September 17th 1862

Some observations concerning photographs and drawings used in depicting battle scenes.

Battlefields are mainly to be found in the rural areas of whatever country the conflict was fought, and are therefore subject to the changes in agricultural and domestic advancements that take place over the years. Roads are widened, ponds drained, woods are cleared and, in some cases, ground is altered by levelling and re-landscaping. Much of the Allied position at Waterloo was completely changed when the huge “Butte du Lion” mound was completed in 1826, and because there was no way of reproducing how the original landscape looked on photographs, the only real impression of the ground during the battle is to be found on the massive model, completed by Captain Siborne in 1838, and now on display at the National Army Museum, London.

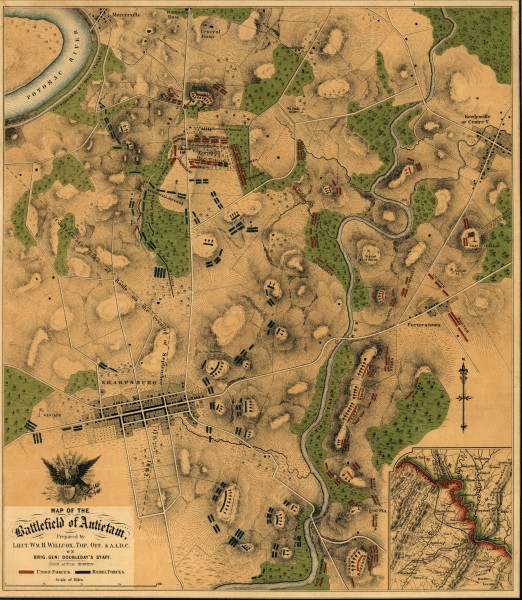

Thanks to the wonderful work carried out by the National Parks Service in America many of the major sites of the American Civil War have been preserved almost as they would have appeared during the actual battles. However, even with the best of intent, much of the terrain has either been changed due to natural causes – trees dying or being blown down by gales- and progress, new buildings being erected and roads widened, the latter to allow more accessibility to the public, which in itself causes still more problems owing to parking, toilets etc, and the need of possibly having to supply refreshment for visitors. The Visitors Centre on the battlefield of Sharpsburg (Antietam), built in 1962, was constructed with a large “fall –out” shelter beneath it, and despite its sympathetic design it still stands out like a carbuncle on the landscape. There is also the not – so – obvious factor that any landscape will be different ‘after’ a major engagement from how it looked before one took place!

Sharpsburg, in Maryland U.S.A., is an excellent example of how site preservation and the economic well being of the rural community can be managed without too many drastic changes being made (like the ubiquitous golf course) that might otherwise have relegated these historic fields and meadows to no more than just accounts and maps in books. With this being said the visitor should still keep an open mind when viewing all aspects of the landscape and trying to imagine how it looked as the turmoil of battle rolled across its now peaceful acres. Although I have never been able to visit the site myself, owing to financial constraints, I hope that the sketches and photographs herewith will help to show how aspects of a battlefield can change over time. I have also included some brief remarks concerning both photographic and artistic licence being used when portraying events that occurred during the course of the battle.

Major – General Jacob D. Cox, commanding a division in Burnside’s IX Corps (Union) describes how the battlefield looked on the afternoon of September 15th as the Union army began to arrive on the field:

We walked up the slope of the ridge before us, and looking westward from its crest the whole field of the coming battle was before us. Immediately in front the Antietam wound through the hollow, the hills rising gently on both sides. In the background on our left was the village of Sharpsburg, with fields enclosed by stone fences in front of it. At its right was a bit of wood (since known as the West Wood), with the little Dunker Church standing out white and sharp against it. Father to the right and left the scene was closed in by wooded ridges with open farm lands between, the whole making as pleasing and prosperous a landscape as can easily be imagined. [1]Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. II, page 630

Unfortunately there do not seem to be any modern photographs or panoramas of the “whole” battlefield, taken from a distant and elevated position that would show how the landscape looks today. Some excellent panorama photographs of selected areas of the site may be seen by visiting, “Behind the Stonewall,” The Antietam Battlefield, Cannonghost website. What we do have is a sketch, made during the course of the battle by one of the war artist present with the Union army, which shows just how open the ground looked (to the artist) leading up to the Confederate main position.

This sketch was made on the hill behind McClellan’s headquarters, which is seen in the hollow on the left. Sumner’s corps is seen in line of battle in the middle – ground, and Franklin’s is advancing in column to his support. The smoke in the left background is from a bursting Confederate caisson. The column of smoke is from the burning house and barn of S. Mumma, who gave the ground on which the Dunker Church stands, and after whom, in the Confederate reports, the church is frequently called “St Mumma’s.” On the right is the East Wood, in which is seen the smoke of the conflict between Mansfield and Jackson – Editors [2]Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. II, page 647.

