6th August 1870

“ In battle two moral activities rather than two material activities confront one another, and the stronger will carry the day…When the confidence one has placed in a superiority of material, incontestable for keeping the enemy at a distance, has been betrayed by the enemy’s determination to get to close quarters, braving your superior means of destruction, the enemy’s moral effect on you will be increased by all the confidence, and his moral activity will overwhelm your own…Hence it follows that the bayonet charge…in other words the forward march under fire, will every day have a correspondingly greater effect.”

Introduction.

When one takes into account that the French army was renown for its élan on the battlefield, then the actions fought during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) seem to reflect a change toward a more defensive attitude being adopted by many of her commanders. It could be argued that, given the rapidity of the Prussian advance, and the fact that French mobilization was carried out in such a chaotic manner, then her only option was to go over to the defensive, relying on the firepower of her new infantry rifle, the Chassepot, and her “secret weapon” the Mitrailleuse. In time of war however, things are never that simple. By selecting one of the battles from this fascinating campaign, in this case Spicheren, and using it as an example for comparison with other engagements that occurred during those fateful August days of 1870, it soon becomes clear that not only did the French high command choose to squander almost every opportunity that presented itself in their favour, but also, due to its total ineptitude both on and off the battlefield, also failed to capitalize on the equally pigheaded, and at times insubordinate conduct that also plagued the Prussian army.

The Road to War.

(Franz Xavier Winterhalter)

The Prussian victory over Austria at the Battle of Königgrätz (July 3rd 1866) had come not only as a blow, albeit as it turned out a kid-gloved one, to Austrian hegemony within the smaller German states, but the wind change that followed caused France to be rocked on her heels. Suddenly finding her own position within Europe challenged, the Emperor Napoleon III sought immediate guarantees of compensation in Belgium and on the left bank of the Rhine River, demands that were totally rejected by the Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck. [1]Howard. Michael, The Franco Prussian War, page 40. Napoleon himself was in poor health, suffering from bladder stones and lethargy. At times he could neither walk nor sleep, which so weakened him physically that his judgment and statesmanship were brought into question. [2]Gooch. G.P, The Second Empire, page 29. These problems, and the growing unrest within France, came to a head when a situation occurred that was in no way a precursor to war, and which should not even have been contemplated as an excuse for starting one.The British Ambassador to France, Lord Lyons noted in 1867 that, ‘The discontent is great and the distress among the working classes severe. There is no glitter at home or abroad to divert public attention, and the French have spent many years without the excitement of a change.’ In 1868 he went on to say, ‘Probably the wisest thing he (Napoleon III) could do would be to allow real Parliamentary government so as to give the Opposition hope of coming into office by less violent means than a revolution.’ [3]Quoted in Gooch. G.P, The Second Empire, page 28-29.

After the overthrow of Queen Isabella in 1868, the Spanish were casting around for a new monarch. During the summer of 1870 the throne was offered to the hereditary Prince of Hohenzollen-Sigmaringen, Leopold, whose brother Charles had recently accepted the crown of Rumania.

Under constant pressure from the Spanish President of the Council of Ministers, Marshal Prim, Leopold was showing no signs that he was enthusiastic about the proposal. Prim, who was secretly supported by Bismarck, next turned his attention on the Prussian King, William I, whom he hoped would help persuade Leopold to accept the offer. William himself was cool towards the idea, as he considered that the throne of Spain was, to say the least, precarious. Bismarck, who saw the possibilities of both military and commercial benefits being reaped once a Hohenzollen was firmly seated across the Pyrenees, entertained no such thoughts and began to talk Leopold’s father, Charles Antony, around into putting pressure on his son to take the job. Finally Leopold caved-in and, still somewhat reluctantly, accepted.

(Jean Adolphe Beauce)

As might be expected, the prospect of being placed between two Hohenzollen monarchs as in the jaws of a vice did not go down too well in France. Immediately outraged diplomatic outpourings began to be fired at poor Leopold who was only too happy to withdraw from the candidature, as he had no wish in creating an incident, and on 19th June 1870 he informed King William of his decision, and there it could have ended. However Napoleon still choose to recklessly press the issue by sending his Ambassador to the small spa town of Bad Ems where the Prussian monarch was taking the waters, with instructions to obtain a promise from William that Leopold would decline the offer were it to be renewed. William replied that he now considered the matter closed, but the French Ambassador, Benedetti asked for a second audience with the king in order to clear up some details, which William courteously declined stating that he had nothing more to say. [4]Gooch. G.P, The Second Empire, page 30 The famous “Ems Telegram” therefore contained no more than William’s refusal of further French demands concerning the candidacy of the Spanish crown. Bismarck was to claim in later life that he had edited the telegram to make it less conciliatory, but it is now clear that this is untrue and that the telegram had little influence on the decisions being taken in Paris. Not a single word of the telegram was altered, but it was abridged in such a way that it appeared as a slap in the face to the French, a fact that was compounded by it being circulated around Europe. As to the matter of Bismarck engineering the war the simple answer is probably that he was well aware of the risk involved, and was prepared to run it; that he believed the French had won the diplomatic contest is also true, but he was finally both surprised and relieved when they, at 11.20 a.m. on 19th July 1870, blundered into declaring war. [5]See the discussion concerning the telegram in, Conflict and Stability in the Development of Modern Europe, 1789-1970, Open University Press 1980.

