1899-1902

“ Such was the day for our regiment

Dread the revenge we will take.

Dearly we paid for the blunder-

A drawing-room General’s mistake

Why weren’t we told of the trenches?

Why weren’t we told of the wire?

Why were we marched up in column

May Tommy Atkins enquire….” [1]From the ‘Battle of Magersfontein’, verse by Private Smith of the Black Watch December 1899. Quoted in, ‘Thomas Pakenham’s, ‘The Boer War’, page 115.

Introduction.

When the Staff College was established at Camberley in 1858, one of its main purposes was to remedy the appalling deficiencies that had been revealed during the Crimean War (1853-1856), ‘Tested by a major engagement the Wellingtonian army had been found wanting.’ [2]‘The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army’. Page 184 Although the British army became stimulated by a profound interest in its previous campaign, it also went off at a tangent and, after the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 turned its attention to the strategy and tactics of the Prussian General Staff Commander, Field Marshal Helmuth Graf von Moltke (1800-1891) to the exclusion of all others. In particular it almost totally ignored some of the fundamental changes brought about by events in the American Civil War (1861-1865). The annual outpourings from the publishing house of Gale and Polden of Aldershot, after 1870, gave particular attention to such battles as Mars-la-Tour, Gravelotte and Sedan, [3]McElwee.William, ‘The Art of War’, page 214. McElwee also says that the firm of Gale and Polden had well over one hundred thousand books on military history in stock at the turn of the century … Continue reading and even though Sir Garnet Joseph (later Viscount) Wolseley, in his work, ‘The Soldier’s Pocket Book’ (1869) stressed the importance of preparing for war in time of peace, [4]‘The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army’, page 194 it really only considered home defence, the army still being happy with its role in campaigning against natives and tribesmen.

British commanders had indeed learnt the lessons of the Crimean War, and could adapt themselves to battalion and regimental columns manoeuvring in jungles, deserts and mountainous regions; what they failed to comprehend was that when they came up against the Boers all their tactical and technical skills were of little use because they had entirely failed to comprehend the trench fighting and cavalry raids of the American Civil War. In 1899 all arms of the British service went to war with what was to prove antiquated tactics, and in some cases antiquated weapons. [5]Carver, Field Marshal Lord, ‘The Boer War’, Page 259-262

What the Boers presented was a new approach to warfare. The average Burghers who made up their Commandos were farmers who had spent almost all their working life in the saddle, and because they had to depend on both their horse and their rifle they became expert light cavalry and skilled stalkers and marksmen. They could make use of every scrap of cover, from which they could pour in a destructive fire using their modern Mausers. They also had around one hundred of the latest Krupp field guns, all horse drawn and dispersed among the various Commando groups, and their skill in adapting themselves to first-rate artillerymen shows them to have been a versatile adversary. [6]Pakenham. Thomas, ‘The Boer War’, page 30

They also had no problems with mobilisation, since the Presidents of the Transvaal and Orange Free State simply signed decrees to concentrate within a week and the Commandos could muster between 30-40,000 men. [7]Ibid, page 56 They do not appear to have kept any regular muster roles and they habitually falsified their casualty returns; however at the height of the war they probably had around 50,000 men in the field, many of which were Dutch rebels from Natal and Cape Colony who were considered to be poor fighting stuff compared with the solid Boer from the Republics. [8]McElwee.William. ‘The Art of War’, page 215 The main thing is, that it was the latter who fought the British army in the opening stages of the campaign, and who gave Britannia a very bloody nose.

The British Tradition.

The British army of 1899 was ill equipped both mentally and materially to deal with such antagonist as the Boers. True, the officers and men had seen far more active service than most of their Continental counterparts, but it was all largely irrelevant to the conditions of a major campaign against a skilled and determined enemy armed with modern weapons. Not only this but the “small wars” which the British army were almost constantly involved in throughout the late nineteenth century tended to make both officers and men not only complacent, but also rather arrogant in the face of what they considered to be a handful of rustic Dutch farmers who could soon be brought to heel by well disciplined regulars. [9]A very interesting light is thrown upon this topic by Colonel C.E.Callwell in his work, ‘Small Wars”, page 51.Here, although accepting that the Boers were very good fighters, the author still … Continue reading

