When moving pictures became a popular form of entertainment for the masses it was obvious that, besides using this new media to show many aspects of day to day life and vistas thus far unobtainable to all but a small percentage of the worlds population, it would not take a great leap in the minds of the pioneers of cinematography to push the bounds of this new art form into other aspects of culture.

History has been shaped by military events and therefore it was natural that film makers the world over would eventually attempt to show images of passed glories involving not only military exploits from their own countries past, but go out on a limb and attempt to portray events taken from biblical and historical situations, at times with very scant attention being paid to what actually occurred, but with more emphasise on spectacle and pure entertainment. The Old Testament of the Bible contains so many references to battles that it was small wonder that the moving picture industry latched onto making such films, which have come down to us today as “Sword and Sandal” epics. However, when trying to portray events from passed battles from history that are well recorded and also ingrained into a countries collective popular idea of historical fact then great care should be taken when attempting to sort out truth, myth and propaganda.

David Wark Griffith

David Wark Griffith (1875-1948), a bigot, racist, and not the sort of chap you would like to socialize with was, nevertheless, one of the true innovators of cinema. His production of “Birth of a Nation,” also known as the “Clansman,” was the first moving picture to use the then pioneering technique of outdoor natural landscapes, and the montage effect of cross-cutting between scenes. He started filming Birth in 1914, and although not having had the benefit of military training himself, his father, Jacob Wark Griffith – “Roaring Jake”- who had been a Confederate Lieutenant Colonel in the 1st Kentucky Cavalry during the war between the states and who died when young David was only ten years old, probably gave him a working knowledge of army and battlefield situations. Also it must not be forgotten that the civil war itself had only ended fifty years before Griffith started filming and therefore there were plenty of veterans from both sides from whom he could obtain first hand information on battlefield conditions. He also received assistance from experts at West Point Military Academy, and was also loaned authentic cannons by that establishment for use in the battle scenes, no doubt also having to teach extras the skills of loading and firing blank rounds?

Filming took place around Los Angeles San Fernando Valley, before Hollywood became the centre of the American film industry, and Forest Lawn Hills, once part of the Spanish Rancho Providencia then the Lasky Ranch and now Forest Lawn Cemetery, was used for the reconstruction of the battlefield. Although Griffith had only some 600-700 extras, his skilful use of cutting from long to short views, together with smoke effects strategically placed to partially hide sections of the landscape, make it appear as if thousands are in frame.

Birth of a Nation. Available for free download at the Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/dw_griffith_birth_of_a_nation

His historical accuracy in uniform detail has proven to be far better than some later attempts at portraying how each side looked under campaign and battle situations, Griffith depicting troops in worn and dirty uniforms with the Confederates in particular shown wearing a mixture of military and civilian clothing in keeping with how the armies of the south would have appeared during the Civil War.

Unfortunately we do not know precisely just how Griffith managed to direct and coordinate the battle sequences over such a vast distance. He probably used a tower scaffold to film the elevated views looking over the battlefield, using a megaphone from this perch to convey instructions as the action progressed. However, it takes a lot of control and timing to get even a few hundred extras to act in unison and one suspects that Griffith had certain individuals placed in each grouping on the field who had been instructed to follow per-set guidelines once “Action” had been called? Whatever his failings as a man, he certainly remains one of the first and foremost film makes who could portray mass action on screen.

Abel Gance

The French film director and producer Abel Gance (1888-1981) originally intended to make a six-part life of Napoleon, of which only the first part was ever completed,in 1927, detailing the early life of Napoleon Bonaparte from his days at Brienne military school, through to his commanding the French army in Italy in 1796. The film is full of pioneering techniques including the use of wide-screen scenes using triple cameras to give a panoramic effect. Gance’s use of hand held cameras and a camera mounted on the back of a horse were truly innovative and his filming techniques unique for the time. Unfortunately his attempts to portray battlefield scenes fail to impress. Although he shows the French Army of Italy in its tattered and worn uniforms marching here and there and either milling around or on parade in what looks like a rock quarry, it is obvious that Gance, like Griffith, had only a few hundred extras at his disposal. Unlike Griffith however, Gance does not use the same skills in showing the viewer any great panoramic shots involving troops engaged in battle. When we do have a brief glimpse of action they are disjointed, jumping from shots of Napoleon waving his sword on a hilltop to views of buildings where one or two white uniformed figures (representing the Austrians) are seen flitting in and out of rolling billows of smoke; indeed, Gance seems more concerned to show the audience shots of dirty faced soldiers marching and singing accompanied by the shadow of a soaring eagle thus depicting French solidarity and Napoleonic glory rather than the real nuts and bolts of warfare during this period.

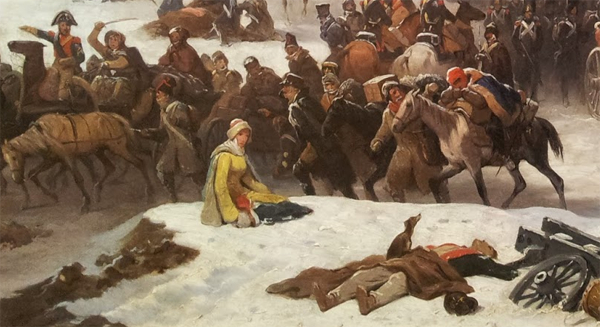

When Gance had another crack at Napoleon in his 1960 film Austerlitz he did have a few more extras in the form of some 2,000 soldiers of Tito’s army, the outdoor battle scenes being filmed in Yugoslavia. Despite having such stars as Orson Wells, Jack Palance and Claudia Cardinale to boost the films appeal, Gance once more seems out of his depth when attempting to portray mass action sequences. What we get are the various stages of the battle being related to us from the perspective of characters on both sides in terms of, “Look, there at Tellnitz, Davout is holding on,” and “There, on the Pratzen Heights, Soult is driving the enemy off.” All of this being delivered with sweeping gestures on a landscaped sound stage in the film studio, with quick shots taken on the outdoor set showing troop formations moving over a terrain with a few burning buildings here and there, which look like what they in fact are, wood and cardboard mock-up’s.

One can see by the troop spacing above that Gance was trying to fill the screen with his limited number of extras in order to give a better mass effect. The burning house looks like something one sees today at a battlefield re-enactment; however, he did try to show the Russian and Austrian army in their correct uniforms, even if much of it was guess work. The indoor sound stage battlefield reconstructions show that Gance paid attention to French Napoleonic uniforms and of course he was greatly assisted in this by having access to the military museums in France, as well as the works of such famous military artists as Detaille and Meissonier, who specialized in battle paintings depicting events from the First Empire.