The French Army

Being humiliated both politically and diplomatically after the collapse of Austria in 1866, the French had not become complacent with regard to their own military position, and fully realised that they may soon have to confront the Prussians in a stand up fight. Noting the fact that her professional army would be too small to confront the might of a much-enlarged Prussia, Napoleon had authorised Marshal Neil to raise the strength of the French forces from its mobilisation figure of 290,000 (in 1866) to at least 1,000,000 but: ‘The many schemes produced during the next eighteen months, including the one finally passed in January 1868 by an increasingly intransigent Corps Législatif, aimed at a front-line army on mobilisation of some 800,000 men, with a trained National Guard of at least 400,000 in reserve. Honestly implemented. This would have more than met Napoleon’s requirements. By 1875 France would have had a regular army of 800,000 on mobilisation, consisting of men who had served five years with the colours and four on permanent leave. This part of the programme, which would entail no increase of the annual contingent, was running smoothly with complete success when war came-five years too soon-in 1870.’ [6]McElwee.William, The Art of War, page 43

Things were still not altogether desperate, but with the death of Marshal Niel in August 1869, his post was filled by the competent, if less politically adroit, General Edmond Lebœuf, who coming under pressure from the Legislature was forced to make drastic cut backs in expenditure. However, by the summer of 1870 Lebœuf had available for active service almost 500,000 troops, which would give him, upon mobilisation, 300,000 men in three weeks. [7]Howard. Michael, The Franco-Prussian War, page 39 With their new infantry rifle, the chassepot, and their much-prized “secret weapon,” the Mitrailleuse, the French “appeared” ready to give the Prussians another lesson in Napoleonic warfare: ‘It was the tragedy of the French army, and of the French nation, that they did not realise in time that military organisation had entered into an entirely new age.’ [8]Ibid, page 39

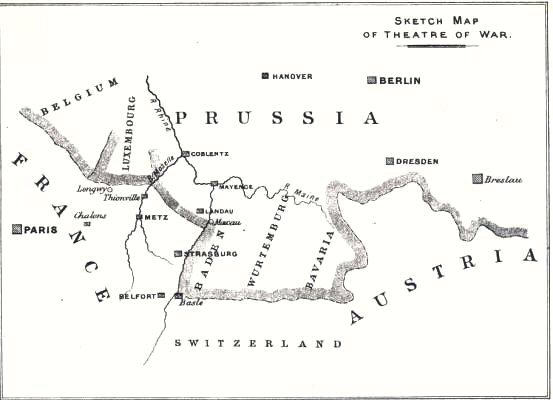

The French war plans were, to say the least, half-cocked and half-baked. Fully understanding that he would be outnumbered by the Prussians, Napoleon had decided to take the offensive before his own mobilisation was complete by a swift attack towards the east, hoping that he would be able to cause the South German States to reconsider their alliance with Prussia, but also win over the Austrians into entering the war on the side of France. To this end the French army was initially to be assembled with 150,000 men at Metz, 100,000 at Strasbourg, and a further 50,000 at Châlons. The first two armies would advance and unite before crossing the Rhine, and thereafter move rapidly into South Germany hoping to force those states into declaring their neutrality. After this the French would join with Austria and move on Berlin, while at the same time the French fleet would sail to threaten the Elbe River and the Baltic coast. [9]Fuller. General J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World, page 108-109

The only problem with this, what appeared to be a very feasible plan of operation, was that France were unable to cope with the immense logistical problems (most of her own creation) that were entailed in putting it into action: “In the supply depôts no camp-kettles, dishes and stoves; no canteens for the ambulances and no pack-saddles; in short no ambulances either for the divisions and corps. Up to the 7th (August) it was all but impossible to obtain a mule- litter for the wounded. That day thousands of wounded men were left in the hands of the enemy; no preparations had been made to get them away…If for four days our soldiers lived on the charity of the inhabitants, if our roads are littered with straggles dying of hunger, it is the administration which is to blame.” [10] Un ministére de la guerre de 24 jours, Palikao, pp. 57-59 Quoted in Fuller, page 109

(Walker collection)