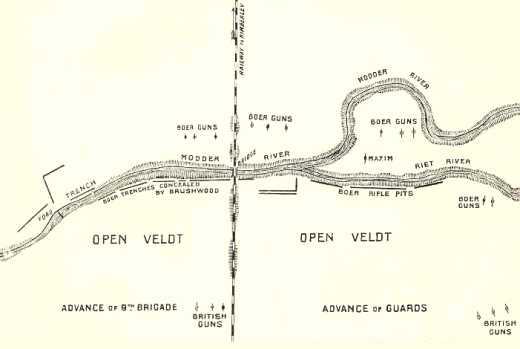

The British infantry had already had a taste of what to expect during the First Boer War of 1880-1881, in which they had once again demonstrated that their bravery was matched by their stupidity in not adapting to modern tactics. At Majuba Hill on 26th February 1881 the Gordon Highlanders had been overwhelmed by Boer rifle fire, which should have made glaringly obvious that things were not as they were set down in the British infantry manuals. That nothing had been done to remedy these defects in 1899 is shown by the way that General White’s force was caught at Nicholsons Nek (29th October 1899), where the British infantry followed exactly the same tactical pattern that had cost them so dear at Majuba. [10]McElwee. William, ‘The Art of War’, page 233. Even after this disaster some British commanders still tried to dismiss their own shortcomings, and attempted to place all the onus on the way in which the enemy fought, ‘This has not been a successful day. As a matter of fact we were so greatly outnumbered that it would have been impossible for us to hope for success in the open field against a mounted and mobile force. But we have anyway made them show their numbers and guns.’ [11]Carver, Field Marshal Lord. ‘The Boer War’ page 20 Statements like this go to prove how little had been learnt from such exponents of mounted warfare as General Nathan Bedford Forrest, and General Joe Wheeler, both of whom used very similar tactics to those employed by the Boers back in the American Civil War. Likewise the wrong assumption that the Boer could not advance in the open, on foot because he had no training to do so, was to totally misunderstand the fact that they had no need to, for the simple reason that they preferred to entrench and let the enemy use its own aggressive training to try and dislodge them, with all of the consequences that this entailed trying to ‘go-in with the bayonet.’ [12]Colonel C.E.Callwell, ‘Small Wars’, page 399 The well constructed Boer trenches at the Modder River (28th November 1899), over four miles long, and dug and concealed on the “forward” bank of the river, together with others rising in tiers towards the crest of the hills beyond, portended things to come in 1914-1918. [13]Jackson, Tabitha. ‘The Boer War’, page 58-59 The British commander, Lord Methuen, was convinced that the Boers would not make a stand at the Modder, and chose to ignore some large white stones that had been placed as range markers for the Boer artillery, as well as playing down reports that there were large numbers of enemy to his front, turning to one of his officers he remarked, ‘I tell you they are not here’, to which the latter replied, ‘They are sitting uncommonly tight if they are sir.’ [14]Ibid, page 59

To be fair to Methuen the blame should not all be heaped on his shoulders, and a great deal of finger pointing should be levelled at the British Army Intelligence Service, which, together with very poor reconnaissance by the cavalry, furnished commanders with out-of-date maps and insufficient probing and information gathering. [15]McElwee. William. ‘The Art of War’, page 234 Thus the same thing was to happen over and over again with disastrous results during the first months of the war. The British infantry became pinned down without much cover, under the boiling sun, without an enemy in sight or the means of retreat, and Methuen’s “Pyrrhic” victory was only due to the fact that the Boers were content to retire to even stronger positions further back, than to any tactical supremacy shown by the British commander. [16]Ibid, page 235

If the British infantry had to learn the lessons of modern warfare the hard way, the British cavalry were also in for a shock when it came to putting the spit and polish of her classic cavalry methods into practice on the plains of South Africa. The cavalry officer class, perhaps above all others within the British army, were particularly slow at learning from the lessons of their own campaigns, to say nothing of not studying anything of the mounted tactics of the American Civil war. Even with the more enlightened writings of George Henderson and Colonel George Denison, both of whom understood the changes that had occurred in cavalry organisation and tactics as a result of the American experience, the majority of the cavalry officer class considered that they could learn nothing from a war in which there had been no cavalry charges at Gettysburg because the mounted forces available were not disciplined enough to engage in one, and that nothing much could be done with volunteer horsemen who preferred the pistol and carbine to the sabre. [17]See both McElwee, page 223, and the very interesting account of how General Phil Sheridan was received in Europe in 1870 by various Prussian and English Generals. ‘Personal Memoirs of P.H.Sheridan … Continue reading The fact that the regular British cavalry regiments had the carbine thrust upon them did not go down well owing to the extra weight, and they were reluctant to relinquish the lance which if anything was even more of an inconvenience, and this outdated weapon was still in service up until 1917 awaiting the chance to be used in the pursuit of a beaten foe! [18]‘The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army’, page 219