It is clear that Gance did not have the resources at his disposal to make Austerlitz an epic film. Also, although he was certainly one of the great innovators of moving pictures, he was not in the same league as Griffith when it came to showing mass action scenes and detailed close up fighting sequences.

Sergei Eisenstein.

When considering the use of propaganda in films, and especially in battlefield scenes, then a brief look at the work of some directors is worth while to show to what lengths a state would go in order to boost the morale of its people by manipulating events from the past that were becoming pertinent to the here and now.

Sergei Eisenstein (1889-1948) made his first sound film, Alexander Nevsky, in 1938. Although he had an assistant director and a co-scenarist to help him, these were mainly on set to see that Eisenstein kept to Stalinist dictates by sticking to a strict timetable and not adopting formalism.

In the film monks of the order of the Teutonic Knights have invaded Russia in the 13th century and slaughtered the population of the city of Pskov. Alexander Nevsky gathers an army at Novgorod and defeats the Germans on the frozen Lake Peipus. The scenes of the build up to the battle on the ice and the battle itself show clearly the political tension between Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany when the film was being made, and the allegorical use of swastikas on various objects carried by the Teutonic army, together with some of their troops being shown wearing Stahlhelm style German storm-trooper helmets, are clear references to the threat posed by Hitlers Nazi’s.

![]() Although the battle sequence was shot just outside Moscow during a hot summer the cinematographer Edward Tisse managed to make the countryside look as if it is winter. He created artificial snowfields made from tons of sand, painted the trees with an ice blue water paint then dusted them with powdered chalk, and the ice was made from a mixture of thin melted glass and tarmac, propped up on huge collapesable supports that could be slowly lowered to make the ice appear to be breaking up.

Although the battle sequence was shot just outside Moscow during a hot summer the cinematographer Edward Tisse managed to make the countryside look as if it is winter. He created artificial snowfields made from tons of sand, painted the trees with an ice blue water paint then dusted them with powdered chalk, and the ice was made from a mixture of thin melted glass and tarmac, propped up on huge collapesable supports that could be slowly lowered to make the ice appear to be breaking up.

Using no more than a thousand or so extras, Eisenstein manages to give the impression of tens of thousands. This could be done by showing the Teutonic army first approaching from one direction clad in their flowing white robes bearing the cross, their heads covered by bucket helmets, then, once again using the same extras, as Nevsky’s army, approaching from the other side dressed in conventional armour. The positioning of all the extras in two or three lines filling the whole screen, with the camera angle at eye level, giving the effect of a large army. In fact, as can be seen below, the mass of lances are concentrated in the centre of the frame, thinning out on each side where the extras are fewer. Likewise with Nevsky’s army, once again filling the screen in a distance shot and looking like a dense force advancing. However, a quick count of the spears show that only a few lines of men have been used, a large army would show a forest of spear staves denoting its depth. We will see later how this technique has been use in many other films up to the present day.

The mass gathering above possibly shows almost the whole of the extras that were used in the battle sequence, here dressed as Nevsky’s army.

Veit Harlan

Being a sound film Alexander Nevsky has become the definitive motion picture in the use of stirring musical narrative, the score of Sergei Prokofiev becoming the touch stone for modern compositions that accompany epic movies.

In Nazi Germany, as in Stalinist Russia, the film industry was strictly controlled by the state. Like Stalin, Hitler and his henchmen were keen to show the German people and the world their own versions of history glorifying great deeds from the countries past.

In Nazi Germany, as in Stalinist Russia, the film industry was strictly controlled by the state. Like Stalin, Hitler and his henchmen were keen to show the German people and the world their own versions of history glorifying great deeds from the countries past.

The director/producer, Veit Harlen (1899-1964) had already directed films showing Prussian-German rise to power, and in particular the campaigns of Frederick the Great, a favourite subject dear to the heart of the Fuehrer. In Der Grosse König (The Great King), made in 1941 and at the height of Germany’s success in the war, Harlen juxtaposes the exploits of Frederick with those of Hitler, promoting the idea of German unity, strength and military greatness. Four years later in the film Kolberg (1945), with the Allied forces knocking on the gates of Berlin,we get another rousing tale of the German people fighting on against the invading French under Napoleon in 1806.

The hypocrisy of the Nazi regime was never more evident than in the production of this film. The story was taken, in part, from a book written by the Nobel laureate Paul Heyse who, being a Jew, was not given a credit in the film. This was typical of the mealy-mouthed yes man of Nazi propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, who was desperately trying to boost what was left of Germany’s faith in a lost cause.

Much has been written concerning the production of Kolberg, most of it, like the film itself, based on unproven facts. The actual siege took place in 1806, the year of disaster for Prussia and her much vaunted army. We are shown happy citizens enjoying an almost idealistic way of life, happy and carefree until threatened by the advancing French army, which causes the populace to unite under a leader named Nettelbeck who prepares the town for a siege. Finally realizing that only a strong military leader can help save the town General August Neidhardt von Gneisenau arrives, confronting Nettelbeck and eventually persuading him that only one determined and strong man can save the town from disaster (shades of the Fuehrer). The town is unhistorically saved and we are than moved forward in time to 1813 when Napoleon was fighting a campaign in Germany against the combined armies of Russia, Austria, Sweden and Prussia, the latter having quit its alliance with the French Emperor and proclaimed a war of liberation.

The battle sequences have been variously described as containing anything from 50,000 to 180,000 extras, all of which is pure nonsense. No more than 5,000 or 6,000 second line soldiers were used, plus hundreds of citizens of Kolberg. The uniforms, at least in the massed battlefield scenes, look quite realistic, and the grouping of the French as they are seen advancing, is not too far from how these troops would have been on the field in 1806.

Although, en-mass, there seem to be tens of thousands advancing in the above stills from the film, what Harlan has done is to reduce the unit size to obtain this effect. Where a French or Prussian infantry battalion would normally be between 500 to 1,000 strong, a head count above shows that each group contains only about 50 men each. By stretching two or three dozen of such groups across the landscape, which would require no more than at most 3000 extras, the impression of a large army is obtained.

The irony of Kolberg is that during the Second World War, and soon after the film was completed, the town itself was once more under siege by the advancing Red Army. It fell to the Russians in March 1945 and many of its citizens were deported. Kolberg is now part of modern Poland and as been renamed Kolobrzeg.