This total confusion within the French administration, and the fact that Austria had also backed down from giving her support, caused a new plan to be hatched. On the 18th July the 4th Corps (Ladmirault); 2nd Corps (Frossard) and the 3rd Corps (Bazaine, who was in provisional command of the army until Napoleon arrived) were covering the area from Metz to the frontier. To the South, Marshal MacMahon with the 1st Corps was concentrating around Strasbourg. The 5th Corps under General Failly was stationed in and around Sarreguemines and Bitche where they formed a link between Metz and Strasbourg. The Imperial Guard (Bourbaki) was at Nancy, while the 7th Corps (Felix Douay) was forming around Belfort. On the 23rd July General Leboeuf, who was now on his way to join the army with the post of Chief-of-Staff to Napoleon, ordered a tighter grouping to the North, and to this end the Imperial Guard moved to Metz, while the 5th Corps moved closer to the left. While all this shuffling was taking place, Marshal Canrobert began to assemble the 6th Corps at Châlons. On 28th July Napoleon arrived at Metz to take command of the army.The only problem with this, what appeared to be a very feasible plan of operation, was that France were unable to cope with the immense logistical problems (most of her own creation) that were entailed in putting it into action: “In the supply depôts no camp-kettles, dishes and stoves; no canteens for the ambulances and no pack-saddles; in short no ambulances either for the divisions and corps. Up to the 7th (August) it was all but impossible to obtain a mule- litter for the wounded. That day thousands of wounded men were left in the hands of the enemy; no preparations had been made to get them away…If for four days our soldiers lived on the charity of the inhabitants, if our roads are littered with straggles dying of hunger, it is the administration which is to blame.” [11]Un ministére de la guerre de 24 jours, Palikao, pp. 57-59 Quoted in Fuller, page 109

The Prussians

The contributing factor to all Prussian success was their superior organisational skills, without which they could not have achieved such rapid and decisive concentrations of manpower and material on the battlefield. They also realised that supply and support was also a key element when manoeuvring masses of troops and equipment over large areas. No small part in these complicated and calculated undertakings was played by the Prussian Chief of Staff, Helmuth Carl Bernhard Graf von Moltke.

The credit for restructuring the Prussian army after its crushing defeat at the hands of the French in 1806 must go to military reformers such as Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Clasuewitz , however none of these could have realised the impact that rapid technological advances would make during the middle of the nineteenth century when, “…the varying pace of technical progress in different countries which, thanks to new inventions and their industrial exploitation, might give any one of the Great Powers a temporarily matchless potential superiority over all its neighbours…the ability of military authorities to perceive such an opportunity when it occurred and turn it to practical account strategically or tactically. This was essentially a new problem, and one which has persisted on commanders’ and general staffs’ considerations and calculations which would have been entirely irrelevant to Frederick the Great or Napoleon…” [12]McElwee.William, The Art of War, page 106

Although Prussia lagged far behind Britain in terms of the exploitation of her industrial potential, she nevertheless made rapid advances in railway development and in steel manufacturing. All of this was not lost on the Prussian military who soon saw the potential offered by the railways in rapid mobilisation and concentration of their forces. Also the new technology had enabled them to acquire, at least for a time, a weapon that was superior to those still being used in other European armies – the Needle Gun. [13]Ibid, page 107

These factors, together with the far reaching reforms put in place by Albrecht von Roon the Prussian Minister of War, gave Moltke the basic tools from which he was to develop the Prussian army into a formidable war machine. From the moment that he became Chief of Staff in 1857 he worked diligently and tirelessly training his staff and drafting and redrafting plans for rapid mobilisation. This entailed not only the study of railway timetables, but also the need to have detailed knowledge of rolling stock available as well as a prepared plan on hand to deal with any unforeseen emergency that would occur on the political scene. [14]Howard. Michael, The Franco-Prussian War, page 25 Although not perfect, as the campaigns of 1864, 1866 and 1870 would show, the Prussian system of continually updating and training, of studying and of analysing all aspects of military art and history certainly gave them a great advantage over their adversaries

In 1870, counting the army of the South German States, the Prussians could put almost 1,200,000 men in the field. These troops were organised into military Kreise (Circles’), which were based throughout the kingdom. Each Kreise became an Army Corp headquarters, and was concentrated in the main city of the area to which it was allocated, with divisional and regimental staffs grouped in close proximity in the outlying towns. This meant that the each corps was always permanently and geographically established where the commander in chief could contact it, and conscripts had no further to go to join their units than a day’s travel. The recruit, in turn would be officered by men from the same district, who were also familiar with their superiors at divisional and corps level, “Thus Scharnhorst (had) sought to perpetuate the Clausewitz ideal of war as an integral part of civilian life.” [15]McElwee. William, The Art of War, page 60

Prussian plans for war against France had been prepared back in 1867, and had been revised and updated each year. In principle the plan was simple, take the offensive and drive onto Paris seeking to destroy the enemy where and when they were met. [16]Fuller. General J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. III, page 107 The available forces for immediate operations against France consisted of:

- First Prussian Army, General von Steinmetz, VIIth and VIIIth Army Corps with one cavalry division; 60,000 men.

- Second Prussian Army, Prince Frederick Charles, IIIrd, IVth and Xth Army Corps, The Guard and two divisions of cavalry; 131,000 men.

- Third Prussian Army, Crown Prince of Prussia, V and XI Army Corps, I and II Bavarian Army Corps, one Württemberg and one Baden Divisions, one cavalry division; 130,000 men.

- Reserve, The King of Prussia, IX Army Corps and XII Saxon Army Corps; 60,000 men.

