, the battalion along each line officially were still to be deployed with a full interval separating them and their neighbour as late as 1750, despite the fact that, practically speaking, this method of deployment was abandoned during the War of Spanish Succession! Fortunately for the French, this last regulation appears to have been rarely, if ever, carried out during this era, there usually being too many battalions to deploy across the battlefield to permit such wide intervals. [14]13 Nosworthy. Brent, The Anatomy of Victory, Battle Tactics 1689-1763, page 199-200

French cavalry tactics.

By the 1730’s and 1740’s the French had become more aware of the value of shock and the role of speed in winning close order combats. In his Reveries De Saxe stated, “Such that cannot go at speed over a couple of thousand yards to pounce upon the foe, is for nothing in the field.” However, Colonel Mack’s comments that Austrian cavalry could not gallop 50 yards without 25 per cent of the horses becoming disordered were probably as applicable to French cavalry.

At the Battle of Fontenoy (1745), Marshal de Saxe ordered his cavalry to break the British infantry column that had advanced behind the French lines, using the “breast of their horses.” Of course, given the sharp rows of enemy bayonets, cavalrymen never found this an easy task.

The debate over whether firearms should be used by cavalry started to slacken; with most cavalry officers believing they should never be used during a battle when meeting their enemy counterpart. According to Grandmaison:

“A horseman should never use his pistols but on the most pressing occasions, either to save his life, or disengage himself from some disagreeable situation.”

The French continued to believe that cavalry capability against infantry and other cavalry was largely the result of “weight of horse.” When attacking enemy infantry, French cavalry used a different set of tactics. Previously, French cavalry had used pistol or carbine fire when attacking formed infantry. However, the success of this method declined with the adoption of the socket bayonet. Also, any attempt to have an entire line of cavalry close with a line of infantry, necessarily resulted in extensive casualties because of the number of men exposed to musket fire. These considerations, as well as exposure to new methods used by Austrian light cavalry during the first two campaigns of the War of Austrian Succession, led the French to develop new cavalry tactics during the mid-1740’s.

These newer tactics were based on the principle that a few brave and experienced men would create the necessary gaps in the enemy infantry’s line, and then the remainder of the squadron would exploit these. The fewer numbers of men initially exposed to enemy fire would mean correspondingly fewer casualties. Each squadron leader commanding experienced troopers would have 15-20 of his bravest men, presumably his “commanded” men positioned on each flank of the squadron, attack the infantry in line while the remainder of the squadron advanced in an orderly fashion behind them. His first wave advanced at the trot until 20 paces or so away from the line then moved in at the gallop.

The concentration of muskets directed against this handful of horsemen was such that most, if not all, would be hit by the resulting fusillades. However, it was an accepted cavalry maxim that only 50 per cent of the horses and men hit by musket fire would be disabled, and, in fact, if the attacking cavalry was sufficiently close when fired upon, the remainder generally redoubled their efforts upon being hit. This interesting observation was made by General Grandmaison of the Volontaires des Flandres:

“ The other half [of those hit by gunfire] animated by the fire and the blood, fall with fury and impetuosity on the infantry, whose breastworks of bayonets is not able to sustain the weight of the horses in fury. The rider cannot any longer command them, they rush headlong, and make openings for the rest of the squadron, to penetrate and break the battalion, which cannot oppose this shock, a manoeuvre sufficiently quick and exact.”

It had long been known that horses would not voluntarily impale themselves upon the hedge of bayonets offered by an ordered line or a square. The above strategy was to position the attacking cavalry close to the line or square being attacked at the moment of fire, so that the horses infuriated by the pain of their injuries, especially those in the chest, would forget the danger of the bayonets and in their agony involuntarily move onto the infantry they were attacking.

If any gaps were created in the line of infantry, the remainder of the squadron still in good order would attack the line. It should be pointed out, however, that this attack could be delivered at a trot at the quickest, since the squadron would have been 20-30 paces behind the leading elements. It was hoped that the first group of attackers would, contrary to the wishes of the enemy officers, succeed in drawing the fire of all the enemy ranks. Then when the main body of horsemen closed, the infantry would be caught without fire. The cavalry, under these circumstances, could advance to contact much more easily, and the infantry were much more inclined to break.

Unfortunately for the French, there was a downside to these tactics. Although they fulfilled their purpose of reducing the number of casualties incurred in any localized attack, by their very nature they tended to work against massive attacks, conducted in unison, against large enemy formations.

