7th March 1814.

For a virtual tour of the battlefield, starting at the observation tower on the Californian Plateau, see this page.

Introduction-Fields of War.

Yves Gibeau shook his grey head and made an outward sweeping gesture with both arms. ‘All this,’ he said, taking in the whole area of his view, ‘All this now peaceful landscape was changed beyond belief in just a few weeks only a year after I was born in 1916.’ His eyes filled with tears and his hands dropped to his side: ‘what men will do for some strange notions of honour, glory, power and personal gain? The old man wiped his eyes and pulled himself up straight, ‘Waste and stupidity is what made me become a pacifist, and I will remain a pacifist as long as breath remains in my body-curse all wars!’

The landscape which Gibeau was referring to lay in the area surrounding the highway of the Chemin des Dames (Ladies Way), situated in the Department de l’Aisne, northern France, where he lived from 1954 until his death in 1994. Its fields and woods had been unlucky enough to be struck by the lightning bolts of battle twice in just over one hundred years, first in 1814 and again, with devastating effect, in 1917. Giberau loved this quite rural countryside and spent many hours each week cycling or walking its hills and valleys. He was born a bastard, his mother having had a tumble in the hay with a French soldier who soon left her and was probably killed in the bloodbath that was the First World War. She later married another soldier, Sergeant Alexander Gibeau, who gave the boy his name. After receiving an education at a series of military schools and taking many officer training courses, at which he did not do well, being ridiculed and maligned by students and teachers alike for reading too many novels, he finally saw active service at the outbreak of the Second World War, being captured by the Germans in 1940 and sent to a prisoner of war camp in East Prussia where he suffered similar humiliation at the hands of his captors as he had received from his fellow countrymen back in France. After being liberated he spent the rest of his life opposing the imbecility of war and the (then) inhuman conditions of military education and training for war. He began writing and in 1952 published his most famous work, Allons z’enfants (Arise, Children), the title taken from the first line of La Marseillaise, in which he describes the stupidity and futility of disciplinarian dogmatism. At his own request he was buried in the old ruined cemetery of Craonne near the eastern edge of the Chemin des Dames.

The irony in the title of Gibeau’s book will not be lost on the readers of this article.

Another Retreat.

In early November 1813 Napoleon Bonaparte with a force of around 80,000 worn and battle weary men, many of whom were already suffering from the early stages typhus, were staggering back to the Rhine River. The allied victory at the battle of Leipzig (October 16th-19th) cost the allies some 52,000 casualties, the French well over 50,000, but to these must also be added a further 30,000 taken prisoner, as well as another 20,000 killed, wounded or captured during the retreat. In material the French lost over 300 cannon and close to 1,000 wagons. Napoleon also lost control of Germany, and his prestige, already having suffered a severe battering after the disastrous Russian campaign of 1812, now sank to still lower levels. General Philippe de Ségur, one of the Emperor’s aide de camps noted that:

The impression I gained of [Napoleon] was vivid, and so painful that it remains to this day. His second disaster was over. The way that everyone regarded him was no longer the same. Misfortune had struck him like any other man, and had bowed his grandeur, so one felt more on the same level with him. One needed to raise their eyes less far to look at him. Everything around him seemed to have changed, but nothing in Napoleon himself. Struck down twice already, he still held his head high, his voice was clipped and peremptory, his manner regal [1]Ségur, P.P. Du Rhin à Fontainebleau: Mémories du Général Comte de Ségur. Quoted in, Leggiere, Michael V. The Fall of Napoleon. The Allied Invasion of France, 1813 – 1814, page 66

The latter part of Ségur’s statement is typical of how all megalomaniacs behave, never admitting defeat no matter how many corpses they leave behind in their wake.

Unlike his rapid departure from what was left of his army during the retreat from Moscow in December 1812, when he was able to return to Paris and start rebuilding his military strength, Napoleon had to remain with his troops for some days after they had crossed the Rhine in order to ensure that the crossing points of that great river were guarded sufficiently, and that some semblance of order had been restored within the various shrunken units of what remained of his Grande Armeé of 1813.

The coalition forces confronting Napoleon were considerable (Russia, Austria, Prussia, England, Spain, Portugal and Sweden, together with the minor German states who were now throwing off the Napoleonic yoke) but, in the northern theatre of operations, did not have a unified and coordinated command structure under a single strong willed military leader. Therefore they were unable to capitalize on the victory at Leipzig to its full extent by not continuing to pursue the defeated French and cause havoc on the Rhine. Indeed, the problem of a unified command structure was to bedevil the allies throughout the entire 1814 campaign, which was always subject to the political whims, wishes and motives of each nation. Not least among these was the growing fear, shared by Austria and Prussia, that the defeat of Napoleon could lead to Russia flexing her not inconsiderable military muscle in the affairs of Europe. For Austria it was their own sphere of influence in the Balkans that could be threatened, whereas for Prussia a fear for their own tentative hold on her possessions in Poland caused much concern. All of this, as one would expect, was also now being considered within the increasingly limited options open to the French emperor.

Napoleon’s Options.

As usual Napoleon refrained from looking as if he was the one on the ropes and instead of falling back and consolidating his dwindling forces, he chose to maintain a straggling hold along the Rhine. This worm eaten shield consisted of the following:

First Line:

- Marshal Etienne–Jacques–Joseph–Alexandre Macdonald, Duke of Taranto. Around Düsseldorf with approximately 15,000 men.

- General Horace–Franҫois– Bastien Sébastiani. In the vicinity of the junction of the Moselle and Rhine rivers with some 5,000 men.

- General Charles–Antoine Morand. Around Mainz with 15,000 men.

- Marshal Auguste–Frédéric–Louis Marmont, Duke of Ragusa. Opposite Mannheim with approximately 15,000 men.

- Marshal Claude Victor, Duke of Bellune. South of Strasburg with 13,000 men.

Second Line:

- General Nicholas–Joseph Masion. Holding Belgium with a nominal force of 20,000 men but, in fact, with no more than 10,000 capable of active resistance.

- Marshal Adolphe–Edouard–Casimir–Joseph Mortier, Duke of Treviso. Around Troyes with part of the Imperial Guard, plus other troops concentrating. Eventually around 18,000 men.

- Marshal Michel Ney, Duke of Elchingen, Prince of the Moskowa. Around the southern extremity of the Vosges mountains with approximately 10,000 men.

Much further south, a force under Marshal Charles–Pierre–Franҫois Augereau, Duke of Castiglione assembling around Lyons was keeping up communication with Marshal Nicolas Jean de Dieu Soult, Duke of Dalmatia and Marshal Louis–Gabriel Suchet, Duke of Albufera who were endeavouring to hang–on to what was left of the French forces in Spain which were being slowly forced back to the Pyrenees by the Duke of Wellington, thus preventing many veteran units within their respective commands from being transferred to the Rhine. Also a tentative link was maintained with Napoleon’s stepson, Eugene Rose de Beauharnais, and his troops in Italy (around 30,000 effectives). There were also several thousand troops, many of which were lacking in military training, still garrisoning the frontier fortresses. [2]Maycock. F.W.O. Invasion of France, 1814. The Final Battles of the Napoleonic First Empire, page 34.

On the 9th of November Napoleon finally arrived in Paris full of bluff and bluster despite the desperate circumstances that now confronted him. After taking stock of the manpower situation with his usual disregard for the facts and ignoring the truth, on the 15th November he called for another 300,000 conscripts. The people of France, now fully aware of the human cost of supporting an empty empire and its insatiable emperor, answered the call to arms by not rushing to the recruiting stations. Many of those that did, albeit reluctantly, deserted in their hundreds on the way to the depots, forcing new laws to be invoked and severe punishments meted out, this in turn causing many young men to take to the forests and mountains rather than face death on the battlefield. [3]Ibid, page 13.