Sergei Vasilyev

The old phrase, “There’s trouble in the Balkan’s” was no exaggeration well before the outbreak of the First World War. The tottering Ottoman Turks had been desperately trying to keep together their crumbling and heterogeneous hold on the Balkan Peninsular for over a hundred years. In 1876 Russia intervened to aid their Bulgarian brothers against the oppressive regime of the hated Turks- a great and heroic struggle for a Russian film director to get his teeth into.

Sergei Vasilyev (1900-1959) was, like Griffith, a director who could handle battlefield sequences with skill and ease. The film, Heroes of Shipka (1955), dealing with the war of 1876, was probably one of the best action movies of the 1950’s. The mass movement over vast areas of several thousand extras, the attention paid to equipment and uniforms, and the use of actual firearms used during the war of 1876, together with beautiful colour photography, mark this film out as an outstanding example of how to construct battle scenes. Although its whole theme is to show Russia as the saviour of the oppressed and downtrodden masses, Vasilyev nevertheless used a softer approach and far better handling of events than Haldern attempted in Kolberg.

The river crossing shots taken from an elevated position high above the action compare with anything digital computer cobbeling together can do today. The director and the crew are actually there and the scenes below are real; the action a visual treat.

Vasilyev had already shown his ability to handle mass action scenes in his 1934 film Chapaev and deservedly won best director at the Cannes Film Festival in 1955 for Heroes of Shipka.

King Vidor

In 1956 the motion picture director King Vidor (1894-1982) attempted to adapt Leo Tolstoy’s sprawling novel, War and Peace, onto the big screen. Considering his passed record with such films as The Big Parade, Stella Dalla and Duel in the Sun, then Vidor was considered a director who could possibly just make the transition from epic novel to epic film. Unfortunately trying to squeeze a storyline involving dozens of quite complex characters and their changing attitudes over a period of eight years onto a film of just over three hours duration proved a failure, even though, in my humble opinion, Vidor did make a half-way good effort in his depiction of the battle of Borodino.

Filmed in Vista-Vision, War and Peace was shown in the UK sometime in 1956/1957, and as a young boy of 11 years of age with a great interest in military history, I was taken along by my parents to see the film. The trailer for War and Peace, shown the week before the film was screened at our local cinema, stated that it contained 10,000 extras, and indeed, when viewing the Borodino battle scenes, it certainly does appear to have been no exaggeration. We see one of the principle characters, Pierre Bezukov (played by Henry Fonder), walking up the slope of a tree covered lane while being passed by Russian artillery limbers and cavalry, finally emerging onto a hilltop from where he has a panoramic view of the battlefield laid out in front of him. He slowly walks while watching the action, the camera positioned so that we follow Pierre’s perspective, taking in the full spectacle unfolding before him. We see distant troop formations drawn up in columns and lines wearing a mixture of blue and white uniforms. Puffs of smoke are rising from artillery fire and explosions are erupting across the landscape, which itself covers several miles. In the foreground of the action more lines and columns of infantry and cavalry are in the process of closing on each other< with still more smoke billowing up into a clear blue sky, all rather good stuff.

The scene above is supposed to depict the Great Redoubt, or Raevsky Redoubt at Borodino, which was a major strategic point on the original battlefield. However, whether for more cinematic effect or just because no member on the films military advisory staff knew anything about the actual battlefield terrain (not surprising not being able to visit the site with the cold war at its height), then Vidor’s representation gives the impression of being situated on a miniature alpine slope, whereas,in fact, the original construction was excavated by hundreds of serfs just prior to the battle on a low knoll with a very deep ditch in front. Vidor’s redoubt holds a six gun battery, the actual redoubt held eighteen twelve-pounder cannon and covered an area three times greater than depicted in the film.

The assault by the French on the redoubt starts off reasonably well, with a large formation of infantry seen approaching in several lines up the slope, but not accompanied by any mounted officers and with tricolours placed haphazardly here and there in the ranks. The actual mode of attack for the French was in column or in mixed order, column and line, and normally preceded by a swarm of skirmishers who fell back into the ranks as they closed with the enemy. For a better visual effect Vidor shows the Russian gunners holding their fire, whereas in a real battle they would be pounding the enemy with round shot until, when they came within about 100 meteres, flaying them with cannister like a huge shotgun.

The Russian artillerymen are well represented in their green uniforms and shako’s, even if the shade of green is slightly different from the actual colour of the originals. The troops supporting the redout are, like the Russians in Gance’s film, shown as Pavlovski Grenadiers, but Vidor’s have slightly better uniform detail and he almost got the Russian standards right!

The French infantry in this shot look like Imperial Guard but, in fact, Napoleon never used his massive Guard reserve during the battle.

When the infantry attack is beaten off we see napoleon (played by Herbert Lom) giving orders for a cavalry assault, what we than get is a charge resembling something more like a fox hunt rather than a disciplined advance by well trained mounted troops. The uniforms are only accurate as far as being blue and the helmets are a cross between classic style dragoon (with false leopardskin turban) and cuirassier, but many without the true horsetail hair of the original. Cloaks are worn to cover many defects in dress such as having to show the rear view of a cuirass or cartridge pouch, and once again too many tricolour flags are dotted about for effect. In the final scene, when the cavalry enter the redoubt, a few Lancers of Berg type mounted troops are shown for good measure wearing the Polish czapka headgear.

A good representation of troops drawn up in reserve but not enough movement or smoke.

Towards the end of the film we have a spectacular re-staging of the remnants of Napoleon’s army crossing the Berezina River as it retreats from Moscow, something that Tolstoydoes not mention in his novel. Allowing for the river in Vidor’s reconstruction being far too wide, his actual portrayal of the crossing is quite well executed and show that either he or his military advises had studied the painting by Suchodolski and the lithograph by V.Adam.

Unfortunately what we get from Vidor’s epic in the end is one or two passable scenes of military action which have been inserted into what is really no more than an elaborate Hollywood love story.

Sergei Bondarchuck.

Having taken a look at what Vidor attempted to do Hollywood style it is now worth assessing what the Russian film industry came up with when they took on Tolstoy’s epic.

The Mosfilm Company is the oldest motion picture establishment in Russia, therefore it was natural that they should be the ones to produce this gigantic undertaking, together with backing from the Soviet government. After much time spent in deciding upon a suitable director, they finally settled on Sergei Bondarchuck, who also plays one of the main characters in the film, Pierre Bezukov. The film was made between 1961 and 1967 and cost an estimated $10,000,000 (8,300,000 rubels) which, had it been made in the west, translated to a staggering $90,000,000.