In addition there were the I, II and IV Army Corps with one Regular division and four Landwehr divisions watching the Danish coast and the Austrian frontier. [17]Fuller. General J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. III, page 107-108

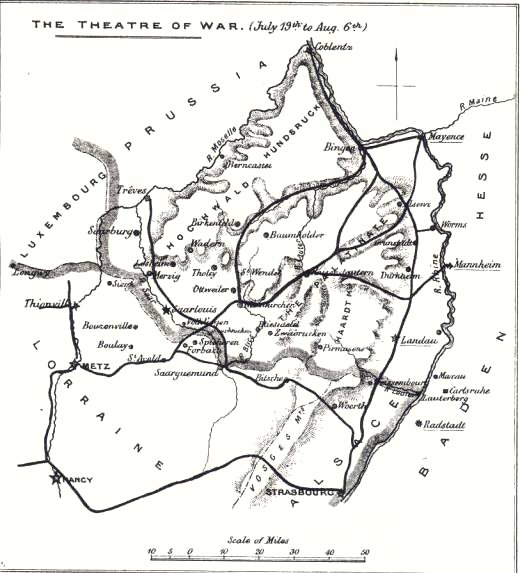

The Aufmarsch towards the frontier was carried out on a wide front between the Rhine and the Moselle with, on the right wing the First Army concentrating at Wadern and then moving on Saarlouis and the Moselle River below Metz. In the centre the Second Army, which now included the IX and XII Corps originally forming the Reserve, was to advance on Kaiserslautern and Neunkirchen and from thence on Saarbrücken, from where it was to move on Metz-Nancy on the upper Moselle. On the left wing, the Third Army, grouped around Landau, Rastadt and Karlsruhe were to advance on Strasbourg and occupy Alsace. [18]Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle, page 63-64

First Encounters.

(David Plant collection)

On 2nd August Frossard’s 2nd Corps drew up along the heights overlooking the Saarbrüken parade-ground and his artillery began to exchange a sporadic fire with the Prussian horse artillery battery which was stationed, together with four squadrons of cavalry and twelve companies of the 40th and 69th Regiments around the town. After a brief skirmish the Prussian commander in Saarbüruken, Colonel Pestel, who had orders to avoid bringing on a pitched battle, withdrew his force northwards to Lebach. [19]Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle, page 71Ineptitude and hesitation had quite literally, ‘…handed strategy over to the Paris mob. The boulevards were thronged, and shouts were raised demanding the instant invasion of Germany.’ [20]Fuller. General J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. III page 111 As usual, what the crowds in Paris demanded was considered as an indication of the mood of France as a whole, and on the 1st August Napoleon ordered a reconnaissance in force towards St Arvold and Saarbrücken, which entailed, on the left, the 3rd Corps moving in the direction of Völklingen, in the centre the 2nd Corps, accompanied by the Emperor and the young Prince Imperial moving over the Spicheren heights, and on the right 5th Corps crossing the river Saar at Sarreguemines.

With their usual flare for exaggeration the French press embellished events out of all proportion with what had happened in reality, ‘An entire German army corps had been destroyed. Saarbrücken had been reduced to rubble. “Our army,” said a Press announcement the following morning, “ has taken the offensive, and crossed the frontier and invaded Prussian territory. In spite of the strength of the enemy positions, a few of our battalions were enough to capture the heights which dominate Sarrbrücken.” In the capitol cheering crowds thronged the streets and the church bells rang. It was the first demonstration of public euphoria; and it was to be the last.’ [21]Ibid, page 71-72

While the French were celebrating a hollow triumph, Moltke was pressing on with the concentration of the Prussian armies. His forces now formed two wings. On the right, the Second Army under Frederick Charles containing the III, IV, IX, X, XII Corps, and the Prussian Guard, was advancing from the Rhine River towards Saarbrücken, while the First Army under General Steinmetz with the I, VII and VIII Corps were moving into line with the Second Army from the direction of the lower Moselle River towards Saarlouis, in all both armies numbered some 185,000 men. The left wing, commanded by the Prussian Crown Prince and containing the V, XI and the two Bavarian Corps and a division each from Baden and Württemberg, and numbering 125,000 men was advancing to threaten Alsace and Strasbourg, separated from the right wing by the Vosges Mountains. [22]Howard. Michael, The Franco-Prussian War, page 82

Totally unaware of the advance of the Prussian Third Army, on the 3rd August Marshal MacMahon had ordered the town of Weissemburg to be occupied by the division of General Abel Douay (brother of Felix), which numbered 8,000 men, and whose nearest support lay twenty miles away. Despite having sent cavalry patrols across the frontier, which proved to be as useless at reconnaissance as the French High Commander were at organising an effective plan of campaign, Douay deployed his division around the little town where he was engulfed by the Prussian Third Army. The General himself was killed and his shaken troops fell back to link up with MacMahon around Worth.

Moltke’s plan had been to unite the Prussian First and Second Armies behind the River Saar; there they would wait until the Third Army had crossed the Vosges Mountains. However General Steinmetz had other ideas, and proved that he did not have the slightest notion regarding Moltke’s plans.

