The Battle of Austerlitz, 2nd December 1805

Introduction

The following article is not meant to be a complete history of the 1805 campaign but does seek to show in some detail how both sides manoeuvred on the battlefield and the formations adopted by each as the battle progressed. The maps are all taken from Dr Christopher Duff’s excellent work, Austerlitz 1805, and although I have sought to acquire permission to use said maps I have been unable to contact Dr Duffy and gain his consent to use them. His publishers have informed me that they do not hold any copyright on the maps, which remain in the sole possession of Dr Duffy who, incidently, drew them all himself. The diagrams of the various French formations adapted during the battle used herewith are also subject to the same problem, therefore if any infringement has been made I will be only too happy to rectify the situation. All maps taken from the book and used herewith have been fully credited to Dr Duffy, ditto Nosworthy.

This article was written so that the reader can follow the battle on Dr Bob’s panoramas. It is not meant to be a detailed account of all that took place during the action, and therefore in writing it I have drawn heavily on just two or three main sources cherry- picking the best accounts I thought applicable.

See here for full interactive panoramas with maps.

New Strategy

Austerlitz was Napoleon’s greatest victory. The campaign and battle show how he had continued to improve and develop on a style of strategy first tested in Italy in 1796 and again in 1800: indeed the nucleus of the 1805 campaign were formulated in 1800 when Napoleon had worked out a plan to attack the Austrian forces in South Germany using troops he had gathered at Dijon and, in conjunction with general Moreau’s army, envelop the enemy by a movement through Switzerland doing the greatest damage to their army as possible before marching on Vienna. Unfortunately the plan was not put into action since Moreau refused to subordinate himself to Napoleon. In 1805 he struck at the Austrians under Mack, who were between Munich and Ulm, by moving on a wide front, enveloping them by sending Marshal Bernadotte marching from Hanover through the Principality of Ansbach, violating Prussian neutrality. At Austerlitz Napoleon also showed his ability to apply the defensive – offensive strategy to best effect, which entails fine judgement and timing in knowing when to pass from one to the other at just the right moment. As the German military historian Hans Delbrück states:

Of all types of battle, the defensive – offensive battle is the most effective. Both defence and offence have their advantages and weaknesses. The principle advantage of the defensive is the choice of the battlefield and the full exploitation of the terrain and firearms. The principle advantage of the offensive is the morale lift of the attack, the choice of the point of attack, and the positive outcome. The defensive initially always brings only a negative outcome. Consequently, purely defensive battles are only very seldom won (Crécy, 1346; Omdurman, 1898). The greatest result, however, is achieved when the commander goes over to the counter attack from a good defensive at the right moment and in the right place. We have become familiar with Marathon as a classical example of the defensive/offensive battle. Austerlitz is the modern counterpart of that battle. This battle is important for us in both its plan and execution because it shows us a commander in complete self-control, because we see here how this man with all his daring still never lost his presence of mind. [1]Delbrück. Hans, The Dawn of Modern Warfare, page 434 – 435.

The French Army.

Infantry

For many years it became an accepted fact by armchair theorists that the French Napoleonic armies fought almost all their battles by first softening up the opposition with massed artillery fire and then sending in the infantry formed in huge columns of attack to bulldozer their way through enemy linear formations, thereafter the cavalry went forward to complete the victory. While much of this was true during his later campaigns, these tactics were far from the norm during the two years of Napoleon’s greatest triumphs,1805 and 1806. Having said that, and accepting Napoleon’s undoubted talents as a military commander, one must nevertheless look at the army he inherited when he became Emperor of the French in 1804.

For thirteen years before he came to the throne the Revolutionary armies of France had been developing into highly motivated and competent fighting units, able to adapt, change and develop tactical skills that were suited to the mass notion of a Nation in Arms. The old army of the Ancien Régime had ceased to exist as a real fighting force after the mutinies of 1789. Most of its experienced officers had emigrated and as chaos and disorder continued over 6,000 left the army between July 1791 and the end of 1792. Despite all this the Committee of Public Safety took control of the government and the Republican Constitution of the Year I (June 24th 1793) declared that all Frenchmen would be soldiers, thus creating The Nation in Arms. [2]Rothenberg. Gunther E, The Art of Warfare in the Napoleonic Age, page 98 – 100.

The levee en masse produced, after a stumbling start, a military machine that could fight as skirmishers and be relied upon to return to their original formations, albeit sometimes in their own time. These ragamuffins could also feed themselves off the land, which in turn allowed them a far more rapid movement rate than the supply train and magazine bound armies of the other nations of Europe.

The old royal armies of France had, on occasion, used Jean Charles, Chevalier Folard’s (1669-1752) idea of sudden shock attacks using columns of infantry linked by infantry in line, Marshal de Saxe using this method to good effect at the battle of Roucoux in 1746. But although Folard’s system was taken on board and incorporated in the French drill-books of the mid-eighteenth century, it remained a controversial issue between advocates of l’ordre mince (line), and those in favour of the more aggressive l’ordre profond (column). [3]Glover. Michael, Warfare of the Age of Bonaparte, page 14-15. Also, during the turmoil of the first years of the new republic, the tactical flexibility put forward by Hyppolyte de Guibert (1743-1790) in his work, Essai général de tactique, were attempted. These were devised so that a change from line into column and back either to the front or to a flank could be carried out rapidly. However, it took time to teach the new recruits these tactics and consequently where a commander had regular troops he would use them in line formation, when commanding new levies column was used. [4]Ibid, page 16. What we find during the battle of Austerlitz are cases of French corps and divisional commanders using both systems of line and column in conjunction with each other, but sometimes at variance to set instructions formulated for their use prior to the engagement.

