I. Preliminaries; Vionville-Mars la Tour

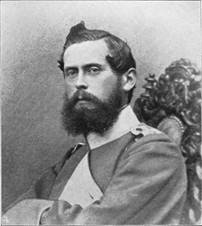

Oskar

In a sense it was a von Blumenthal who precipitated the successive battles of Vionville-Mars la Tour and Gravelotte-St. Privat. The Emperor Napoleon III’s army had been driven back from the German frontier into Metz, pursued by the German Second Army. The Emperor handed over command to Marshal Bazaine with orders to join the French army at Châlons, and departed. It was 15th. August, the Feast of the Assumption, and the Emperor’s birthday, which the French had scheduled for a victory parade in Berlin.

It was not obvious to the Germans what Bazaine was going to do; at first it looked as if he planned to make a stand before Metz, but the Germans were methodical in their scouting methods and sent out cavalry patrols to investigate. One of these, commanded by Rittmeister Count Oskar von Blumenthal, made its way in an anti-clockwise arc around Metz to the north, systematically entering villages and questioning the inhabitants. Eventually at Ars he found a frightened schoolmaster who had just come out of Metz, who said that “fifty thousand French troops had left Metz the previous evening taking the route Langeville, Moulins, Ste Ruffine, and the Route Imperiale through Gravelotte, Vionville and Mars la Tour.”

Oskar was 36, the second of four surviving children. When he was 17 he had cut short his schooling to join the Prussian Dragoon Guards, where his father, Count Bernhard commanded a squadron. The 1850s were peaceable times and his elder sister Asta von Pachelbl had married her first husband the same year. She widowed young and by now had just remarried to another cavalry officer in very different times; her new husband Friedrich von Pachelbl was also on campaign. There was another sister, Olga, still only 19; and his brother Count Alfons had only just returned to his regiment, the 7th King’s Grenadiers, after having been badly wounded in the Austro-Prussian War. He was somewhere to the south, in the Third Army which, under the Crown Prince, was being directed by its Chief of Staff, another member of the family, General (later Field Marshal) Leonhardt von Blumenthal.

Oskar was a seasoned fighter. After receiving his full commission he had been transferred to the 1st Silesian Dragoons and was on the staff of the German high command during the first of Bismarck’s wars, against Denmark. The Prussians had been the first to develop methodical staff work and to treat war as a much more intellectual process than hitherto. After the Danish war he was adjutant of a cavalry brigade but when the Austro-Prussian War broke in 1866 out he was on the Staff of the Second Army, whose Chief of Staff in that war the Leonhardt just mentioned. Oskar had seen plenty of action against the Austrians; he fought at the battles of Trautenau, Skalitz, Königinhof, Schweinschädel and the decisive victory at Königgrätz, where his brother was so badly wounded.

The following year he had married Wanda von Knobelsdorff, a colonel’s daughter, though the marriage was childless and would end in divorce a decade later.

Oskar had been decorated with the Order of the Red Eagle and given command of the 1st Squadron of the 9th Dragoons, as a reward for his conduct in the war against Austria. It was this squadron which now had in its hands the frightened schoolmaster of Ars, and it was Oskar who questioned him. It looked as if the French had escaped. Oskar’s report, which earned him the Iron Cross (IInd. Class), reached Prince Frederick Charles of Prussia, the “Red Prince,” commanding the Prussian Second Army, that same night.

Georg

To catch at least the tail-end of the retreating French, the Red Prince despatched General von Alvensleben’s IIIrd Corps, 30,000 men from Brandenburg, among them the young Lt. Georg von Blumenthal of the 8th Grenadiers, who was barely 20.

Georg and his brother Curt were the sons of a retired General, Louis von Blumenthal, brother of Leonhardt. Their father had seen action in all the Prussian army’s wars up to that point since the Berlin insurrection in 1848, but was now retired, living mostly with the family of his wife, Louisa von Burgsdorff at their estate at Hohenjesar, together with their young son Hans. Louisa’s great-grandfather Werner von Blumenthal had been a colonel in Frederick the Great’s time.