Napoleon’s one real ray of hope lay, ironically, with the allies themselves who became increasingly suspicious of each other’s motives and intentions as well as just what or who to put in his place after he was overthrown. On the 8th of November the Russian Tsar Alexander I and the Austrian Foreign Minister Prince Klemens Wenzel von Metternich had offered Napoleon an armistice and tentative peace terms which allowed him to retain France’s natural boundaries, the Alps, Rhine and the Pyrenees. They also allowed him to retain Belgium and Savoy as well as the left bank of the Rhine. He would have to relinquish his control over Holland, Spain, Germany and Italy. These terms were truly lenient, being a gamble it was considered Napoleon would not accept, Metternich stating in his memoirs:

“Any peace with Napoleon that would have thrown him back to the old boundaries of France, and which would have deprived him of districts that had been conquered before he came to power, would have only been a ridiculous armistice, and would have been repelled by him.” [4]Metternich, Memoirs, 1:225

True to form Napoleon thought of his own prestige and reputation to the detriment of the French people and flatly refused these terms. In response to Napoleon’s call for more troops the allies delivered their own manifesto to the French people stating that:

The French Government has just ordered a new levy of 300,000 conscripts. The justification set out in the new law are a provocation against the allied powers…

The allied powers are not making war against France…but against the domination which the Emperor Napoleon has for too long exercised beyond the borders of his empire, to the misfortune of both Europe and France… The allied sovereigns desire that France be strong, great and happy because a strong and great France is one of the fundamental bases of the whole order of the world (edifice sociale)…But the allied powers themselves want to live in freedom, happiness and tranquillity. They want a state of peace which through wise re-distribution of power and a just equilibrium will preserve their peoples henceforth from calamities beyond number which have weighed on Europe for twenty years. [5]From the manifesto produced by Baron Fain, Manuscript de Mil Huit Cent Quatorze. Quoted in, Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon: The Battle for Europe 1807 – 1814. Page 469 – 470.

Napoleon’s counter to this was to order still more recruits to the colours. On the 15th of November another 150,000 men were called up from the classes of 1803–1814, and four days later he summoned a further 40,000 from the classes of 1808–1814. In all, for the period from the end of October 1813 until the middle of January 1814, Napoleon attempted to collect a force of 936,500–only a fraction of these came forward, which gave him no more than 120,000 troops who ever saw combat. [6]Leggiere. Michael V, The Fall of Napoleon: The Allied Invasion of France 1813 – 1814, page 68 – 69

The Allied Plan.

Fully realising that, in view of the speed of French mobilization in early 1813, given time Napoleon could still, even if not in the numbers expected, manage to field a sizable force under his personal leadership, the allies would need to continue the campaign throughout the winter months of 1813–1814, allowing the French emperor no respite. Unfortunately although the allies were indeed poised to strike across the Rhine, their troops were in much need of rest and reorganisation before continuing the struggle. Also there was the problem of how the invasion on France should be conducted. Prince Karl Philipp Schwazenberg was retained as allied commander in chief but with his decision making always being subject to the scrutiny and meddling of both politicians and monarchs. This, plus his own dilatoriness and over caution, all helped to make any clear and fluid progress to the campaign hard to maintain.

After much debate and rejections a plan was finally agreed upon for the invasion of France whereby the Army of Bohemia, some 200,000 men under Schwazenbergs personal control, would move through Switzerland crossing the Rhine at Basel and Grenzach then move between the mountains of the Jura and Vosges via the Belfort gap, towards Langres. The Army of Silesia, 90,000 men under Field Marshal Prince Gebhard von Blücher, would cross the Rhine between Mainz and Koblenz, advancing south west towards Metz, Nancy and Joinville. The opportunist former French marshal, Jean–Baptiste Bernadotte, now crown prince of Sweden, but still harbouring grand ideas of becoming ruler of France himself, with The Army of the North, 120,000 men, was tasked with clearing Holland of the French while at the same time coordinating with General Levin Bennigsen’s Army of Poland, 50,000 men, in recapturing Hamburg and thus forcing the capitulation of Marshal Louis Davout, Duke of Auerstädt and Prince of Eckmühl’s French garrison. While these operations were taking place The Duke of Wellington with 90,000 men, together with a Spanish/British force of 50,000, would continue to force back the French armies under Marshal Soult, and Marshal Suchet, the former having fallen back into France, the latter now with his back against the Pyrenees Mountains in Northern Spain. [7]For full details of all Allied and French forces at the commencement of operations in 1814 see Leggiere. Michael V. The Fall of Napoleon, The Allied Invasion of France 1813 – 1814.

On New Year’s Day 1814 Blücher crossed the Rhine at Koblenz, Mannheim and Kaub, forcing Marshal Marmont with his 10,000 men to fall back, and on the 12th January he had blockaded the French fortress at Metz; also the detachments left to watch the fortresses of Thionville, Mainz and Luxemburg had reduced the effective fighting force of the Army of Silesia to 50,000 men. Meanwhile Schwazenberg had set up his headquarters at Basle and was slowly and cautiously pushing his forces forward towards the Langres Plateau. He was not happy with the way Blücher, as was his wont, was attempting to dash forward without adequate security for his flanks, and wrote to his wife, ‘Without placing any considerable force to guard the road from Châlons to Nancy they [Blücher and his Chief–of–Staff, General August Wilhelm Anton Gneisenau] rush on like mad bulls to Brienne. Regardless of their rear and flanks they do nothing but plan the fine parties they are going to enjoy in the Palais Royal.’ [8]Quoted in, Lawford. James, Napoleon, The Last Campaigns 1813 – 1815, page 73. The allied commander had good reason to be concerned. The impetuous Prussian had indeed advanced so rapidly that his forces had cut in ahead of the Army of Bohemia instead to keeping pace with it, and were now in danger of becoming isolated, a situation that Napoleon would be sure to take advantage of.

Brienne.

Napoleon left Paris in the early hours of January 25th, arriving at Châlons on the morning of the 26th. Noting with much annoyance that Marshal Victor had fallen back from St–Dizier he decided to concentrate the main body of his army, some 30,000 men, at Vitry. Ordering the requisition of thousands of bottles of wine and eau–de–vie, the French emperor stated that if all that was obtainable for the troops was champagne then it was better for them to drink it rather than the enemy. Thereafter he dictated the orders for the battle he was prepared to bring on in the morning:

‘Châlons–sur –Marne, 26th January, 9.45 in the morning.

The Emperor orders that the Duke of Belluno [Victor] takes up a position as close as possible to St–Dizier across the St–Dizier–Vitry road with his right flank resting on the Marne [River].

The Duke of Ragusa [Marmont] will deploy astride the main road half a league [roughly 2.5 English miles] behind the Duke of Belluno and remain ready to move instantly.

The Prince of the Moskva [Ney] with the 1st and 2nd Divisions of the Young Guard will take up a position across the road half a league or a league behind Marmont.

General Lefebvre with his cavalry [about 2,500 sabres] will take up a position behind the Prince of Moskva saddled and ready astride the road.

Imperial Headquaters will open this evening at a village behind the Duke of Bulluno.

The Army will be informed that the Emperor intends to attack tomorrow morning.

All baggage not required for the battle will be dumped between Vitry and Châlons.

The artillery is to be deployed ready for action.

Bread and brandy will be procured and distributed either at Vitry or where obtainable.

Localities will be prepared for dealing with casualties.

A reconnaissance will be made of the River Ornain and care will be taken to ensure the good condition of the road bridge and that at Vitry–le–Brûlé; a third will be constructed on a possible line of retreat.’ [9]Quoted in, Lawford. James, Napoleon, The Last Campaigns 1813- 1814 page 69.

Unfortunately Napoleon’s plans came to naught. On the 27th January Victor began to develop his attack at an early hour but after a brief clash at St. Dizier he found that the enemy had slipped away and old Blûcher was now ensconced in the château at Brienne, however his forces were not fully united, this in turn still gave Napoleon the chance to crush the Army of Silesia in detail before it made contact with elements of Schwazenbergs army and he set his army in motion towards Brienne. Blûcher still remained sceptical concerning the enemy’s intentions, even writing that the brush with the enemy at St.Dezier only proved how weak and badly organised the French were and that they would constitute no threat to his lines of communications, even stating that, “if he [Napoleon] tries it, nevertheless, nothing more desirable can happen for us; then we shall get to Paris without a blow.” [10]Petre. F. Loraine, Napoleon at Bay, 1814, page 19 On the 29th January the scales fell from his eyes when he received captured dispatches which informed him of the French movement. Although 18,000 troops under General Hans David Ludwig Yorck had been freed from the blockade of Metz by the withdrawal of Marmont’s French corps, and were marching to join him, Blücher realised that they were too far distant to be of any assistance in the forthcoming battle. Other elements of his army were closer but would still take time to be called back; therefore he immediately gave orders for the recall of General Baron Fabian Gotlieb von Osten–Sacken’s Russian Corps of 22,000 men, which had been pushed forward towards Lesmont. Until their arrival the troops directly available to oppose the French consisted of some 5,000 Russians and 24 cannon bivouacked around Brienne itself. These troops were under the command of General Zakhar Dmitrevitch Olsufiev. Luckily for Blücher the advance guard of General Wittgenstein’s 6th Corps, consisting of 3,000 cavalry under General Peter Petrovich Pahlen III, was approaching and proved a welcome boost in manpower.