French Napoleonic infantry regiments were made up of three or four battalions of six companies each, with two of these companies being designated as one votigeurs and one grenadier. At full establishment each regiment would be between 3000 and 3,400, but at Austerlitz these numbers had been eroded to around 2,000- 1,600 men per regiment.

Cavalry

The French cavalry suffered a decline in both trained troopers and schooled horses after the upheavals of the revolution and many of the old royal regiments either disappeared or had their titles changed. In turn many cavalry officers who remained in the service came from old noble families, Jean-Joseph-Ange d’Hautpoul and Etienne-Marie-Antoine-Champion de Nansouty being two of the most famous who threw in their lot with Napoleon. Rank and title gave way to talent and many of the great cavalry commanders of the Empire came from lowly stations: Joachim Murat was the son of a innkeeper, Frederic-Louis-Henri Walther’s father was a pastor and Edouard-Jean-Baptise Milhaud was a farmer’s son, all had one thing in common, ‘the coup d’oeil and enterprise of the French colonels and generals, who threw their depleted regiments with terrible effect against the flanks and rear of the allied cavalry.’ [5]Duffy. Christopher, Austerlitz 1805, page 17.

Cavalry tactics had also gone through a period of change. Originally the mounted arm of an army were normally deployed on the flanks during a battle and therefore when called into action engaged their counterparts in the opposing army in a purely cavalry against cavalry engagement. During the Seven Years War it became the practice to form cavalry as a second line, behind the infantry. It was not expected to attack enemy infantry that were in good order and whose moral was steady. Only when the enemy formations showed signs of disorder, or when they could be caught while attempting a manoeuvre would the cavalry be let loose, mainly in two compact lines delivering two successive shocks. The cavalry charge began, normally, at around 200-300 meters from the target of attack and the command ‘Escadrons, en avant-marche!’ would be given and the regiment would begin to advance at the walk; after about 50 meters the order ‘Au trot!’ rang out and then this pace was continued until 100-150 meters was reached upon which the order ‘Au galop!’ was given. This pace was continued until at around 60 meters from the enemy the final command ‘Chargez!’ was given, hurling horse and rider into the Full or Triple Gallop. If the timing was right and the horses were not blown, plus the lines still being in good order, the impact of two successive waves of horsemen could be quite devastating against infantry in either linear formation or already shaken by artillery fire. In engagements of cavalry against cavalry similar tactics were used but normally after the initial shock and impact both sides lost all coherence and became a mass of sabre slashing individual combats. [6]Johnson.David, Napoleon’s Cavalry and its Leaders, page 34-35. See also Noseworthy. Brent, The Battle Tactics of Napoleon And His Enemies, Part 1V, page 263- 357. Moreover, as will be seen at Austerlitz, the French and Allied cavalry, also adapted various tactical formations such as column and line, the feint attack against an enemy square, and other manoeuvres requiring skill and dexterity. [7]Noseworthy. Brent, Battle Tactics of Napoleon And His Enemies, page 336-337.

At Austerlitz the French cavalry regiments all had four squadrons and came in three categories of heavy, medium and light. The real “heavies” were made up of nine cuirassiers and two carabinier regiments of four squadrons each with, allowing for natural wastage on campaign, around between 90-120 troopers per squadron. The medium cavalry were dragoons. Although not carrying the body armour of the cuirassiers (the carabineres also did not wear armour until 1809), and who during the early years of the Napoleonic wars sometimes fought on foot owing to the lack of trained horses, were nevertheless on occasion lumped together with the heavy units to bolster the strength of the reserve cavalry corps.

The light cavalry consisted of Hussar and Chasseur-à-Cheval regiments whose principle tasks were reconnaissance and scouting, but who would also be used to charge enemy units at an opportune moment when the situation dictated. Divisions and brigades of light cavalry were attached to each army corps as well as being used independently.

Artillery

The French artillery was not drastically changed by the events of 1789. The old Royal Artillerie was a highly respected arm of the service and the victories at the battle of Valmy and Jemappe in 1792 and at Wattignies in 1793, where the French artillery played vital roles, discouraged any tampering or meddling with its basic formation and efficiency. [8]Rogers. Col. H.C.B., Napoleon’s Army, page 74.

The cannons came in six main weight of shot categories and dimensions for field artillery, 4 pounders, 8 pounders, and 12 pounders, together with 6 and 8 inch howitzers. Although a new 6 pounder field gun had been developed not many of these were in use in 1805. These guns were all constructed using the standardized calibres and weight reduced carriages and limbers introduced by Count Jean-Baptiste de Gribeauval in 1765.