The main battlefield scenes are in part one and three of the re-structured versions on DVD/Video from 2012. In part one of the film another of the main characters, Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, has joined the Russian army and is serving as aide-de-camp to General Mikhail Kutuzov. Andrei askes to be allowed to serve with General Prince Bagration who commands the Russian rearguard but is refused by Kutuzov who states that he needs him on his staff. However, we then find Bolkonsky with Bagration anyway, as that general attempts to hold up the French advance at Schöngraben with, according to the subtitles in the English version, 40,000 men, when in fact Bagration had in reality no more than 7,000-8,000 troops on the field in 1805. The action at Schöngraben was filmed in the Carpathian Military District of the Soviet Union and 3,000 troops of the Soviet army were used in the battle sequence.

Bondarchuck’s military advisers, General of Army V.Kurasov, General of Army M.Popov, and Lieutenant-General N.Oslikovsky did a good job in reproducing the marching cadence of both the French and Russian troops during the Napoleonic Wars, and the uniforms, at least for the Russians, are almost exact for the period, changes occurring in military dress over the next few years. The French uniforms themselves are quite well reproduced, with the exception of the shako, which all seem to either have red banding or be totally red and all have red plumes; whereas, in fact, black was the predominant colour for all infantry, only the elite companies of grenadiers having a red plume.

By subtle use of camera angles and terrain Bondarchuck makes his few thousand extras look more like tens of thousands as he, like Griffith, shows long shots over the battlefield with troops moving through billowing smoke effects and explosions. The Russian artillery battery scenes is particularly well executed, with sweating cannoneers handling dirty smoking guns, while dense black smoke drifts across the screen.

Austerliz.

The Austerlitz battle scenes, (filmed near Svaliva) at least in the first stages, are well organised, opening with the Russian troops who have been bivouacking in some vineyards during the night before the battle now stirring as the famous “Sun of Austerliz” starts to pierce through the dense fog. We now cut to a shot of Napoleon riding among his troops, who are holding torches aloft to guide their Emperors route; a situation that actually occurred on the night before the battle, but sometime earlier than shown in the film. We then return to the Russians who are now forming up and moving forward.

As the mist thins out we once again see Napoleon on horseback peering through his telescope towards the enemy position, the smoke from camp fires and the mist shredding out to reveal the Russian columns in the valley being just discernable. Like Vidor, Bondarchuck does not seem to have any real knowledge of the actual terrain on which the battle was fought in 1805, the Pratzen Plateau in the film being overshadowed by the Carpathian Mountains in the background. The actual Pratzen high ground is really no more than an elongated hill-top with no higher ground overlooking it. The Russian columns seen advancing are apparently moving to turn the French right flank, as happened in the real battle but Napoleon himself would not have been able to see this occuring due to the fact that he was actually, at this time, some four miles futher north at the Zuran Hill. He would have been able to see that heavy columns of enemy troops were moving on the Pratzen, but they certainly would not be coming directly towards him as shown. There is now a fade-out and then the scene opens once again now showing French troops advancing; supposedly these are meant to be Marshal Soult’s IV Corps moving to attack the Pratzen heights?

Next we go back to Prince Andrei Bolkonsky galloping up to General Kutuzov, who sits his horse on a hill top with troops spread out behind him. The mist has now cleared and the sun is shining; a quick cut back to Napoleon and then back to Kutuzov who realises that the Russian Tsar, Alexander I, together with his military entourage are approaching. The exchange that now takes place between Tsar Alexander and Kutuzov, if actually took place, is true to Tolstoy’s novel. Alexander asks Kutuzov why he is still waiting and not advancing, to which the general replies that all the units are not yet formed up. Alexander than, sarcastically, remarks that they are not at a ceremonial parade where the march-past cannot begin before all the troops are in good order, to which Kutuzov replies seriously that he is waiting because this is not a parade but a battle, intimating that one event is trivial while the other is of greater importance. Finally bowing to his Emperors wishes Kutuzov orders the advance.

Back to Napoleon once again. Now he is seen on horseback with his staff off to the right and the Imperial Guard drawn up in close order behind. The sky is clear and Napoleon takes off one of his gloves,swiping it down sharply as the signal for the advance, which according to earlier scenes they had already commenced? French and Russian cavalry are seen charging each other ( some of these shots are also used in the Borodino sequence) with riderless horses shown milling about in great numbers. Here things get totally confused as we see cavalry dashing around rather aimlessly and infantry advancing then falling back without the viewer having any idea of what is taking place. Andrei attempts to rally a handful of troops but is wounded carrying a standard, he falls, end of battle.

The actual cavalry action between the French and Russian Imperial Guards would have been worth dealing with in some detail as it would have at least given the audience an on screen spectacle, provided some form of narrative in the script had been used to inform them of what was taking place. All we get from Bondarchuck is French carabiniers (wearing uniforms and helmets of a later period) and Russian cuirassiers charging about all over the place without any real purpose.

Borodino

The muddled battle sequences continue in the films re-enactment depicting Borodino in 1812, although it must be admitted that the build up to this event follows Tolstoy’s account closely.

Pierre Bezukhov (played by Bondarchuk) is seen wearing a white top hat and clean civilian clothes as he walks among throngs of Russian wounded and retreating troops returning from their battle with the French for the Shevadino Redoubt, which was a forward earthwork built by the Russians to blunt the enemy advance on their main position. Uniforms have changed slightly since 1805 with the bell-topped shako now being worn by the Russian infantry, while the hussars we see moving through the infantry ranks wear the exaggerated elongated plume.

Pierre asks an intendant officer about the Russian position and is told to go through Taratinovo village and take a view from the mound there. From this we have to assume, having no prior knowledge of the outlay of the battlefield, that Pierre is at that particular moment somewhere well behind the Russian front line. Walking on he then comes upon hundreds of serfs dressed in white smocks toiling to construct a field fortification. Climbing a mound he asks some officers who are studying the French position through their telescopes where both armies are deployed. Suddenly we are shown a huge column of troops following the icon of the “Black Virgin of Smolensk,” which is being carried around the battlefield to boost troop morale with religious fervour. Slow camera panning gradually lifts the viewer from ground level up above the gathering masses who stretch way back into the distance giving us a sample of just how many extras (Soviet Army) Bondarchuk had at his disposal for this particular part of the film. The souvenir book detailing the making of the film that was sold at the Curzon cinema in London when the film was shown there in 1968 gives the figure of 120,000 extras (see Appendix). In fact Bondarchuck himself stated that he used no more than between 12,000-14,000 soldiers of the Red Army, including a complete brigade of cavalry. Someone obviously added a nought for greater publicity effect as in Harlan’s Kolberg.