The weather during the days up until the 28th January had been cold with heavy frosts at night and freezing temperatures during the day. Now a thaw had set in turning the roads into ankle deep mud trails and the fields into bogs. At 2.00 p.m. on the afternoon of the 29th January the French attack began but went in piecemeal owing to the state of the ground, which slowed down the movement of their cavalry and artillery. Not to be denied, the young French conscripts fought with bravery and determination, finally capturing the town and forcing the old Prussian field marshal to quit the chateau of Brienne-where he had been taking advantage of its wine cellar-scampering down a back staircase, just in the nick of time before being taken prisoner. The battle cost Napoleon around 3,000 killed and wounded. Blücher’s losses amounted about 4,000 and he fell back east through the village of La Rothiere pursued by the French.

A Bloody Nose- La Rothiere

After the battle of Brienne the weather once again became cold, with plummeting temperatures. Blücher, now united with Sackens corps, had around 26,000 men and finally halted south of La Rothier aligning them on the high ground in front of the village of Trannes. Here he was joined during the 30th-31st January by Prince Eugen of Württemberg’s 1st Corps, General Count Maros–Nemeth Ignaz Gyulai’s 3rd Austrian Corps together with the combined corps of Russian and Prussian Guards, all from Schwazenberg’s Army of Bohemia, with the Austrian 1st Corps under General Count Hieronymus Karl von Colloredo–Mansfeld marching to threaten the road to Troyes and the Bavarian Corps of General Karl Philipp Josef von Wrede, together with the Russian corps under General Peter Khristianovich (Ludwig Adolf) Wittgenstein approaching from Joinville. This gave Blücher some 80,000 men on the field, with a further 30,000 closing in.

Napoleon, with less than 50,000 men, had taken up a position watching Blücher with his centre at La Rothiere, his right flank anchored on the River Aube at the village of Dienville, and his left flank spread out in a straggling line running through La Rothiere in the centre to the village of Giberie, the whole French front extending over 9 kilometres. Not fully comprehending the strength of the forces gathering against him, Napoleon considered that an attempt would be made to outflank him westward and, on the 1st February, Marshal Ney begun to withdraw his forces towards Troyes only to be recalled when news arrived that the allies were about to attack in strength.

The decision to fight a battle, and a defensive one at that, shows how desperate Napoleon was to gain a victory as soon as possible to boost the moral of his young recruits, as well as to calm the panic already caused across the country by the invasion. However, to take such a risk knowing full well that he was faced not only by superior numbers but also by soldiers of proven quality, plus having to hold a position far too extensive for the troops available, does make one wonder just what was going on in Napoleons head.

The battle began just after 1.00p.m. on the afternoon of February 1st and raged on amid heavy snow storms until darkness enabled the French to retire in reasonably good order but their spirits at low ebb, this being Napoleons first defeat on French soil. Each side had lost over 5,000 men with the French leaving 60 cannon either captured or destroyed on the field.

Tsar Alexander was so overjoyed by the result that he sent personal messages to Blûcher and Sacken congratulating them on a great victory. Sacken himself in his report on the battle even got carried way to the extent of writing, ‘On this memorable and triumphant day Napoleon ceased to be the enemy of mankind and [Tsar] Alexander can say, I will grant peace to the world.’ [11]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoeon. The Battle for Europe 1807 – 1814, page 481. Hasty words, like pride, come before a fall.

Riding a Punch.

There was no getting away from the fact that the French Emperor had indeed suffered a very severe battering, with many young recruits quitting the army during the retreat from the bloody snow covered fields around La Rothiere. However, Napoleon was still able to hold things together due to his charismatic personality and overall control of the French forces. True, his well conceived offensive plan had ended in failure, but he had not suffered the crushing defeat that would have led to his capitulation. The allies were so carried away with their success that they failed to follow it up by an aggressive and rapid pursuit, and they certainly had enough troops available who had not been engaged in the battle to do this, but spent the day after the battle celebrating, with Blücher once again taking himself off deep into the wine cellars of the Brienne chateau, where the Tsar found him selecting the best bottles for his personal consumption. [12]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon. The Battle for Europe 1807 – 1814, page 482.

Finally managing to knuckle–down to the task of continuing the campaign, the allies held a council of war at Brienne where it was decided, after much heated debate, that the armies of Blücher and Schwazenberg should again separate. This decision was reached ostensibly because of the problem of supply, which would prove a severe handicap with so many troops concentrated in one grouping, but also one suspects it had just as much to do with the personalities and temperaments of the two army commanders. The final plan agreed upon was:

That the Allied forces shall separate anew; that the Silesian army of Field–Marshal Blücher shall at once march from here to Chalons, unite there with the scattered divisions of General Yorck, von Kleist and Count Langeron, and press on along the Marne past Meaux to Paris, while the main army turns towards Troyes, and likewise presses on to Paris along both banks of the Seine. [13]Quoted in, Maycock. F.W, O., Invasion of France, 1814. The Final Battles of the Napoleonic First Empire, page 53.

Recovery.

By the 3rd February Napoleon had withdrawn his dispirited army to Troyes from where he dispatched numerous letters to his brother Joseph, whom he had placed in charge of his affairs in Paris, urging him to raise new regiments and hurry forward the two divisions that had been detached from Marshal Soult’s army to join him by forced marches. Meanwhile he continued to withdraw to Nogent–sur–Seine where he consolidated his position and, like a cat watching a mouse hole, awaited a chance to pounce-he did not have to wait long.

After a brief clash at St Dizer Yorck corps advanced as far as Chalons, forcing part of Marshal Macdonald’s command to evacuate the city and fall back to Epernay and Chateau Thirrey, keeping to the main road to Paris, on the left bank of the River Marne. Meanwhile an ebullient Blücher, only too happy to be once more free to do his own thing, took Sacken’s corps and Olssufiev’s division to Rosny and thence on to Fere Champenoise, then striking northward, sending Yorck and Sacken on towards Montmirail to continue the pursuit of Macdonald, he paused at Bergeres to await the arrival of Kleist’s corps. [14]Maycock. F.W.O., Invasion of France, 1814.The Final Battles of the Napoeonic First Empire, page 52.

While Blücher was deluding himself with the thought of dashing on to Paris, Schwazenberg, ever plagued by visions of the Corsican ogre suddenly making a thrust against his line of communication, strengthened his forces towards his left flank, while tentatively pushing out a probing column towards La Guillotiére on the River Barse, just south–east of Troyes. Here they clashed with the veterans of Marshal Mortier’s Imperial Guard who Napoleon had sent out on a recognisance in force, and were driven back in much confusion and disorder. This action confirmed Schwazenbergs belief that Napoleon was about to attack and he took up a strong defensive position at Bur–sur–Seine where, between 9th–10th February, he concentrated his forces. [15]Lawford. James, Napoleon. The Last Campaigns 1813-1815, page 81

Schwatzenberg sent an urgent message to Blücher informing him that he was calling back Wittgenstein’s corps to join him to bolster his forces for the impending clash with Napoleon, but rather than being perturbed by this news the old hussar considered that with the French Emperor’s main effort seemingly now being against the Army of Bohemia, his own Army of Silesia would be free to continue its advance almost unopposed, and he had therefore dispersed his army over too wide an area to allow for any rapid concentration.

Napoleon was beset by a plethora of bad news pouring in regarding events taking place elsewhere. His brother–in–law, former Marshal and now King of Naples, Joachim Murat had gone over to the Allies, Antwerp was cut off, Brussels had been taken and at Chatillion, where his Foreign Minister Armand Caulaincourt was still attempting to obtain a good deal for his master at a peace conference, it had been decided to offer the French Emperor only the original pre 1789 borders of France and not her “natural boundaries.” [16]Espisito and Elting, A Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars, page/map 147. Nevertheless, despite these bad tidings, the astute general took over from the ermine cushioned monarch, and Napoleon conceived a plan which almost turned the tables.

