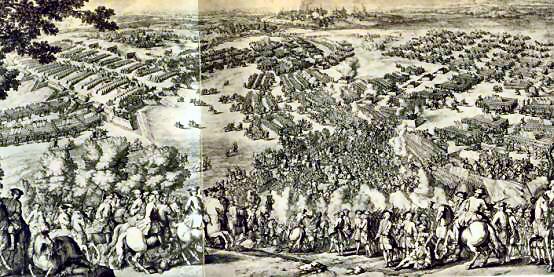

28th June 1709

by Denis Martens the Younger painted 1726

“Dread Poltowa’s day,

When fortune left the royal Swede,

Around a slaughtered army lay,

No more to combat and to bleed,

The power and fortune of the War

Had passed to the triumphant Czar.”

(George Gordon, Lord Byron) [1]Quoted in Sir Edward Creasy’s, The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World, page 270

Introduction.

The Swedish Empire, although not comparable with the huge areas and populations that we today associate with such empires as Rome, the Mongols or the Russian and British, was nevertheless a formidable force to be reckoned with during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Her rise to the imperium can be traced back to the middle of the sixteenth century when, along with Russia, Poland and Denmark, Sweden also took advantage of the vacuum in the Baltic created after the collapse of the Teutonic Knights. [2]Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 29 The power struggle that resulted netted Sweden Livonia from Poland, West Pomerania and some of East Pomerania, Bremen, Verden and Wismar. She acquired Halland, Jämtland, Härjedalen and the Gotland and Ösel islands from Denmark, together with Skåne, Bohuslän and Blekinge, while Russia ceded Ingria and Lexholm, which effectively cut her off from the Baltic Sea. [3]Ibid, page 30

By 1697 it had become obvious that the Danes were not prepared to take all of this land – grabbing lying down, nor for that matter would the newly elected King of Poland, Frederick Augustus II, Elector of Saxony be happy until Swedish influence had been removed and Polish land reclaimed, while the giant and far – seeing Tsar Peter I was eager to obtain a Baltic port for Russia’s burgeoning trade and was fully committed to drag his country kicking and screaming into becoming a modern state equal to any of her European neighbours.

In one way the Great Northern War may be said to have been sparked off by Swedish greed and jealousies working from within. In 1680 their King, Charles XI, realizing that the aristocracy had been steadily increasing its power and influence since the death of Gustavus Adolphus, which in turn was alienating the other classes in Swedish society, introduced the “Reduction” policy. This entailed the return of vast estates to the crown, which had been placed under the Swedish nobles for them to administer, and which many had begun to consider as being part of their own hereditary lands. [4]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 295 Among these disillusioned nobles was a Livonian, John Reinhold Patkul who, having had his lands taken from him, offered his services to Frederick Augustus whom, in 1698, he persuaded into forming a coalition with Russia and Denmark against the Swedes. [5]General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II page 162 With the death of Charles XI on April 5th 1697, and the ascension of his fourteen-year-old son, Charles XII to the Swedish throne, the time did indeed seemed propitious to take action.

In March 1698 Denmark and Saxony put their respective signatures to a defensive alliance, and in July the Russian Tsar Peter joined Augustus at Rawa to consider an anti-Swedish alliance, which was discussed while downing copious quantities of wine and vodka. [6]Robert I. Frost, The Northern Wars 1558-1721, page 228 In 1699 Peter signed a defensive agreement with the Danes, while in September of that year he had another meeting with Augustus at Preobrazhenskoe at which he set out his plans for an attack against the Swedish province of Ingria, to take place in the spring of 1700. For their part the Danes would move against Schleswig and Holstein, while Augustus’s Saxons army would strike at Livonia. An abortive attempt by the Saxons to take Riga in December 1699 failed, but they managed to push troops across the Dvina River early in 1700 and took the town of Dünamunde in March. Meanwhile the Danes had entered Holstein-Gottorp laying siege to Tønning. The Russians were a little late off the mark, but once Peter had concluded his peace treaty with the Turks in August 1700, his army began to move. [7]Ibid, page 228

Charles XII

Born on the 17th June 1682, Charles was a skinny and rather frail child, however when he was only four years old he was riding out with his father and taking part in tough masculine pursuits. [8]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 312 When he was eleven years of age his mother, Queen Ulrika Eleonora died. The young Prince came down with smallpox soon after, which left his face pock-marked, but his mothers death caused a closer relationship to develop between Charles and his father who, after his wife’s demise spent much more time with his children; this, in turn affecting the boy’s mannerisms, “… his speech became brief, dry and understated, saved from being hopelessly cryptic by occasional glimmers of sympathy and wit. Honour and sanctity of one’s word became his two cardinal principles: A king must put justice and honour ahead of everything; once given, his word must be kept.” [9]Ibid, page 312-313

With the death of his father in 1697 Charles, being only fourteen years of age, came under a council of Regents who took control of running Swedish affairs. This proved impractical as the members of the Regency Council seldom agreed on policy, and realising that Charles was not the kind of prince to be pushed into the background, he was declared king in November, then aged only fifteen. His coronation was something of a fiasco, with the entire entourage being ordered to wear black in memory of the old king; the crown fell off Charles’s head while he was mounting his horse, the archbishop dropped the anointing oil, Charles refused to give the traditional royal oath. Finally, taking the crown, he placed it upon his own head. [10]Ibid, page 314

Sketch of Charles on campaign

A very colourful view of Charles’s character and make up is given by General Fuller:

‘…Charles was knight errant and berserker in one. He lived for war, loved its hardships and adventures even more than victory itself, and the more impossible the odds against him, the more eagerly he accepted them. Wrapped in an impenetrable reserve, his faith in himself was boundless, and his power of self-deception unlimited- nothing seemed to him to be beyond his reach. The numerical superiority of his enemy; the strength of his position; the weariness of his troops; their lack of armament or supplies; foundering roads, mud, rain, frost and scorching sun appeared to him but obstacles set in his path by Providence to test his genius. Nothing perturbed him, every danger and hazard beckoned him on. High-spirited, but always under self-control, faithful to his word and a considerate disciplinarian, from the moment he took the field he became a legend to his men, un étandard vivant which endowed them with a faith in his leadership that has never been surpassed. His fearlessness was phenomenal, his energy prodigious, and added to these qualities he possessed so quick a tactical eye that one glance was sufficient to reveal to him the weakest point in his enemy’s line or position, which at once he attacked like a thunderbolt. Such was the boy king whose Baltic provinces the self-indulgent Augustus and the boorish Peter over their wine-cups had decided to filch and divide between themselves.’ [11]General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol II, page 164-165 . The treaty had been drawn up in 1697. By its terms Sweden promised to back the Maritime Powers against Louise … Continue reading

The Road to Glory and Destruction.