The two brothers were separated in different armies, Georg in the IIIrd, Curt in the IInd, but had seen their first action on the same day in different battles less than 10 days before, on 6th August, at Spicheren and Wörth respectively. At Wörth, a victory which Leonhardt had masterminded, Curt had been badly wounded and had spent the whole night on the bare earth shivering under a French horse-blanket, having directed the stretcher party to attend to one of his men first. The Crown Prince noted in his diary that, riding over the field of victory next day he had seen him there. He was on the mend and hoping to rejoin the fighting.

Georg, Curt and their cousin Friedrich von Blumenthal had all been at the cadet school in Berlin together. Georg’s regiment was brigaded with the 48th Foot to form the 9th Infantry Brigade under Major General von Döring, and he himself was the deputy adjutant of the brigade, itself part of General von Stülpnagel’s 5th Infantry Division.

The IIIrd Corps got close to the Route Imperiale and bivouacked for what was left of the night, sending out patrols to watch for the French. There were indeed troops still coming out of Metz, but it was impossible to tell if these were the rearguard or the van.

In the small hours General von Alvensleben headed towards the road near Vionville. Standing on the plateau, he realised that the 50,000 troops which Oskar had reported were in fact the vanguard, with behind them the whole of the French Army whose departure from Metz had been hampered by inward-bound heavy baggage.

Notwithstanding the odds, the gallant von Alvensleben attacked. The battle developed along the road between Vionville and Mars-la-Tour, as more and more troops on both sides got sucked into the action.

The English newspaper the Daily News reported: “The plain on which the battle was fought extends from the woods to the Verdun road, about one mile and a half, and is about three miles in length. On the French right the ground rises gently, and this was the key of the position, as the artillery, which would maintain itself there, swept the whole field. . . . From the woods to Rezonville, on the Verdun road, there is no cover, except one cottage midway on the Gorze road. This cottage was held by a half battery of French mitrailleuses, which did frightful execution in the Prussian ranks as they advanced from the wood.”

Georg was on of the 15,000 Prussians who now struggled across this plain against the fortified heights on the French right, which had been hastily strengthened by an earthwork. They were raked by the French battery as they repeatedly attempted to carry the all-important position. Baffled and repulsed, the Prussians still held on, until after three hours they drove the French off. Up the hill the Prussian horse artillery raced as the French artillery were galloping away to a hill on the right. They were only 500 yards apart, and for a long time an artillery duel ensued. The carnage was dreadful. At last the French moved off once more, this time to another hill farther off, the Prussians immediately taking up their vacant position. The conflict resumed.

Buddenbrock’s division of Brandenburgers advanced toward Mars-la-Tour, wheeled to the right, and, in the face of a rain of shot and shell, carried Flavigny and pushed on toward Vionville.

The 9th and 10th brigades in Stülpnagel’s division had been amalgamated in the struggle. It “fought its way to the front with desperate courage, but with varying fortune. One regiment in particular—the 52nd (formerly commanded by Georg’s father) —lost heavily in recovering some ground which had been wrested from it by the French. Its first battalion lost every one of its officers; the colours were passed from hand to hand as the bearers were successively shot down by the bullets of the chassepots, and the commander of the brigade, General von Döring fell mortally wounded.” Georg was walking just behind the von Döring. Cradling the general in his arms, he watched him die, and then, after ordering the body to be carried to the rear, resumed the advance with the brigade. For his coolness under fire he won the Iron Cross (IInd. Class).

As the fighting wore on, General von Alvensleben realised that a determined French attack would result in defeat. He ordered Gen. von Bredow’s XIIth Cavalry Brigade to forestall the French attack and silence the guns. Placing himself at the head of six squadrons of Uhlans and Cuirassiers, von Bredow cried “Koste es, was es wolle!” – “Cost what it may!” and launched his famous Death Ride, which swept the French artillery away, drove off their cavalry, and returned, having lost half its numbers. The success of this charge ensured the place of cavalry as an executive arm in modern armies for another half century.