It will be noted that, besides the trees surrounding various farms and houses, the only discernable wooded area (East Wood) appears in the right background of the above sketch. The West Wood, which would be further back and behind, is not visible (see map). We may note that the Union artillery stationed on the hill in front of the artist are not in action, but at such a distance from the main conflict would possibly be a rifled long range battery which has ceased firing as their own infantry close with the enemy. The Antietam Creek flows just in front of the Pry House, McClellan’s HQ, on the left – middle ground, not visible in this sketch.

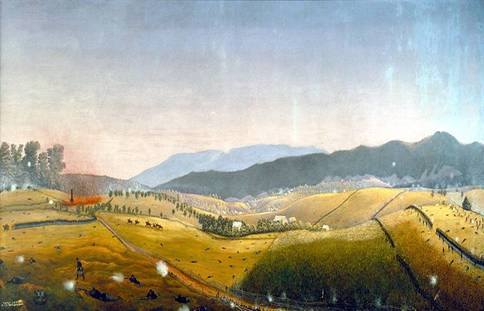

It is interesting to compare the landscape depicted above with that of another artist who was present at the battle, Captain James Hope. Hope was disabled by illness at Sharpsburg, but was assigned scouting and mapmaking duties. Sketches that he made during the battle were later used when he painted five large panoramas depicting various stages of the conflict, and although there may well be “too much blue sky and not enough smoke,” they give a good impression of how the battlefield looked (to him!) way back in 1862.

The above painting shows the battlefield looking north – east towards the Roulette Farm. The burning Mumma Farm is seen on the left, in front of which Union troops can be seen turning south to attack the Sunken Lane, afterwards known as Bloody Lane. The Union divisions of Richardson and French (II Corps) are seen on the right in line of battle, also advancing on the Sunken Lane. General McClellan and his staff can be seen riding in the middle ground. The artist shows more trees grouped and dotted across the middle ground and distance than there appear in the other sketch. The painting also stretches time and is intended to give a “general” impression of what took place over several hours. McClellan only rode out to view his forward position once during the whole battle, and that was at 2.00 pm in the afternoon. We should also take into account that, even with obvious clear skies, shadows in this painting give no real indication of the time of day.

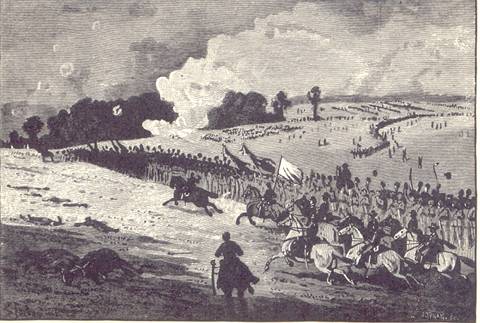

Another sketch by one of the war artists (Alfred R. Waud or Edwin Forbes) also shows McClellan riding his line of battle, this time with a few more staff than Hope depicts in his painting. Here we get a different impression of the battlefield. Where Hope has a billowing and undulating landscape, the sketch presents us with a reasonably level plain, the only visible depression being to the left of the picture where the dark cluster of trees slope gently down into a valley. There is certainly no sign of the steep – sided hills that so dominate Hope’s view of the field.

The ground depicted around the Roulette Farm is also worth considering in Hope’s painting in comparison with other sketches and photographs of this area of the battlefield. Hope shows the farm house and barns squatting snugly in a valley with steep hills rising on all sides, but if we look at another (Waud’s or Forbes’s) sketch of the battle things look very different (see below).

As we can see, the terrain is indeed undulating, but not as drastic as the miniature “alps” shown on the Hope painting. There are trees around the farm itself, but not the coppice – like cluster shown by Hope. Having said this, all artists go – their – own – way when it comes to interpretation of scenes, particularly if they consider that a more dramatic effect can be obtained by adding or subtracting some detail that will draw in the eye or has obstructed the overall composition of their work.

A photograph of the Roulette Farm, taken in 1862, presumably after the battle(?), gives us yet another view of the ground, and in particular the hills in the background, not as portrayed in the Hope painting(s), alpine ridges, but gently rolling hills. Once again we can see that, although there are trees surrounding the house, they are not in the same dense grouping shown by Hope. Of course, there is also the fact that, owing to battle damage, many of the trees that once stood around this part of the battlefield had been either completely destroyed during the course of the conflict or had been cut down later and never replaced? The Union army occupied the battlefield for several weeks after the battle and therefore would have “requisitioned” timber for campfires as well as for anything else required refurbishing with wood.