If the three allied powers harboured any thoughts of a rapid and decisive campaign they were soon disillusioned. Even as Peter declared war on Sweden in August 1700, and while the Saxons settled down once again to lay siege to Riga, Denmark had been knocked out of the war. Calling for help from the Anglo-Dutch, which had been agreed upon in the terms of the Treaty of Rijswick, and the Altona agreement* the Swedish fleet made a bold move along the Swedish coast, evading the Danish fleet and joining up with an Anglo-Dutch squadron which enabled them to land 10,000 troops on Zealand, from where they marched on Copenhagen. Faced by the possibility of a blockade of his capital, and being pressurised by the Maritime Powers, the Danish king, Frederik IV withdrew from the war. [12]Robert I. Frost, The Northern Wars 1558-1721, page 229

After dealing with the Danes, Charles wasted no time, and in October 1700 he marched east intending to relieve Riga. However news soon reached him that the Russians had invested the fortress town of Narva in Estonia, and he immediately turned north, halting at Wernburg until 13th November in order to collect his army. [13]General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol II, page 165

With only 10,500 men Charles struck out for Narva. The roads were all but washed out due to the autumn rains, and Russian cavalry had devastated the countryside. Food and fodder were scarce, with the troops being forced to rely on only what they carried in their packs. [14]Robert Massie, Peter the Great, page 327 After four days of marching the Swedes came upon 5,000 Russian cavalry guarding the exit from the Pyhäjöggi Pass, eighteen miles west of Narva. Charles immediately ordered forward some 400 of his foot Guard, together with his own small escort of dragoons and eight cannon. Stunned at the rapidity of the Swedish attack the Russians retired, but were not routed, their commander, Field Marshal Count Boris Sheremetev having orders to only observe the enemy movements and not to engage their main field army in any major action. [15]Ibid, page 328

Tsar Peter the Great

The sudden appearance of the Swedish army near Narva, according to General Fuller, caused Peter to panic and abandon his troops. [16]General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol II, page 165 This seems a little harsh. Peter had no reason to believe that Charles would not conform with the excepted principles of warfare of the day, and that the Swedes would take their time in planning any attack against the Russian lines of contravallation which were defended by over 40,000 Russian regular and militia troops supported by 140 cannon. Also Peter was anxious to meet up with Augustus and find out why the Saxons had once more abandoned the siege of Riga. These facts, plus the overriding responsibilities of being the sole arbiter of Russian policy determined Peter’s actions. If we wish to find fault with anything then it lies with his choice of the man whom he placed in command at Narva when he departed- Charles Eugéne, Duc du Croy. Du Croy spoke hardly any Russian and was not familiar with the other officers. He was also much concerned in regard to the length of the Russian position, which he considered to be far too long and could easily allow the Swedes to penetrate at one point before troops could be pulled from other parts of the line to block them. [17]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 329

Du Croy’s worst fears were to be realised when, at around 10 a.m. on the morning of the 20th November the Swedish army began to appear along the tree-covered slopes of the Hermansberg ridge. Although outnumbered by almost four to one Charles launched his infantry directly at the Russian lines. Under cover of a fortuitous snowstorm the Swedes swept forward piercing the defences in two places, putting the Russians to flight. In all they lost some 8,000 killed and wounded, together with thousands of prisoners, all of whom, with the exception of the officers were set free, the Swedes having no facilities for handling such numbers. Swedish casualties were fewer than 2,000 – the making of a legend had begun.

The Swedish army went into winter quarters around Dorpat after its victory at Narva, Charles intending to deal with Augustus in the spring of 1701. For his part the Polish king found no real enthusiasm for war among his Commonwealth subjects and many among the nobles favoured an alliance with Sweden against Russia that might recover lands lost in 1667. [18]Robert Frost, The Northern Wars 1558-1721, page 264

With the warmer weather melting the snow and fresh troops arriving from Sweden, which increased his army to 24,000 men, Charles moved south into Courland. Leaving 6,000 men to watch the Russians he came up against a mixed Saxon and Russian army in July 1701 at the River Dvina near Riga. Here, under cover of a smokescreen made from damp straw and horse manure the Swedish infantry crossed the river in boats, and supported by ships anchored in the river giving covering fire, Charles himself landed with the first wave. The speed of his assault caused consternation in the allied army, which promptly fled the field. The victory however was far from complete as the Swedish cavalry were unable to cross over the river and finish off the panic stricken fugitives. [19]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 346

It was at this stage of the war that Charles made the momentous decision to concentrate all his efforts on the overthrow of Augustus rather than pushing on into Russia to deal with Peter. His reasons for doing so were based upon sound military principles. Having defeated the Russians at Narva Charles felt confident that they posed no great threat, while the Saxons still fielded a strong army in Poland. He also wanted to teach Augustus a lesson for his duplicity in invading Livonia, and considered it, “derogatory to myself and my honour to have the slightest dealings with a man who had acted in such a dishonourable and shameful way.” [20]Ibid, page 346-347 However, the main problem, which Charles failed to grasp, was the difficulty in winning over the Polish nobility, and the Herculean task of appeasing the Polish people and the church with a replacement for the Polish throne.

Undeterred by these problems Charles marched on Warsaw in January 1702, occupying the city on 14th May. On July 8th he defeated a mixed Saxon and Polish army at the battle of Kliszów. In this battle he once again demonstrated his uncanny grasp of timing and tactical judgment. His army was outnumbered by almost two to one and he had only four small three- pounder cannon to the enemy’s forty-six field pieces. Realising that the allied weakness lay on their right flank Charles decided upon a daring enveloping manoeuvre. Reinforcing his own left at a crucial stage of the battle the Swedes withstood two massive Polish cavalry onslaughts before advancing in their turn on the Saxon flank, which had suddenly become exposed as the Polish horse retired. Caught on the bayonets of the Swedish infantry and unable to meet this threat effectively owing to marshland which constricted their left and rear, the Saxons were forced to retire leaving over 2,000 killed and 1,000 prisoners on the field. [21]Robert I. Frost, The Northern Wars 1558-1721, page 272

In the spring of 1703 Charles again defeated the Saxons at the battle of Pultusk (21st April), thereafter proclaiming Augustus dethroned and his own puppet monarch, Stanislaus Leszcznski crowned king. The election of the new king was nothing short of a travesty. On July 2nd 1704 Charles ordered a rump session of the Polish Diet to be gathered together by force of arms in a field outside Warsaw, and under the close guard of Swedish soldiers, they went through the sham ceremony of proclaiming Stanislaus I King of Poland. [22]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 400

While Charles was campaigning in Poland, Peter had not been idle. In January 1702 he had invaded Ingria, defeating the weak Swedish force under General Schlippenbach at Errestfer (7th January). The following year he founded St Petersburg, and in early 1704 his troops were once again before Narva, the siege of which he left in the capable hands of the Scottish mercenary Field Marshal George Ogilvie while he pressed on to Dorpat, which was also under siege by the Russians. The town surrendered on 13th July, and on 30th July Peter was back before the walls of Narva, which fell on 9th August, but resulted in a bloodbath for the defenders because the Swedish commander, General Arvid Horn did not accept Peter’s generous terms of capitulation. [23]Ibid, page 398

Charles paid little attention to events that occurred in the Baltic, considering that the Russians would soon be dealt with and towns and provinces restored to Swedish control after Augustus was cornered and forced to admit defeat. This proved easier said than done as Augustus still commanded a powerful army, and fractional intrigues within the Polish nobility divided his enemies rather than unite them against him. [24]Robert I. Frost, The Northern Wars, page 268