In 1888 there had been steps taken by the War Department in ordering many of the County battalions to form detachments of mounted infantry because it was easier and quicker to train infantrymen to a basic standard of horsemanship than to try and retrain a regular cavalryman, who not only resented the task in the first place, but also had the full support of his colonel in not wasting his talent on such unnecessary gimmicks. [19]McElwee. William. ‘The Art of War,’ page, 224 It was only after yet another blunder at Bloemfontain where General Broadwood was ambushed in April 1900, that the skills of the British mounted infantry, together with the aid of their better-trained New Zealand allies, began to dawn on a few cavalry commanders, but even this did not stop some, like General French, from criticising the fact that these units were crippling the army, especially the regular cavalry and the artillery. [20]Packenham. Thomas. ‘The Boer War’ page 193

British Cavalry.

The real irony for the British cavalry in South Africa was that it could have provided a real theatre of war for the demonstration of a well-trained mounted force. The great expanses of open terrain were ideally suited to wide sweeping raids in which the Boer could have been fought on his own terms from the very start. Not only this, but also the Boer battlefield tactics of digging themselves in and awaiting a frontal assault could have led to their undoing. Here was the chance to use the British cavalry to full effect. A mobile mounted force, together with a light and modern horse artillery could not only have turned the Boers out of every position they occupied but also, given enough strength, could have surrounded them completely and cut them off from any retreat to yet another defensive position.

No British cavalry commander in his right mind could have seriously considered a frontal charge against prepared positions, especially when they had witnessed the damage inflicted upon their own infantry. But it does seem that the nostalgic idea of massed cavalry going in full-out with the cold steel was never far from the minds of many generals who still nostalgically reflected back to the Charge of the Light Brigade, and Von Bredow’s Death Ride.

The only real attempt at a “classic” cavalry charge came at Elandslaagte on 21st October 1899. Here the Boer’s were attempting a drive on Ladysmith and the British managed to force them out of their position by the skilful use, for once, of the dismounted Imperial Light Horse together with three battalions of regular British infantry. However the Boers were heavily outnumbered, and upon retiring the Dragoon Guards and the 10th Lancers struck them in the flank as darkness was setting in. They made three charges sabreing and skewering at will, but the troopers found that the fight had lost some of its exhilaration. One of them wrote, ‘We went along sticking our lances through men-it is a terrible thing, but we have to do it…’ and a Dragoon corporal reported, ‘We just gave them a good dig as they lay.’ [21]Packenham. Thomas, ‘The Boer War’, page 79

There were cavalry commanders who had taken the trouble to train their men for dismounted action, and these were to prove of real value. The intervention of Lord Airlie with the 12th Lancers and a small detachment of mounted infantry on the flank at Magersfontein (11th December 1899) where a powerful turning movement by the Boer’s threatened to turn the disaster which had already overtaken the Highland Brigade, and would also have captured three British field batteries which had been in close support. Here Airlie was able to hold off a much superior enemy force because he had dismounted his men and posted them in excellent positions. When the Coldstream Guards finally arrived to take over, Airlie re-mounted his troopers and moved to another covering position. [22]McElwee, William, ‘The Art of War,’ page 227

With the arrival of the new Commander-in-Chief, Lord Roberts, “Bobs”, the British cavalry at last began to be used with some effect, and he recognised the need for a complete re-thinking in cavalry tactics, ‘I think we might have done better on more than one occasion if our Cavalry had been judiciously handled…Our Mounted Infantry has much improved of late, and I intend to see whether their employment in large bodies will bring about more satisfactory results’. [23]Carver, Field Marshal Lord, ‘The Boer War’ page 139. That Roberts was a voice in the wilderness as far as the general feelings of most cavalry officers were concerned, is shown by the remarks of Major (later Field Marshal) Douglas Haig, who being present on General French’s staff during the Boer War, considered that it was necessary to keep the cavalry in its old form because the “charge” was the ultimate aim of their training. [24]Ibid, page 259 Haig was still mooting these same sentiments even when he became Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force in 1915.