Guns were organized into batteries of foot and horse artillery, the latter being mainly used by the various cavalry brigades and divisions for swifter deployment. Each battery comprised of 6 field guns and 2 howitzers.

The Austrian Army

Infantry

After the capitulation at Ulm the Austrian forces actually on the field of Austerlitz was less than 17,000 men. Of these the infantry numbered 11,420 cavalry; 3,195, artillery; 1,775 and pioneers 430, together with 70 pieces of artillery. [9]Castle. Ian, Austerlitz. Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe, page 222.

The master of the disaster at Ulm (20th October 1805), Lieutenant-General Carl Baron Mack von Leiberich, had been brought back out of retirement to become Quartermaster General (Chief of Staff) of the army in April 1805, which eventually led to the Archduke Charles, Austria’s best field commander and younger brother of the Emperor Francis II, being relegated to no more than nominal minister of war. Upon sitting in at one of Mack’s lectures on how he meant to change the old Austrian method of cumbersome supply trains and adopt a system of living off the land similar to the French, the Archduke Charles remarked that, ‘This man is perfectly crazy!’ The cabinet minister, Ludwig Coblenzl, who had been one of the instigators in bringing Mack out of retirement to take command of the army, replied by saying, ‘Ah well – he is useful, and that is enough!’ [10]M. Angeli, Erzherzor Carl, Vienna 1897. Quoted in, Duffy, page 25.

Mack’s attempts at structural changes in the Austrian army only began a few weeks before the commencement of the hostilities in 1805 and caused so much discontent within the army that many of the senior officers never even attempted to put them into practice and even those that did expressed doubts concerning their viability.

The normal strength of an infantry regiment was three field battalions, two grenadier companies and one depot battalion, together with two 6pdr field guns. Mack ‘s reforms reduced the number of companies in each battalion from six down to four with the extra companies forming new battalions. The first battalion was termed as “velite grenadiers” and were joined with the original two grenadier companies thus forming a grenadier battalion. The other surplus companies of the original second and third battalions were used to form a forth battalion. The support artillery was increased to six 6pdr guns.

The border regiments, or Grenz Regiments, also went through similar changes with each regiment having three 3pdr guns. [11]Johnson. Ray, Napoleonic Armies: A Wargamer’s Campaign Directory 1805 – 1815, page 87.

Cavalry

Austrian cavalry was made up of eight regiments of cuirassiers, six regiments of dragoons, six regiments of chevaulégers (light dragoons), three regiments of hussars and three of lancers. Each regiment had eight squadrons of varying complements, depending on the type of cavalry, which gave around 1,400 troopers for the cuirassier and dragoon regiments and 1,700 for the others. These units were not touched by Mack’s reforms. [12]Duffy. Christopher, Austerlitz 1805, page 27.

Tactics were similar to those of the French but they also adopted Frederick the Great’s ‘secret’ cavalry column of attack, which consisted of having several squadrons of cavalry in closed column, riding boot to boot, with more cavalry coming on behind in additional lines. Although being effective on occasion, it could be defeated by an enemy cavalry flanking attack. [13]Noseworthy. Brent, Battle Tactics of Napoleon and his Enemies, page 269.

Artillery

In 1805 Austrian artillery still had its head firmly buried in the eighteenth century with such a low establishment that line infantry had to be used as labourers to drag and move guns around on campaign. As if this were not bad enough, the horse artillery did not even have a permanent establishment, but had to be created when war was declared.

The guns came in four calibres; 3 pounders, 6 pounders, 12 pounders, and a 7 pounder howitzer. Unlike the French who concentrated their batteries on the battlefield, the Austrian light artillery was parcelled out among the infantry battalions and the 12 pounders grouped in batteries kept in reserve. [14]Duffy. Christopher, Austerlitz 1805, page 27-28.

The Russian Army

Infantry

On paper the Russian forces were formidable with almost 300,000 regulars and over 100,000 cossacks. These, together with recruits and subsidiary units, came to more than 500,000. The main problem with the army, at least until Alexander I came to the throne, was that his father, Tsar Paul I, had been obsessed by the Prussian army of Frederick the Great. This obsession had caused a retrograde step backwards both in military drill, tactics and uniform, to such an extent that, …’in almost every respect the Russian army was set back by half a century. [15]Duffy. Christopher, Austerlitz 1805, page 30.

When becoming Tsar in 1801 Alexander began reforming the army by setting up a Ministry of Land Forces and a Military Reform Commission but progress was slow owing to many of the older generals being reluctant to change, while the younger officer class gradually managed to draw Alexander, with his partiality towards grand schemes and plans, into their circle of influence. Buxhöwden, one of the older and uncompromising Russian commanders at Austerlitz, wrote:

‘But at the present time authority has declined to such an extent that everyone from ensign to general treats one another with the same familiarity. A sentiment of indifference and disrespect has insinuated itself in the relations between subordinate and commander, and we have forgotten the awe which is indispensable among military men.’ [16]Ibid, page 31.