Seemingly undeterred by anything or anyone, Charles suddenly made a forced march into eastern Poland in January 1706 where he hoped to force Ogilvie, who was in winter quarters around Grodno, to give battle. Staying firmly behind their entrenchments the Russians refused to be drawn into a confrontation with the Swedes in the open field, however Augustus, who had moved from Grodno towards Posen attempting to come in on the Swedish rear, was hoping that Ogilvie would move to attack their front. The whole plan never materialised and Augustus was defeated by the Swedish general Rehnskjöld at Fraustadt on 3rd February. Meanwhile Peter had ordered Ogilvie to abandon his artillery and heavy baggage train and fall back across the river Niemen, a move that was carried out with the Swedish army close on his heels. Charles followed the retreating Russians as far as Pinsk where he decided once again to turn south intending to march into Augustus’s homeland of Saxony. Once Charles and his veteran army were firmly established in their own back yard the Saxon ministers in Dresden were forced to conclude a peace with the Swedish monarch, which was signed at Altranstädt on the 26th September 1706, and ratified by Augustus himself on 20th October. By its terms Augustus renounced his alliance with Russia and recognized Stanislaus as King of Poland.

The appearance of Charles and his army at the very heart of Europe caused panic among the Dutch, Austrians and British, all of whom were worried that the Swedish monarch had agreed to an alliance with the king of France. So concerned were they that The Duke of Marlborough himself was sent to Altranstädt to hold an interview with Charles. At this meeting, which took place in April 1707 the Duke concluded that the Swedish presence in Germany posed no threat, and that Charles had no intention of upsetting the balance of Catholic and Protestant powers allied against Louis XIV. At the conclusion of this meeting between two of the greatest commanders in history Marlborough stated his wish to, “…serve in some campaign under so great a campaigner as the Swedish king so that I might learn what I yet want to know in the art of war.” Charles himself was not quite so impressed with the Duke, saying afterwards that he thought Marlborough overdressed for a soldier, and his language a bit overdone. [25]Robert K. Massie, Peter the Great, page 415

The Campaign Against Russia.

With two of his antagonists now out of the fight Charles bent all his efforts in building up his armies for the confrontation with the Russian Tsar that he now so much desired. Military preparations were set in motion and new recruits flooded into the Swedish ranks, whose numbers had now risen to over 30,000. Besides these almost 11,000 fresh troops from Sweden were mustering in Swedish Pomerania and would join the main army when it entered Poland, while a further 12,500 under Lewenhaupt were at Riga, and 14,000 more under Lybecker in Finland awaited orders to strike at St Petersburg; the whole army numbered almost 70,000 men, and although Peter would be able to oppose them with some 110,000, Charles was content that he could deal with any army the Russians could send against him. [26]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 423-424On 27th August 1707 Charles quit his headquarters at Altranstädt and rode into Dresden to pay a last visit to his first cousin Augustus, who now had to be content with the much-diminished title of Elector of Saxony. Thereafter he joined his forward units as they crossed into Protestant Silesia – there would be no turning back.

The bright sunlit roads and pleasant villages of Saxony and Silesia soon gave way to devastated farms and fields as the Swedish army entered Poland. The town of Rawicz had been burned to the ground, and the countryside for miles around turned into a wasteland by bands of Cossack and Kalmuck horsemen. Halting his army at Posen Charles ordered a strong fortified camp to be built. Here he would spend the next two months drilling his troops while he waited for the autumn rains to subside and the first frost to harden the waterlogged roads.

Breaking camp on 26th November the Swedes marched fifty miles from Polsen to the Vistula River, having to spend another month of frustration waiting for ice to form on the river so that a crossing could be made. Then, on Christmas Day 1707 the temperature plummeted and the surface water began to freeze over. Planks and straw were dowsed with water and pushed onto the ice for added strength, enabling the wagons and artillery to pass over with only a minimal loss of life and material. [27]Peter Englund, The Battle that Shook Europe, page 42

Charles, as was his wont, chose the most difficult route eastward, through the Masovian forests, an area so inhospitable that it had never before been used by an army. By doing so he hoped to turn the Russian position on the River Narew. [28]Ibid, page 43 After a ten-day march during which the Swedes killed, tortured and devastated the Masrovian population and its villages, they finally emerged on the plains of Lithuania. By 28th January 1708 Charles, with only an escort of 600 men, crossed over the River Niemen and entered Grodno, the Russian garrison having evacuated the town only hours before. [29]Peter Englund, The Battle that Shook Europe, page 45 Pressing relentless onward the Swedes entered Smorgonie, then turned southeast to Radoszkowicze where, fully realizing that the Russians could keep falling back, and that his own troops were in need of rest, Charles ordered a camp to be built and the country scoured for food and fodder.

Before the commencement of the summer campaign Charles ordered Lewenhaupt’s 12,500 men to march from Courland with a massive supply train and join the main army. The 14,000 Swedish troops under Lybecker had also received orders to advance from Finland and threaten St Petersburg. The Swedish monarch was now faced with two choices, either to continue to follow the Russian army, or to recapture the Baltic provinces lost during his campaigning in Poland. Naturally, given his character, Charles decided that he must finish-off his business with the Russian Tsar first, and thus he choose to plunge on regardless of numbers, time and distance. As Robert Frost tells us, ‘ Charles would have been naïve to believe that Peter would be content with the cession of St Petersburg alone; it was the Russians who would benefit most from a suspension of hostilities. The only way to secure a lasting peace and long-term security for the Baltic provinces was to destroy the Russian army and force Peter to settle on Swedish terms. An invasion of Russia was the only way to achieve that end.’ [30]Robert Frost, The Northern Wars 1558-1721, page 280

Breaking camp on 6th June the Swedish army marched towards Borisov on the River Berezina where some 8,000 Russians under General Goltz were well dug-in and prepared to contest the crossing, and once again Charles completely confounded his opponent by marching south and crossing the river at Berezina-Sapezhinskaya, turning the Russian position and making another defensive river line untenable to the Russians. After this event it was decided that battle must be offered to the Swedes before they managed to cross the River Dnieper, however it was not to be a ‘…risk-everything, life-or-death battle, but a battle that would extract payment from the invaders’. [31]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 442

The Russians took up a position behind the muddy river Babich, across from the town of Golovchin, their lines extending along the riverbank for almost six miles. On the 30th June Charles himself arrived at Golovchin where he was forced to wait for several days until the bulk of his army arrived. After reconnoitring the Russian position Charles noted that the river was fordable and considered that, even with the enemy well entrenched on the far side, their position was so extended as a result of not wishing to allow the Swedes another opportunity of a turning move that it would be possible to break through by direct assault. With his keen eye for topography the Swedish monarch had noticed that the Russian line was divided into two separate portions, separated at the centre by a wooded and boggy area of terrain through which meandered a small stream feeding into the Babich. [32]Ibid, page 442

At dawn on the 4th July all was ready and 7,000 Swedish infantry began wading the river, taking the Russians by complete surprise. Climbing the opposite bank they continued their advance in a slow deliberate fashion. Perplexed and confounded by this surprise attack the Russian commander, General Nikita Repnin [33]Repnin was later court- martialed for his failure at Golovchin ordered up cavalry to attack the Swedish in flank. Fortunately Rehnskjold was at hand with the Swedish Guard cavalry, and these, together with fresh regiments sent across the river forced the Russians to retire. Seeing their cavalry defeated, and now coming under even more pressure as fresh Swedish infantry crossed the river, the Russian infantry on their left flank crumpled and fell back, abandoning their artillery and baggage. At 8 a.m. Charles was ready to turn his attention to the Russian right wing, which had however already begun to retreat towards the River Dnieper.