On the 9th February, by a rapid march, Napoleon arrived at Sezanne with 35,000 men, hovering menacingly on Blücher’s flank, the latter being totally unaware of his presence, while Schwazenberg was equally ignorant of the enemy’s intentions, still being under the impression that Napoleon was at Nogent and asking Blücher for reinforcements, which were duly dispatched. Thereafter, early on the morning of the 10th February, news began to arrive at Blücher’s Head-Quarters that Napoleon was at Sezanne, but even then nothing was done to recall the troops sent to Schwatzenberg, or to draw his scattered forces closer together. Indeed, it would appear that Blücher held his opponent in such contempt that he considered him a spent force and no more than a “fugitive from justice,” [17]Ibid, page/map 147. still ordering Sacken to continue his pursuit of Macdonald and leaving a detachment of around 4,000 under Olsufiev out on a limb at Champaubert. Here, on the the 11th February, Napoleon struck, killing and wounding over 800 and capturing some 1200 of Olsufiev’s force, while driving the remainder back in total confusion to join Blücher, who at last began to send out urgent messages to Sacken and Yorck urging them to rejoin him, plus cancelling his previous orders to Kleist and General Peter Mikhailovich Kaptsevich whom he had instructed to march on Sezanne and were now directed to Vertus. However, Blücher’s attempt to pull his army together proved too late, Napoleon had already positioned himself between the Army of Silesia’s scattered corps. [18]Maycock. F.W.O. Invasion of France, 1814. The Final Battles of the Napoleonic First Empire, page 61.

Having shattered Olsufiev, Napoleon now turned to deal with Yorck and Sacken. He ordered Marshal Marmont to keep an eye on Blücher and directed Marshal Macdonald to countermach east. Marshal Oudinot was also ordered to comply with a general concentration around Montmirail, with Marshal Mortier’s Old Guard joining them from Sezanne. [19]Esposito and Elting, A Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars, page/map 148.

The best plan would have been for Sacken to have pulled back north of the River Marne and there link up with Yorck at Château Thierry, and Yorck himself tried in vain to persuade Sacken to adopt this course of action, but to no avail. Blücher’s orders to Sacken had been to march back towards Champaubert where he was supposedly to link up with Blücher, but these orders had been issued before the old Field Marshal had any real notion of where Napoleon was heading, and were no longer relevant to the present circumstances, which Sacken was unaware of himself, and thus he set out on the night of 10th February not knowing that Napoleon was already across the road down which he was marching. [20]Lieven. Dominic, Russia Against Napoleon. The Battle for Europe 1807 to 1814, page 487

At around 11.30 a.m. on the morning of the 11th February, Sacken’s advance guard arrived at Viels–Maisons, just west of Montmirail, amid a steady fall of cold rain, and here they clashed with the French advance guard. Soon a general engagement was in full swing with the French advance being kept in check by forty cannon drawn up across the Russian front, while further south at Marchaise a desperate battle was fought around the village, which was taken and retaken several times. While the fight raged on Sacken eagerly awaited the arrival of Yorck’s corps, which he expected would soon be joining him from Château Thierry. Unfortunately no help arrived; a message from Yorck arrived informing Sacken that owing to the deplorable state of the roads only a small portion of his infantry (General Georg von Pirch II with 4,000 men) would be able to get close to the battlefield to aid the Russians.

Having held Napoleon in check, Sacken realised that to continue the fight would result in the possible annihilation of his entire force, and during the evening and night he skilfully withdrew his corps, together with most of its artillery and baggage along the mud clogged road back towards the Marne River at Château Thierry. Lievin gives a good account of the condition of the Russian troops as they trudged along in the rain and darkness:

…Fires were lit every two hundred paces to guide the infantry along the way. In the drenching rain, with their muskets useless, the Russian infantry had both to march in compact masses to keep the enemy cavalry at bay and on occasion to break ranks in order to pull their artillery out of the mud. Though very outnumbered, Ilarion Vasilchikov [He commanded the cavalry of the Army of Silesia] and his splendid cavalry regiments greatly helped to protect the infantry and drag away most of the guns. Napoleon pressed the retreating Russians hard and by the time they finally got across the Marne they had lost 5,000 men. The Russian casualties would have been far higher had it not been for the courageous rearguard actions of Yorck’s Prussian infantry [Pirch II]. Sacken was a hard bitten old campaigner and ‘politician.’ The day after the battle, finally tracked down by his nervous and exhausted staff, who had lost him in the course of the retreat, he was as calm and self assured as always. In the best traditions of coalition warfare, in his official report he blamed the defeat on the Prussians, and in particular on Yorck’s failure to obey Blücher’s orders and support him in good time. [21]Lievien. Dominic, Russia Against Napoleon. The Battle for Europe, 1807 to 1814, page 488. See endnotes. The description of Sacken the day after the battle is from Bernhardi,Denkwürdigkeiten, vol. … Continue reading

There can be little doubt that, although Blücher was the orchestrator of the disaster that befell his subordinates, Yorck’s failure to support Sacken in strength at Montmirail only compounded the issue. Napoleon had done serious damage to three of the scattered detachments of the Army of Silesia, costing it over 5,000 casualties and making a serious dent in its morale. For his part the French emperor took up lodgings in Château Thierry, planning his next move and allowing his troops a brief rest period while the bridges over the Marne were repaired. [22]Maycock. F.W.O., Invasion of France 1814. The Final Battles of the Napoleonic First Empire, page 63.

On the 13th February Napoleon, having decided to move on Schwazenberg, suddenly received new that Blücher, with the corps of Kleist and Kaptsevich (16,000 men), and under the false impression that the French had already swung south and were well on their way to confront the Army of Bohemia, was marching directly down the road to Vauchamps. Here, on the morning of 14th February, the old Field Marshal ran head–on into Napoleon’s main force. Realising that he was outnumbered and having very few cavalry, Blücher ordered an immediate retreat to Etoges, keeping his artillery on the road while his infantry, forming squares, retired back across the fields on either side. Despite being harried persistently by the numerous French cavalry, and although losing over a third of his force, Blücher managed to get way without total ruin, nevertheless, during five days of fighting his army had suffered a series of defeats which had cost over 17,000 men and several pieces of artillery and it was only due to the discipline of his troops and their devotion to him personally, that Blücher managed to keep it together.

Pipe Dreams.

With his usual talent for overestimation and under valuation, Napoleon had already written to his brother Joseph on 11th February declaring that: ‘The enemy army of Silesia no longer exists: I have totally routed it.’ And even a week later when he was in a better position to gauge the effects of the various battles and manoeuvres, he still deluded himself as to the real situation when he wrote to Eugene de Beauharnais that he had destroyed the Army of Silesia and taken over 30,000 prisoners. In fact, although the losses to Blücher’s army had been heavy, he was being more than compensated by the arrival on the 18th February of Langeron’s Corps (8,000 men) and the tidings that he would soon be joined by other Russian and Prussian troops who had been relieved of blockading the fortresses and were now marching to bolster his numbers. These, plus hundreds of liberated captives as well as missing men returning to the colours, soon filled up the ranks making Blücher’s army as strong as it had been on 10th February. [23]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon. The Battle for Europe, 1807 – 1814, page 489. See also, Correspondance de Napoleon Ier, 32 vols. Paris, 1858 – 70, vol. 27, Paris, 1869, no. 21295, … Continue reading

Schweazenberg.

Considering Blücher’s army a spent force, Napoleon now decided to turn his attention to defeating Schwazenberg, and it is worth reading what the German Staff historian’s opinion of that commanders abilities were during the 1814 campaign:

Political considerations came first and remained so during the entire campaign for Schwazenberg, while strategy took a backseat. The political restraints was represented by Metternich, who found no counter–weight in the military elements in the Austrian headquarters. Schwazenberg himself was far from being a commander and thus hardly made the pretence to be one. He relied on the ideas of his general–quartermaster, Langenau, a man who was just as erudite as he was an impractical adherent of the old school, for which the experience of the Napoleonic Wars were ignored, and which looked at a battle as only a crude, dire expedient, unworthy of any educated field commander. The Austrian field commander had to subordinate his art of war to Austrian politics, which did not want Napoleon annihilated, and Schwazenberg complied. Blücher and Gneisenau were opposed to such. The characters in Austrian headquarters were otherwise. Obviously those men did their duty, and one can completely assume that Radetzky [General Joseph von Radetz Radetzky, Austrian and Allied Chief of the General Staff] had serious internal struggles in attempting to persuade Langenau, who was a total theorist. [24]Quoted in, Leggiere. Michael V., The Fall of Napoleon. The Allied Invasion of France, 1813 – 1814, page 139 – 140. See, Janson, A. Geshichte des Feldzuges 1814 in Frankreich. 2 vols. Berlin, 1903 … Continue reading

Schwazenberg, now with his forces concentrated around Troyes, received news that Napoleon had marched off to the north to confront Blücher. Finally feeling able to continue his advance, much to the relief of Tsar Alexander, on 11th February the Army of Bohemia started to move, although meeting with some stiff resistance from Victor and Oudinot’s weak forces who fell back to the River Yeres. On the 15th February, with his headquarters established in Nogent, Schwazenberg brought up his Russian reserves to the south bank of the River Seine opposite Bray, but with Wittgenstein being so impatient to get on that he pushed his corps further on down the road to Paris as far as Provins. [25]Maycock. F.W.O., Invasion of France 1814. The Final Battles of the Napoleonic First Empire, page 70 – 72.