(David Plant collection)

As soon as he received news of the fighting at Sarrbrücken, and despite strict orders from Moltke that the First Army was not to cross the Saar, but to coordinate its movements with the Second Army, Steinmetz, on the evening of the 5th August, ordered his entire force to the Saar. Here the 14th infantry division, who formed the First Army advance guard under General Arnold Karl von Kemeke, advancing on Saarbrücken on the morning of the 6th August, found the bridges still intact, and seeing the opportunity that this offered, pushed on to occupy the high ground just beyond the town. Frossard, who had withdrawn his 2nd Corps back about one mile to the Spicheren plateau, had abandoned these heights in order to take up what he considered to be a ‘position magnifique.’

The Battlefield

Sarrbrücken stood on the left bank of the River Saar, with two stone bridges connecting it to the twin town of St Johann on the opposite side. It was a prosperous and thriving community of some 20,000 inhabitants, and one of the main railway centres for coal distribution. Virtually surrounded by hills, the road running from St Johann on the north, cuts through the great Kollerthaler Forest to Lebach and St Wendel. At the village of St Arnual, about 1,800 meters above Saarbrücken, the river changes direction from north to west, where it is joined by a stream flowing from the west. This stream passes through an open valley, which runs parallel to that of the Saar River, but is much more confined, and named the Valley of St Arnual, which allowed for some unobstructed manoeuvring, the harvest already being gathered. Between Saarbrücken and the St Arnual Valley there rises an isolated ridge, which is divided into four separate crests. Further to the West stood the high ground upon which the drill-ground had been constructed for the garrison, while just above the Lower Bridge of the town rose the Reppertsberg. To the east stood the Winterberg, looking down on St. Arnual and the angle of the Saar River. In the space dividing the Winterberg and the Reppertsberg there rose a steep wooded knoll called the Nussberg. The Spicheren heights themselves dominated the surrounding countryside. To the east their slopes were covered by the thick timber of the Stiftswald and the Giferts Forests. To the west the slope dropped away into the Forbach- Stiring valley in which stood the imposing Stiring-Wendel ironworks, and through which ran the road to Metz. The entrance to this valley at the north was overlooked by a spur jutting out from the Spicheren heights, and known, from the reddish colour of the soil, as the Rotherberg. This particular feature overlooked the whole of the valley that lay between it and the recently evacuated heights around Sarrbrücken.The railway station stood at the north end of the town, just behind the centre of the Saarbrübrucken ridge, while the French Custom House and the Golden Bremm Inn lay just below the frowning Spicheren heights. [23]G.F.R Henderson, The Battle of Spicheren August 6th 1870, and the Events that Preceded it: a Study in Practical Tactics and War Training. Page 122-129

French Dispositions.

Frossard distributed his corps as follows: holding the right and centre was the division of General Laveaucoupet, deployed along the heights, with two companies entrenched on the Rotherberg. On the left General Vergé’s division occupied Stiring and the Forbach valley. General Bataille’s division was held back in reserve around Spicheren; in all, counting the corps cavalry and artillery, some 27,000 men with 90 guns. The map shows the positions of Frossard’s corps, and tells us much about his military attitude. By abandoning the high ground overlooking the Saar bridges (which he had not destroyed) he gave the enemy adequate room to establish a strong bridgehead, which in itself is a damming inditement on his military ability. He was, by training, first and foremost an engineer, and that he had imbibed the needs of modern warfare in which the spade complemented the rife, still does not excuse the fact that he totally failed to appreciate the full potential of his position being used not only for defensive purposes, but also for strong offensive action, which could have seriously jeopardised the whole Prussian plan of campaign. Not only this, but had he been adequately supported by other corps and divisions of the Army of Metz, most of whom were within no more than a few hours march of Spicheren, the well laid plans of Moltke could have been relegated to the rubbish heap.

The Battle.

If Frossard aired on the side of caution, Kameke threw restraint to the wind. After obtaining orders from his Corps commander, General von Zastrow to launch an attack on what he believed to be nothing more than a French rearguard, and without waiting for support, ordered his division forward. Not only had he failed to comprehend that, rather than a weak French rearguard, an entire army corps confronted him, but he also hit the part of the frontier where the French had massed more than one army corps. The four divisions of Bazaine’s 3rd Corps lay within fifteen miles of Spicheren. [24]Howard. Michael, The Franco-Prussian War, page 91

Just before noon on the morning of 6th August, General von François, commanding the 27th Brigade of Kameke’s division was ordered to clear the French artillery from the Rotherberg, and obviously sharing his commander’s view that nothing lay before him other than a weak holding force, François’s cannon began to lay down fire in prelude to his infantry advancing. Just after 1 p.m. he pushed out two battalions of the 74th Regiment on either flank, while the remaining two battalions moved towards the Rotherburg. Upon emerging from the tree line onto the open ground in front of the Spicheren heights the Prussians were greeted by heavy artillery and chassepot fire, together with the harsh Tak-Tak-Tak-Tak of the Mitrailleuse machine-gun as it barked into action, none of this doing any real damage to their company columns owing to the erratic nature of the French artillery fuses, and the fact that the Mitrailleuse was used in batteries like the artillery, rather than being pushed forward and dug-in among the infantry. However his flank battalions were forced to halt their forward progress in the Stiring valley on their left by the massed fire from Laveaucoupet’s division, and in front of Stiring Wendel on their right by a blizzard of lead and iron delivered by Vergé’s division. At the same time, although they had managed to reach the base of the Rotherberg the Prussians could do little more than take shelter there from French fire, which proved difficult to deliver owing to the steepness of the cliff face. [25]Howard. Michael, The Franco-Prussian War, page 94