Despite their defeat and retreat the Russians had fought well, proof that they had gained much in experience and discipline since Narva. Charles however still considered them inferior and held them in contempt, and this was to be the cause of much of his woes. To underestimate one’s enemy, even after defeating him in battle should never be contemplated by even the most brilliant of commands.

On 9th July the Swedish army reached Mogilev on the River Dnieper, the front doorstep of Russia, but to the surprise of the Russian scouts across the river Charles remained firmly on the opposite side. Here until 5th August the 35,000 men of the Swedish army marked time, awaiting the arrival of Count Lewenhaupt’s convoy from Riga. It had been calculated that, given the size of Lewenhaupt’s baggage train, which was to contain enough supplies for the whole Swedish army for six weeks after joining the main body, the 400 miles from Riga to Mogilev would take about two months, starting out in early June. However, Lewenhaupt had problems obtaining sufficient wagons and horses, as well as difficulties in gathering the supplies. Consequently he was not able to begin his journey until late June, while the Count himself only set out to join his troops towards the end of July. Thus, while Charles was kicking his heels at Mogilev expecting to be joined by Lewenhaupt’s welcome supplies and reinforcements, these were in fact still some 250 miles away north of Vilna. [34]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 447

It was while Charles was at Mogilev that he received an embassy from the Hetman of the Ukraine, Ivan Stephanovich Mazeppa. It was suggested that if Charles undertook to take the Ukraine under his protection then Mazeppa would place 30,000 Cossacks at his disposal. Never one to “look a gift horse in the mouth,” Charles saw that this proposal would enable him to use the plentiful resources of the Ukraine to feed his army. For his part Mazeppa, who had originally been allied with Peter in his war against the Turks, became increasingly worried that the Russian Tsar’s reforms would cause the loss of his own independence, and therefore he had decided to throw in his lot with the Swedes. [35]General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World,Vol.II page 169

With his customary impatience Charles broke camp on 5th August, becoming listless at having to await the arrival of Lewenhaupt’s lumbering supply train. Marching close to the Dnieper River the Swedes moved south-east towards the river Soz, hoping to force the Russians into a pitched battle, which proved of no avail, the Russians retiring before their advance leaving nothing but devastation behind them. [36]Peter Englung, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 48

It was now that Charles, possibly for the first time in his life, became uncertain of what course of action to take. At a council of war General Rehnskjöld tactfully advised the king that they should await the arrival of Lewenhaupt’s supply train, which was now of vital importance for the subsistence of the army. After linking up the Swedes would then be able to go into winter quarters in Livonia. [37]General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II, page 170 It was while this council was taking place that an urgent appeal to move south arrived from Mazeppa, who was becoming increasingly afraid that Peter would discover his duplicity and take measures to squash the planned alliance before the Swedes could join him. This made up Charles’s mind for him, and ignoring all other advice he at once decided to join the Cossack Hetman. As General Fuller says,

‘…Not only was Charles a man of impulse who never worked to a plan, but, as Napoleon points out, in this campaign he violated the principles of war: he failed to concentrate his forces; he abandoned his line of operations; cut himself off from his base; and made a flank march in face of his enemy’s army. Outside an offensive idea, Charles had no plan, and in spite of the urgency of Mazeppa’s situation, not to wait for Lewenhaupt was an act of strategic insanity. From now onward Charles’s actions increasingly show that either his faith in himself, or his contempt for his enemy, or both combined, had unbalanced his mind.’ [38]Ibid, page 171. See also, Correspondance de Napoleon, Vol. III, page 207

Lewenhaupt of course knew nothing of Charles’s decision and continued his march to join the main army. Only on 28th September did he receive the news that the king was marching south. His new orders were that he should cross the Dnieper and the Sozh and head for Starodub in the Ukraine. Crossing the Dnieper he reached the village of Lesnaya where, on 9th October he was attacked by a Russian force under the Tsar himself of some 14, 500 infantry and cavalry. The battle was fiercely contested with the Swedes holding their ground all through the day. When darkness descended Lewenhaupt’s position became untenable, as many soldiers attempted to escape. Looting and drunkenness became rife, and it was soon realised that the whole baggage-train and artillery would have to be abandoned. Sharing out the draft horses and salvaging a few light carts the Swedes continued their journey, joining up with their main army on 21st October. Of the original 12,500 men who had set out from Riga in June, only 6,000 tired and ragged men had managed to get through. [39]Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 50

Things had gone no better in the north where General Lybecker had attempted to take St Petersburg. Finding the place well defended he had been forced to pull back to Viborg, losing all his heavy baggage, plus some 3,000 men. [40]General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II, page 171-172

Winter of Discontent.

Charles, now isolated, pinned all his hope on Mazeppa. The Cossack leader had finally declared for the Swedish king but a swift reprisal by the Tsar, in which he had sent General Menshikov to ravage the Zaporozhians homeland had made this alliance a hollow gesture. Mazeppa himself joined Charles at Horki with only a few thousand men, ‘ The insurrection then fizzled out, and the Swedish army was left like a lake in a desert, cut-off from all its feeding rivers.’ [41]Ibid, page 172

Although the Ukraine was plentiful in grain, cattle, fruit and honey, the collecting and distribution of this manna from heaven proved difficult to collect as the coldest winter in living memory began to set in. The severity of the weather was such that the whole of Europe was caught in its icy grip. The Baltic Sea froze, the Rhône River in France froze over; in Venice the canals were coated in ice, while in the Ukraine itself spirit froze solid in the barrels and the birds fell dead from the sky. [42]Ibid, page 172

The Swedes had settled into winter quarters encompassing the towns of Romny, Lokhvitsa, Pryluky and Gadyach, their regiments distributed throughout the area living in huts, barns and houses. Peter however did not intend them to remain long in their cantonments. His new tactics of harrying his enemy and keeping them off balance meant that the Swedes were always being called to arms by Russian feints and diversions. So angry did Charles become with these hit and run tactics that upon learning that the Russian army was approaching the town of Gadyach, and despite the bitter cold he immediately marched to confront them. As Charles moved on Gadyach, so the Russians set fire to the place and moved on Romny. The frost-covered Swedes, hoping for warm billets at Gadyach found that over one-third of the houses had been destroyed leaving scant shelter to accommodate their numbers:

‘If they failed to find some cranny in the ground the men had to stand outside in the extreme cold, under bare skies. People died in droves on the streets. The bodies of hundreds of frozen soldiers, servants, wives and children were collected up each morning, and all day sleds loaded with rigid corpses were driven off to be hidden in some hillside cavity. The field-surgeons worked round the clock. Barrels filled with amputated limbs taken from victims of frost-bite.’ [43]Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 51

Undeterred by the suffering around him Charles hit back at the Russians in early January 1709 striking at the town of Veprik, and then at the end of February, with only a few hundred men, he trounced several thousand Russians at Krosnokutsk, and again at Oposzanaya. [44]General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II, page 173

A sudden rise in temperature now put a stop to all operations, heavy rain turning the ground into a quagmire. The Swedes went into camp between the Psel and Vorskla rivers. Of the 40,000 troops at his disposal after the arrival of Lewenhaupt’s tattered band in October 1708, Charles’s command was now reduced to a mere 24,000, among whom were some 2,250 sick and wounded. [45]Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 56

Grasping at Straws.