The Artillery.

As far as artillery was concerned the British army should not have been playing catch-up to any other country in the world. During the American Civil War British made breech- loading cannon had been in use, but never in great numbers. [25]Boatner.Mark, ‘Cassell’s Biographical Dictionary of the American Civil War’ page120 However by 1870, both Britain’s home army, and her army in India were fully equipped with breech-loading cannon, and although not perfect, owing to gas leakages around the breech, they were nevertheless a great improvement on the old muzzle-loading cannon of the past. Because of the poor performance of some of the breech-loading guns during active service in desert conditions, The New Ordnance Department, which had replaced the old Board of Ordnance in 1855, in its infinite wisdom, decided to rearm the whole of the Royal Artillery with muzzle-loading cannons in 1871. [26]McElwee.William, ‘The Art of War’, page 218 Not even the outstanding successes of the Krupp breech-loading guns used during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 persuaded the British army from retuning to a weapon already rejected by every other modern army. By 1880 there were only two breech-loading batteries left, and those were in the Army in India, and by 1890 even those had gone. [27]Major-General Sir C.Callwell and Major-General Sir J.Headlam, ‘The History of the Royal Artillery from the Indian Mutiny to the Great War’ Vol I, Appendix table C.

None of this took into account the development of new propellants, which gave a greater range and also enabled larger and larger shells to be fired. The barrels of artillery pieces had to be lengthened and tapered to fit and adjust to each change in modification, and before there was time to complete the whole change, along would come yet another improvement making these changes obsolete. [28]Ibid, page 161 What finally brought the army back to its senses were the problems pondered upon when considering an invasion of the British mainland. Here it was found that as battleship firepower had increased so the Garrison Artillery had to respond in like fashion in order to keep pace. As guns became larger so the difficulty of using muzzle-loaders became ever more apparent especially when gun crews had to climb up to swab out a massive casemate-installed cannon each time it was fired, and then reload at the muzzle. [29]Brodie.Bernard, ‘Sea Power in the Machine Age’ page 143 This was the deciding factor that made the British army once again revert to breech-loading cannon, but even with the outbreak of the Boer War in 1899 there were still one or two field batteries that had not been converted, like the Natal Field Artillery, which still used 7 ponder rifled muzzle-loaders. [30]Packenham. Thomas, ‘The Boer War’ page 90

The problems of facing the technological changes in armament was one thing, but how to use these new developments to better effect on the battlefield was quite another matter for the muddle-headed thinkers of the British high command. No testing had been carried out prior to the outbreak of war to compare the capabilities of the German made Krupp field gun with that of the “much improved” British 15-pounder howitzer, and it was only after the first disastrous battles with the Boer’s that it was realized that the Krupp cannon outranged the British artillery, in itself a damning indictment of the way the army went to war. [31]Packenham.Thomas, ‘The Boer War’ page 111 Not only this but the Boers had a weapon which the Ordnance Department had rejected as an unnecessary refinement in 1898, at that was the Krupp “Pom-Pom”, a weapon that the British soldier came to dread on the battlefields of South Africa. [32]Ibid, page 114On more than one occasion it had taken-out entire gun crews and groups of infantry with its rapid firing bursts of twenty or so one-pound shells. [33]McElwee. William, ‘The Art of War,’ page 220 It took the British Navy to come up with the answer, and that was in the form of rapidly improvised ships cannon mounted on a reinforced gun carriage, in itself a cumbersome weapon for use in mobile warfare. [34]These guns alone necessitated the use of over twenty Oxen each to move them to the battlefield. See Packenham, page 132 But even with this type of improvement the British Artillery still clung on to obsolete methods of deployment on the battlefield.