Turning south with a speed reminiscent of his campaigning days as a young general in Italy, Napoleon went heads down to confront Schwazenberg, who had scattered his various corps over a distance of 50 kilometres, as he believed that this was the only way to move and feed his army. The problem was that with very few good lateral side road connections in this part of the country the concentration of his forces would prove slow and thus vulnerable to a sudden attack. [26]Lieven. Dominic, Russia Against Napoleon. The Battle for Europe 1807 – 1814, page 491.

On the frosty morning of 17th February Napoleon struck, driving back Wittgenstein’s troops in total confusion and causing a panic which spread though the whole of Schwazenberg’s army, sending it tumbling back as fast as it could travel towards Troyes and Bar–sur–Aube. Thus, within less than a month, Napoleon had knocked the stuffing out of the initial invasion of France and done much to restoring his reputation as the supreme warlord. [27]Ibid, page 491. However, the victorious emperor was also the great gambler, who, even with the odds still obviously stacked against him, was always prepared to raise the stakes.

New Plans.

On the 25th February at Bar–sur–Aube, after taking sufficient precautions against any possibility of once more being caught in a Napoleonic embrace, the allied leaders came to, as usual, a compromised agreement concerning their next moves. The Tsar was most anxious that the offensive should be resumed without delay and suggested that since Bernadotte was not pressing his advance in Belgium with any haste, then the two corps of Bulow and Winzingerode could be put to better use if they were transferred to Blücher. However, it was made clear to the Russian emperor that knowing the temperament of the Swedish Crown Prince he would possibly vacillate so much in allowing this to occur that the whole campaign could well grind to a halt. The Tsar next suggested that he should himself support Blücher with the Russian Imperial Guard and Wittgenstein’s corps for an immediate march on Paris, an idea that was strongly supported by the Prussian king who also proposed to join him with the Prussian guard. This idea was also set aside when a panic stricken Schwazenberg made it clear that with the withdrawal of the Russian and Prussian contingents the Army of Bohemia would be too weak to conduct effective operations and therefore be forced to retire to the Rhine. Finally the British Foreign Minister, Viscount Robert Stewart Castlereagh, representing British interests at the war council, and because effectively Britain was bank rolling the whole war, demanded that, because the consensus of opinion agreed that Bulow and Winzingerode should indeed join Blücher’s army, then Bernadotte would have his monthly subsidy withheld if he did not concur with the councils decisions–this bought Bernadotte to heel and consequently the Army of Silesia’s strength was increased to over 100,000 men. [28]Maycock. F.W.O., Invasion of France 1814. The Final Battles of the Napoleonic First Empire, page 80- 81.

It was now agreed that Schwazenberg would detach sufficient troops from his army to protect its line of communication with Switzerland against any threat that may be posed by Marshal Augereau’s French forces gathering around Lyon, while the Army of Silesia and the Army of Bohemia would act independently but also in a similar fashion to the one adopted during the 1813 campaign in Germany, whereby if one army was opposed to Napoleon it would fall back while the other carried on towards Paris. When Napoleon swung his weight against the advancing army the one that was withdrawing would press on towards Paris. This plan allowed for a slow but careful march on the French capital without becoming too bogged down in administrative complications. Once both armies were within striking distance of their goal they would unite and offer a decisive battle. [29]Lawford. James, Napoleon. The Last Campaigns of 1813 – 1815, page 91.

While Schwazenberg remained temporarily on the defensive, Blücher’s army now advanced north threatening Paris. He would join forces with the corps under Bülow and Winzengerode, now detached from Bernadotte’s army, who were now marching towards Soissons. Also a newly constituted corps of Saxon’s was on its way to bolster Blücher’s army. Nevertheless, Tsar Alexander still cautioned the Prussian Field Marshal against any overzealous movements that might result in his receiving another mauling by Napoleon. His letter to Blucher ending with the words, ‘…as soon as you have coordinated the movements of your various corps we wish you to commence your offensive, which promises the happiest results so long as it is based on prudence.’ [30]Quoted in, Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon. The Battle for Europe, 1907 – 1814 page 498. The extract is taken from RGVIA, Fond 846, Opis 16, Delo 3399, fos. 131 ii – 132ai. SIRIO, 31, … Continue reading

The French forces opposing Blücher were commanded by Marshal Marmont and Marshal Mortier, the latter having joined forces with the former , their united strength only amounting to around 10,000 men. Keeping their troops well in hand the two marshals retreated with great skill and crossed the River Marne at Trilport, thence they fell back towards Meaux, only 34 kilometres from Paris. In his turn Blücher switched his line of march back towards La Ferté–sour–Jouarre, constructing a pontoon bridge across the Marne there and then once again turned his columns towards Meaux. It was during this time that he received new that Napoleon was on his way north. [31]Lawford. James, Napoleon, The Last Campaigns, 1813 – 1815, page 91.

(Dept of History, United States Military Academy).

On the 29th February Napoleon had the main body of his army concentrated in the area between Sezanne and La Ferte Gaucher from where he intended to strike at Blücher the next day in conjunction with Marmont and Mortier. It is little wonder that the old Prussian became concerned; if indeed the French were closing in for the kill then it was imperative for him to join up with Winzingerode’s and Bülow’s corp which were besieging Soission. Blücher had to decide if he should stand and fight, or retreat across the River Aisne before Napoleon struck his blow. On the 3rd March, taking into consideration the fact that his army was still a little unpredictable after its recent mauling by the French, Blücher ordered his baggage train to leave straight away towards Fismes, with the rest of the army following later in the afternoon after resting. They would then cross the river via pontoon bridges placed near Vailly and continue in the direction of Berry–au–Bac. [32]Lawford. James, Napoleon, The Last Campaign, 1813 – 1815, page 91 Blücher sent urgent orders for Bülow and Winzingerode to join him without delay at Ourq, where he intended to give battle.

Soissons.

At around 7.00 p.m. on the evening of 4th March Napoleon reached Fismes with his Old Guard, two divisions of Young Guard under Marshal Ney and General Etienne–Marie–Antoine–Champion de Nansouty’s Imperial Guard Cavalry, who had fought a spirited action at Château–Thierry on the 3rd March. Taking stock of the situation (as he saw it) Napoleon settled on a plan that would destroy Blücher’s army or at least push him back northward while he marched on Chalons from where he anticipated collecting the garrisons of the various fortresses in the Rhine province, thus increasing his army by several thousand men. He would then move to cut Schwazenberg’s communications causing the Army of Bohemia to become isolated. [33]Maycock. F.W.O., Invasion of France 1814. The Final Battles of the First Napoleonic Empire, page 88.

Meanwhile Blücher’s forces were crossing the Aisne River and Napoleon, expecting to catch him while he was still around Fismes realised that the old hussar was possibly making for Laon and therefore would be using the crossing at Soissons to reach his goal. By swinging north from Fismes and crossing the Aisne there the French emperor considered that he might just reach Laon before him. However, these were only Napoleon’s speculations and, with his usual overestimation of the “actual” situation on the ground, he expected that the small French garrison at Soissons would be able to delay Blücher long enough for him to win the race to Laon. What he did not take into consideration was the panic caused by Winzingerode ruse to bombard Soissons into submission if the commander of the garrison, General Jean–Victor Moreau, did not surrender the town immediately. That he did so has led to one of the great debates surrounding this campaign and it is worthwhile considering the effects it had on the battle of Caronne, and indeed if the battle would have been fought at all given different circumstances?

Colonel Lawson in his work: “Napoleon. The Last Campaign’s 1813–1815”, states:

It has been asserted that the surrender of Soissons saved Blücher, and a stream of abuse has been directed at the unfortunate garrison commander, General Moreau, for sparing the town from a storm. Winzingerode and Bülow, having exhausted the efforts of their 45,000 men besieging a garrison of about 1,000 [Poles], had every reason to exaggerate the importance of their capture. Napoleon’s fury–he wrote, though without effect, that Moreau should be shot–stemmed in the first place from the belief that the defence was not as stubborn as it might have been, and secondly from his intention to use the bridge for an advance on Laon. As for Blücher’s predicament, Bülow had already constructed a pontoon bridge at Vailly, nine miles to the east of Soissons and had the material to build more, while Blücher had with him his 50 canvas pontoons. Napoleon was still about 12 miles away [19 kilometres]. Had he got closer, the Prussian might have lost some tail–feathers, but that would have been all; and had Blücher persuaded Bülow and Winzingrode to come south of the river, Napoleon might have found himself gravely outnumbered. When Winzingrode, having put him in peril in the first place, explained to Blücher how grateful he should be that Bülow had saved him, Blücher nearly exploded. [34]Lawson. James, Napoleon. The Last Campaigns 1813 – 1815, page 91.