The long drawn out Ukrainian winter slowly gave way to spring, and by April 1709 as the ground warmed, grass and flowers began to push their way up from the earth. It was at this time, and while Charles was in negotiations with the Turkish Sultan and Crimean Tartars with a view to forming an alliance, that he decided to move further south so that he could be closer to the expected reinforcements arriving from Poland. To this end he set his army in motion intending to lay siege to the small town of Poltava on the Vorskla River, some 200 miles southeast of Kiev on the Kharkov road. [46]Robert Massie, Peter the Great, page 479 Just why the Swedish king, whose reputation had been forged on the open battlefield, and who always sought a decision by swift and vigorous action now choose to tie himself down with methodical and ponderous siege operations is something of a mystery. One possibility was that although the town was well positioned on a high ridge overlooking the Vorskla its wooded ramparts were not up to the standards of European fortifications, and if Charles had moved on the town in the previous autumn he could have taken it with little effort or cost. Now however the Russians had had time to strengthen the defences and garrison the place with over 4,000 men supported by ninety cannon, also Menshikov was now approaching the eastern bank of the Vorskla, opposite Poltava, with the Russian field army. Small wonder then that Charles’s Generals were at a loss to understand why their swashbuckling monarch had chosen the spade instead of the bayonet, particularly with most of their powder ruined by the damp, and their supplies of musket and cannonballs dangerously low. [47]Ibid, page 480

Parallels and approaches were dug, and on 1st May the bombardment began. After six weeks of digging and mining the Swedes had little to show for their efforts, this despite the Russian garrison itself running short of cannonballs and being reduced, in some cases to firing stones and rotting vegetation into their trenches. Charles himself was even struck by a dead cat, so desperate had both sides become due to the shortage of ammunition. [48]Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 55

Early in June Peter joined Menshikov at the Russian camp, their combined forces now numbering over 40,000 men, and now decided to harass the Swedish foraging parties. He also planned to launch a feint attack across the river to the south of Poltava, under cover of which the main army would pass over to the western bank north of the town. [49]General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II, page 175

Swedish cavalry

Meanwhile the Swedish position had become so critical that Charles asked Lewenhaupt for his opinion of the situation, to which the general advised an immediate retreat across the Dnieper River so that contact could once more be restored with Poland. This plan was not at all to the Swedish king’s liking, he not being one to turn tail and run even when circumstances dictated. Dismissing Lewenhaupts sage advice, on the morning of 17th June, his twenty-seventh birthday, Charles was disturbed by the sound of Peters faint attack across the river, and rode out with the general to see for himself what was taking place. Riding to within musket range of the Russians he was struck by a ball, which hit him in the left foot, travelling along the whole length from heel to toe. Refusing to dismount he soon began to swoon in the saddle from loss of blood, and finally had to be lifted from his horse. The wound was not merely confined to the king himself; its effects would seriously impair the Swedish army who had become so reliant upon their monarch’s presence and control on the battlefield.

Peter’s faint attack had done the trick, while the Swedish king was hastening to the south the Russian main army had crossed the Vorskla some six miles to the north of Poltava where a strong fortified camp was constructed near the village of Semenovska. When Peter heard the news of Charles being wounded he immediately decided that the time was now ripe to offer battle, but only a defensive one, he still erred on the side of caution, and was at pains to make sure that all the necessary measures were taken to ensure his army would not be caught in the same predicament that they had found themselves in at Narva.

For three days Charles lay overcome by fever, finally on 22nd June it broke, much to the relief of his generals, however the military situation had worsened. First news from Poland had arrived informing him that Stanislaus was unable to come to his aid. The insecurity of the Polish throne and the instability of the country in general had put a scare up Charles’s puppet king, and no help could be expected; to compound the problem another message arrived stating that the Turkish Sultan had refused Devlet Gerey, the Khan of the Crimean Tartars to assist the Swedes. Charles’s dream of marching on Moscow was rapidly turning into a nightmare.

The Russians were now firmly established on the west bank of the river, and Peter became even more determined to draw the Swedes into giving battle. On the night of 26th June the army moved from its camp at Semenovka marching south towards the village of Yakovetski, barely four miles from the walls of Poltarva itself. Just outside the village another massive fortified camp was constructed, as well as a strong line of six redoubts blocking access to the plain. The construction of the camp was in the form of a quadrilateral, with a deep ditch and drawbridge access gates to facilitate troop exit and security, however, ‘…The rear of the new camp overlooking the bluff of the Vorskla at a point where the bank was so steep and the river so broad and marshy that it would be impossible for large numbers of men to cross in either direction. Thus, the only retreat for an army in this position would be north, back to the ford at Petrovka.’ [50]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 489

On the 27th June, now realising that his position was becoming untenable, Charles held a council of war, at which he informed his generals that he intended to seek a decision by forcing a battle the following day. He had noted that the Russians appeared to have built themselves a death trap. With the river to their rear, and their only escape route back to the north, Charles considered the situation to be most favourable for a sudden lightening attack. To this end, and fully realising that his wound would not permit him to perform his normal battlefield duties, he appointed Field –Marshal Rehnskjöld to command the army. The plan consisted of two rapid manoeuvres: a break out into the plain past the Russian redoubts, and a full scale assault on the fortified camp. The first part of the plan would take place just before dawn, with the army moving rapidly past the redoubts before their defenders were fully awake. Infantry and cavalry would work in unison. The cavalry would take out the enemy cavalry guarding the rear of the redoubts, and then move to cut off the main line of retreat to the Russian army from the north. The infantry would follow in the wake of the cavalry, bypassing the redoubts and then assailing the fortified camp. [51]Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook The World, page 68 Lewenhaupt proposed that the siege of Poltava should be raised, allowing for the maximum number of troops to take part in the battle, but Charles was persistent, considering that the defenders should remain bottled-up within the walls. To do so, 1,300 men were held back to watch the fortress, another 2,000 were placed to guard the baggage train, and a further 1,200 left to watch the western bank of the Vorskla in case of any movement that threatened the main body of the Swedish army on their flank. Thus, Rehnskjöld’s command had been whittled down to a meagre 16,000 men, half cavalry and half infantry. Because of the poor quality of the Swedish powder, and the shortage of musket balls, the attack was to be carried out predominantly with cold steel. With the exception of four light cannon all other ordnance was to be left with the baggage train, speed being considered essential for victory. [52]Ibid, page 86

The Battlefield.