The artillery training hammered into commanders at Woolwich and Larkhill was still as archaic as those employed during the Crimean War, and even more disastrous, owing to the old dictum that ‘One gun is no gun.’ Thus when the British artillery went into action their field batteries were formed in neatly aligned rows of six guns, with their limbers and caissons arranged to the rear making them perfect targets for the Boer artillery. This in itself was bad enough but, even when smokeless powder had been introduced, the atmosphere and heat on the South African plains allowed for a haze to be set-up over each gun. This would not have been so bad for single cannon as this haze was not so discernable from a single gun, but when six or more were aligned and firing together, the Boer spotters soon homed-in on the heat-haze above the British batteries which developed after only a few minutes. [35]McElwee. William, ‘The Art of War,’ page 220 While the British tried to “comb” the Boer position at random, the single, well-sighted Boer cannons could pinpoint the British artillery positions and bring down devastatingly accurate fire.

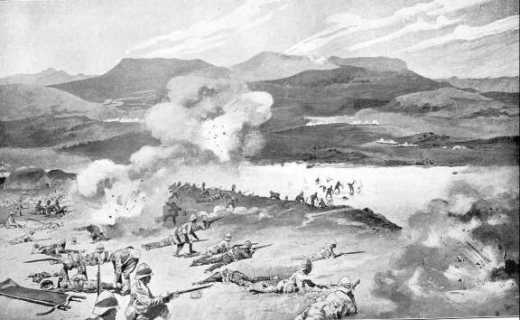

Another outdated tactic used by the British artillery commanders was to push their batteries too far forward. This praiseworthy, but ultimately suicidal mode of supporting an infantry attack is highlighted by the actions of Colonel C.J.Long at the Battle of Colenso (15th December 1899). Here Long, who had seen action at Omdurman fighting the Dervishes, and who considered that artillery should be used at ‘decisive range’, brought his twelve 15 pounder guns forward and unlimbered them at 1,250 yards from the concealed Boer riflemen. True to their training the gunners formed up and aligned their cannon in parade ground fashion, which would have earned them high praise at Woolwich, and they even managed to allow the British infantry to reach the outskirts of Colenso village. This, of course, was just what the Boers had intended, and once the foot soldiers where trapped inside the bottleneck of Colenso they opened such a devastating fire that within a matter of minutes Long was wounded and most of his command either suffered the same fate as their chief or were dead. As if this were not bad enough, but the sight of Long’s deserted guns standing out in the open diverted the British Commander in Chief, Sir Redvers Buller’s attention away from the main battle. He now forgot all about crossing the Tugela River and concentrated on recovering the guns, which was a failure, and only resulted in still more casualties and only two guns being brought back. [36]Pakenham.Thomas, ‘The Boer War’, page123-130 In his cable to London sent for public consumption. Buller presented an air of Victorian calm. He described the heroism of the attempts to save the guns, but he did not mention the collapse of his infantry. The one reference he did make was concerning Long’s “serious reverse” using the artillery to support the infantry attack, ‘This was, however, censored by the War Office.’ [37]Ibid, page 131

The strange thing about the use of artillery in the manner described above is that even with this glaring evidence before them the British army still continued to consider that close support was the most effective method of pinning down the enemy during an infantry attack. Colonel C.E. Callwell, in his book, ‘Small Wars, Their Principles and Practice’, although admitting that the Boer was an exceptional case, still maintained that, ‘the proper place for the guns is a little to the rear of the infantry firing line, whenever plunging fire is not required. The nearer they get to their work the better. If they are required to prepare the way for the infantry they should, as far as circumstances permit, be in action at the point where the infantry has come to a standstill, and this is the principle upon which, when the regular forces are acting on the offensive, the artillery usually does act if in efficient hands.’ [38]Callwell, Colonel C.E. ‘Small Wars’, page 430

Aftermath.

The account above is typical of the way in which the British army reverted to archaic methods which had proven inadequate in actual battlefield situations; indeed the more one reads about the army over the years since its inception, the more one sees that time and time again after a war, it seemed to fold- in on itself, and batten down the hatches, only emerging into the real world when a crisis was imminent. This is true of the High Command structure as within everything else. The Generals in charge of the British army in the Boer War were skilled in the principles of fighting savages and tribesmen. Years of Imperialist expansion had tested them against almost everything and every country where Britannia wished to plant her flag. The problem was that, although acquitting themselves well in small wars, where a little technology could be absorbed to help defeat the enemy, while allowing traditional methods of drill and training to win the day, now the boot was being placed firmly on the other foot, and it was the new improvements in machine-guns, rifles and artillery firepower, together with entrenchments and barbed-wire, that made it imperative to revaluate strategy as well as tactics.