By 2.30 p.m. François 27th Brigade was spread out over three miles and barely hanging on to the scanty ground it had thus far gained. Its losses were mounting and the troops much fatigued by their efforts. Kameke’s other brigade, the 28th was just crossing the Saar River with instructions to attack the French left rear, and to this end its commander, General von Woyna, had already sent the 53rd Regiment together with a half battalion of the 77th Regiment into the Saarbrücken Forest, while the rest of his brigade was still strung out in the rear.

Now should have been the moment for Frossard to launch a counterattack. With Kameke’s division spread so thinly over the ground, and his brigades separated from one another by the thickly wooded terrain, a strong blow delivered to the Prussian left flank would have forced them to retire, maybe it would even have caused them to route? Their gun line would have been overrun, and serious problems would have resulted in Prussian coordination once the French had regained the Saarbrücken Ridge. [26]G.F.R.Henderson, The Battle of Spicheren August 6th 1870, and Events that Preceded it: a Study in Practical Tactics and War Training. Page 151 The view of a recent French historian sums it up nicely:

‘What greater opportunity can be imagined? Frossard had only to throw himself on the Prussian formations and destroy them as they arrived one by one in the valley. But that did not happen. Frossard, an excellent engineer officer but a second-rate tactician, sat tight, and so succeeded in losing a battle which he should with minimum effort have won, while Bazaine, with 40,000 men close at hand, watched impassively the defeat of an army corps for no better reason than that its commander enjoyed a greater esteem than he in Imperial circles.’ [27]Quoted in, Ascoli.David, A Day of Battle, Mar-La-Tour 16th August 1870, page 87

Therefore the Prussians, who should have been taught a resounding lesson for their hastily conceived offensive, although still under considerable pressure from the French, were given time to bolster their overstretched front as more troops, and in particular more guns, were drawn to the sound of the fighting. As well as the remaining division of Zastrow’s VII Corps, the 13th, Frederick Charles, seething at having Steinmetz’s First Army blocking the road that he was meant to use, now ordered a general advance on Sarrbrücken.

At 3.30 p.m. Kameke, with every unit committed, but fully aware that help was on its way, launched a frontal attack against the Rotherberg using the Fusilier battalion of the 74th Regiment and three companies of the 39th, with General François leading. Opposed to them along the crest of the Rotherberg, and well dug-in, were the 10th Chasseurs and to their rear in support, a battery of Mitrailleuses. With remarkable courage and tenacity, the Prussians managed to scale the cliff face, and despite taking heavy causalities, managed to gain the crest, where they held on grimly in the face of mounting French attacks. General François was killed along with many of his men, but sustained by their own guns down in the valley, which raked the French position with an accurate and concentrated fire; the Prussians could not be forced from the heights. [28]Ibid, page 89

Not only had Kameke put all his available infantry and guns into the battle, he had also thrown in a squadron of Hussars to clear the French from the Rotherberg, a gesture which clearly shows his desperation. Just what these mounted troops were supposed to do when confronted by the steep sides of the cliff face which had caused their brothers in the infantry enough problems we will never know:

‘The Hussars were not long in discovering that their riding-school lessons did not include practice in crag-climbing, and they went back wiser than before…They saw before them a track which looked practicable, and they dashed on up, strewing the path with dead and living debris as they advanced. How near the summit one at least of them may have got I never knew till the next day, when I saw a dead hussar and a dead horse tumbled over into the ravine three-fourths of the way up. I saw them ride up. I never saw any of them ride back.’ [29]Forbes. Archibald, My Experiences of the War between France and Germany. Quoted in Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle, Mar-La-Tour 16th August 1870. page 89

As more and more Prussian batteries arrived on the field they inundated the French position. Every attempt to force Kameke’s small force from their precarious hold on the Rotherberg was smothered in shell fire, which also caused the French artillery to pull back out of range, their bronze muzzle loaders being no match for the Krupp breech loading cannon.