The ineffectiveness of piecemeal charges conducted with limited forces was demonstrated clearly at Fontenoy, where a number of French cavalry regiments were thrown one at a time against the British (and Hanoverian) column that succeeded in penetrating the French line between the redoubts in the Wood of Barry and that of Fontenoy. Only the assault led by De Vignecourt had any success. This officer and 14 men managed to momentarily break through the enemy formation but were immediately killed or wounded. All these attacks, made without any initial preparation or agreement and made with limited forces, were defeated by the compactness of the British formation and the steadiness and discipline of the British platoon fire. [15]14 Nosworthy. Brent, The Anatomy of Victory, Battle Tactics 1689-1763, page 216-220

The Battlefield.

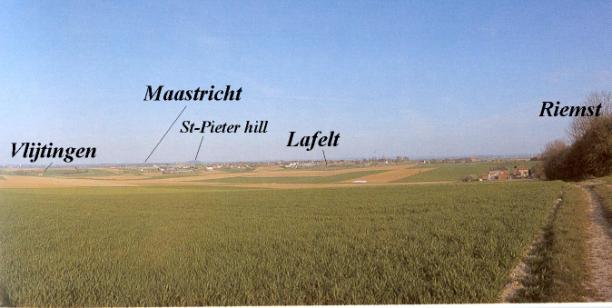

The position taken up by the allies on that dull and rainy morning of July 2nd 1747 was some four miles in length incorporating several villages dotted across the undulating plain. Much of the land was cultivated, and many of the farms and houses were surrounded by orchards and gardens, which were, in turn, surrounded by embankments in the event of flooding. On the right flank the Austrians under Marshal Batthyany held the villages of Grosse and Kleine Spauwe. Their position was almost unassailable to a direct frontal attack as it was protected by a steep sided ravine. On the Austrian left stood the Dutch troops under Waldeck, they also had units covering some of the approaches to Grosse Spauwe. To the left again stood the British, Hanoverian, Hessians and Bavarian infantry. The British Guards were detailed to hold the village of Vlytingen, while a mixed force of British and Hessians held Lauffeldt. Cumberland did not hold these villages in any strength, nor did he order the clearing of pathways through the hedges to facilitate bringing up reinforcements. The Allied commander chose to draw-up his infantry in the traditional manor, forming them in line behind the villages in the open plain. General Ligonier’s cavalry, as mentioned earlier, was positioned to the left rear of Lauffeldt, his line continuing to and around the village of Kisselt. [16]Whitworth. Rex, Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 150

The Battle.

Well before the commencement of the battle General Ligonier had been trying to persuade Cumberland to hold the advanced villages in more strength and, ‘…Cumberland’s inadequacy as a general was never better illustrated than by his original intention to ignore the existence of these natural bastions, and to range his army on the bare plain behind them in a single fighting line…. [17]White. Jon Manchip, Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 212 It was only by his perpetual pestering that Ligonier finally managed to make Cumberland understand that the best way of blunting any French attack was to break it up by using the villages as military bulwarks, rather like a breakwater on the seashore. It was after all Ligonier who had seen what strongly held villages were capable of doing to attacking formations after his experience at the battle of Fontenoy. However Cumberland still vacillated to such an extent that the villages of Lauffeldt and Wiltingen were first occupied in great strength, then evacuated, reoccupied again, and once more evacuated before being finally occupied for a third time! [18]White, Jon Manchip, Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 212 This indecisiveness shows Cumberland’s total lack of ability, and total ignorance of any real military knowledge. The final order to reoccupy the villages came only an hour before the French began their assault, and gave scant time for the men to put the houses and farms into a state of defensibility. During the confusion Cumberland had also sent orders that the villages should be destroyed, and was unable to countermand these instructions before some of the buildings were set on fire. Thus, not only were the defenders hard pressed to secure the villages against attack, they were also now partially blinded and suffocated by thick clouds of smoke. [19]Ibid, page 212

From his vantage point on the Heerderen heights, de Saxe had been scanning the field through his telescope since 6 am in the morning. A heavy rain was now falling, and this coupled with the smoke and the perpetual movements of the allied infantry to and from the villages caused de Saxe some anxiety. The French king, Louis XV, had joined his troops to be present at the battle and he concurred with de Saxe that either Cumberland was trying to confuse them as to his true intent by all these convoluted movements, or that the allied commander was in such a state of uncertainty that he may even be considering quitting the field and placing his army under the guns of Masstricht, and as the Marquis de Valfrons informs us, ‘For more than two hours, the Marshal believed that the enemy was manoeuvring to recross the (River) Meuse; he was confirmed in his opinion when he saw that Laffeldt was on fire.’ [20]Valfrons, Charles Methei Marquis de, Mémoires (ed Maurin) (1906), page 206 Therefore the French Marshal was only too happy to help Cumberland speed his withdrawal.