Even with the reforms tentatively taking place the Russian infantry of 1805 still clung to tactics set down in the Military Code Concerning the Field Service of Infantry (1796) and the Tactical Rules for Military Evolutions (1797). These taught Prussian linear formations for the infantry in three ranks marching without bending the knee, having the foot brought down sharply with each step. Platoon fire was delivered in three ranks with each battalion platoon firing rolling volleys in succession. [17]Duffy, page 33. See also Rothenberg. Gunther E, The Art of Warfare in the Age of Napoleon, page 196-201. The 1968 Russian epic, War and Peace directed by Sergei Bondarchuck shows in great detail how … Continue reading

Almost all Russian infantry regiments had three battalions and each battalion was made up of four companies of two platoons each. A line battalion at full strength numbered 738 officers and men, while the Guard battalions numbered 764 each, with the exception of the Preobrazhensk Regiment which had four. [18]Johnson. Ray, Napoleonic Armies, page 105-106. Thanks to the almost god like reverence given to General A.V.Suvorov (1729 – 1800) many of the Russian senior officers followed his dictum that, ‘ The bullet is a stupid bitch and the bayonet a fine fellow,’ this causing the reliance on cold steel seen as being far more effective than musketry drill.

The Cavalry

Tsar Paul had also set down his own ideas in regard to cavalry tactics in his 1796, Code of Field Cavalry Service. Although Alexander had instigated reforms for the cavalry when he became Emperor only a general reorganisation in the size of the various regiments was carried out. The heavy cuirassier regiments were reduced to six, with each regiment fielding five squadrons of 150 men each; dragoon regiments were increased to twenty two, each regiment having five squadrons of 150 men; hussar regiment numbered nine, each with five squadrons, each squadron had 120 men; uhlan regiments originally numbered four but Alexander had converted a dragoon regiment into the Grand Duke Constantine Uhlans, these however did not carry the lance at Austerlitz.

Russian cavalry, as well as their counterparts in other Western European armies at this time, adopted the line formation allowing the maximum amount of swords and sabres to be brought against the enemy; the linear formation also allowed a larger cavalry grouping to outflank smaller units.

The Echelon formation was also used by other European cavalry commanders but, as we shall see, Russian mounted tactics sometimes went sadly awry.

The cossacks were good irregular cavalry who, with the exception of the Guard Cossack Regiment, tended to shy away from a full blown engagement with well formed infantry and cavalry. Their main form of attack was against a flank or in getting among a broken formation of enemy units and causing as much damage as possible with their lances, a weapon with which they were particularly adept in the use of. [19]See Nosworthy, page 301-302.

Artillery

Ever since their giant and far seeing Tsar, Peter the Great, had ordered church bells to be melted down and turned into cannons, the Russian army always went to war with a formidable array artillery. The reforms of General Arakcheev had introduced lighter gun carriages and caissons in line with the French Gribeauval system, and his development of 6 pounder and 12 pounder cannon, in both light and medium versions, together with 3-, 10- and 20 pounder unicorns howitzers ( a name taken from the design of their lifting handles), should have given the Russians a considerable advantage on the field of Austerlitz; that this never occurred, ‘…is representative of the Russian army as a whole, where the value of men and material was nullified by a lack of ensemble.’

Austerlitz. The French Plans in Brief

When Napoleon arose and mounted his horse for a reconnaissance of the battlefield at dawn on the 1st of December he was somewhat perplexed not to find the Austro-Russian army, as he had expected, advancing towards the Pratzen Plateau, which he had left undefended in the hope that the allies would assume that the French intended to retreat. Therefore he had originally worked out a plan that involved drawing the allies into attacking his right centre, after which he would entrap them on either side with Davout’s corps coming up from the south; however, since it was now becoming apparent that Davout would only be able to reach the field with a worn down and depleted remnant of his III Corps, in consequence Napoleon changed his plan after returning to camp, and during the evening, in what became the Dispositions Générals, dictated these, plus various verbal instructions. Now Davout was ordered to drive away any allied units that may have reached the area Gross-Raigern and Turas on the left of the Goldbach stream and thereafter join with Soult’s IV Corps on the French right flank. The main group of the army would then advance against the allies, once they had descended from the Pratzen plateau, in an oblique attack, right wing leading. This meant that, if Napoleon’s calculations were correct, Soult’s infantry would move swiftly and take the denuded Pratzen heights while the rest of the army wheeled in a clockwise direction cutting off the allied line of communications and hitting them in flank and rear. [20]Duffy, page 88-89

Allied Plans

“The best laid schemes o’mice an men

Gang aft a-gley.” [21]Robert Burns, Poem to a Mouse 1786

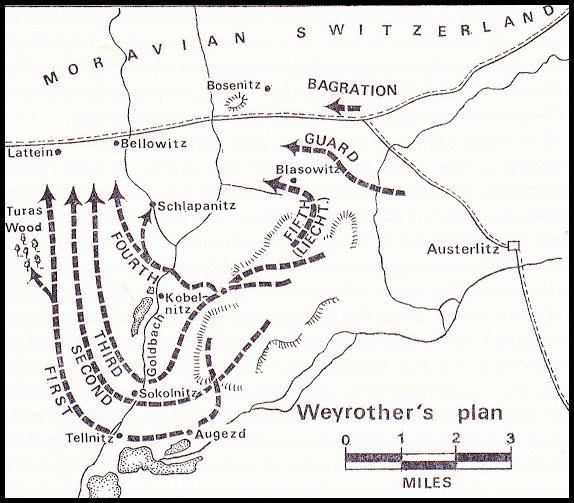

The Allied plan for defeating Napoleon was drawn up by Austrian chief-of-staff Major General Franz von Weyrother, and although Duffy states that it would gain high marks as an operational order in a modern military academy, it was totally unsuitable to the actual situation, not only of the terrain, but also to the considered dispositions of the enemy, as well as the unwieldy formations designated to carry out the task.