Petre states:

...he [Napoleon] had nothing nearer to Blücher than Grouchy’s cavalry, which was opposed to Blücher’s. The nearest French infantry of the Emperor’s own force was at Fismes some seventeen miles [27 kilometres] from Soissons, and about ten [16 kilometres] from the Vailly footbridge. Under these circumstances, how is it possible to believe that Napoleon could have cut off any large portion of Blücher’s army south of the Aisne by the morning of the 5th [March] , the latest time at which the allies would have been crossing, even if they had not had the bridge at Soissons? Our conclusion, therefore, must be contrary to that which represents Blücher as saved solely by the capture of Soissons. At the same time, the possession of the bridge certainly saved some anxiety. [35]Pete. F. Loraine, Napoleon at Bay. The Campaign of France 1814, page 115.

While Maycock writes:

Undoubtedly the possession of the stone bridge over the Aisne at Soissons was of the utmost convenience to Blücher, but a careful comparison of the times and distance tends to prove that in any case the army of Silesia could have crossed the Aisne by the means of pontoon bridges without interference, except from the hostile cavalry. As a matter of fact, the Emperor had entirely failed to divine Blücher’s intentions and had made a purposeless march eastward, under the impression that his opponent was endeavouring to reach Reims. [36]Maycock. F.W.O., Invasion of France 1814. The Final Battles of the Napoleonic First Empire, page 89.

With all of the above in agreement regarding the question of holding Soissons, then the French historian, Henry Houssaye (1848–1911) would seem to be in the minority when he states:

The Emperor’s anger was natural; [37]He had ordered Moreau to be shot, which was not carried out owing to Napoleon’s abdication. he himself said that the capitulation of Soissons saved Blücher from disaster. This conclusion is drawn from French documents, and also borne out by the majority of Russian and German documents. [38]Houssaye. Henry, Napoleon and the Campaign of 1814, page 137.

It would therefore seem that, although a very thorough history of the campaign is given by Houssaye, he does tend to overlook Napoleon’s errors, or at least make excuses for him by pointing the figure at Moreau. Of course, one would expect the Emperor himself to pass–the–buck, always blaming others for his own mistakes.

Craonne.

The ‘Fog of War’ played a part in the plans of both protagonists during this time. Blücher was not fully aware of Napoleon’s strength or intentions; likewise, the French Emperor was also under the impression that the enemy was retreating when, in fact, just the opposite was taking place; Blücher himself was planning to go over on the offensive. He had chosen to temporarily abandon his communications with the Rhine which left his only line of retreat though Laon; that town became of the utmost importance and he was determined to bring Napoleon to battle at the first opportune moment. [39]Maycock.F.W.O., Invasion of France 1814. The Final Battles of the Napoleonic First Empire, page 90.

Early in the cold dawn light of the 5th March the troops under Napoleon began crossing the River Aisne at Berry–au–Bac, while further west Blücher moved towards the village of Craonne. Thus we have the unusual situation whereby Napoleon was marching towards Paris with Blücher awaiting his attack with his back towards the French capital.

The position chosen by the Prussian Field Marshal was well suited to defence, however passivity was never part of Blücher’s vocabulary; rather than just await the French attack and hold his ground, the old man had worked out a plan, albeit one that never did reach full fruition, whereby part of his force would contain Napoleon’s onslaught, while a large force, including over 10,000 cavalry, would strike the French right flank and rear in a enveloping manoeuvre.

Since the whole terrain, with the exception of the plateau which the road from L’Ange–Gardien to Corbény crosses, known as the Chemin des Dames, has changed considerably since the time of the battle. I herewith give a description of the battlefield taken from F. Loraine Petre’s work: “Napoleon at Bay. The Campaign of France 1814”. Petre had visited the battlefield as a guest of the French army in 1912 and took part in divisional manoeuvres around the area of Soissons, Laon and Berry–au–Bac. The countryside in 1912 was much as it had been one hundred years before.

…Here it will be convenient to describe the country in the triangle Soissons, Laon, Berry–au–Bac which was to form the theatre of operations during the next few days.

The so–called Chemin des Dames, starting from a point on the Soissions–Laon road near the inn of L’Ange Gardien, runs eastward along a continuous ridge to Craonne near the eastern end of the ridge. Just west of that village it descends along the southern face to Chevreux, and rises again slightly to join the Reims–Laon road at Corbény.The ridge averages an elevation of some 400 feet [121.9 meters] above the valley of the [River] Aisne. It varies much in width, from a couple of hundred yards or less[182.88 meters], where valleys from the north and south nearly meet, to two miles[2.3 kilometres] or more along the spurs on either side. The spurs on the north side are generally shorter than the south, and the slope is steeper to the valley of the [River] Lette, or Ailette, a stream which runs generally parallel to the Aisne to join the [River] Oise. The slopes on this side are much wooded, and the valley is marshy.

North of the Lette are more hills of about the same elevation as those on the south, but forming a less distinct ridge. These northern heights again fall to a wooded marshy plain extending over some four miles [4.6 kilometres] up to Laon. West of the Siossons–Laon road is a hilly country, the eastern border of which is within two or three miles [3.9 kilometres] of Laon. North of Laon, and east of the Reims–Laon road, the country is practically level.

Laon itself stands on an isolated hill rising some 350 feet[106.6 meters] above the plain…. the town occupies the sumit, and even now [1912] there remains much of the old walls which once made it a very strong fortress. At the foot of the hill are several suburbs, of which the most important for our purpose are Semilly at the south–west corner, and Ardon to the south, the latter traversed by a marshy brook of the same name which flows to join the Lette beyond the road to Soissons some five or six miles [9.6 kilometres] south–west of Laon. The Soissons–Laon road runs through and over hills till it reaches the plain south of Laon. The Reims–Laon road runs mostly outside the hills which only cross it with outlying spurs for a mile or two on either side of Festieux. The chief distances, as the crow flies, are: Soissons to Laon 18 miles [28 kilometres]; Soissons to Berry–au–Bac 26 miles [41.8 kilometres]; Berry–au–Bac to Laon 18 miles [28 kilometres].

The plain south of Laon, between the Reims and Soissions roads, is extremely difficult for transverse communications, owing to the marshy fields in which, though the ground looks solid enough at a distance, a horse will sink to its hocks. The villages in the neighbourhood are generally defensible. Some of them, Bruyéres for instance, are old fortified villages with some of the walls still standing [in 1912]. [40]Petre. F. Loraine, Napoleon at Bay. The Campaign of France 1814, page 119 – 121.

Blücher placed General Mikhail Semenovich Vorontsov, commanding Winzingerode’s troops, backed up by General Sacken’s infantry, on the Craonne plateau to block Napoleon’s advance. Meanwhile Winzengerode, with 10,000 cavalry and Kleist Prussian corps would move around the French northern flank and attack them from the rear. General Louis Alexander Andrault Langeron would leave part of his corps guarding Soissons with the remainder falling back on Aizy, while Bülow’s corps would cover Laon.

Unfortunately the plan was flawed; not only would Bülow and Langeron’s corps not be present to add their decisive weight on the battlefield, but the ground that had to be covered by the flanking columns had not been reconnoitred correctly and proved to be very hard to negotiate. The broken nature of the terrain, together with hills, rocks, streams, and marshland proved very difficult for the cavalry and artillery and slowed their advance considerably. Also Blücher’s choice of placing Winzengerode in command of the flanking manoeuvre did not help matters when it came to speeding things up. [41]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon. The Battle for Europe 1807 to 1814. page 499. Nothing daunted the Russian infantry under Vorontsov and Sacken, the latter drawing up his battalions some 1,000 meters to the rear of Vorontsov’s line, with their uniforms and boots starting to fall to pieces and they themselves in sore need of rest and shelter, prepared to meet the enemy with their usual gritty determination.