The town of Poltava sat atop of a plateau, close by the Kiev-Karkov Road, on the western bank of the Vorskla River; the river itself meandered its way from north to south where it flowed into the Dnieper. The ground around the little fortress was cut up by steep ravines, and here and there dotted with fields and woodland. To the north, separating the Swedish fieldworks from the Russian camp stood the Yakovetski woods, through which another deep gully slashed the ground from north to south. About three miles northwest of the town yet another boggy depression bisected the plain, beyond which the ground became gradually higher and covered in orchards and vineyards around the villages of Tachtaulova and Pobivanka. The Swedish baggage train, together with several thousand Cossacks, whom Charles considered of little use in the coming battle, was to the south west of Poltava, near the village of Pushkaryavka.

The Battle.

The Swedish infantry moved forward to their assembly points just after 11 p.m. on that fateful Sunday night of 27th June, the point of no return had been reached, and despite their tattered uniforms and meagre diet the men were full of confidence; the password to be used in case of confusion due to the smoke of battle was “With Gods Help.” Charles was carried forward on a litter, his wounded foot had been freshly cleaned and bandaged and his sword was laid at his side. [53]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 493Arriving at their assembly point the infantry were ordered to sit down while they waited for the cavalry to come up.

Unfortunately the cavalry were late getting started. Because Rehnskjöld had been given command of the entire army, his normal roll as head of the Swedish horse was sadly missed, and some confusion with getting the cavalry mounted and moving off in their six columns caused a time consuming delay in their arrival. Also, and this was to be even more of a contributing factor to their defeat, Rehnskjöld had not informed Lewenhaupt of his plans. Indeed, he disliked the general so much that it took the Field Marshal all his time to utter a single word to Lewenhaupt even when they were called together at a war council. Because of this other generals within the army were as equally in the dark concerning the battle plans as Lewenhaupt, small wonder then that command and control began to fall apart soon after the battle began. This itself is a damning indictment on Charles’s attitude on this crucial occasion. By not issuing written instructions to all of his field commanders with clear and exact orders as to what was expected, he, and he alone must bear the blame for the confusion and defeat that followed. [54]Ibid, page 491

Sometime towards 1.00 a.m. the sound of hacking and digging filtered through from the Russian lines, far nearer than the Swedes had reckoned them to be. Rehnskjöld rode forward quietly with a few officers to find out what was happening. To his surprise he was able to discern through the early morning darkness that the Russians were in the process of building a new line of four redoubts, extending forward at right angles from the original six that blocked the assess to the plain. These new obstacles now meant that the Swedish attacking columns would be split into two groups, passing to each side of the redoubts they would come under a flanking fire from cannon and musket well before they could come to grips with the Russian main army. While Rehnskjöld was taking all this in, he noticed that the last two redoubts, those to which he was closest, were not complete. As his eyes grew more accustomed to the darkness the Russians working on the redoubts spotted him. Shots were fired and drums began to beat, to which the Swedish Field Marshal made a hasty retreat. [55]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 494

Realizing that the element of surprise had now been lost Charles conferred with Rehnskjöld about whether the attack should be called off. There was now no hope of a quick breakthrough, the new system of redoubts meant that the Swedes would have to fight to gain access to the plain. With only four small artillery pieces they had no chance or time to reduce each redoubt in turn, and no means of fabricating assault ladders or collecting brushwood to fill the ditches and scale the walls. [56]Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 91 The Field Marshal informed his monarch that in his opinion the attack should commence at once, the cavalry had now arrived and the longer they delayed the more time the Russians would have to bring up more troops to block the Swedish advance. Charles agreed and new scratched together orders were issued. The infantry was now formed into five columns, four of which were instructed to pass the enemy works as quickly as possible, while the fifth column stormed the new line of redoubts, hopefully masking their fire while the main body of the Swedish army moved through.

At 4.00 a.m. on 28th June, as the sun began to creep above the horizon flooding the landscape with light, the Swedish infantry moved forward. To their rear the cavalry conformed to the general tide of advance. For the most part the plan went well, most of the army flowing past the redoubts. However, things began to go wrong for the central column of infantry, which, although meeting with success by capturing the first two Russian works, thereafter, instead of joining the main army, became embroiled in trying to storm the third redoubt. This fieldwork was stoutly defended, and the Swedish general in command of this column, Karl Gustav Roos, being repulsed after his first attempt to take the redoubt, now committed his entire six battalions, some 2,600 men into gaining the place come what may. [57]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 495

While Roos squandered his precious battalions Charles, with the left wing of the Swedish army pushed on towards the rear line of redoubts. Here they were met by a strong force of Russian dragoons under Menshikov who flooded out from between the earthworks. A cry arose from the Swedish ranks, “Advance cavalry,” and their massed squadrons of blue-coated troopers lurched forward into the oncoming Russian tide. Amidst the swirling smoke and dust both sides laid-on with cold steel, neither side gaining the upper hand. So it went on for over an hour. By this time Menshikov was fully convinced that he had the measure of his enemy, and sent an urgent message back to Peter at the main Russian camp to come forward with the whole army. Peter however was still uncertain about the situation, fearing that Menshikov may have only gained a localised success, and that the resilient Swedes were holding something back. The order for the Russian cavalry to fall back was issued which, reluctantly, Menshikov conformed to, pulling his squadrons back to the north to cover the approaches to the Russian camp. [58]Ibid, page 496

On the Swedish right Lewenphaut, commanding six battalions of infantry, and again with no clear idea about the overall plan of battle, was passing the redoubts to the east. Advancing through the chocking dust kicked up by the cavalry engagement as well as a galling fire from the Russian works Lewenhaupt altered his line of march even further to the right, away from the main body of the army. His one thought, as a true fighting general, was that he should get to grips with the enemy as soon as possible. Not only this but the ground was better the further he moved to the right, and the fact that he was fast approaching the main Russian camp made him even more determined to show what Swedish infantry were capable of. Like David facing Goliath the little band of Swedes, only 2,400 strong were quite prepared to storm the Russian camp where over 25,000 men and almost eighty cannon awaited them. Just as Lewenhaupt was realigning his battalions for the assault he received an order, ‘…so he says- from “a loyal servant of the King” to halt. Though amazed and indignant, for he believed that he had victory within his grasp, he had no option but to obey it. Who sent the order has never been made clear; Rehnskjöld vigorously denied that he had done so, and so did Charles. The truth would seem to be that throughout the battle Charles and Rehnskjöld gave orders alternatively, and that after the initial success of the Swedish left wing, confusion reigned and orders and counter-orders chased each other over the battlefield.’ [59]General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, page 181