Werner (the Dragoon)

The French fell back, or rather, fell forward on Mars-la-Tour. At about 3.30 p.m. Xth Corps at last arrived to take up position in defence of the ground before Mars-la-Tour. First in line were the Jägers, who started peppering the advancing French infantry. But the exhausted men of the 6th Division wavered. Seeing them fall back, General von Voigts-Rhetz decided to commit his remaining cavalry to a charge, and gave the order to General von Brandenburg. All he had were the 1st. Dragoon Guards and two squadrons of the 4th. Cuirassiers. The Dragoons’ Colonel von Auerswald formed them up. Among them was Rittmeister Prince Friedrich von Hohenzollern-Siegmaringen – brother of King Carol I of Roumania – and his best friend, 2nd Lt. Werner von Blumenthal.

Werner was the son of Count Werner von Blumenthal; his mother had died after giving birth to him in 1848. Unlike Oskar and Alfons, whose title of Count could be inherited by all their sons in their lifetime, this branch of the family held the title on condition that it could only be inherited by the eldest son on the death of his father, and only so long as they continued to own the beautiful estate of Suckow. Unfortunately Count Werner was short of money, and some years later sold Suckow, so that young Werner inherited neither the title nor the estate. But these troubles were in the future.

In the excitement of war with Austria, he had broken off his school education and taken the ensign’s exam and rushed to the front as a volunteer in the First Dragoon Guards, much like his distant cousin Oskar some years before. The very day he joined up he was off to the front. At Königgrätz he was in the charge against the Austrian 11th Uhlans which resulted in a famous cavalry mêlée.

Now it was time for another charge. It was clear that few would return, and General von Brandenburg called out to Colonel von Auerswald “I’m coming too!” Then they set off at a walk down either side of the road to Bruville. Passing through the Prussian 5th Jägers, they began to be shot at by the French 57th and 73rd regiments. The 13th Regiment was also able to shoot at them from the safety of the other side of a ravine. They caught the foremost French troops and halted their advance, but the suicidal attack cost the regiment nine officers killed, four wounded and one captured. Two of Bismarck’s sons, both troopers, were in the charge. Herbert, the elder, was wounded; his brother saved a comrade’s life. Covered in blood, Colonel von Auerswald led the survivors back from the charge and then, assembling them around him, addressed them: “Dragoons, you rode in well and bravely, I am delighted with you all; I am mortally wounded. God save his Majesty the King!” He died five days later. Werner and his friend Prince Friedrich were among the lucky officers left alive.

General von Rheinbaben now arrived with the 5th Cavalry Division, which he launched on the French flank in the grassy fields between the village and a stream called the Yron. The ensuing massed cavalry mêlée lasted to nightfall. It would still have been possible for the French to escape to Châlons, but Bazaine ordered the troops who had been engaged at Mars-la-Tour to fall back on his main army at Gravelotte. For this order, French conspiracy theorists would soon accuse him of treason, not only to his Emperor, whose fate could already be guessed, but to France herself. It is more probable that he was gripped by the same mental paralysis which had afflicted the entire French high command from the beginning. He was also fat and sluggish; but it had nothing to do with cowardice for he did not shrink from the next, much greater, battle.