Men like Lord Methuen, Sir John French, Sir Redvers Buller and Sir George White had their minds firmly fixed in the warfare of the 1870’s and 1880’s, and considered that defeating the Boer’s would be no different from disposing of the Zulus or the Dervishes, and because they had no experience of warfare on the continental standard, they naively expected the Boer’s to behave no differently from their normal foes.

Even with the arrival of Lord Roberts as commander-in chief of the British forces in South Africa, it was yet another case of employing a commander who had never before seen action against Europeans, or for that matter had never come up against an enemy armed with modern rifles and artillery; not only this but he had not been at the head of an army since 1880. What he soon grasped was that there were sever limitations to the accepted tactics of the British infantry when confronted by modern firepower and sophisticated entrenchments. [39]Packenham. Thomas, ‘The Boer War’, page 162 The main problem was that as soon as his back was turned his subordinates reverted to the same old methods that had cost them so dear at the commencement of the war. Kitchener was placed in the position of operational commander, and although he was a great organiser and administrator, he had little or no understanding of the tactical realities of modern warfare. His assaults on the Boer position at Modder River cost the British infantry over 1,000 unnecessary casualties, and only when Roberts came back to take over, were the infantry withdrawn and the artillery used to smother the Boer position with shellfire. [40]Ibid, page, 163 That Roberts understood the changes brought about by modern warfare becomes clear when one reads, ‘Success in war cannot be expected unless all ranks have been trained in peace to use their wits. Generals and Commanding Officers are therefore not only to encourage their subordinates in doing so by affording them constant opportunities of acting on their own responsibility, but they must also check all practices which interfere with the free exercise of their judgment, and will break down by every means in their power the paralysing habit of an unreasonable and mechanical adherence to the latter of the orders and to routine.’ [41]Quoted in. Michael Glovers,’Warfare from Waterloo to Mons’, page 223.

The Second Boer War was not a “small war” in which the British army was able to defeat and subdue a semi-backward enemy according to its training. The war in South Africa grew into a very serious conflict, which, while it brought volunteers from every part of the Empire to the assistance of the mother country, seriously strained its resources and exhibited to the military critics on the continent of Europe the numerous shortcomings of the British army. Although it was the Boers who had declared war, the sympathy of the continent was behind the Boers. The skill and tenacity with which a group of farmers had resisted the professional forces of a great Empire were very much admired. [42]Joll.James. ‘Europe Sine 1870’, page 95-97 To distant observers the war must have appeared as a contest between liberty and despotism, and in particular one would like to know what the feelings were in the United States when juxtaposed against their own struggle with British Colonialist/Imperialist expansion? Every victory of the Boers was received with rapturous enthusiasm by both the French and the Germans, and even the Tsar of Russia, whose own domestic government was no model for freedom, proposed a general alliance of the continental powers against Britain. [43]Ibid, page 98

As luck would have it Europe was powerless to intervene, but could only look on as Roberts and Kitchener retrieved the early reverses of the British army and wore down the Boer resistance. The fact was that the British Navy, and her supremacy at sea dominated the situation so that no continental power could challenge Britain in almost anything she chose to do. What it did kick-start however was to instil in the mind of the German Kaiser the need to meet Britain head on by creating a fleet that would match it. With over 400,000 troops tied down in South Africa, all of this makes one wonder what would have happened if the Germans had already built a fleet comparable with Britain’s, and what the consequences of Gavrilo Princip’s actions fourteen years earlier at Sarajevo would have done to make Britain reconsider her military commitments?

Given the power and resources of the British Empire there can be little doubt that the Boers were virtually doomed before the first shots were fired. That being said, one still has to consider how complacent the British army had become, and how faulty was its command structure, to say nothing of its strategical and tactical limitations when confronted with modern warfare. The phenomenon of a small but highly mobile force manoeuvring at will over the vast plains of South Africa was the precursor of the desert campaigns of 1940-43, and the sheer size of the British armies commitment to a “colonial” war can been seen as the proverbial “sledgehammer to crack a walnut.” Nevertheless the fact that the army was able to rectify many of its mistakes before any major conflict with a real modern state occurred shows that the lessons had sunk-in. The almost total lack of experience by the British generals in their handling of large bodies of men was an acute failing, and one sees here that this was due, in the main, to the almost total lack of infantry training grounds in England that could be used for division or corps manoeuvres, however one is still left with the feeling that, even allowing for improvements in the use of mass troop movements, the British high command was still not adaptable enough to take in new tactics.