Back with the film and we are now at a bivouac during the evening before the great battle. Pierre and Andrei are discussing what the morning will bring and Andrei, after a diatribe on the effects of war, orders his friend to leave, the screen now fades out, opening again briefly to show Napoleon walking outside his headquarters tent looking across the darkening fields towards the Russian camp fires – fade out.

The screen now erupts with explosions and movement, and the viewer is once again on the same section of the battlefield where the religious procession took place the day before; now smoke from artillery batteries drifts across the scene while peasants (or militia/opolchenie) are shown in the foreground removing the wounded from what appears to be the Bagration Fléches, three arrow shaped fieldworks on a slight rise of ground left-centre on the Russian side of the battlefield. Once again the viewer is left in the dark concerning locations on the reconstructed battlefield owing to a lack of some form of narrative or dialogue to explain what is taking place. The meandering watercourse seen in the background is probably meant to represent the Kalocha River, but once again without prior knowledge of the topography of the battlefield the audience remains none the wiser.

Pierre is now seen at Kutuzov’s headquarters near the village of Gorki, on the Russian centre right, some two miles from Borodino. We then cut to Napoleon pacing up and down aimlessly in front of his reserves with his staff grouped close by and troop movement and deployment taking place around him amid billowing smoke and dust. Compare this with Vidor’s stactic placing of Napoleon where no smoke or noise of battle can be detected. The occasional flash of a bayonet catching the sunlight adds another detail to Bondarchuck’s recreation of the battle although one suspects that in order to obtain this effect small mirrors may have been attached to the end of the muskets thus ensuring catching the suns rays? We see the French infantry advancing in mass formation, the director having the Red Army extras trained to march in the French and Russian cadence of 1812- 120 steps per minute for the French, 75 steps per minute for the Russians- in order to make it authentic. This is one of those little touches which make one wonder why Bondarchuck bothered with such detail (when possibly none of the audience took any notice) but left out any explanatory narrative describing what was taking place?

Above, showing the immense scale of the action sequences which involved walkie-talkie communications to get the various units to move on cue. Note red ring denoting a modern Russian army rifle with bolt action. Bondarchuck only had a limited amount of actual muskets.

In one scene the marching columns of French infantry are seen passing a white structure which, although it may have been recognized by many of the films Russian audiences having knowledge of the battle and the history of the patriotic war of 1812, nevertheless remains oblivious to all but a few outside the Soviet Union. It is meant to represent the Byzantine church in the village of Borodino, but by just being plonked down on the terrain while troops march passed it gives no impression of its significance or it actual whereabouts on the battlefield. This is strange because the battle itself is known today as Borodino (although the French call it the Moskva after the main waterway that flows to the north west of the battlefield), and was held by the Russians at the commencement of the battle; we even see Pierre briefly on the outskirts of the village watching as French artillery rounds explode among the defending troops and houses, however we are soon whisked swiftly away past close up shots of wattle fences, lines of soldiers and clusters of silver birch trees, until we find that Pierre has finally fetched up inside the Raevsky Redoubt. Here, like in the scenes depicting Russian artillery at Schöngraben in part one of the film, Bondarchuk’s handling of the action is very well directed; probably being one of the great battlefield set pieces in film history and coming as close as we possibly ever will get to an actual representation of how things looked during a Napoleonic battle, and all without the use of a computer.

We see the redoubt being entered by white uniformed infantry wearing bearskin bonnets which, to the layman would mean absolutely nothing, not knowing if they are meant to represent friend or foe; in fact they are supposed to show that Napoleon’s invading army was made up not only of French troops but also contingents from states allied to them. Here the troops shown are probably being portrayed as Westphalian Guard Grenadiers (Napoleon’s younger brother, Jerome, was King of Westphalia). These troops were part of General Junot’s VII Army Corps.

Unfortunately at around this time in the battle sequence Bondarchuck gets carried away and becomes too impressionistic rather than giving the viewer a steady flow of events as they occurred during the actual battle. We see Prince Bagration hatless advancing with the Russian infantry while being bypassed by French cavalry charging in the opposite direction, once again the ubiquitous carabiniers shown in part one. These troops are dashing right passed Bagration’s infantry that in an actual battle situation would be a prime target for cavalry – infantry in column – an open invitation for disaster as the normal procedure when enemy mounted formations were close by was for infantry to form square, the only real way of avoiding being hit in front flank and rear without disaster.

Cut to Bagration now sitting somewhere, still hatless, looking on at the engagement and praising the French for their courage with “Bravo!, Bravo!” although we cannot understand just what he is bravoing? Cut again to Russian cavalry and cossacks crossing the river, possibly the Kolotcha (?); these are probably meant to be Uvarov’s cavalry flank attack at around 11 a.m. against the French right wing, but once again this is speculation. The cutting and editing in this way, just showing explosions and soldiers marching to and fro with no real explanation or continuity of what is happening ruins the whole effect of what could have been a chance to show this major engagement of military history in educational detail. As the military historian, Dr Christopher Duffy stated about the film in his work, Borodino, Napoleon against Russia 1812, ‘Without the support of an intelligible narrative, the effect of mere spectacle is subject to the law of rapidly diminishing returns.’

Waterloo 1970.

Bondarchuk obviously learnt a great deal from his experience in directing War and Peace as he did a far better job, although not without some howlers, when he tackled the military scenes in the 1970 film Waterloo.

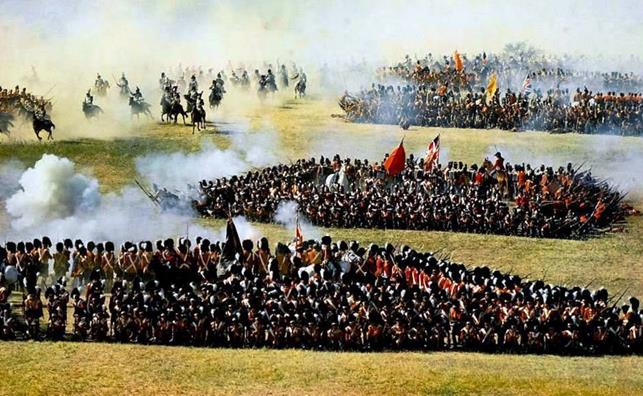

It was quite ironic that the producer of Waterloo should be the same one who produced Vidor’s version, the Italian, Dino De Laurenths, who himself had been toying with the idea of making a film about the battle of Waterloo for many years but had been put off by the enormous cost of producig such a film in the west. Now, having the backing of the Russian Mosfilm organisation, who contributed over $6,000,000 towards the cost and 16,000 soldiers of the Red Army as extras, he was able to take on this mammoth undertaking.