By 4.30 p.m. the first Prussian infantry reinforcements started to make their appearance. The 40th Regiment (VIII Corps, First Army) came in between the Rotherberg and the Gifert wood. Here they forced the French Chasseurs from the crest and linked up with Kameke’s line. To consolidate their hold on the position, and with great skill and courage, four guns were hauled up a rough track on the eastern face of the Rotherberg, these were soon joined by a further four cannon, also dragged up the steep track manually. Once in position they concentrated their fire on the village of Spicheren, about 1000 meters further south across a spur of open ground. Three separate French attacks were driven back with great loss but the Prussians found that they had only scratched the surface of Frossard’s main position, which lay before them on the high ground around Spicheren and Forbach, and to come to grips with the main French line they would have to cross over ground covered by artillery on the Pfaffenberg, which remained outside the range of their own guns. [30]Howard. Michael, The Franco-Prussian War, page 96

On the Prussian right Woyna’s 28th Brigade had become disorientated as it moved through the Saarbrücken Forest in an attempt to turn the French left. The 53rd Regiment, accompanied by the general himself, had conformed to his orders and attacked the high ground known as the Coal-pit Ridge, but suddenly discovering that the French position extended much further than he had anticipated, Woyna called up the 77th Regiment to bear more to the south-west. The two leading companies conformed, but the remainder of the First Battalion continued along the railway line where they became embroiled in the attack on Stiring Wendel. The other two battalions, just as they were about to wheel to the right, had received François 1.30 p.m. request for support, and had moved directly to the front, linking up with the 27th Brigade at around 3.00 p.m. The problem of control and command was so bad that Woyna was unaware, even at 4.30 p.m. that he had effectively been deprived of half of his brigade, and that what still remained was insufficient even to hold onto the ground he had gained, never mind being able to carry out any turning movement. [31]G.F.R Henderson, The Battle of Spicheren August 6th 1870, and the Events that Preceded it: a Study in Practical Tactics and War Training. Page 174

Frossard was well aware of the threat of a turning movement around his left flank. Vergé’s 1st Brigade (Valazé) had been holding its ground around the railway yards and factories of Stiring Wendel, but now became threatened on its left by the advance of the Prussian 13th Division moving down the Rossel valley in response to the sound of battle. Frossard had moved Vergé’s other brigade (Jolivet) from its position guarding his extreme left to bolster the defence of Stiring, while Bataille sent forward a regiment from his reserve division to Vergé’s assistance. Frossard also sent off an urgent message for help to General Metman, whose division had been ordered by Bazaine to take up a defensive (again!) position covering the road to St Avold, to move onto the ground vacated by Jolivet’s brigade -unfortunately for Frossard, Metman became as dilatory as Bazaine, and never got into action – thereafter the French launched a counterattack, which drove the Prussians back in some confusion, many retreating back to Saarbrücken. At 6.00 p.m. it appeared that the entire Prussian right wing was about to fall apart. [32]Howard. Michael, The Franco Prussian War, page 97

Fortunately for the Prussians, Constantin von Alvensleben had arrived earlier on the field with the forward elements of his III Corps (Second Army), and although he was outranked by both General Goeben and General Zastrow, his experience was such that his superiors were quite willing to leave operations in his capable hands. [33]Ibid, page 95

(David Plant collection)

Having committed his troops piecemeal to the centre and left as they came up, Alvensleben realized that, although he had no firm information concerning the state of the Prussian right wing, if the French now counterattacked in strength he could be forced back against the river. Therefore he decided to make another attempt to force the French to relinquish their hold on the Spicheren heights. To this end he sent six battalions forward in a direct assault from the Stiring Valley, endeavouring to come in against Laveaucoupet’s flank. Even here the Prussians found themselves in trouble. The first wave of the attack crumpled as it came under massed artillery and chassepot fire, while the second wave, coming up through the Spicheren Forest was stalled by a well executed hit-and-run withdrawal to the crest by Laveaucoupet’s flank guard, the Prussians only gaining the summit well after night had fallen. Here the French made a last bid to push their enemy from the Rotherberg and the Giferts Forest, but the attack was so disjointed and ill conceived that it achieved nothing. Finally at 7.30 p.m. Laveaucoupet concentrated his division in a tighter formation above Spicheren. [34]Howard. Michael, The Franco Prussian War, page 98

In the gathering darkness Frossard reluctantly decided to withdraw. Although his right wing had managed to blunt every attack thrown against it, the advance of General Glümer’s fresh Prussian division threatened his centre and left. To cover his retreat Frossard positioned 58 guns in one great battery around Spicheren, under the covering fire of which he managed to pull his corps back towards Sarreguemines. [35]Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle, Mars-La-Tour 16th August 1870, page 91

The French losses are reported as 2,000 killed and wounded, with a further 2,000 men missing, the majority of which were taken prisoner. The Prussians suffered over 4,400 casualties, which, allowing for their superiority in artillery, still demonstrates the effectiveness of the French chassepot.

On the same day (6th August), some 40 miles further to the east across the Vosges mountains the Prussian Third Army had defeated Marshal MacMahon at Froeschwiller, inflicting upon him the loss of almost twenty thousand men.

In concluding I herewith quote from William McElwee’s work, ‘The Art of War,’ which well sums up the whole misguided attitude of the French high command:

‘…the supreme irony of the campaign lay not in the failure of the French generals to exploit by counterattack the superiority which the Chassepot almost invariably asserted over the Prussian artillery. It lay in the fact that they had under their hand and failed to use effectively what was to be a war-winner of the future: the only machine gun [in Europe] then in existence.