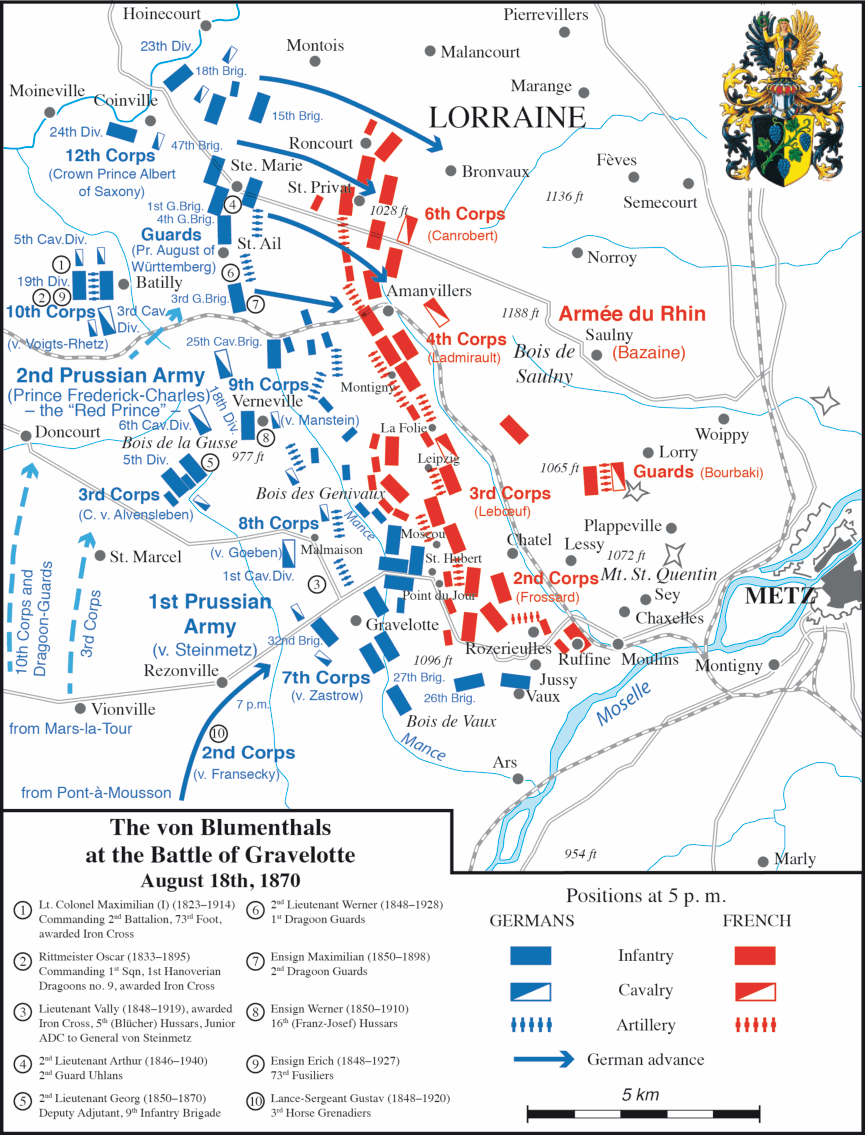

II. Gravelotte

On 18th August 1870 the battle of Gravelotte began when the commander of the German Second Army, Prince Frederick Charles, known as the Red Prince, ordered an advance on the French position, which meant that the men had to step over dead bodies in the ploughed fields before Mars-la-Tour where they had just fought. Artillery drivers could hear skulls cracking under the wheels. This time both sides knew roughly where the other was, though the Red Prince at first thought he was chasing the rearguard of the French, whom he assumed to be falling back on Metz. It was only when Moltke came onto the scene and the various Prussian forces (apart from the Crown Prince’s Third Army) concentrated, that the fact the French had a prepared position became evident. The ten Blumenthals who would fight at the great struggle of Gravelotte-St. Privat would be present on almost every part of it.