It must be said that, even for allowing for the critical put downs when the film was released, Rod Steiger’s portrayal as the overweight and at times manic Emperor Napoleon, is just about as perfect for “The Great Thief of Europe” at this stage in his life as it gets. Looking at some of the more down to earth images of him and readung about his declining military prowess during the years 1812-1815 one sees a slow deterioration of his heath and physical appearance, together with a growing tendency towards towards being short tempered and lethargic, all of which Steiger dishes out with relish. Christopher Plummer also does a good job as the pompous aristocrat Arthur Wesley (later Wellesley), Duke of Wellington.

The action scenes in the film attempt to follow the actual events of the battle as they occurred during its course, however, there are some errors which, although not detectable to the non military minded viewer, nevertheless are glaringly obvious to those who have studied the battle in detail. First the viewer is taken through the build up prior to the main event by showing the French army crossing a river (actually supposed to be the River Sambre) and entering Belgium territory while Wellington attends the Duchess of Richmond’s ball in Brussels. We only find out that the Prussian army under Field Marshal Blücher von Wahlstadt, allied with the British, are also somewhere in the region when their liason officer, General Baron Müffling, arrives at the ball and informs Wellington that Napoleon has crossed the boarder and placed himself between both of their armies at the town of Charleroi. Thereafter we are not shown or informed of any details regarding the battle that took between the Anglo-Dutch Army and almost half of the French army under Mashal Ney, at Quatre Bras, on the same day (June 16th) that Napoleon defeated the Prussians at the battle of Ligny. Even this engagement is only dealt with almost in passing with glimpses of Blücher stating that although being defeated he will still keep his word and attempt to aid Wellington after he has regrouped at Wave. On the French side we see Napoleon ordering Marshal Grouchy to pursue the defeated Prussians. The French Emperor is seen amid the wreckage of the Ligny battlefield, some sources stating that Bondarchuck originally filmed part of this battle but cut it out later. This did not occur because the costume wardrobe department had only a few Prussian uniforms and most of these were the wrong colour, being made from black material which, even in the film is mentioned by Wellington (Plummer) as being “Prussian Black.” The Prussian troops wore mainly blue (Prussian Blue) uniforms, only a few regiments in their army wore black like the “Totenkopf Hussars.” The Brunswick contingent serving under Wellington wore black.

After scenes showing Napoleon in his headquarters at La Caillou (although the viewer is not informed of its name) where he spent the night of June 17th-18th, we are shown heavy rain falling and cut back and forth from Napoleon to Wellington as both commanders consider the others options. Then the Emperor orders his staff to leave him and retires to his camp bed obviously suffering from the stomach complaint that plagued him in later life. The night slowly gives way to day as the camera slowly pans around Napoleons room and comes to rest on a window overlooking the area outside where troops are starting to stir themselves from the rain soaked ground and we see the sun begin to pierce through the mist.

Filmed outside Uzhgorod in the Ukraine the terrain was made to look as close as possible to the actual battlefield of Waterloo and a reasonably good reconstruction was made, with the exception of some shots showing rather too much high ground in the background, the countryside in this part of Belgium being rolling and fairly flat.

To make the battlefield look authentic a team of labourers and engineers bulldozed and levelled two hills, deepened a valley, and laid five miles of roads. The farms of Hougoumont, La Haye Saint and La Belle Alliance were constructed and look very close to how the actual building on the battlefield still look today. All this, together with several thousands of trees being planted, plus fields of barley and rye and wild flowers, all added to the atmosphere and realistic appearance of this vast mock-up outdoor film set.

There are some great shots of both armies in their preparatory battle positions before the commencement of the action but, and this is quite strange allowing for the fact that Bondarcuck had so many extras, in some shots where we see the French formations, there are definitely quite a few painted wooden figures mounted in long lines shown placed among real soldiers, their brighter colours and identical height and form making them, once noticed, stick out like a sore thumb. Also some of the British infantry are shown standing around their bivouac areas smoking cigarettes, (not the South American maize wrapped variety) which were not in vogue until after the 1840’s, and then only in limited supply in Europe.

There are some great shots of both armies in their preparatory battle positions before the commencement of the action but, and this is quite strange allowing for the fact that Bondarcuck had so many extras, in some shots where we see the French formations, there are definitely quite a few painted wooden figures mounted in long lines shown placed among real soldiers, their brighter colours and identical height and form making them, once noticed, stick out like a sore thumb. Also some of the British infantry are shown standing around their bivouac areas smoking cigarettes, (not the South American maize wrapped variety) which were not in vogue until after the 1840’s, and then only in limited supply in Europe.

The battle begins with the French attacking Hougoumont, which was intended to draw Wellington into committing his reserves to bolster his right but which, throughout the whole battle, remained, albeit touch and go, in allied hands. Here we can see that, although much care had been taken to show the woods covering the approach to the château from the French position, the trees are only silver birch, and young saplings at that, whereas the actual wood was made up of mixed deciduous trees of a greater age than the ones shown. Times are shown on screen during the early stages of the battle so that the audience is aware of when things were taking place, certainly better than the Borodino action scenes where the viewer is given no idea of either the location or the time of each sequence.

The only troops of Wellington’s army we see throughout the battle are British contingents, which made up about one third of the 68,000 or so troops of all arms at Waterloo. The allied units consisted of Dutch- Belgian; Brunswickers; Nassau; Hanoverian and KGL (Kings German Legion), but we never see any of these on screen, just a passing mention of Bylandt’s Brigade (Dutch-Belgian) being broken. This does not detract from the action however. To have used too many different uniforms to show the various allied units on the field would have caused some confusion to the viewer who probably would be unaware anyway of what they were supposed to represent?