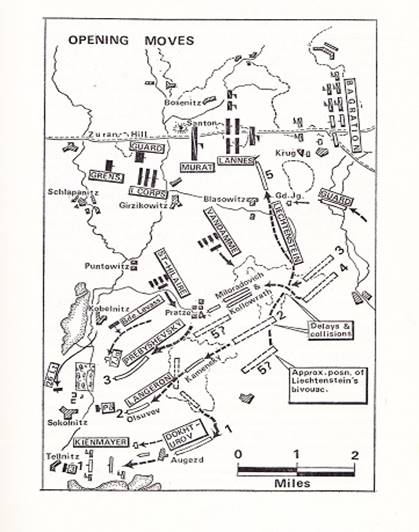

The plan called for five columns, with General Freidrich von Buxhöwden taking command of three of these and moving down from the Prazen heights and manoeuvring south against the French right wing, then turning north and rolling up the enemy line; the other two columns under Generals Kollowrath and Miloradovich would cross the Goldbach stream to the north of the village of Kobelnitz hitting the (supposed) enemy as it reeled back from Buxhöwden’s flanking attack. The remainder of the allied army would support these operations: a column consisting of Austrian and Russian cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant-General Johann Liechtenstein, would forstall any attempt by the French cavalry from attacking their infantry formations by taking ground around the village of Blasowitz, while further back on Liechtenstien’s right the Russian Imperial Guard under Grand Duke Constantine (the Tsar’s brother) would deploy in reserve between Balsowitz and Krug. Further to the right again Lieutenant-General P.I.Bagration was to remain on the defensive covering the Brünn-Olmütz highway until such time that he observed the advance of the allied left wing driving back the enemy when he should use his own judgement and fall on and crush the French left wing. The field commander of the allied forces was given to General-in-Chief Golenishchev-Kutuzov, and although much has been written about his personal opinions and doubts concerning Weyrother’s plan,, Tsar Alexander’s preference for the scheme made Kutuzov a commander without teeth. [22]For a more detailed account of French and Allied order-of-battle formations see Appendix A.

The Fog of Austerlitz

The Austrian Major-General Stutterheim supplies what is possibly the best account from the allied perspective. He commanded a brigade of cavalry in Lieutenant-General Kienmayer’s advance guard of the first column. His description of what occurred in the early hours of the morning on the 2nd December are a damming indictment of the way in which the allies were prepared to do battle against one of the finest commanders in the history of warfare, at the head of possibly the best army in Europe at that time. He states:

The dispositions for the attack of the French army was delivered to the general officers of the Austo-Russian army, soon after midnight, on the morning of the 2nd December. But the imperfect knowledge that was possessed of their position, although scarcely out of range of the enemy’s musketry, naturally made the suppositions upon which the disposition of the attack was founded also very indefinite. [23]Stutterheim. A Detailed Account of the Battle of Austerlitz, page 68.

It was in fact at around 1:00 am in the morning before all the general officers, with the exception of Bagration, were gathered together at Krzenowitz to receive their orders for battle. Weyrother then commenced to unfold a large map of the surrounding area on a table and began to explain his plans in great detail. As Langeron tells us:

‘He then read us the arrangements in a raised voice and with a conceited air which was designed to show us his deep-seated belief in his own merit and in our inability. He resembled a high school master reading a lesson to some young school children: we were perhaps likely schoolboys but he was far from being a good teacher. Kutuzov, seated and half asleep since we arrived at place, eventually did fall asleep completely before we left. Buxhöwden, standing, was listening and certainly understood nothing. Milioradovich kept quiet, Prebyshevsky kept in the background, and only Dokhturov examined the map with any attention. [24]Duffy, page 95.

Weyrother explained his plans in German and therefore had to pause every now and then to allow Major Toll to translate what he had said into Russian. [25]Since at this time French was the language of the court in almost all countries in Europe, one wonders why German was used. Maybe if both Emperors, Alexander and Francis, had been present at the … Continue reading As if this was not bad enough, after the meeting broke up, Toll had to write down translations in Russian for adjutants to deliver to the other Russian generals in the various columns so that they were themselves aware of what was intended. It was almost 3:00 am when Toll commenced this task and therefore the first shots of the battle had already been fired before some generals received their copies. [26]Duffy, page 97-98.

While the allied forces were awaiting instructions under a freezing night sky, across the Goldbach stream, also huddled around their campfires against the cold, the French were also waiting, but in their case they were only wating for the enemy to show his hand. As the first grey light of dawn began to show in the eastern sky, Napoleon was with his marshals on the Zuran Hill to issue them their final instructions. Timing was of the essence and the Emperor took special care in making sure that Soult in particular understood exactly when and how his attack was to develop. Marshal Davout, who had now joined the main army, despite elements of his own corps still being some distance away, was instructed to move to support General Legrand, bolstering up the French right flank.