Vally

General von Steinmetz was in command of the First Army, and now for the first time was with it at the front. Lt. Vally von Blumenthal was attached to his staff a few days before the battle as Ordnanzoffizier, a Junior ADC. Vally’s unusual Christian name was chosen by his heartbroken father Herrmann after his beloved wife Valeska von Krockow died giving birth to their only child. Herrmann had been one of five brothers and four sisters. Of the brothers, two (Robert and Maximilian) were distinguished, two (Ludwig and Herrmann) undistinguished and one, Wilhelm died as a cadet aged 17. Of the sisters, only one married, to an infantry captain. The eldest brother, Robert, was the longest-serving governor of Danzig in history, during a turbulent period. The youngest, Maximilian, became a Major-General and took part in this battle. Herrmann, after twenty years’ peacetime service in a run-of-the-mill infantry regiment, never made it to captain. He left the army after his wife’s death and became reclusive, living in Pomerania, mostly in Stolp either at his mother Louise (née von Hartmann)’s house, or sometimes at the nearby estate of Schlönwitz which he acquired through his wife’s inheritance. Left largely in the hands of his maiden aunts Vally lacked male company and was left to fend largely for himself. Bismarck, whose wife was a friend of the von Blumenthals, was sorry for the lad and used to have him over on Sundays, and thus called him “My ‘Sunday’s Child’”. He joined the Lichtenfeld Corps of Cadets in Berlin and went into the Blücher Hussars just in time to go to war against Austria. He fought at Münchengrätz, at the furious engagement at Gitschin and at Königgrätz where he was commissioned in the field. He remembered that six-week war as a “picnic”: “We all got hatfuls of medals and no-one was killed.” In this war, Gravelotte was to be his first action.

Maximilian (the elder) and Erich

On the right wing, in the woods to the right of Gravelotte, which lay on part of the previous day’s battlefield, in front of Ars, were the 73rd Fusiliers, where Vally’s uncle Maximilian and cousin Erich were serving. As a Lt. Colonel, Maximilian commanded his battalion while his late brother Ludwig’s polite and delicate 22-year-old nephew Ensign Erich von Blumenthal carried the colour.

Maximilian’s father had been a colonel of dragoons during the Napoleonic Wars. He himself had been a major commanding a company of the 1st Grenadiers during the Austro-Prussian War where he had fought at Trautenau and Königgrätz and been rewarded with the Order of the Red Eagle and command of a battalion of the 73rd Fusiliers. By now he was 47 and had only two years before married Thekla von Puttkamer; they lived on her estate at Grünwalde but so far had no children. For his nephew Erich, Gravelotte would be his first and last action, for though he lived into the late 1920s, he fell ill after the battle and retired from the army.

The regiment was connected via the Mance Valley with VIII Corps, which Moltke had transferred from the First to the Second Army, and occupied Gravelotte itself. Behind, II Corps occupied Rezonville.

Gustav

Slightly behind the village of Rezonville were the 3rd Dragoons, where the most junior member of the family, Gustav von Blumenthal was a lance-serjeant, shortly to be commissioned for bravery in the face of the enemy.

Gustav was another nephew of Leonhardt’s and thus the first cousin of Georg and Curt. His father Gustav had been medically disqualified from the army having scored the top marks at the Cadet School in Berlin; and had then had to watch his brothers Ludwig and Leonhardt follow glittering military careers. To some extent he made up by being equally brilliant at managing his family properties, to which he added enormously, so that by the end of the 1870s he owned the estates of Segenthin (where the younger Gustav was born), Deutsch-Puddiger, Vehlow and Tonowo. Now three of the elder Gustav’s four sons were about to see action, the fourth being too young.

Young Gustav had not entirely intended to pursue a military career. Although he went to Cadet School and served in the army as a part-time volunteer, encouraged by his uncle Leonhardt, he was really being groomed to manage his father’s estates. However, when war loomed in 1870 he signed up and went to the front, as did his brothers Arthur and Werner, who were in this battle.

In this part of the line, the stench of rotting corpses was nauseating.

Further over to the left, at a distance of about four miles, III Corps occupied the Prussian centre, nestling among the woods, resting their left flank on the village of Verneville. Here now was the 9th Brigade, where Georg was now adjutant to a new commander.

