Introduction

Although not directly dealing with battles and battlefields, I felt that I had to include this article on Napoleon to try and counter the outpourings of hero worship for the little Corsican that are flooding the military and historical websites. There seem to be people who actually believe that the “Great Thief of Europe” could do no wrong, and I even knew one fellow who had a shrine in his house dedicated to his memory-candles and all!

That his exploits are a rich and rewarding study in the art of military science and diplomatic manoeuvring is not in question. What does matter, to me at least, is that when one takes the trouble to study the man in depth it becomes clear that much of what he did was driven by his ego, while much of what he achieved fell apart almost as soon as his back was turned. I hope that this article will place the disaster of 1812 in its true perspective, and if it causes some folk to get hot under the collar than all I can say is, remember he was human.

With the capitulation of almost twenty thousand French troops at Bailen in Spain on July 28th 1808, the first hairline cracks began to appear in the Napoleonic Empire. It had become clear, but not to Napoleon himself, that Spanish nationalism was a new force capable of throwing a spanner into the Imperial works. A revolt in the Tyrol against his Bavarian allies, disjointed risings in Prussia, not much in themselves and easily subdued, were the first indications of stress and strain in the fabric of the Empire. The French themselves were also showing signs of sliding back into the habits of pre revolutionary decadence. Morality and virtue were at low ebb, and there was not much thought for tomorrow. [1]H.A.L. Fisher. History of Europe. Page 862.

Germany appeared to be well balanced and stable under Napoleon’s Confederation of the Rhine, and with Prussia forced to relinquish Westphalia and her Polish provinces, Austria excluded, and the German League of Princes having to conform to the directives issued in Paris, it looked as if stability had at last been achieved-not a bit of it!

‘The experiment was never tried in a time of peace. Napoleon’s Germany was from first to last an engine of war directed against England, and later Russia. Cut off from colonial trade, and by foreign armies of occupation who were not adverse to acts of pillage and plunder, drained of its able bodied men, bled white for money the Germans may be pardoned if, revising their friendly estimate of the French, they ended by wanting nothing more than a German nation strong enough to throw off the yoke and ever after to defend the German Rhine.’ [2]Ibid. Page 856-858

The Jews alone, after being liberated from the Ghetto and given equal citizenship with the German Gentiles, continued to regret the downfall of Napoleon. He was indeed their liberator. [3]Ibid. Page, 856. See also, Abram Leon Sachar, Napoleon and his Times, Page 296-300

It should also be noted that the spirit of the Revolution was being overshadowed by the Napoleonic image. At a conference which Napoleon had with the Emperor Alexander I of Russia in 1808, the French minister Talleyrand noted that now only Belgium and the Rhine frontier were attributed to the conquest of France, while further conquests were Napoleon’s alone. [4]H.A.L Fisher, History of Europe, Page 862 Also, while at Erfurt, Napoleon was keen to show the play ‘Mahomet’ by Voltaire, a play in which the hero seldom quits the stage! [5]Emil Ludwig, Napoleon. Page 309

As for Napoleon himself, by 1809 he was not in the prime of manhood. He was, in fact, ‘…middle-aged and out of condition from the soft life he had led…He was fat, which made him slightly effeminate in appearance. He did not stay on top of developments because of fatigue; his short attention span and lapses of memory may be accounted for similarly. Fatigue and his embarrassment at his appearance kept him from his usual close contact with troops.’

With all of the above being said, why oh why then did he embark on the top-heavy campaign against Holy Russia in 1812, without endeavouring to place his own house in order, especially when he had not managed to stabilise his hold on Spain, which sucked-in over 200,000 of his best troops, leaving him in the unenviable position of having to wage a war on two fronts? The answer is simple: he was such an egomaniac that he was under the impression that all was well. But while his prospects were darkening Napoleon bathed in the light of his own dazzling fortunes. His Empire “appeared” settled and on a permanently assured basis- in less than two years it was gone.

Napoleon had learned from experience during the Polish campaign of 1807 how Herculean were the labours before him; yet he addressed himself to the task with his usual confidence. Supplies and magazines were organised between the Elbe and the Vistula rivers, fortresses on the line of march were occupied and placed in readiness. Horses, horses and more horses were amassed for the cavalry, artillery and transports, to say nothing of the vast herds of cattle to supply food on-the-hoof. The very thought of providing fodder, grazing, oats, barley etc for such a gigantic ‘ark’ would have given a Texas rancher a heart attack, and should have been foreseen by Napoleon himself.