After the withdrawal of the Russian cavalry the Swedish left wing, together with Charles and Rehnskjöld had passed the redoubts and drew up in the open plain beyond, it was 6.00 a.m. The Field Marshal was well satisfied with the progress thus far made. It was only when he realised that a third of his infantry force was missing that Rehnskjöld sent an urgent message back to Roos ordering him to break off the attacks on the redoubts and join the main body. Time passed with still no sign of the missing battalions. Worse was to follow. Even if the Swedish high command did not know the whereabouts of Roos’s snagged up infantry, Peter certainly did. Seeing the isolation of Roos’s corps he immediately sent forward several thousand cavalry and infantry under general Rensel to cut them off from the main body. Under the stress and heat of battle Roos’s men mistook the advancing Russians for their own troops. Soon they were surrounded, and after a gallant struggle in which most of his command were either killed or captured, Roos finally managed to break out towards Poltava with only 400 men. Here they took cover inside an abandoned trench where they were finally forced to surrender. [60]For a detailed account of this action see Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 116-124

At 9.00 a.m. Lewenhaupt’s six battalions finally made their way to join the main army. For The Swedes the situation was rapidly deteriorating. Even though they had managed to pass the redoubts and drive away the Russian cavalry the chance of victory was ebbing away and it was time for Rehnskjöld to make a decision. Should he move north and attack towards the ford at Petrovka, cutting the Russians off from their supply line? This plan was dubious given the reduced strength of the Swedish army; should he push on and attack the main Russian camp itself while most of their troops were bottled up inside? This too was doubtful given the fact that the camps approaches were well covered by artillery to which the Swedes had nothing to reply with. Finally, should he order a retreat, save what he could from the shambles, and gather the remaining troops around Poltava and consolidate? This latter plan seemed the better part of valour. By gathering together his forces he would then be able to fight another day. [61]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 501

Unfortunately for Rehnskjöld his mind was made up for him before he had a chance to put his own plans into operation. Just as he had given orders for the men to form up in column of march ready to move back in the direction from which they had come, his attention was suddenly drawn to the Russian camp where much signs of activity was taking place. As the Swedes watched, the drawbridges of the fortification were being lowered across the surrounding ditch, and across them began to pour thousands of green clad Russian soldiers- Peter intended to fight.

The operation was carried out smoothly. The Russian infantry formed in the centre, while their cavalry deployed on the wings. Leaving sufficient cannon on the ramparts to fire over the heads of their troops, other guns were brought forward into the front line. Peter himself rode with the Novgorod regiment on the Russian left, resplendent in the green uniform the Preobrazhensky Guard. [62]Ibid, page 502

Realising that his formations could be seriously compromised if the Russians attacked while his troops were still in column of march, Rehnskjöld once again ordered his men back into battle formation, then rode over to consult with the king. “Would it not be best if we attacked the cavalry first and drove that off?” inquired Charles. “No Your majesty.” Rehnskjöld replied, “We must go against their infantry.” Being unable to view the situation owing to his position lying on his back, Charles concurred saying, “Well you must do as you think best.” One can hardly believe that these words were being spoken at such a crucial moment by one of the most aggressive and assertive commanders in history. [63]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 502

As the Swedes shook themselves back into line Peter was delivering a short speech to his troops. Since it would have been impossible for him to be heard by any but those close to him, we may conclude that his words were only made to his own retinue. Thereafter the Russian juggernaut, 30,000 strong began to move forward in two lines over a mile wide. Because of the depleted state of the Swedish army their battle frontage was considerably shorter than the Russians. With only twelve under strength battalions available, and these spread out thinly in one line, the Swedes could only show a frontage of around fifteen hundred yards, which meant that each of their flanks was overlapped. Their cavalry was still to the rear, trying to sort themselves out after their struggle with Menshikov’s dragoons, but General Creutz, commanding the Swedish horse was desperately trying to reform his squadrons and attempt to come to the assistance of the infantry. [64]Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 141

At 10.00 a.m. Rehnskjöld rode over to Lewenhaupt and, putting aside his animosity towards the general took him by the hand saying, “Count Lewenhaupt, you must go and attack the enemy. Bear yourself with honour in his Majesty’s service.” Quite taken aback by this sudden turn of attitude by the Field Marshal, Lewenhaupt asked if he was being given a direct order to attack. “Yes, at once,” Rehnskjöld replied. “In God’s name, then, and may His grace be with us,” said Lewenhaupt. [65]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 502 The Swedish “Charge of the Light Brigade” was about to commence.

Despite all the odds the 4,000 Swedish infantry moved forward, drums beating. Above the ranks in their tattered and threadbare blue uniforms flew their battle standards, as worn and scarred as the men who marched beneath them, but slapping proudly in the warm summer breeze. Soon solid shot from the Russian cannon was ploughing bloody lanes through the ranks, taking off arms, legs and heads, but on they came. At 100 yards the Russian artillerymen changed to grape and scrap shot spewing a hail of iron into the oncoming Swedes. Dozens fell with each blast; their bodies riddled and shredded, and still they marched on. With backs and heads bent forward as if bracing themselves against a blizzard the Swedish battalions now came under volley fire from the Russian infantry, the sound of the impact upon their bodies not unlike that made when throwing handfuls of stones into a mud pile. Still they pressed on without firing a shot in return, and although the line was now far from aligned correctly, the Guard battalions on the Swedish right burst into the Russian ranks, driving them back on their second reserve line.

Desperately Lewenhaupt cast around to see if the cavalry were now coming to exploit the breakthrough, but no Swedish squadrons were to be seen. The general noticed that the left wing of his line was in difficulty as the Russians had moved numerous cannon to this part of the field to cover their cavalry to the north. Here the concentrated fire from the guns cut down the Swedish battalions before they could get to grips with their foe. With the right wing still pressing forward, and the left wing clearly faltering, a dangerous gap was now being created in the Swedish battle line. [66]Ibid, page 504

Like Lewenhaupt, Peter had also noticed that the Swedish line was now becoming unravelled, and also that their cavalry was conspicuous by its absence. Sensing that the time had come to deliver a counter stroke Peter ordered his infantry into the increasing gap between the Swedish wings. The discipline of the Russians had improved dramatically over the years. Constant drilling and an improved officer class, coupled with Peters iron will to raise his armies morale and fighting capabilities had transformed it since Narva, and although having been forced to give ground on some parts of the line, it had not been routed.

The same could not be said for the Swedes, who began to show signs of panic within their ranks. Most of their officers had been killed or wounded and with no apparent support forthcoming many soldiers on the left wing began to throw down their muskets and try to escape from the carnage; as Peter Englund so well puts it, ‘ An army is no more than a rigidly organized crowd of men. Under stress it obeys the same laws as any other crowd. The mass of fleeing men all pull each other along in the same direction. Each finds security in the herd, none thinking that he personally will fall victim in the mindless stampede. To get them to stand and turn and face the very threat which was lending their feet wings was no easy task.’ [67]Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 161

The Swedish cavalry now began to arrive, but not in strength. Creutz had managed to bring up about ten squadrons on the right wing, but the rest of the horse were still bottled-up behind their infantry over on the left. The Russians had spotted the advance of the Swedish troopers and, thanks to years of training and drill, the four battalions of the Nizhni-Novgorod regiment, together with the Busch Grenadiers quickly threw themselves into a large hollow square formation with cannon at each corner. This human redoubt spewed forth such a hurricane of fire that Creutz’s squadrons could do no more than mill around it vainly trying to seek an opening. As they were endeavouring to reform, Menshikov’s massed squadrons who had come around them in a wide arc hit them from behind. To their credit and outstanding morale and discipline, the Swedes managed to turn and face this new threat. Not only this but they charged the Russians in their turn, causing them to retire. [68]Ibid, page 158-160

Such gallantry deserved a better fate but it was now far too late to redeem the situation on the Swedish left. Here panic and disorder reigned and soon spread to the rest of the battalions, and although Lewenhaupt did his best to stem the route his words and actions were of no avail. Even the arrival of their cavalry could not stop the stampede of infantry seeking safety back to the south.