To this end de Saxe compiled his battle plan. After sending forward an armed reconnaissance of nine battalions, he would launch an overwhelming attack using the mass of his infantry in brigades, one behind the other against the allied left centre at Lauffeldt. Simultaneously an outflanking move by the French cavalry would take place against the allied left flank around the village of Wilre in order to place themselves between the Maastricht and Cumberland’s retiring columns. Under this erroneous assumption de Saxe ordered forward Clermont’s grenadiers, supporting them with a further two brigades of infantry. These troops came on in fine style, drums beating and standards slapping soggily around their staffs expecting to receive nothing more than a sporadic fire from their supposedly retiring foes. The reception they actually got came as quite a shock, for as well as the disciplined platoon firing and rolling volleys, which carpeted the plain with many white uniforms, Ligonier had also had the presence of mind to push forward a battery of artillery which was sited with such skill that its fire ploughed long lanes through the advancing French masses.

Much to de Saxe’s chagrin he now realised that his enemy apparently had no intention of retiring but was now committed to holding their ground and making the French pay dearly in trying to gain it. While de Saxe pondered the situation Valfrons rode up to him and offered some words of comfort and encouragement, ‘Marshal, you beat them at Fontenoy, when you where dying. You beat them at Rocoux when you were still a sick man. Today you will slaughter them!’ [21]Quoted in Jon Manchip White, Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 214

The redoubtable Marshal soon shook off his disappointment at having his plans scupperd by Cumberland’s unintentional ruse de guerre and set about altering his battle plan back to their original form. He had, after all, expected that the villages would be occupied in the first place, and as this was now the case then all that he need prove was; ‘…he still had faith in his own dispositions.’ [22]Ibid, page 214 As the shattered remains of his grenadiers fell back from Lauffeldt, de Saxe ordered Clermont to form a new attacking column and take the village. He also sent the Marquis de Saliéres with another massive infantry force against Wiltingen.

The battle for the two villages was a murderous affair. The French Marshal’s determination to break through the allied centre was met by the equally determined resolve of the Landgrave, Frederick II of Hesse-Cassel, who commanded the German and British infantry in this sector, to show him just how futile this would prove against his stalwart battalions. The fighting went on for four hours with the French forcing their antagonists out of the villages four times, only to be evicted on each occasion at the point of the bayonet. For once, showing a spark of military intelligence, Cumberland kept his fighting troops supplied with a constant flow of reinforcements from his second line, and he even ordered nine battalions of Austrian infantry over from his right flank in preparation for a general advance which he felt sure would unhinge the by now, disorganised French masses in the centre. [23]Whitworth, Rex, Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 153

Indeed de Saxe had already paid a heavy price attempting to secure the two villages and could do little else other than raise the stakes even further. As Clermont’s shattered battalions recoiled for the forth time, de Saxe sent forward the regiments of La Fére, Ségur, Bourbon, Bettens, Monnin, Monaco, Royal Marine, Vaisseaux and d’Aubeterre, together with the fighting Irish regiments of the “Wild Geese.” These tried and true veterans move forward in magnificent order, only to be cut down in windrows by the terrible hail of lead and iron sweeping the approaches to Lauffeldt and Wiltingen. The chevalier Dillon, commanding the gallant Irish brigade was mortally wounded and taken prisoner, while the Comte d’Aubeterre fell, together with twenty-two of his officers and scores of his men within the smouldering ruins.

After committing forty battalions to the bloodbath, de Saxe was still no closer to breaking the allied line, but it was far too late now to consider any alternative plan other then the one he had set in motion. After watching the destructive fire from a thirty-gun battery which had been suddenly unmasked by the allies, and which tore great gaps through the cavalry lines of the Régiment du roi, which had been drawn up in support of the infantry, de Saxe threw any restraint he may have still harboured to the winds. Unsheathing his sword he now ordered the Marquis de Saliéres forward to take Lauffeldt with twelve fresh battalions.