Before first light, at around 6:30 am, the advance guard of the allied First Column commanded by Kienmayer began moving slowly forward from Augezd towards Tellnitz, the 1st Szeckel-Grenz Regiment leading the way. The Grenz infantry were recruited from along the military frontier between Austria and Turkey and were good at fieldcraft and marksmanship, however, they were not used correctly at Austerliz and were sent into the attack in the same tight formations as the regular line infantry. Kienmayer himself, although knowing that his task was to seize and hold Tellnitz thus opening a way for the first column of the allied army, and being aware that both French cavalry and infantry were ensconced in and around the village, sent a small detachment of cavalry to towards Menitz on his left and the Hessen-Homburg Hussar Regiment together with the 11th Széckel Hussars to the right. The 2nd Széckel Grenz Regiment and one battalion of the 7th Brod Grenz Regiment (Slavonia) he held in reserve. The first attack on Tellnitz was therefore made only by the 1st Széckel Grenz Regiment, some 600 strong, commanded by Colonel Knesevich, a force far too weak and in a formation that made a perfect target for the awaiting French. [27]Castle. Ian, Austerlitz. Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe page148.

Tellnitz was defended by 2,500 infantry and around 1,000 cavalry. The infantry comprised two foreign battalions, one from Corsica, the Tiraillers Corse, the other from Italy, the Tiraillers du Po, both battalions weakened by their exertions during the campaign, and mustering only 900 between them. The 3rd Line Infantry Regiment made up the bulk of the defending troops actually stationed within the houses and grounds of the Tellnitz itself, although the tirailleur companies were thrown forward along the crest of the rising ground in front of village itself, with the Corse amd Pô contingents holding the vineyards around to the north. The cavalry under General Margaron were on the right of the village.

Instead of using the skills of the Grenz troops to best effect by engaging the French skirmish line in a duel of light tactics for which they were well adapted, Knesevich pushed them forward shoulder to shoulder in linear formation which caused heavy casualties and forced the 1st battalion of the Szeckel to fall back. Upon viewing this setback, Kienmayer sent the 2nd battalion forward to join them in a fresh assault on the high ground in front of Tellnitz. Once again advancing in linear formation the two battalions were swept back with heavy losses, carpeting the ground with dead and twitching bodies. Since the whole Allied plan revolved around the 1st Column securing a crossing of the Goldbach stream, Kienmayer now ordered Major-General Stutterheim to press the assault. Gathering the now much depleted and shaken Szeckels together, Stutterheim once more led them forward and this time managed to drive back the French skirmish line, these falling back and either taking up positions behind barricades in the streets of Tellnitz, or along the Goldbach covering Sokolnitz village. [28]Castle, page 148. Stutterheim, page 84.

The mist having lifted a little, together with daylight now strengthening, Kienmayer, seeing that Tellnitz was well defended, rather than using the twelve pieces of artillery that he had to batter the village, once more sent in infantry assaults, this time ordering General Carneville to support the 1st Szeckel regiment with the two battalions of the 2nd Szeckel and the one battalion of the Brod (Croat) Grenzregiment. Perhaps five attacks were made during the course of an hour to try and take the village, which finally fell when Buxhöwden sent a battalion of the 7th Jäger and three battalions of the New Ingermanland Musketeer Regiment in to aid their hard pressed allies. This fresh injection of manpower soon settled the matter, and the 3rd Line were finally forced out of the village.

It was now about 8:00 am., and the sky was clearing. To the north, around Kobelnitz, General Legrand, commanding Soult’s right division, became concerned about the firing that had broken out around Tellnitz, and decided to see for himself what the situation was. Ordering the 26th Light Infantry Regiment to accompany him Legrand rode south towards Sokolniz where he suddenly became aware of masses of Russians pouring down the slopes of the Pratzen heights. These troops were the first brigade of Langaron’s 2nd Column and more were coming on through the now rapidly shredding veil of fog. At once perceiving the gravity of the situation Legrand threw out the first battalion of the 26th in skirmish order to aid the weak battalion of the Tirailleurs du Pô, the only French unit on this part of the field. The second battalion of the 26th, coming on behind were drawn up in and around Sokolnitz and its castle. [29]Duffy, page 105. The 1,800 French ensconced in and around Sokolnitz were now assailed by some 8,000 Allies, as Generals Langeron and Prebyshevsky, backed up by 30 cannon, came on in overwhelming force. By 8:30 am the village had been cleared but down at Tellnitz the situation was again placed in the balance.