The next stage of the battle shows a massive attack by French infantry, which fails and is driven back by British troops under Sir Thomas Picton, who is killed leading his men forward, a fact that did occur during this stage of the battle. Then we see the Scots Grey’s cavalry regiment following up the French as they fall back. This, for its time, was very difficult piece to direct, showing considerable skill in timing and slow-motion action. After all, to get about 200 or so mounted men and their horses to perform on command amid smoke and explosions takes great care on the part of all involved in getting it to look right. The only downside was that the Russians still used the “Flying W” to make the horse and rider crash to the ground. This entailed attaching hidden wires to the rear legs of the horse so that when the wire played out to its full length the horse would fall. This technique had been band in the west after many of the horses used in such stunts became crippled and had to be destroyed. With the arrival of French lancers the Scots Grey’s are forced to retire and we are shown the death of their commander General Ponsonby who has become mired down in the mud killed. Earlier in the film Ponsonby relates that his father had been killed by French lances, which he was not. Ponsonby’s father was a politican and died in bed; the character in the film is predicting his own death.

The next stage of the battle shows a massive attack by French infantry, which fails and is driven back by British troops under Sir Thomas Picton, who is killed leading his men forward, a fact that did occur during this stage of the battle. Then we see the Scots Grey’s cavalry regiment following up the French as they fall back. This, for its time, was very difficult piece to direct, showing considerable skill in timing and slow-motion action. After all, to get about 200 or so mounted men and their horses to perform on command amid smoke and explosions takes great care on the part of all involved in getting it to look right. The only downside was that the Russians still used the “Flying W” to make the horse and rider crash to the ground. This entailed attaching hidden wires to the rear legs of the horse so that when the wire played out to its full length the horse would fall. This technique had been band in the west after many of the horses used in such stunts became crippled and had to be destroyed. With the arrival of French lancers the Scots Grey’s are forced to retire and we are shown the death of their commander General Ponsonby who has become mired down in the mud killed. Earlier in the film Ponsonby relates that his father had been killed by French lances, which he was not. Ponsonby’s father was a politican and died in bed; the character in the film is predicting his own death.

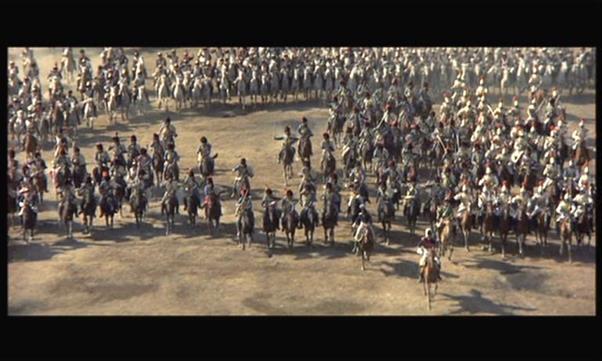

The French massed cavalry attack is another great piece of filming for its time. Here a complete brigade of Soviet cavalry (around 1,500-2,000 men and horse) were used to reproduce what, during the actual battle in 1815, involved eventually over 10,000 mounted troops. One cannot imagine, even with the best computer programs, how one would portray, with any accuracy, this on screen today. The Lord of the Rings fantasy battles show huge compact masses moving in ordered blocks without much attention to detail which, of course, is just how the viewer expects them to look, especially after reading the book. What Bondarchuck’s director of photography, Armando Nannuzzi, had to give was a reasonably accurate impression of the great cavalry attack at Waterloo with limited numbers, which was still a mind blowing undertaking when we consider the organising entailed in getting a couple of thousand mounted extras to perform the task of charging around formations of troops in squares while blank gunfire and explosions are taking place.

The final part of the film showing the Old Guard attacking in a desperate attempt to break Wellington’s line is so-so. Obviously to try and and reconstruct the whole battle stage by stage would become tedious to all but the most stalwart of anoraks. However, a few scenes showing the fighting around the village of Plancenoit (on the French right flank) would have added to the overall effect of the Prussians arriving on the battlefield and Napoleon’s final defeat; once again this was not included because, like the absence of any action at Ligny, no replica Prussian uniforms were available in large numbers.

For all the bad criticism that this film has received over the past fifty years it still remains a marvellous example of how the old directors and their teams could manage such a vast project without the aid of computers.

Stanley Kubrick

There is little doubt that Stanley Kubrick is way up there among the world’s great film directors. Having said that he never really got his teeth into a mass action film other then Spartacus, which he disowned shortly after its release in 1960. In the battle sequence the cinematography work of Russell Mitty (who won an Oscar), although overshadowed by the Kubrick image, should not be forgotten. Before this Kubrick’s only stab at historic battles situations was in the film Paths of Glory (1957), and even here he only shows French infantry going over the top during the First World War, leaving their trenches and being wiped out amid good special effect explosions and terrain, plus some fine camera angles. The atmospheric and beautifully shot 1975 film Barry Lindon, filmed in Ireland with only a limited number of extras for the action scenes, is sadly lacking in showing anything like a real eighteenth century battlefield. Kubrick just plonks a few uniformed Prussian and Austrian troops confronting each other, widely dispersed across a rural landscape dotted about with trees and with hardly any signs of smoke,explosions, cavalry formations or artillery batteries. In another scene showing British Redcoats advancing in rather good reproduction period uniforms and carrying realistic muskets, he stills fails to portray any real sense of a battlefield situation during the period. Viet Harlen’s 1930’s reconstructions of a Frederick the Great battle being far more realistic. With this being said let us look at what Kubrick did with the battle scenes in Spartacus.

Most sources give the figure of 8,000 for the extras used to represent the Roman army under Crassus. The battlefield scenes were filmed in Spain (Kubrick wanted to film in Italy where, for some reason or other, he thought the cost of hiring extras would be cheaper) and the Spanish army supplied the necessary manpower. The overall total for extras engaged in the film is given as 10,000, but this number included many women and children who bulked-out Spartacus’s army. I have no problem with these numbers, however, there does seem to be something not quite right when viewing the advance of the two Roman legions as they march over a rise of ground towards the slave army. For these scenes Kubrick positioned himself on a tower some half mile back from the actual site being filmed, using 35mm Super 70 Technirama format, which was later expanded up to 70mm, allowing high definition panoramic shots.