On the left wing, at first facing the forward French position at St Marie, in front of St Privat, was the Corps of Guards, which was taking the ground in the approach to the nearer village of St. Ail. Out of sight was the Saxon Corps, whose objective was to outflank French right. The original intention was simply to encircle them and contain them. However, it did not become apparent, until after the attack on the French left had started, how very far the French right extended, and this forced the Saxons into a longer and more tiring march than expected, also causing delays in the development of the Guards’ attack on Ste Marie.

The French faced the Prussians from higher ground, with their rear against a convenient road and railways, making communications easy. They had set up field fortifications and entrenchments which incorporated a string of farm buildings, at Jussy, Point du Jour, St. Hubert, Moscou (named after the events of 1812), Leipzig (after 1806), La Follie, Montigny la Grange and the villages of Amanvillers and St. Privat. At the last minute they had occupied Ste. Marie, a solidly built place with excellent walls, but which they failed to make properly defensible with barricades. Before most of the French lines lay open ground, like “a natural open glacis” as the American General Sheridan, who was there, observed.

The Prussian high command was unsure what to do next. General von Roon argued that attacking here would achieve nothing; the French were already cut off from their supplies and, once the Saxons had gone round, would soon be surrounded. As before, events were decided lower down the hierarchy. General von Manstein started an artillery duel in the centre and directed his 18th division to get ready for an advance. His guns worked forward with the infantry towards Moscou, but the return fire was deadly.

Old General von Steinmetz heard the cannonade and now committed an unforgivable act of insubordination. He not only recklessly sent VII Corps to support von Manstein’s assault, he also sent in von Gröben’s VIII Corps, which he no longer commanded. They brought their artillery to bear, enfilading the French lines and taking the pressure off von Manstein’s guns. So far so good. But now von Gröben’s two principal divisons, the 15th and 16th, were brought up. The 15th. started forward, and before long was taking terrible casualties.

Then VII Corps came up. From General von Steinmetz’s headquarters, Vally was able to watch his cousins Maximilian and Erich’s regiment, the 73rd Fusiliers, as it toiled up the cobbled path from Gravelotte before descending into the Mance Ravine. From here, it was an uphill march into the thick of the French defences between Moscou and Point du Jour. It was a cross-fire of Mitrailleuses, Chassepot and canister. The Corps wavered and fled. Seeing this, the King himself rode down with General Sheridan and Moltke. Passing through Gravelotte, they ran into General von Steinmetz. “Why are the men retreating?” demanded the King, who had been swearing at the fugitives as he passed them. “Their officers are all dead, Your Majesty.” Tempers were flaring, and the King said the fleeing men were all cowards. Moltke would not have this. “But Your Majesty, “ he exclaimed, “they are dying for you like heroes.” “I’ll be the judge of that,” said the King, who was certainly no coward himself. Moltke angrily turned his horse round and left the King, practically alone in the foremost part of the front. Perhaps the King saw that von Steinmetz was exaggerating, for there were still plenty of officers fit for duty – neither Maximilian nor his nephew Erich had been hurt, for example.

At the other end of the line, the Prussians were still forming up. The Guards were ready around Amanvillers, waiting for the Saxons. At about the time von Steinmetz’s Corps was in mid flight, the Guards and Saxons began a tremendous bombardment on the French right at St. Privat. The Guards were preparing to take Ste Marie, so as to create a link with the Saxons, and seeing this the French sallied out to take the unoccupied village of St. Ail. There was a race for it, which the Guard Light Infantry won; then they took Ste Marie.

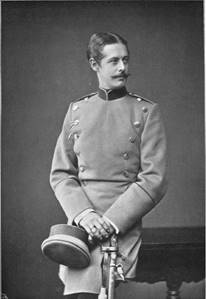

The Younger Maximilian (Dragoon Guards)

From here the Guards formed up to face the French around St. Privat squarely. Behind the village were the 3rd Guards Cavalry Brigade, consisting of the 1st and 2nd Dragoon Guards, where Werner, who had already fought at Vionville the day before, and his cousin Ensign Maximilian von Blumenthal were respectively serving.