Once again the French infantry came under a tremendous blizzard of fire, but a lodgement was finally made in Lauffeldt. Pressure was also beginning to tell in Wiltingen, where the allied infantry were slowly being forced back house-by-house. Seeing the chance of slicing through the enemy centre at last, de Saxe charged towards Wiltingen with a mass of cavalry. It was at this point that Cumberland himself was considering going over to the offensive, however the advancing squadrons of French horsemen had to be dealt with first. Ordering forward his Dutch cavalry, Cumberland fully expected to be able to contain de Saxe’s sudden impetuosity and throw his whole attack back in disorder. Things were not to be however. The Dutch cavalry were seized by panic at the approach of the French, and turning their horses about began to quit the field. As if this were not bad enough, their flight took them directly into the lines of their own infantry stationed behind. Utter confusion now prevailed, with foot and horse trying desperately to untangle themselves while being hacked at by the triumphant French cavalry. The most vulnerable section of the allied position was at last falling apart, and the French infantry now began to move forward to exploit the gap. [24]White, Jon Manchip, Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 216 As if to compound his woes, Cumberland now received news that the French had taken the village of Wilre on his right flank, and that squadron upon squadron of their cavalry were about to charge this part of the allied line.

On this part of the field General Ligonier had been studying the gathering host of French horsemen, but was still unaware of the disaster that had befallen the allied centre. As a professional cavalryman himself he fully appreciated the fact that a full-blown cavalry encounter was in the offing and, ‘Tempted by the occasion at last offered of opposing our cavalry in the plain to that of the enemy he gave orders to advance upon them.’ [25]Quoted in, Whitworth, Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 153

‘Ligonier’s Charge’ has been passed down as one of the most outstanding exploits of the British Army, and was one of the greatest cavalry encounters in military history. The encounter involved some sixty allied squadrons attacking one hundred and forty of the enemy, throwing the latter back in such disorder that five French standards were captured and the village of Wilre was retaken. The charge also allowed a breathing space for the allied infantry in the centre to regroup and begin to fall-back in good order. Although the issue of the battle had now been decided firmly in favour of the French, Ligonier was still ready to get in amongst their squadrons yet again while they were still reeling from the effects of his first charge. As he was regrouping his forces for the next round a messenger galloped up bearing orders from Cumberland to cease any further attacks as Lauffeldt was now in enemy hands. The allied commander’s message also contained strict instructions that any unauthorised moves by Ligonier would have to be accounted for after the battle. [26]White, Jon Manchip, Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 217

Ligonier immediately sent back a note informing Cumberland that, in his opinion, one more charge by the cavalry could well restore the situation for the allies, however the time taken to find Cumberland and for him to grudgingly give permission for a second charge worked in de Saxe’s favour and allowed him time to restore order in his lines.

With the French squadrons now regrouped, Ligonier was well aware that de Saxe would now attempt to clear a path through the allied cavalry screen and get in amongst the confused ranks of infantry struggling in their rear. Whether or not Cumberland would make him face a court martial for disobeying orders, Ligonier considered that he had to sacrifice his squadrons to save the infantry. [27]Ibid, page 217 Drawing up the Royal North British Dragoons, the Inniskillings Dragoons and the Duke of Cumberland’s Hussars, Ligonier threw them head on into the mass of French cavalry. The shock of their impact was so great that the British horsemen broke clean through the bewildered enemy formations scattering them right and left. This penetration was to prove not only glorious, but also fatal to the now reduced British squadrons. Behind his cavalry,de Saxe had positioned several battalions of infantry and these, together with the arrival of fresh French cavalry upon their flanks, decimated Ligonier’s already depleted ranks. The General himself was surrounded while trying to bring forward some Hessian cavalry to help extricate his horsemen, and by some quick thinking on his part he suddenly cried to the French troopers to ‘Halt,’ stating in his native tongue that they were to turn and concentrate on another part of the battlefield. [28]Whitworth, Rex, Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 155 Unfortunately for Ligonier he was recognised as an important enemy officer by the Star of the Order of the Bath, which he wore on his uniform. Offering his captives his watch and his purse, which were refused, his sword was then taken and he was led off the field to be presented as a prisoner before the French King. [29]Ibid, page 155

Ligonier’s charge had cost the British cavalry dearly, but it had stalled de Saxe’s plans sufficiently to allow time for Marshal Batthyany to bring across the rest of his Austrian infantry, thus placing a strong defensive screen between the French and the retreating allied formations, allowing them time to march off the battlefield.