Their position ran north to south across the plateau, straggling the Chemin de Dames highway, about 5 kilometres west of the village of Craonne, which was held by several companies of Russian infantry. The sides of the plateau fell way steeply to the north and south, the northern slopes being thickly wooded and the bottom land marshy. At its most constricted point stood the farm of Heurtebise (Windswept), around 4 kilometres from Craonne village; the farm was loop holed for defence and garrisoned by the Russian 14th Jäger regiment whose ranks were filled with elite sharpshooters made up from the disbanded combined grenadier battalions of Winzengerode’s Army Corps. [42]Lieven. Dominic, Russia against Napoleon. The Battle for Europe 1807 to 1814, page 500.

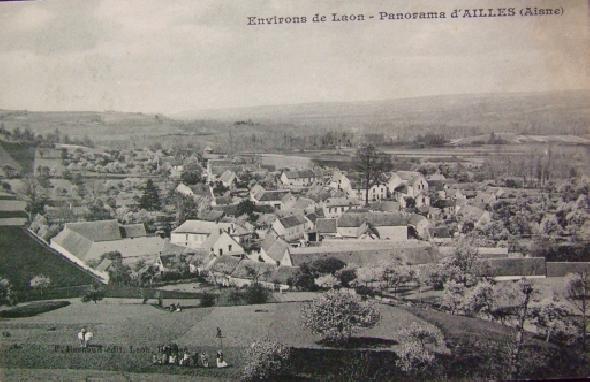

The Abbey of Vauclerc and the village of Ailles situated in the valley north of the plateau were also occupied by Russian light troops who were ordered to contain the enemy for as long as possible before falling back up the slopes to their main position. The right of Vorontsov’s line, as far as the village of Vassonge, was covered by a few squadrons of cavalry bolstered by several battalions of infantry, some of the latter spread out in skirmishing order. 36 cannon were sighted in front of the Russian main position with others covering the approaches to the plateau on both sides, plus 30 held in reserve, a total of 96 guns. Blücher, with a large body of cavalry, remained with Sacken’s reserve infantry. In all there were about 30,000 troops available, but of these only the 16,000 infantry under Vorontsov’s and 2,000 cavalry under General Illarion Vasilievich Vasilchikov were heavily engaged. The position, at first glance, seemed ideal for repelling any enemy attack, however it was susceptible to being turned on both flanks by hostile forces simultaneously advancing on the plateau from the north and south valley’s, while strong pressure was being applied along the front. The absence of Langeron and Bülow’s corps meant that there were insufficient troop’s available to cover these eventualities.

Napoleon had ordered all of the troops under his immediate command to concentrate at Berry–au–Bac, and called back Mortier and Marmont, who had attempted and failed to take Soission, to conform to the movement. Thereafter the Emperor himself arrived at Berry–au–Bac at 4.00 p.m. on the afternoon of the 6th March and upon being informed that the enemy had been seen on the heights of Craonne he immediately ordered a reconnaissance of the position. The troops sent forward consisting of a battalion of the Old Guard who soon encountered strong opposition from the Russian 13th and 14th Jäger Regiments around the Abbey of Vauclerc and in the village of Craonne itself, this proving so staunch that Napoleon called up Marshal Ney with the 1st Young Guard Division (these troops, 1,000 strong, were like the rest of the various battalions, regiments, brigades and divisions making up the French army at this period, were all vastly under strength) to their support. These troops under General of Division Claude–Marie Meunier came pushing through the frozen marshy ground in the Corbeny wood, driving the Russian defenders of the Abbey of Vaucler back up the steep hillside to the farm of Heurtebise. Here the battle around the farm and outbuildings lasted until 7.00 p.m., with first one side and then the other being driven out, until finally being firmly back in possession of the Russians; the struggle coming to a spluttering halt after orders were received from Napoleon to cease fighting for the evening. [43]Hilaire. St, History of the Imperial Guard, Book XVI Chapter II. The Guard During The Campaign Of France, In 1814. Taken form, Military Subjects: Organization, Strategy & Tactics, The Napoleon … Continue reading

Early that night, as the temperature dropped almost to freezing and an icy rain began to fall, the young soldiers of Meunier’s command slept in huddled groups facing Heurtebise. A division made up of veteran units from Spain (although once again only at a strength of 1,900 men) under General of Division Pierre–Francois–Joseph Boyer, who had only recently been promoted (16th February 1814) and had formerly seen action as a cavalry commander, bivouacked around the village of Bouconville, in support of Meunier. These troops comprised the Young Guard 1st Corps under Marshal Ney. One brigade of the Old Guard camped near Craonne, with the other at Corbény (3,800 men), both under the command of General of Division Louis Friant. Out on the left the 2nd Imperial Guard cavalry division (1,350 men) under Rémi–Joseph–Isidore Exelmans was at Craonelle and Oulches. The 7th Young Guard division (3,800 men) under General of Division Joseph Boyer de Rébeval (Marshal Victors 2nd Young Guard Corps) bedded down for the night around Berry–au–Bac, together with the 6th Heavy Cavalry Division (2,200 men), commanded by General of Division Nicolas–Francois–Roussel d’Hurbal (part of the cavalry corps of General of Division Emmanuel de Grouchy), the 8th Young Guard Division under General of Division Henri–Franҫois–Marie Charpentier and 2nd Young Guard Division of General of Division Jean–Baptiste–Franҫois Curial ( 3,600 and 1,000 men respectively, both of Marshal Victors 2nd Young Guard Corps). The 1st Young Guard Cavalry Division of General of Division Louis–Marie–Lévesque de Lafériére (1,200 men) and the 1st Old Guard Cavalry Division (4,200 men) under General of Division Pierre–David Colbert de Chabanais (hereafter known as Colbert’s division), were encamped some two hundred meters to the rear of Berry–au–Bac. Marmont’s troops, around Braisne and Mortier’s around Cormicy were still south of the River Aisne. [44]Petre. F.Loraine, Napoleon at Bay, 1814, page 122. There is much confusion concerning the various infantry divisions and corps which constituted the French army during the 1814 campaign. Many … Continue reading

Napoleon himself spent the night in Corbeny. The mayor of the village of Beaurieux, Monsieur M. De Bussy, had been studying at the military school of Brienne when the French Emperor himself was a student there, and Napoleon now sent for him in order to familiarise himself with the local terrain. Thereafter he began to make his plans for the forthcoming battle and at 4.00 a.m. on the morning of the 7th March orders were issued for their implementation.

The veterans from Spain under P. Boyer and Meunier’s 1st Young Guard Division, both under Ney’s command, would attack the Russian left flank anchored on the village of Ailles. In the centre Marshal Victor’s corps would attack Heurtebise Farm, with Friant’s Old Guard and the army artillery reserve in support. The cavalry divisions under Exelmans and Colbert, under the overall command of General of Division Etienne–Marie–Antoine Champion de Nansouty, would move to turn the Russian right flank on the plateau near the village of Vassogne. The remainder of the army, Marshal Mortier’s Young and Middle Guard Divisions, were gathered around Berry–au–Bac ready to assist where required.Marshal Marmont’s corps, which was quite some distance away, was to move quickly to join the rest of the army. In all, the French forces available for immediate action numbered around 33,000 men with 150 cannon.

Before commencing with the details of the battle it is worth considering the quality of the French troops about to engage in one of Napoleon’s bloodiest battles. The late military historian, Dr Paddy Griffith, in his work, A Book of Sandhurst Wargames, gives a very good account of the type of young and lean recruits who heeded the call Allons z’enfants:

…it is worth looking at the action from the viewpoint of the French formation which bore the brunt of the fighting: the Second [Young] Guard Voltigeur Division of Marshal Victor’s army corps.

This formation could certainly boast an astonishing prestigious title, since Napoleon’s Imperial Guard was deeply feared by all who encountered it, and was widely believed to be the finest fighting force in Europe. Equally, the word “voltigeurs” [my inverted comers] itself normally signified a light infantryman of the most skilful type. A regiment’s voltigeurs were normally the élite soldiers of their unit, in company with their heavy infantry colleagues of the grenadiers. The Second Guard Voltigeur Division therefore had imposing precedents to live up to when it entered the field at Craonne.

Yet the remarkable fact is that the Second Guard Voltigeur Division had been in existence for little more than a month when it first underwent the ordeal of battle. It had been conceived by Napoleon only on 6th February 1814, while over three–quarters of its men were still complete civilians. By the 16th February, they had been issued with equipment of a sort (some men were even lucky enough to get greatcoats), and had been marshalled into some approximation of orderly units. They had been married up with their cadres of veteran soldiers, experienced NCOs and officers, all under the tough old warrior who commanded the division–General Boyer de Rébéval. [45]Griffith. Paddy, A Book of Sandhurts Wargames, page 25.