He was no mean mathematician, but even he could not comprehend the eating capacity of over 600,000 men and 300,000 animals. To give only one small example:

“Horses for cavalry, staff, regimental baggage, artillery, ammunition and commissariat-say, 150,000. Oats-each horse would require on average 8 lbs per day, total per week 8,400,000 lbs. Hay-for each horse 12 lbs per day, total per week 12,600,000 lbs. Now all this requires carriage. Supposing the magazines are 50 miles in the rear, and that each horse goes 100 miles per week, it would require for transport of ‘food only’ for the army 112,000 extra horses. This number must also be fed and therefore require a further 4,659 horses to carry their food plus their own. Oats at 8 lbs per day for each horse totals 9,799,356 lbs per week, making a grand total of 44,332,264 lbs per week.” [6]Otto von Pivka, Armies of 1812, Page 160. The extract is taken from “A view of the French Campaign in Russia in 1812”, published in Swansea, Wales in 1813.

It is certain that much thought and detail had been taken to accumulate large stocks of provisions at various locations so that supplies could be maintained, but it was the means of transport that were lacking to bring what was necessary in order to keep the army provisioned at the right times. The wagons used to carry these supplies proved unsuited to the Russian roads and, unlike other campaigns in Germany and Austria, no replacement wagons or horses could be found. Thus tons of supplies were simply dumped along the way. In his monumental tome, ‘Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia’, George F. Nafziger says that, “feeding the soldiers was reasonably well provided for.” [7]George F. Nafziger, Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia Page 87 However, Captain Dumonceau, who was with the Grand Armée in early June 1812, had a different tale to tell. “Mills were required for grinding tons of grain and ovens for baking such numbers of loaves; these were often lacking. This led to scarcity amongst the troops and then ensued the depredation of the local inhabitants.” [8]Brett-James, 1812, Napoleon’s Defeat in Russia, Page 26

Napoleon’s war machine began to fall apart soon after the campaign began, and diseases such as typhus and dysentery took there toll of thousands of men before they came within cannon shot of the Russians.

As the ponderous columns of the Grand Armée snaked their way across the river Niemen on the 24th-25th June 1812, Napoleon did not have much idea as to the actual strength or location of the Russian forces opposed to him. He overestimated their size from the outset, and for him this was a disastrous blunder. It was, in all probability, the cause of his overblown military build-up. If he had fewer mouths to feed he would have stood a better chance of the quick campaign he so much desired. Then why was he so keen on superior numbers? In Italy in 1796 he had manoeuvred with 40,000 men and defeated a larger enemy force; likewise in France in 1814 he was to do almost as much again against even greater odds. His method had always been, once his enemy was divided, to crush one wing of their army after the other. But the cumbersome multitude that he dragged along in his wake was symptomatic of his own increasing age and girth. His lust for power made him pile-up weight instead of equipping a more streamlined striking force. It was indeed, “The Fattening”. [9]Owen Connelly, Blundering to Glory, Page 151-152 The Emperor was no longer the lean general of Rivoli (January 14th 1797), and his army reflected, in a large mirror, his, and its own obesity.

Now and then there would still be a glimmer of Napoleon’s former military prowess, shown for example in the arrangements that he made, after establishing the whereabouts of the Russians, in taking up the central position at Vilna and endeavouring to contain the Russian general Barclay de Tolly’s First Army, while his younger brother Jerome and his step-son prince Eugene in the south moved to crush general Bagration’s Second Army. But the damper had been put on these plans by the sheer distance involved. [10]See Map enclosed and also, Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars, Page 46-51 In other campaigns Napoleon had been able to show himself at the crucial point, in Russia this proved impossible. Even those whom he put in command became too independent of one another to agree on a basic plan, and yet by the same token they were too dependent on Napoleon himself. He was the brain of the beast, but its limbs were arthritic.

At the outset of the campaign the Russian armies had no clear plans to stand firm or use the scorched earth policy against the invading hordes. Their main aim was survival, and if this meant retreat until they could show some kind of bold and equal front to Napoleon, then so be it. For his part therefore, Napoleon was forced to go along like a donkey following a carrot, and make his plans conform to the day-to-day decisions of the Russian generals. [11]Owen Connelly, Blundering to Glory, Page 162

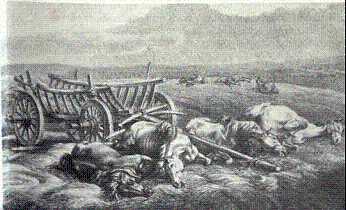

Vilna was now used as a recuperation point for the Grand Armée. The town fell to the French on 28th June. This breathing space was utilised by Napoleon, in the main to deal with political problems, instead of going after one or other of the Russian armies. But the French army was floundering, and the policy of living off the land alienated the population. [12]George F. Nafziger, Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia, Page 119 Thousands of horses had died and thousands of young soldiers lay dead along the army’s line of march. Trustworthy reports were lacking and Napoleon had to try to keep in touch with his auxiliaries, Prussian and Austrian, out on the wings. He stayed in Vilna for three weeks, far too long to be able to get on top of a swift campaign.