Another supple change to the battlefield can be seen at the Sunken Road, or “Bloody Lane.” The photographs taken by Alexander Gardener and James F.Gibson of Sharpsburg, exhibited in Mathew Brady’s New York studio, and entitled, The Dead at Antietam, show a very narrow, almost ditch – like track that appears to be no more than six or seven feet wide at its base if we use the bodies of the victims as a rough measuring guide. The lane was worn down to around two or three feet in depth and therefore the heads and shoulders of the defending Confederate infantry, who were using the lane as a natural rifle – pit, would have been exposed and so they had taken down the post and rail fences on either side to construct a rough breastwork facing the oncoming Union forces. How the lane looked before and during the battle we will never know, but the modern snake – rail fence which now encloses the lane on both sides maybe a little bit too exaggerated in order to add more “Civil War” effect to this part of the field (?) Some photographs taken twenty or so years after the battle could show a more realistic impression of how the Sunken Lane really looked “before” General D.H.Hill’s troops dismantled the fences.

Other photographs of the battlefield taken by Gardener are dubious to say the least, and one in particular seems to be a totally staged affair, using the dead as artistic props. It purports to show the Confederate dead on the west side of the Hagerstown Road, opposite the much contested and bloody cornfield (See below).

Take a close look at this photograph. It was taken on the 19th of September 1862, two days after the battle, and presumably these poor fellows have been left while the Union buried and tended to their own fallen comrades? All the bodies are lying on their backs as if turned over for either identification or to test if anyone of them was still breathing. The Hagerstown Road is on the right, between the two rows of fences on either side of the road. Fighting on this part of the battlefield was particularly severe. General Joe Hooker, commanding the Union First Army Corps stated that:

We had not proceeded far before I discovered that a heavy force of the enemy had taken possession of a corn – field (I have since learned about a thirty acre field), in my immediate front, and from the sun’s rays falling on their bayonets projecting above the corn could see that the field was filled with the enemy, with arms in their hands, standing apparently at ‘support arms.’ Instructions were immediately given for the assemblage of all my spare batteries near at hand, of which I think there were five or six, to spring into battery on the right of the field, and open with canister at once. In the time I am writing every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few moments before…My command followed the fugitives closely until we had passed the corn – field a quarter of a mile or more…[6]

Attack and counter attack ebbed and flowed over the cornfield and across the Hagerstown Road yet, in Gardner’s photograph, not a single rail is out of place on either side of the road. There are no signs of any small arms or artillery damage to any of the posts or rails of the fence, not even a mark of splintered wood, and this ground was supposedly not only within range of Hooker’s guns, but also of other Union batteries bought up to the outskirts of the East Wood!

We must remember that Gardner is now known for “staging” his compositions, in particular his, Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, taken after the battle of Gettysburg in 1863. Gardner moved the body of a dead Confederate and positioned it among the boulders in Devils Den for more dramatic effect, catering for the morbid and at times ghoulish obsession with sentimentality and death that prevailed during those times.

At Sharpsburg Gardner most probably had the corpses (which may have been already collected together for burial) deposited at an undamaged section of the road where he required them to stage his photograph. No other living person is in the frame, movement causing distortion and ghosting on the plates used at the time, and the ground itself seems remarkably fresh considering it was crossed and re – crossed by hundreds, if not thousands of men, together with artillery limbers and horses. I leave it to the readers of this article to make up their own minds.

In Conclusion.

I have been walking battlefields all over Europe for almost fifty years and I never expect to find a site perfectly preserved. If you are interested in finding out more about the topography of a battlefield, in particular ones that have no direct photographic evidence then try to search out old rural prints and paintings of the area. It is quite amazing how many small rural villages and towns have some of these either on the walls of bars and restaurants, or held in a local museum. Also try and find out if there is a local historian in the area, they usually know of, or have their own collection of, old prints and maps. Historical photographs of a site can be useful. Even if a battle took place long before the invention of the camera, one can still obtain a very good idea of the actual state of the ground before the introduction of the modern farming techniques and heavy industrialization. Remember, don’t just rely on military maps and books – use your eyes!

Graham Morris June 2010

[1] Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. II, page 630

[2] Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. II, page 647

[3] Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. II, page 648

[4] Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. II, page 641

[5] This photograph and the one below it are taken from, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. II, page 668

[6] Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. II page 639 – 640

Many thanks for your very detailed reply concerning my remarks concerning the Confederate dead along the Hagerstown Turnpike.

I bow to your superior knowledge regarding this battle but still find it very strange that – quick combat or not – the fence itself should still be in such good condition, allowing for the fact that Union long range “Parrot” rifled cannon had the road under fire for some time well before the said “firefight” took place?

Thanks for visiting my site!

Best Regards,

Graham

I have to disagree with your conclusions regarding the dead pictured adjacent to the Hagerstown Pike; they most certainly were killed in that position and were members of Starke’s Louisiana Brigade. The firefight that killed them lasted no more than five minutes. Additionally, it was an east-west firefight, whereas the majority of the morning cornfield battle was a north-south axis of combat. Also, there is almost certainly a union corpse on the top left hand of the photo just beyond the farm lane parallel to the Hagerstown pike. Last of all, there are roughly a dozen photographs of this group of bodies, you can clearly see the damage caused by the bullets and canister from Battery B from the post-fence rails. It was a quick combat, the Confederate line of battle was hit on three sides, and those men were killed faster than the time it took me to generate this message.