Charles was also caught up in the disaster. As the Swedish line collapsed he tried to rally his fleeing men with the vain cry of “Swedes! Swedes!” but his words fell on deaf ears. Indeed, so great was the Russian fire that of the King’s twenty-four litter-bearers, twenty- one were either killed or wounded, while the litter itself was shattered by a cannon ball. Charles was in a perilous situation, and only the swift action of his few remaining officers saved him from death or capture. Placing the king on a horse, his wounded foot bleeding profusely, he was finally led from the field. On the way he met Lewenhaupt and asked the general his opinion of the situation. “There is nothing to do but try and collect the remains of our people” Lewenhaupt replied. Some of those “remains” were in remarkably good condition, particularly some of the cavalry formations from the left wing. Soon a substantial group closed around the king enabling him to retire safely back to the Swedish camp at Pushkaryovka. [69]Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 505

Of the 19,000 or so Swedes who had taken part in the battle almost 10,000 had been left on the field, 6,900 of whom were either dead or wounded, while another 2,800 were taken prisoner, Field Marshal Renskjöld amongst them. The Russians lost far less. Out of a combined total of over 40,000, they suffered 1,350 killed, and 3,300 wounded. The discrepancy can be seen in part as Swedish aggression versus Russian defensive tactics. However the solid stance of the Russian infantry, when compared to their record in all previous engagements with the Swedes shows that they had matured into a resilient and powerful fighting force.

After the battle Charles pulled together what remained of his army and retreated down the Vorskla River to its confluence with the Dnieper. Here, on 29th June, finding it impossible to gather sufficient boats to transport all of his forces across before the victorious Russians caught up with them, Charles quit his army and was ferried over the Dnieper with a body-guard of 1,000 soldiers. On 30th June Lewenhaupt surrendered to the Russians with 12,000 tired and disheartened men – the Swedish army had ceased to exist.

As General Fuller remarks:

‘The battle of Poltava was more than the usual tussle between two neighbouring peoples, for it was a trial of strength between two civilizations, that of Europe and that of Asia, and because this was so, though little noticed at the time, the Russian victory on the Vorskla was destined to be one of the most portentous events in the modern history of the western world. By wresting the hegemony of the north from Sweden; by putting an end to Ukrainian independence, and by ruining the cause of Stanislaus in Poland, Russia, an essentially Asiatic power, gained a foothold on the counterscarp of eastern Europe. [70]General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II, page 184

Graham J.Morris

February 2006

Bibliography.

| Creasy, Sir Edward, | The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World. London, 1893. |

| Englund, Peter, | The Battle That Shook Europe. Paperback edition, I.B.Tauris & Co, London, 2003. |

| Frost, Robert I, | The Northern Wars 1558-1721. Paperback edition, Longmans/Pearsons Education, England, 2000. |

| Fuller, General J.F.C., | The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II, London, 1963. |

| Massie, Robert K., | Peter the Great, Paperback edition, Sphere Books (Abacus), London, 1987 |

.

References

| ↑1 | Quoted in Sir Edward Creasy’s, The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World, page 270 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 29 |

| ↑3 | Ibid, page 30 |

| ↑4 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 295 |

| ↑5 | General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II page 162 |

| ↑6 | Robert I. Frost, The Northern Wars 1558-1721, page 228 |

| ↑7 | Ibid, page 228 |

| ↑8 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 312 |

| ↑9 | Ibid, page 312-313 |

| ↑10 | Ibid, page 314 |

| ↑11 | General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol II, page 164-165 . The treaty had been drawn up in 1697. By its terms Sweden promised to back the Maritime Powers against Louise XIV. The Altona agreement of 1689 pledged help for Sweden by the Dutch and English. |

| ↑12 | Robert I. Frost, The Northern Wars 1558-1721, page 229 |

| ↑13, ↑16 | General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol II, page 165 |

| ↑14 | Robert Massie, Peter the Great, page 327 |

| ↑15 | Ibid, page 328 |

| ↑17 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 329 |

| ↑18 | Robert Frost, The Northern Wars 1558-1721, page 264 |

| ↑19 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 346 |

| ↑20 | Ibid, page 346-347 |

| ↑21 | Robert I. Frost, The Northern Wars 1558-1721, page 272 |

| ↑22 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 400 |

| ↑23 | Ibid, page 398 |

| ↑24 | Robert I. Frost, The Northern Wars, page 268 |

| ↑25 | Robert K. Massie, Peter the Great, page 415 |

| ↑26 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 423-424 |

| ↑27 | Peter Englund, The Battle that Shook Europe, page 42 |

| ↑28 | Ibid, page 43 |

| ↑29 | Peter Englund, The Battle that Shook Europe, page 45 |

| ↑30 | Robert Frost, The Northern Wars 1558-1721, page 280 |

| ↑31 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 442 |

| ↑32 | Ibid, page 442 |

| ↑33 | Repnin was later court- martialed for his failure at Golovchin |

| ↑34 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 447 |

| ↑35 | General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World,Vol.II page 169 |

| ↑36 | Peter Englung, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 48 |

| ↑37 | General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II, page 170 |

| ↑38 | Ibid, page 171. See also, Correspondance de Napoleon, Vol. III, page 207 |

| ↑39 | Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 50 |

| ↑40 | General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II, page 171-172 |

| ↑41, ↑42 | Ibid, page 172 |

| ↑43 | Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 51 |

| ↑44 | General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II, page 173 |

| ↑45 | Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 56 |

| ↑46 | Robert Massie, Peter the Great, page 479 |

| ↑47 | Ibid, page 480 |

| ↑48 | Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 55 |

| ↑49 | General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II, page 175 |

| ↑50 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 489 |

| ↑51 | Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook The World, page 68 |

| ↑52 | Ibid, page 86 |

| ↑53 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 493 |

| ↑54 | Ibid, page 491 |

| ↑55 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 494 |

| ↑56 | Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 91 |

| ↑57 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 495 |

| ↑58 | Ibid, page 496 |

| ↑59 | General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, page 181 |

| ↑60 | For a detailed account of this action see Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 116-124 |

| ↑61 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 501 |

| ↑62 | Ibid, page 502 |

| ↑63, ↑65 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 502 |

| ↑64 | Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 141 |

| ↑66 | Ibid, page 504 |

| ↑67 | Peter Englund, The Battle That Shook Europe, page 161 |

| ↑68 | Ibid, page 158-160 |

| ↑69 | Robert K.Massie, Peter the Great, page 505 |

| ↑70 | General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II, page 184 |