Napoleon III had counted on the Mitrailleuse to redress the known inferiority of his artillery; and properly handled it might well have done so. It could be fired accurately up to a range of 2,000 yards at a rate of 150 rounds a minute. Used as an infantry weapon in the front line it could not only have made the already devastating fire of the Chassepot invincible in the infantry battle, but have forced the Prussian guns far enough back to allow the French batteries to move close enough to give their infantry overwhelming support. But the French chose to use it as an artillery weapon, organised in batteries and kept well behind the firing line. Its performance was, in consequence, bitterly disappointing. Only Canrobert properly appreciated its potentialities and later lamented that he had not been given them at St Privat where, he reckoned, they could have both completed the destruction of the Prussian Guard and enabled him to thin out his front line to provide a sufficient flank guard to frustrate the Saxon flanking attack which won the battle. So the most important of all the technological military achievements of the period was left entirely unexploited. [36]Mc Elwee. William, The Art of War, Page 146

Graham J.Morris

August 2005

Bibliography.

| Ascoli, David, | A Day of Battle, Mars-La-Tour 16th August 1870, Harrap Ltd, London, 1987. |

| Fuller, General J.F.C, | The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol III, London, 1957. |

| Gooch, G.P., | The Second Empire, Longmans, Green and Co, London, 1960. |

| Henderson, G.F.R., | The Battle of Spicheren, August 6th 1870, and the events which preceded it, London, 1891. |

| McElwee, William, | The Art of War Waterloo to Mons, London, 1974. |

| Patry, Léonce, Translated by Douglas Fermer, | The Reality of War, U.S.A. and England, 2001. |

Although a work of fiction, a great “feeling” for the period can be obtained by reading, The Debacle by Émile Zola, available in Penguin “Classics.”

The painting of General François leading the attack has not been given a source credit owing to the fact that I am unable to find either the artist or the collection in which it is stored. If it is thought that there has been a breach of copyright please contact me and I will make the necessary corrections.

References

| ↑1 | Howard. Michael, The Franco Prussian War, page 40. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gooch. G.P, The Second Empire, page 29. |

| ↑3 | Quoted in Gooch. G.P, The Second Empire, page 28-29. |

| ↑4 | Gooch. G.P, The Second Empire, page 30 |

| ↑5 | See the discussion concerning the telegram in, Conflict and Stability in the Development of Modern Europe, 1789-1970, Open University Press 1980. |

| ↑6 | McElwee.William, The Art of War, page 43 |

| ↑7 | Howard. Michael, The Franco-Prussian War, page 39 |

| ↑8 | Ibid, page 39 |

| ↑9 | Fuller. General J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World, page 108-109 |

| ↑10 | Un ministére de la guerre de 24 jours, Palikao, pp. 57-59 Quoted in Fuller, page 109 |

| ↑11 | Un ministére de la guerre de 24 jours, Palikao, pp. 57-59 Quoted in Fuller, page 109 |

| ↑12 | McElwee.William, The Art of War, page 106 |

| ↑13 | Ibid, page 107 |

| ↑14 | Howard. Michael, The Franco-Prussian War, page 25 |

| ↑15 | McElwee. William, The Art of War, page 60 |

| ↑16 | Fuller. General J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. III, page 107 |

| ↑17 | Fuller. General J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. III, page 107-108 |

| ↑18 | Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle, page 63-64 |

| ↑19 | Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle, page 71 |

| ↑20 | Fuller. General J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. III page 111 |

| ↑21 | Ibid, page 71-72 |

| ↑22 | Howard. Michael, The Franco-Prussian War, page 82 |

| ↑23 | G.F.R Henderson, The Battle of Spicheren August 6th 1870, and the Events that Preceded it: a Study in Practical Tactics and War Training. Page 122-129 |

| ↑24 | Howard. Michael, The Franco-Prussian War, page 91 |

| ↑25 | Howard. Michael, The Franco-Prussian War, page 94 |

| ↑26 | G.F.R.Henderson, The Battle of Spicheren August 6th 1870, and Events that Preceded it: a Study in Practical Tactics and War Training. Page 151 |

| ↑27 | Quoted in, Ascoli.David, A Day of Battle, Mar-La-Tour 16th August 1870, page 87 |

| ↑28 | Ibid, page 89 |

| ↑29 | Forbes. Archibald, My Experiences of the War between France and Germany. Quoted in Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle, Mar-La-Tour 16th August 1870. page 89 |

| ↑30 | Howard. Michael, The Franco-Prussian War, page 96 |

| ↑31 | G.F.R Henderson, The Battle of Spicheren August 6th 1870, and the Events that Preceded it: a Study in Practical Tactics and War Training. Page 174 |

| ↑32 | Howard. Michael, The Franco Prussian War, page 97 |

| ↑33 | Ibid, page 95 |

| ↑34 | Howard. Michael, The Franco Prussian War, page 98 |

| ↑35 | Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle, Mars-La-Tour 16th August 1870, page 91 |

| ↑36 | Mc Elwee. William, The Art of War, Page 146 |