Despite Tellnitz being in Allied hands after their bloody sacrifice to obtain it, things were far from settled as far as the French were concerned. Moving though the dark and fog Davout’s footsore and depleted forces under General’s Friant (infantry)and Bourcier (Dragoons) had set out from Gross-Raygern marching, as per instructions, towards Sokolnitz. At around 8:50 am Davout received a message from General Margaron who commanded the light cavalry screen between Tellnitz and Sokolnitz asking for support for the 3rd Line Regiment, which had been forced out of the former village by superior numbers. Immediately the bald and short sighted Marshal, at least the equal to Napoleon in making on the spot decisions in crucial situations, ordered the 1st Dragoon Regiment together with Heudelet’s infantry brigade to Tellnitz. At 9:00 am the 15th Light Infantry Regiment and the 108th Line Infantry Regiment, Heudelet leading, entered the village with drums beating and colours flying, driving the startled defenders out and into the ranks of the New Ingermanland Regiment which was coming forward in support, causing the whole mass to fall back in confusion. Things were once more turned around when, as the French 108th Line Regiment began to exploit their success by pushing on outside the village, the Hessen-Homburg Hussars, who had been placed in reserve, charged into their ranks slashing left and right and driving them back in their turn. In attempting to escape the sabre wielding Austrian cavalry, the survivors of the 108th fell back north only to come under a withering musket fire from their comrades in the 26th Light, who had been evicted from Sokolnitz and, amid smoke and the mist that still hung along the Goldbach stream, mistook them for the enemy. The situation was only stabilised when Captain Livadot of the 108th raised one of the regimental eagle standards. While Kienmayer consolidated his hold on Tellnitz, the overall commander of the left wing, General Buxhöwden, was now content to halt and await the progress of the 2nd and 3rd Allied Columns. [30]Duffy, page 110.

At Solkolnitz, at around 9:00 am, the two other brigades of Friant’s division, those of General Kister and Lochet, were drawn up to the west of the village; like their brethren in Heudelet’s brigade, they were well down in numbers after their leg shattering march from Vienna. Regardless of fatigue and empty stomachs, Friant sent Lochet’s brigade against the village, the 48th Line Infantry Regiment leading, the shock and determination of their attack driving the Russian defenders back. Coming on in support of the 48th the 111th Line Infantry Regiment also swept into the village, driving back a mass of mixed Russian infantry who were advancing leaderless and without cohesion. While Lochet’s troops cleared Sokolnitz, Kister’s brigade took post on the rising ground to the north of the village, in reserve. It did not take long for Langaron to bring forward fresh troops, in the form of the Perm Regiment and a battalion of the Kursk Regiment, to retake the village, driving back the 111th and trapping the 48th in the great storage barns and cottages in the south of the village. The fighting was severe, and now Friant sent Kister’s brigade back into the north-west of the village, his two regiments, 15th Light and 33rd Line occupied the ground inside the pheasantry and castle. As Langaron was preparing another counter attack to evict the defenders from Sokolnitz he received the shocking news that the French were actually advancing onto the Pratzen plateau. At first treating this information as mistaken identity, and that the troops were in fact Austrian, Langaron was soon made well aware of the gravity of the situation when another courier arrived with a message from Major-General Kamensky, commanding Langaron’s second brigade, stating the French were on the heights, and that he had turned his brigade to confront them, but was opposed by heavy enemy masses. [31]Castle, page 158-159.

We now leave the battle in the south and turn our attention to events on the Pratzen plateau. However, before continuing it is worth pausing for a moment to consider the dispositions and formations used by both sides during the fighting in and around Tellnitz and Sokolnitz.

Not much information is forthcoming with regard to just how street and house fighting was carried out, but it is fairly safe to say that, with the exception of modern weapons and robotics, most close quarter engagements in constricted village and town fighting remained the same right up until the twentieth century. Even today, combating guerilla and terrorist groups in heavily built up areas still entails house to house enter and eradicate tactics. There are so many instances of town and village combat during the Napoleonic Wars that one is surprised by the lack of information in regard to what actually took place, other than the standard stock phrases such as, ‘forcing the enemy to pull out,’ or ‘driven out with the bayonet.’ What really happened will never be fully known, but there are some tantalizing remarks concerning what took place inside a residence that was being defended against attack in Emile Zola’s masterpiece La Débâcle (part of the Les Rougon-Macquart novels, 1871-1893.) Here we get a good impression of what it was like to be embroiled in house to house fighting, and although only a work of fiction, Zola still did a great deal of research, including interviewing participants who had taken part in the battles he describes, to give us a plausible account of what this type of combat was like.

“At this very second there was an appalling crash. A shell had demolished a chimney of Weiss’s house and fallen on the pavement, where it went off with such an explosion that all the windows nearby were broken. A thick dust and heavy smoke at first hid everything from sight. Then the front of the dyeworks could be seen gaping wide, and Françoise had been flung across the doorstep, dead, with her back broken, her head smashed in….”

And again,

“…So the lieutenant had moved out of the yard of the dyeworks, leaving a sentry there,realizing that the danger was now going to be on the street side. He quickly disposed his men along the pavement, with orders that in the event of the enemy’s capturing the square they should barricade themselves in the first floor of the building and resist there to the last bullet.”

Finally,

“…Another house opposite was on fire. The crackling of bullets and explosion of shells rent the air which was filled with dust and smoke. Soldiers fell at every street corner and the dead, isolated or in heaps, made dark, bloodstained patches. Over the village, swelling in an immense clamour, was the threat of thousands of men bearing down upon a few hundred brave men resolved to die.” [32]Zola Émile. La Débâcle.