What the Boer War did for the British army was to make it revaluate its methods and armaments, to say nothing of its status in the eyes of the general public. The old class-conscious British army was not destroyed, as Lord Wolseley had hoped. [44]Packenham.Thomas, ‘The Boer War’, page 288 On the other hand, ‘the War Office machine was given new premises, a new general staff, and a thorough overhaul. The Cabinet decided the partnership with the Commander-in-Chief was impossible and created a Chief of the Imperial General Staff instead, without warning the incumbent C-in-C, Roberts. He arrived one morning on 1904 to find that he had officially ceased to exist.’ [45]Ibid, page 288 With all of this “new broom”, the fact still remained that with the outbreak of war in 1914, the British Expeditionary Force still crossed over to the continent under a commander who had proven himself lacking in determination and tactical skills during the Boer War- this in itself is a damning indictment of the blinkered vision of the British army during this period.

Graham J.Morris

March 2004

Bibliography

| Barthop, Michael, | Anglo-Boer Wars, Blanford Press, England 1987. |

| Boatner, Mark, | Cassell’s Biographical Dictionary of the American Civil War 1861-1865, English Edition 1973. |

| Brodie, Bernard, | Sea Power in the Machine Age, Greenwood Press, New York 1943. |

| Beckett, I and Chandler, D, | The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army, England 1994 |

| Callwell, Colonel C.E., | Small Wars, Their Principles and Practice, Paperback Edition, University of Nebraska Press 1996. |

| Callwell, General C.E. and Headlam, General Sir J, | History of the Royal Artillery from the Indian Mutiny to the Great War, Volume I, Appendix, Royal Artillery Institute Woolwich 1931-1940. |

| Carver, Field Marshal the Lord, | The Boer War, The National Army Museum, London 1999. |

| McElwee, William, | The Art of War, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London 1974. |

| Glover, Michael, | Warfare from Waterloo to Mons, London 1980. |

| Jackson, Tabitha, | The Boer War, Channel 4 Books, England 1999. |

| Joll, James, | Europe Since 1870, Paperback Edition, Pelican Books, 1976. |

References

| ↑1 | From the ‘Battle of Magersfontein’, verse by Private Smith of the Black Watch December 1899. Quoted in, ‘Thomas Pakenham’s, ‘The Boer War’, page 115. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ‘The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army’. Page 184 |

| ↑3 | McElwee.William, ‘The Art of War’, page 214. McElwee also says that the firm of Gale and Polden had well over one hundred thousand books on military history in stock at the turn of the century page 335 |

| ↑4 | ‘The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army’, page 194 |

| ↑5 | Carver, Field Marshal Lord, ‘The Boer War’, Page 259-262 |

| ↑6 | Pakenham. Thomas, ‘The Boer War’, page 30 |

| ↑7 | Ibid, page 56 |

| ↑8 | McElwee.William. ‘The Art of War’, page 215 |

| ↑9 | A very interesting light is thrown upon this topic by Colonel C.E.Callwell in his work, ‘Small Wars”, page 51.Here, although accepting that the Boers were very good fighters, the author still considers that by “ambushing” a British column on the march, they used treachery to gain a victory. |

| ↑10 | McElwee. William, ‘The Art of War’, page 233. |

| ↑11 | Carver, Field Marshal Lord. ‘The Boer War’ page 20 |

| ↑12 | Colonel C.E.Callwell, ‘Small Wars’, page 399 |

| ↑13 | Jackson, Tabitha. ‘The Boer War’, page 58-59 |

| ↑14 | Ibid, page 59 |

| ↑15 | McElwee. William. ‘The Art of War’, page 234 |

| ↑16 | Ibid, page 235 |

| ↑17 | See both McElwee, page 223, and the very interesting account of how General Phil Sheridan was received in Europe in 1870 by various Prussian and English Generals. ‘Personal Memoirs of P.H.Sheridan Vol II page 403 |

| ↑18 | ‘The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army’, page 219 |