At Vitebsk Napoleon paused yet again (29th July-12th August) and still the Russians did not offer a full-scale engagement. Once again, for political expedience, he organised a provincial government and put on a military show for the benefit of the population.For their part the citizens of Vitebsk were more interested in the show moving on, and the looting to stop. Also while at Vitebsk Napoleon made a great deal of improvements to his administrative and medical service, but one wonders just how much true feeling for the welfare of his men went into all of this. After all it was he who had made the remark, “Such a man as I does not care a snap of the fingers for the lives of a million men!” [13]Emil Ludwig, Napoleon, Page 441

In conditions of alternating heat, rain, mud and dust the Grand Armée finally came up against the combined Russian forces at Smolensk (16th August). On the 17th the assault on the city began, and on the 18th the Russians had once more fallen back, but this time, owing to a failure in their command structure, their two armies had become separated. Now should have been the time for Napoleon to put an end to the campaign by falling upon one or the other isolated Russian armies and crushing it. Once again he was not in touch with his forward units. On the 19th August Barclay’s army was between the French corps of General Junot and Marshal Ney, having lost its direction during the retreat from Smolensk. Ney attacked but Junot did not budge owing to a mix-up in orders. [14]George F.Nafziger, Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia, Page 206 Thus the chance of knocking Barclay’s army out of the war was lost.

At Smolensk the French paused once more, while the flamboyant King of Naples, Joachim Murat plunged on ahead, doing little more than wearing out more horses. The question now was should the campaign be halted? Napoleon himself said at St Helena that he should never have left Smolensk, and that it was one of his greatest mistakes. The season was advanced and the city, or what was left of it, would have made an excellent place to draw breath and consolidate while awaiting events. Only the self-destroying ambition of Napoleon pushed him on in the belief that peace, on his own terms, awaited him in Moscow.

Even the Russians were by now becoming weary of retreat, and the Tsar, after coming under pressure at court, finally replaced Barclay as overall commander with Marshal Kutuzov, the veteran of Austerlitz. He was a patriot, the old champion of the army and a Russian, unlike the ‘German’ Barclay de Tolly. Also, for once, the new commander and the Tsar were in agreement, Moscow must be defended.

The position taken up by the Russians at Borodino was of no particular importance other than the fact that it straddled both the old and new Smolensk highways leading to Moscow. Even with the addition of hastily built earthworks it had serious weaknesses. Although the Russian right flank was virtually unassailable, the left flank, around the village of Utitza was not held in strength, and was in fact ‘in the air.’ [15]See Esposito and Elting, A Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars. Map 116 This point was drawn to Napoleon’s attention by Marshal Davout, his “right hand Marshal” who, if anyone could, would be able to roll-up the Russian line by a turning movement using the I and V army corps. [16]Christopher Duffy, Borodino, Page 84 Napoleon would have none of it, preferring instead to batter the Russians into submission head-on.

One can understand that Napoleon did not wish to see the Russians slip from his grasp yet again but, albeit with the benefit of hindsight, he should have taken Davout’s advice. It was indeed possible to outflank the Russian line, and by using his massive reserve of the Guard, together with his remaining corps, to have pinned their centre. One fails to see how the Russians could have slipped away once a general engagement was brought on. Also the strength of the Russian army is deceptive. The Moscow and Smolensk opolochenie (militia) were not good soldiers, even if their patriotism cannot be denied. The Cossacks were good light horsemen, but shied away from a full-blown engagement with anything other than a disorganised body of troops. [17]Ibid, Page 45 Therefore of the 120,000 men under Kutusov’s command at Borodino, only around 100,000 or so can be said to have been hard-core fighting men. On the French side all of Napoleon’s foreign contingents fought as bravely as their French counterparts. It was, under these circumstances, just a waste of good men and horses to throw them head-on against a foe who liked nothing better than a slogging match, and who, psychologically, were better prepared to engage in one.

The pious image of the Russian soldiers crossing themselves before the Icon of the “Black Virgin of Smolensk” can be juxtaposed by the Icon that Napoleon placed before the eyes of his own troops- a portrait of his own son, “The King of Rome”-some holy relic!

Even with the heads down battering ram approach, the Grand Armée was in a position towards mid-afternoon on the 7th of September 1812 to smash through the, by then disorganised and weakened Russian centre before they had a chance to close up and form a new line. Napoleon should have sent in the whole of his Guard, which numbered 20,000 fresh troops. Why have a ‘mass of decision’ if you cannot achieve a decision by holding it back?

As with all counterfactual arguments they are just that, what ifs. However there is one thing that can be said about Napoleon’s tactics (sic) at Borodino, and that is that he certainly earned the title to be given him three years later by the Duke of Wellington on the field of Waterloo that, “The man is only a pounder after all.” [18]David Howarth, A Near Run Thing, Page 126 For what it achieved, Borodino was no more than Eylau without the snow.