The opening scene of the battlefield shows the first cohorts of the leading Roman legion coming over the rise, then we cut to a view of the slave army watching their approach, with Kirk Douglas as Spartacus in attendance. Here I did a rough head count of the Roman formations by photographing and enlarging the shot of the whole legion when in came fully into view; there are twenty “blocks” formed in two close columns of 150 men in each, giving 300 troops per “block”, viz.:-3,000 extras for the first legion (a Roman legion actually numbered around 5,000, plus another 4,000 auxiliaries) and the same number for the second legion as it comes over the crest into view-total: 6,000 extras. All the Spanish army extras were, according to the sources, trained in Roman military drill and formations to make the build up to the battle realistic. The problem is, after the initial advance of the two legions the second formation halts and takes no further part in the remaining movement frames of the battle, and was, in my opinion, shown as a split-screen image of the original shots of them advancing. This would then allow the extras from the second legion to be used as part of Spatracus’s army, thus bulking out their numbers which, when we examine their layout as the Romans are seen approaching, show much more spacing and spreading out than in the sequence where they dash forward en mass to attack their foe. There is also a convenient hedgerow running behind Spartacus’s battle position which may have been helpful in the long shots to deceive the viewer into thinking that it is part of his army? This may seem like “nit-picking” but with such a large amount of extras available one would have thought that more could have been done to show the whole Roman army deploying for battle. When we get the scenes where Pompeii and Lucullus’s forces arrive on the battlefield they are shown running forward rather like the start of the London marathon rather than a disciplined body of Roman soldiers.

Note the hedgerow in background and sparse spacing of the slave army, plus the wrong initials on the Roman standard. They should be SPQR, the tail is missing from the letter Q

Strangely enough Kubrick had been planning to make a film about the life of Napoleon during the latter part of the 1960’s, and he had even written a full screen play to accompany it, plus tentatively putting out tenders for making masses of uniforms out of durable paper! However, with the release of Bondarchuck’s Waterloo in 1970, Kubrick shelved the idea, and so we will never know what sort of battlefield sequences he would have presented us with.

Anthony Mann

I include herewith a brief look at how the American film director Anthony Mann handled mass action battlefield scenes.

Although best remembered for directing westerns such as Winchester 73, The Far Country and The Man from Laramie, Mann was also the first director of Spartacus before Kubrick. After only a week as director Kirk Douglas fired Mann stating that, “He seemed scared of the scope of the picture,” what Mann thought about it has remained a mystery, but it could not have effected the relationship between him and Douglas because they teamed up again when Mann directed the war film The Heroes of Telemark.

Regardless of the reasons behind his dismissal, in 1961 Mann was offered the job of directing the medieval epic El Cid, in which he handled thousands of extras in some well constructed battle scenes. The film was a resounding success, so much so that the films producer, Samuel Bronson, employed Mann to direct his next epic, The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). Unfortunately the film was not well received and it flopped at the box office. Nevertheless it still showed that Mann could handle mass action on screen.

Cy Endfield

Cy Endfield, although not among the most memorable of film directors, did make a remarkably good job at showing mass battle scenes when he directed Zulu in 1964. He and producer/actor Stanley Baker, together with cinematographer Stephen Dade, using only a few hundred extras, managed to create the impression of thousands of warriors attacking the mission station at Rorke’s Drift in 1879 during the Zulu War. The station was defended by 150 men of the 24th Regiment of Foot (2nd Warwickshire). The actual number of Zulu’s engaged at the mission in 1879 was somewhere in the reigion of 4,000. These belonged to the Ulundi Corps and had not seen action at the battle of Isandhlwana, in which an entire column consisting of British and colonial troops were annihilated by 20,000 Zulus just prior to the attack on the mission.

Endfield, like D.W.Griffith, only having a limited number of extras to portray the Zulu impi, managed to make it look as if masses of warriors were employed, at least in the opening scenes of the action. By the use of painted shields mounted on long wooden supports, driven into the ground in several lines, plus having his limited number of extras moving as if into position while others are spread out along the crest of an adjacent hill top, the viewer is given the impression of thousands in the frame. By cutting from shots of lines of warriors arrayed on the hillside to others moving across broken terrain carrying Martini-Henry rifles, Endfield manages to keep up the idea that he had far more than the mere 240 Zulu extras that were in fact employed. It is only when the attack against the mission in shown that one can see how few there really were. However, even here, Endfield manages to cut and edit to such good effect that the viewer is still carried along by the action. Truly, Zulu is one of those films that, allowing for some artistic licence, at least portrays a great deal of what a colonial battlefield situation was like in the latter half of the nineteenth century, while showing the Zulu war machine as a formidable force to be reckoned with.

Zulu may be one of the most memorable of war films in British cinematography history but the follow up, Zulu Dawn, was a flop, although Cy Endfield was not the director on this one, he just wrote the screen play. Made in 1979, on the 100th Anniversary of the Zulu War, the film failed at many levels, but did have some very well directed action scenes showing how various stages of the battle of Isandhlwana may have looked.

When one shuts out the fact that the British infantry are mainly decked out in nylon tunics, and that some of the then historical detail regarding the battle has since been proven incorrect, nevertheless the action scenes, directed by Douglas Hickox, are remarkable in showing panoramic views of the battlefield together with some very good close up shots switching to and fro to the various stages of the engagement. The scenes showing the Zulu army itself when discovered comes very close to giving the viewer (whom it must be remembered may not have had much knowledge of the Zulu War) the impression that there are indeed 20,000 warriors swarming forward and spreading out in a chanting back onrushing tide. In fact, no more than about 4,000 extras were used, but each part of the attack jig-saws very well together in showing the immediacy of each moment as it could well have been for those involved at the time.

Final Remarks

There are many, many more examples of film directors who have managed to cope with mass battle scenes involving a few hundred to several thousands being shown on vast outdoor recreations of battlefields, all without the use of any computers. In closing may I recommend to the reader of this article the book by John Farkis, Not Thinkin’…Just Rememberin’… The Making of John Wayne’s The Alamo (1960). Here one will find a detailed account of the day to day work involved in making an epic war film. Even though the film itself is historically incorrect, and there is too much time given over to talk about republics and freedom, the Duke did a very good job of directing some stirring action moments using several thousand extras. One only has to read this book to see what a monumental task the directors of such films had, as well as the way in which the logistics in dealing with transporting and feeding masses of extras, plus, at times, hundreds if not thousands of horses was achieved. One suspects that with the coming of CGI being able to direct films on this scale without its use has become a forgotten art.

Graham J.Morris May 2020

Appendix.

Copies of some souvenir programs are obtainable by contacting me on this site. To date the Spartacus and Alamo programs are sold out. Others such as Cromwell, Khartoum, War and Peace (Bondarchuck version), The Fall of the Roman Empire and The Charge of the Light Brigade are available in limited numbers.