| ↑19 | McElwee. William. ‘The Art of War,’ page, 224 |

| ↑20 | Packenham. Thomas. ‘The Boer War’ page 193 |

| ↑21 | Packenham. Thomas, ‘The Boer War’, page 79 |

| ↑22 | McElwee, William, ‘The Art of War,’ page 227 |

| ↑23 | Carver, Field Marshal Lord, ‘The Boer War’ page 139. |

| ↑24 | Ibid, page 259 |

| ↑25 | Boatner.Mark, ‘Cassell’s Biographical Dictionary of the American Civil War’ page120 |

| ↑26 | McElwee.William, ‘The Art of War’, page 218 |

| ↑27 | Major-General Sir C.Callwell and Major-General Sir J.Headlam, ‘The History of the Royal Artillery from the Indian Mutiny to the Great War’ Vol I, Appendix table C. |

| ↑28 | Ibid, page 161 |

| ↑29 | Brodie.Bernard, ‘Sea Power in the Machine Age’ page 143 |

| ↑30 | Packenham. Thomas, ‘The Boer War’ page 90 |

| ↑31 | Packenham.Thomas, ‘The Boer War’ page 111 |

| ↑32 | Ibid, page 114 |

| ↑33, ↑35 | McElwee. William, ‘The Art of War,’ page 220 |

| ↑34 | These guns alone necessitated the use of over twenty Oxen each to move them to the battlefield. See Packenham, page 132 |

| ↑36 | Pakenham.Thomas, ‘The Boer War’, page123-130 |

| ↑37 | Ibid, page 131 |

| ↑38 | Callwell, Colonel C.E. ‘Small Wars’, page 430 |

| ↑39 | Packenham. Thomas, ‘The Boer War’, page 162 |

| ↑40 | Ibid, page, 163 |

| ↑41 | Quoted in. Michael Glovers,’Warfare from Waterloo to Mons’, page 223. |

| ↑42 | Joll.James. ‘Europe Sine 1870’, page 95-97 |

| ↑43 | Ibid, page 98 |

| ↑44 | Packenham.Thomas, ‘The Boer War’, page 288 |

| ↑45 | Ibid, page 288 |

my grandfather fought at colenso william henry sanders he was mentioned in dispatches and then he went on to fight in the great war. dont know where in france he fought, came home with trech foot and malaria buried in bristol in a military unmarked grave, my gran could not afford a funeral he was buried with military, flag organised by some kind person in the military hospital, grans name was vashti sanders and she could hardly affor to visit him many times there was also three daughters has well very young. would like to know more, i am william sanders grand son my father died three years ago he was 100 yrs he was only approx 10 or twelve when is father died so i did not get much information have a boer book and his name is mentioned in dispatches thats all i have would like to visit higrave if i knew the whatabouts hope some one could help me myself am now 76yrs bless you all william

Dear William,

Thank you for visiting the site and your interesting notes concerning your grandfather.

The best way to find information regarding your relation is to contact the Imperial War Museum in London. Their website has a contact section, but I think it better to either write or email them all the details you have regarding grandfather and they will probably have his regimental history.

Hope the above will be of help?

Best wishes,

Graham J.Morris (Battlefield Anomalies)

Your lack of intelligence shows by describing the boers: ” ….they had once again demonstrated that their bravery was matched by their stupidity in not adapting to modern tactics.”

The Boers had NO experience of fighting wars. They DIDN’T want to fight!! They were peaceful people who wanted to get on with their daily life and here come the barbarians and invade their country because of greed. What stupidity?? The Boers were brave and intelligent in their thinking. Trench war!! The British didn’t expect it. A small ‘army’ about the size of the population of Brighton against the British – and experienced army/country!! Wow, where is the stupidity coming in?

Thanks for your rude and rather childish comments.

You may be right, you may be wrong, but the Boers were themselves not adverse to greed. History show how they treated lesser mortals and how intolerant they could be.

As for Barbarians invading their country, that is just what the Boers did themselves to call it “Their Country” in the first place!

Please elaborate? How did the Boers treat ‘lesser mortals’ with intolerance different from their contemporaries at the time? What clearly defined and recognized countries did the Boers invade and when to establish ‘their country’?

Having re-read my old article I fail to see just what the heck you are banging-on about!

Re-read and you will find that none of your comments are justified.