Peace was lacking even in Moscow, which was to have been Napoleon’s crowning glory to his campaign. He had nothing to show but a hollow victory. The conflagration that sprang up around him would light the torch of freedom from his rule, but still this little man clung to giant dreams, even when his only strategy was the strategy of retreat.

David Chandler says that, ‘ the problems of space, time and distance proved too great for one of the greatest military minds that ever existed, but it was the failure of a giant surrounded by pygmies!’ [19]David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon, Page 861 This maybe so, but Chandler does not mention the 29th Bulletin in his closing remarks on the Russian campaign, which must sum up the whole makeup of the man, ‘ … The cold, which arrived on the 7th (November), worsened suddenly; and on the nights of the 14th and 15th, the temperature was 16 and 18 degrees below freezing…Horses for the cavalry, artillery, and baggage train died every night, not by hundreds, but by thousands…We had to destroy a good part of our artillery as well as our munitions of food supplies…His Majesty’s health has never been better.’ [20]For the full Bulletin see Kafker and Laux, Napoleon and his Times, Page 240-245 Was Napoleon then blaming the ice and snow for the thousands of men lost during the summer? Of course he lost fewer men on the return trip, that is because he had fewer to lose! His troops gave him their all at the Berezina River (26th-29th November 1812) only to have him abandon them at Smorgoni (5th December) in order to return to Paris and secure his own reputation. In an interview with the Austrian minister Metternich, in May 1813, Napoleon gave the game away by saying, ‘The French cannot complain much of me. To spare them I have sacrificed the Germans and Poles.’ [21]Emil Ludwig, Napoleon, Page 441

Across the plains of Russia, thousands upon thousands of corpses of many nationalities lay as mute testament to their sacrifice at the alter of one man’s ego.

Graham J.Morris

January 28th 2004

Bibliography

| Connelly, Owen. | “Blundering to Glory,” Paperback Edition. SR Books 1984. |

| Cronin, Vincent. | “Napoleon,” William Collins and Son, London 1971. |

| Duffy, Christopher. | “Borodino,” Paperback Edition, Sphere Books, England 1972. |

| Esposito and Elting. | “A Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars,” West Point 1964. |

| Fisher, H.A.L. | “History of Europe,” Edward Arnold and Co Books, London 1936. |

| Howarth, David. | “A Near Run Thing,” Collins Books, London 1968. |

| James-Brett. | “1812, Napoleon’s Defeat in Russia,”Macmillan Books, London 1966. |

| Kafker, Frank A. and Laux, James M. | “Napoleon and his Times,”(Selected Interpretations) Paperback Edition, Krieger Press, U.S.A. 1991. |

| Ludwig, Emil. | “Napoleon,” George Allen and Unwin Ltd, London 1924. |

| Markham, Felix. | “Napoleon,” Weidenfled and Nicolson, London 1963. |

| Morris, William O’Connor. | “Napoleon”, G.P Putnam’s and Son, London 1893. |

| Nafziger, George F. | “Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia,” Presidio Press, U.S.A. 1988 |

| Nicolson, Nigel. | “Napoleon 1812,” England 1968. |

| Pivka, Otto von. | “Armies of 1812,” Patrick Stephens, Cambridge, England 1977. |

References

| ↑1 | H.A.L. Fisher. History of Europe. Page 862. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid. Page 856-858 |

| ↑3 | Ibid. Page, 856. See also, Abram Leon Sachar, Napoleon and his Times, Page 296-300 |

| ↑4 | H.A.L Fisher, History of Europe, Page 862 |

| ↑5 | Emil Ludwig, Napoleon. Page 309 |

| ↑6 | Otto von Pivka, Armies of 1812, Page 160. The extract is taken from “A view of the French Campaign in Russia in 1812”, published in Swansea, Wales in 1813. |

| ↑7 | George F. Nafziger, Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia Page 87 |

| ↑8 | Brett-James, 1812, Napoleon’s Defeat in Russia, Page 26 |

| ↑9 | Owen Connelly, Blundering to Glory, Page 151-152 |

| ↑10 | See Map enclosed and also, Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars, Page 46-51 |

| ↑11 | Owen Connelly, Blundering to Glory, Page 162 |

| ↑12 | George F. Nafziger, Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia, Page 119 |

| ↑13, ↑21 | Emil Ludwig, Napoleon, Page 441 |

| ↑14 | George F.Nafziger, Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia, Page 206 |

| ↑15 | See Esposito and Elting, A Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars. Map 116 |

| ↑16 | Christopher Duffy, Borodino, Page 84 |

| ↑17 | Ibid, Page 45 |

| ↑18 | David Howarth, A Near Run Thing, Page 126 |

| ↑19 | David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon, Page 861 |

| ↑20 | For the full Bulletin see Kafker and Laux, Napoleon and his Times, Page 240-245 |