Maximilian’s father Adalbert was the younger brother of Werner’s father, Count Werner. He was born at the charming estate of Varzin, which the von Blumenthals later sold to Bismarck, had been mostly educated at home and had only joined the army the year before aged 19.

Arthur

Just behind Werner and Maximilian in the Dragoons was 2nd. Lt. Arthur von Blumenthal’s regiment, the 2nd Guard Uhlans, in a hollow by St. Ail, occupying the ground between the Guards and Xth Corps.

Gustav’s brother Arthur was born in Berlin in the family home of his mother, Anna von Arnim in 1846, and went into the First Foot Guards. Aged twenty he took part in the war against Austrian and fought at Soor and Königinhof and at Königrätz he was wounded in the head by a grenade splinter during the celebrated storming of the heights of Chlum, and was decorated. After the Austrian War he transferred to the cavalry and was now in a squadron of the Uhlans, stationed only slightly in front of Oskar’s regiment, the 9th Dragoon Guards, formed up beside the village of Batilly.

Werner (the Hussar)

The Saxon XIIth Corps began to appear on the extreme left, enfilading the French around Roncourt. Here Gustav and Arthur’s brother, Ensign Werner von Blumenthal (not to be confused with his cousin Werner in the Dragoon Guards) carried the colour of the 16th Hussars. Too young to fight in the Austro-Prussian War, this was his first action.

This was the moment when the outcome of the battle hung on the balance. If the French followed up their success at Gravelotte, they would win; if not, they would lose at St. Privat. The Guards’ artillery now came to bear on the French positions, and the combined effect of the bombardment from both Prussian armies was terrible, a foretaste of the Trenches of WWI and the Blitz of WWII.

The French artillery did not make it easy for the Prussian gunners, who had to work forward, limbering up and unlimbering again. Anyone who has seen the Royal Horse Artillery firing the Queen’s Salute at Hyde Park can imagine how exhausting this was. The ammunition wagons had also to be brought up and the supply of shells synchronised. On the right wing, it was Vally’s task as junior ADC to ensure the details, riding back and forth under fire to see that the roads were kept clear by other units, who were themselves eager to press along. For his work he earned the Iron Cross.

On the other wing Canrobert was alarmed to see the Saxons arriving on his right, but Bazaine ignored his pleas for supplies and reinforcements. Many of his guns were now out of action, but this proved a godsend to the French, for the silence of his artillery tempted General von Württemberg to launch the Guards into a premature attack, up the steep slope to Gravelotte. The defenders concentrated on them until they began to reel; officers had to drive their men back into the fight at sword point. But then at last the Saxons engaged, and the French right wing collapsed, unbelievably, because twenty men per company were detached to cook dinner!

As the French right cracked, so did the centre; but even now victory was not assured. The VIIth and VIIIth Corps were exhausted and suffering heavily from the struggle up the Mance Ravine. Maximilian and Erich’s unit, the 73rd Fusiliers, was caught in a cross-fire which was now made worse by Prussian guns arriving at Gravelotte who bombarded the whole area, unaware that their own men were mixed into the French position. Panic started to set in, and for the second time knots of Prussian soldiers ran back past their own king shouting “All is lost!” This did not, however, go for Maximilian’s battalion, which stood firm and earned him the Iron Cross (IInd Class). The king believed them, unaware that though this part of the Prussian line was falling back, the entire French army was on the run. The only French who stayed put did so out of fear to leave their shelters. Once again, the Leuthen Chorale, whose melody had been composed two centuries before by the house-tutor of the von Blumenthal family, swept over the Prussian army. The victory was needlessly expensive, and the von Blumenthals were lucky all to have survived. But although 20,000 Prussians were lost to 12,000 French, the strategic gains were considerable. The Prussians had now cut the largest French army off from the rest of France. Nothing lay in their way to Paris. Bazaine retired into Metz again, where it took the Prussians a mere six corps to lock him in.