If the Imperial Guard had been reduced to such a state of improvisation one can only guess at what condition the rest of the army must have been in.

Riding out at 8.00 a.m. in the morning escorted by the duty squadron of the chasseur à cheval of the Imperial Guard, Napoleon reconnoitred the enemy position from the mill of Craonne. He could see the thick masses of Russian battalions covering the ground that dominated the Foulon valley, and further back he could discern still more enemy formations facing Ailles. The constricted ground where the plateau narrowed around the farm of Heurtebise was covered by the Russian artillery, while the farm itself had been strengthened. The roads were like an ice rink since it had rained then frozen hard during the night.

The French artillery positioned near the village of Oulches opened the battle at around 9.00 a.m., the Russian forward batteries bucking into action in response; the frosty air emphasising each discharge of the hostile cannons. Soon thick clouds of smoke began to billow across the landscape, the cold and windless temperature causing it to disperse only slowly. However, the distance proved too great for any real damage to occur on each side, the only detrimental effect being the fact that the hot headed Marshal Ney took the first salvoes as being the signal for him to commence his attack on the Russian left. Ney had received strict instructions to hold back his troops until such time as the French attack against the Russian centre had developed. Even so, with his usual total disregard for following orders, he sent P.Boyer’s veterans forward to take the village of Ailles, while Meunier’s weak division struggled to gain the plateau to the south–east of the village. This premature meant that Marshal Victor’s troops were still not properly concentrated for the assault on the Russian centre, the slippery condition of the roads slowing down the movements of troops and guns. [46]Petre. F.Loraine, Napoleon at Bay, 1814, page 125. Now, as they began to arrive, instead of mounting an attack on the Russian central gun line, Victor was forced to send Boyer de Rébéval division to assist Meunier’s troops over on the right, who had lost heavily and were on the point of falling back.

Boyer de Rébéval was instructed to advance up the road from the Abbey of Vauclerc, which was now full of wounded Russian and French, and take out Hurtebise Farm. The appearance of these fresh troops put new heart into Meunier’s weary soldiers and they soon rallied, while Boyer de Rébéval’s men pressed on and cleared the farm. Thereafter his division deployed into a line of small columns across the narrow neck of the plateau and advance on the Russian central massed formations of cannon and men. Unfortunately for general Boyer de Rébéval his supporting artillery was not handled properly, their fire doing little damage despite the efforts of its officers. [47]Griffith. Paddy, A Book of Sandhurst Wargames, page 28.To add to his woes, Marshal Victor, his corps commander, was wounded and forced to leave the field. Thus the division was stuck out on its own like the proverbial “sore thumb.”

Griffith’s states:

There are a number of telling comments in the sources which describe what happened next. One reads that ‘the fire of the [French] infantry had little effect since in this division the oldest soldier had less than 20 days of service.’ The Russians were far too strong for the French to make headway with an attack, and yet retreat seemed to be equally impossible since the men would probably lack the steadiness to make the necessary manoeuvres. ‘Flattened by grapeshot, Boyer de Rébéval did not dare to make the least movement to shelter his conscripts for fear of seeing them dispersed in flight.’

It was a dilemma from which no happy solution could emerge, and it seemed to continue for a horribly long time. One survivor claiming that they stood in line for three hours, but this is probably an exaggeration. Another participant was probably nearer the mark when he said, ‘for a whole hour we were massacred in the most fearful manner.’ One account says that the soldiers were ‘scythed down like a field of corn.’ Another talks of them ‘melting like snow.’

After the battle, the division which had started from Paris with nearly 8,000 effectives was left with only 1,686 officers and men. It was promptly re–classified as a brigade. There were 1,708 battle casualties in the division, including both brigadiers and Boyer de Rébéval himself. He suffered a bullet contusion on his left leg and a piece of grapeshot in his chest. His horse was also hit, which brought to 20 the number he had lost in the course of his military career. [48]Griffith. Paddy, A Book of Sandhurst Wargames, page 28.

Over on the French left Nansouty had been unable to find a suitable route onto the plateau for his cavalry, finally having to move about a half mile further out than anticipated until he at last found a steep road that led to the spur above Vassogne.

Napoleon, having issued his orders, could do no more now than await the fulfilment of his plans, but like everything else in war, these did not take into account the improbable and the imponderable. By 1.00 p.m. with Ney’s troops on the right struggling to gain the high ground and Boyer de Rébéval’s division stalled in the centre, it was decided to try to get in among the Russian gun line by using cavalry. These troops consisted of a brigade of dragoons from Roussel d’Hurbal’s division commanded by General of Brigade Louis–Ernst–Joseph Sparre. Things did not go well from the start. As the brigade advanced it failed to fan out sufficiently and received severe punishment from the Russian artillery. When it finally managed to get itself sorted out Sparre was wounded, closely followed by Grouchy who had accompanied the attack. The dragoons faltered and seeing that their impetus was lost Vorontsov ordered a counter–attack which drove the dragoons back in total disarray, scattering their own infantry and forcing them back off the plateau and down into the wood of Vauclerc where they caused Ney’s young recruits to break back in their turn, ‘…few members of either group could be collected before nightfall.’ [49]Griffith. Paddy, A Book of Sandhurst Wargames, page 28.

At last, over on the French left flank, Nansouty had finally managed to get his troopers up onto the plateau. His squadrons formed up on the spur of ground between the villages of Paissy and Vassogne. Here they routed the detachments of Cossacks and hussars covering Vorontzov’s right flank and defeated two battalions of Russian infantry sent to their support. It was at this stage of the battle (around 1.45 p.m.), having been informed of the mauling that Ney’s and Boyer de Rébéval’s troops were receiving over on the French right, Napoleon called for the cavalry of the Old Guard to restore the situation. The horse grenadiers and chasseurs, led by Laferriére, came cantering across the plateau from the Craonne mill, past Heurtebise Farm, gathering speed until they hit the Russian gun line, leaving a trail of mangled men and horses in their wake. Laferriére crashed to the ground, his leg taken off by a shell while the now badly mixed up squadrons milled around the Russian cannons, slashing and stabbing the gun crews, many of whom had taken refuge beneath their guns. With their sword arms tiring and their horses blown the guard cavalry were finally driven back by the concentrated volleys of the Russian massed battalions. Their sacrifice had not been in vain, as the time gained allowed Marshal Victor to bring up Charpentier’s division, which at 2.30 p.m. had advanced along the southern slopes and attacked the woods of Bois de Quatre Heures, which could not be covered by Russian cannon. Storming into the wood they cleared out the defenders with ease, finally linking up with Nansouty’s cavalry, both now moving to attack the Russian right flank. [50]Petre. F.Loraine, Napoleon at Bay, 1814, page 127.

Under the cover of Laferriére’s cavalry attack General of Division Antoine Drouot, Chief of the Artillery of the Imperial Guard, brought forward 72 guns of the Guard artillery, including the heavy 12 pounders known by the soldiers as “Napoleon’s Beautiful Daughters,”, placing them in line about 300 meters in front of Heurtebise Farm. Here they began to smother the Russian position with a hail of metal.

Blücher had been worried for some time by not seeing any signs of Winzingerode’s cavalry turning movement over on the French right, not knowing that because of the roughness of the terrain and the slippery roads, it had been caught up in an enormous traffic jam to the north–west of the Ailette River. At around 1.30 p.m. he had sent Sacken orders to pull back to the west so that the whole army could be concentrated on the Laon plateau. However, Vorontzov, who was in command of the Russian formations directly in contact with the French demurred, stated that he had already withdrawn a considerable distance from his original position, and saw no point in yielding any more ground, particularly in view of the French cavalry poised to strike at the first signs of any retrograde movements. Only a direct order from Sacken, coupled with Drouot’s guns ploughing bloody lanes through the ranks of his infantry, caused him to concur and he began to draw back his battalions by leap–frogging each one past the other. [51]Griffith. Paddy, A Book of Sandhurst Wargames, page 29.

By 3.00 p.m. Napoleon had been informed that a considerable body of enemy cavalry were approaching from the direction of Chamouille to threaten the French right flank. With what remained of Ney’s formations still in a condition to fight once more up on the plateau, the Emperor ordered all of the reserve artillery, together with the still serviceable cannon of Victor’s corps, to join Drouot’s Guard artillery. While the guns were moving forward P. Boyer finally managed to capture the village of Ailles, which was burning furiously, the Russian defenders falling back up the steep sides of the plateau.