White tells us that, ‘Valfrons- at heart, alas! something of a lickspittle- censures Maurice (de Saxe), in his memoirs, for his conduct of the pursuit after Lauffeldt. He asserts that when, at Wiltingen, the Dutch cavalry broke, Maurice could have started the route by sending in Clermont-Tonnerre and his dragoons. ‘He thus proved to me,’ Valfrons says, ‘that since he did not wish to end the war, he could only half win the battle.’

White goes on to say this charge was frequently levelled at de Saxe but ‘…is surely nonsense. There would seem to have been little doubt that, at least on this occasion, Maurice strained every nerve to destroy the beaten enemy army. He knew that his failure to do so would have serious personal and political consequences. But what more could he have done? His right wing had been disorganised by Ligonier’s attacks: the Austrians had strongly and suddenly intervened after the battle had already been raging for a full six hours; the rain was still pouring down; the battlefield had been churned into mud; and smoke was billowing thickly across the landscape from the batteries and the burning villages.’ [30]White, Jon Manchip, Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 218

With the above being said, it would seem that Cumberland did indeed have a lucky escape, which throws still more light on the fact that he was not a competent commander. The result of the battle, and his conduct during its course, should in no way detract from the fact that the allied troops, given their proper placement at the commencement of the battle could, under more resolute leadership, have seriously compromised the whole of de Saxe’s plans.

The cost on all sides had been considerable. Over 2,000 British casualties, 2,500 Hanoverian and almost 2,000 from the other allied contingents. The victorious French had paid an even greater price in killed and wounded, totalling 14,000 men.

The battle had cost a good deal of blood. Never was anything more horrible seen. The plains and villages all around were covered with dead and wounded men. The loss on this day, on one side and the other, amounted to more than 20,000 men killed, wounded or taken prisoner. [31]History of Maurice Count Saxe, The. By an officer of Distinction. Translated from the French. (1753). (N.b.This is a translation of the book by Néel, vide infra.

Even after his appalling display at Lauffeldt, Cumberland was once again given the command of the Hanoverian Army during the Seven Years War (1756-1763). He was defeated by the French at the Battle of Hastenbeck (July 1757), and thereafter put his name to the Convention of Klosterzeven (September 1757) in which he promised to evacuate Hanover. This was the final straw for George II who immediately repudiated the terms of the convention and dismissed his son from command of the army. It has been said that Cumberland was a good administrator but a bully and a martinet. This being so, perhaps his true vocation was as the leader of a press-gang rounding up unwilling recruits from the taverns of England?

Graham J. Morris.

September 2004

The Battlefield Today

Although I have only passed the battlefield of Lauffeldt while travelling to other destinations, I have enclosed some excellent photographs of the site taken by a friend of mine, Ugo Janssens. Also I am indebted to my friend Alain Tripnaux for supplying some of the prints and drawings of French uniforms. Alain is a very busy chap at the moment dealing with the preparations for next years Fontenoy celebrations but, like Ugo and his partner Esther, nothing is ever too much trouble-thanks guy’s!

Bibliography

| Nosworthy, Brent. | The Anatomy of Victory, Battle Tactics 1689-1763. (Paperback edition), New York 1992 |

| White, Jon Manchip. | Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, Rand McNally and Co, London 1962 |

| Whitworth, Rex. | Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, Oxford University Press, 1958 |

| Valfrons, Charles Mathei de. | Mémoires (ed. Maurin) (1906) |

Further Reading

| Saxe, Maurice comte de. | Mes Réveries, or Memoirs upon the Art of War, by Field Marshal Count Saxe, Translated from the French (London, 1757). |

| Townshend, C.V.F. | The Military Life of Field Marshal George, First Marquess Townnshend. (1901) |

The spelling of the village which gave its name to the battle is variously given as, Lafeldt, Lewfelt, Lawfeld, Laufeldt and Lauffeldt. I have chosen the latter after being informed that it is more appropriate to other nationalities.

References

| ↑1 | Whitworth, R. Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 103 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Sources vary, ranging from as high as 100,000 to as low as 50,000. The actual figure for the allied troops engaged at Lauffeldt was approximately 60,000 of all arms. |

| ↑3 | As with the figures for the Allied troops mentioned above, the sources are conflicting in regard to the actual numbers engaged at Lauffeldt. Once again, taking a norm, the French army numbered approximately 90,000 of all arms on the battlefield. |

| ↑4 | Quoted in, White, Jon Manchip. Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 208 |

| ↑5, ↑6 | Ibid, page 209 |

| ↑7 | Whitworth, R. Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 147 |

| ↑8 | White, Jon Manchip. Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 210 |

| ↑9 | White, Jon Manchip. Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 211 |

| ↑10 | Whitworth, Rex. Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 149 |

| ↑11 | What happened if the drummer(s) were killed is not mentioned! |

| ↑12 | Nosworthy, Brent. The Anatomy of Victory, Battle Tactics 1689-1763, page 229-232 |

| ↑13 | 12 Nosworthy. Brent, The Anatomy of Victory, Battle Tactics 1689-1763, page 227-229 |

| ↑14 | 13 Nosworthy. Brent, The Anatomy of Victory, Battle Tactics 1689-1763, page 199-200 |

| ↑15 | 14 Nosworthy. Brent, The Anatomy of Victory, Battle Tactics 1689-1763, page 216-220 |

| ↑16 | Whitworth. Rex, Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 150 |

| ↑17 | White. Jon Manchip, Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 212 |

| ↑18 | White, Jon Manchip, Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 212 |

| ↑19 | Ibid, page 212 |

| ↑20 | Valfrons, Charles Methei Marquis de, Mémoires (ed Maurin) (1906), page 206 |

| ↑21 | Quoted in Jon Manchip White, Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 214 |

| ↑22 | Ibid, page 214 |

| ↑23 | Whitworth, Rex, Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 153 |

| ↑24 | White, Jon Manchip, Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 216 |

| ↑25 | Quoted in, Whitworth, Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 153 |

| ↑26 | White, Jon Manchip, Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 217 |

| ↑27 | Ibid, page 217 |

| ↑28 | Whitworth, Rex, Field Marshal Lord Ligonier, page 155 |

| ↑29 | Ibid, page 155 |

| ↑30 | White, Jon Manchip, Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice de Saxe, page 218 |

| ↑31 | History of Maurice Count Saxe, The. By an officer of Distinction. Translated from the French. (1753). (N.b.This is a translation of the book by Néel, vide infra. |

Nice account. I remember, 30+ years ago, coming across a contemporary document about Ligonier’s charge at Lauffeldt. It gave the strength of the Greys and Inniskillings as three squadrons each, and the Duke of Cumberland’s Dragoons (not Hussars, they were the re-mustered Kingston’s Light Horse of Culloden fame) as two squadrons. Each squadron was about 150 officers and men- so a bit bigger than earlier in the war, as a result of drafts from units at home. I noted that the Greys lost 158 men, the Skins 117, and the Duke’s 81, which were very heavy losses for cavalry regiments in a single battle. I think only Bland’s Dragoons and Ligonier’s Horse at Dettingen had comparable loss rates. Unfortunately, I can’t find my original notes, which had the PRO reference- but I share that info FWIW.

Interesting comments on Ligonier’s cavalry charge at Laffeldt Gyln. Sixty allied squadrons attacked 140 French squadrons with such vigour that they were thrown into complete disorder. The village of Wilre was retaken, and five French standards taken. Unfortunately, Ligonier was ordered not to press his attacks by orders from Cumberland, who considered the battle lost. One wonders what the outcome of another charge by the allied cavalry would have achieved?

Thank you for visiting the site, and if you do find your lost note’s I would very much like to read them.

Best regards,

Graham

Hi Graham,

Many thanks for this valuable information. We hope to be visiting the a week tomorrow, really appreciate your help.

Kind regards,

Martin

Have a great trip Martin. Let me know if any fresh battlefield relics have been found.

I will keep in touch and let you know when my Canadian friend, Paul, who accompanied me on my visit to Lauffeldt, has published his book dealing with the battle.

Best regards,

Graham

Thank you for visiting the site Martin.

Take the road to Vlitingen out of Lauffeldt village. You will soon come to a low cut box hedge surrounded by trees. The Celtic Cross and a modern battlefield monument are situated there.

Try and get to the high ground at Herderen for a good view across the whole battlefield. This was the place where de Saxe and the French King viewed the battle. The one big problem is where Cumberland was during the fighting?

Best Regards,

Graham J. Morris

Dear Sirs, thank you for this fascinaating insight. I would like to visit the battlefield in September, two weeks time, could you please advise where the celtic cross is located?

Thank you,

Martin