While basic tactics could be modified to suit a situation on the open battlefield, linear and column formations were of little use in house to house combat. In such situations the non-commissioned officers and even a well respected colleague, could do more than a colonel or major in instilling fighting spirit. Small numbers of troops without guidance fought more out of a sense of self preservation than anything else. Thus, if a house looked as if it was about to be either surrounded or obliterated troops would abandon it or surrender. Very few sensible soldiers held out until death.

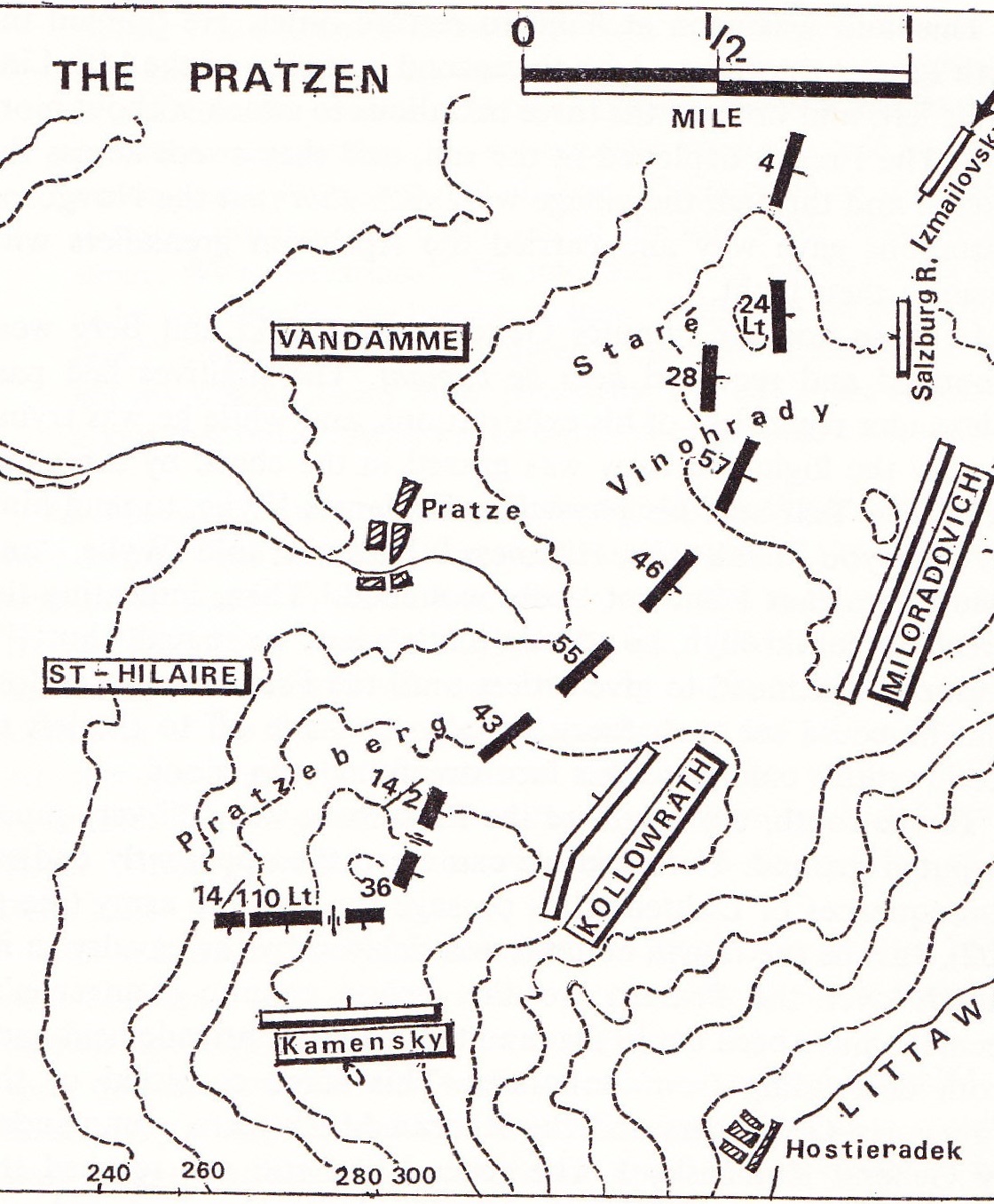

The Pratzen Heights.

Kamensky was late in bringing up his brigade owing to the confusion that had taken place during darkness when Liechtenstein, seeking to get to his designated position, pushed the 5th Column, consisting of 4,650 cavalry, through the marching infantry, causing confusion and delay. This, together with the fact that Kutuzov, despite this mix-up between foot and horse, still gave no instructions to the 4th Column to advance once their front had been cleared caused consternation on the part of the Russian monarch. Now occurred the famous exchange between Alexander and his chief with the Tsar saying curtly to Kutuzov: ‘Mikhail Larionovich! Why have you not begun your advance?’ to which Kutuzov replied, ‘ I am waiting for all the columns of the army to get into position sire.’ Alexander shot back, ‘But we are not on the Empress’s Meadow, where we do not begin a parade until all the regiments are formed up!’ ‘Your Highness,’ replied the old boy, ‘If I have not begun, it is because we are not on parade, and not on the Empress’s Meadow. However, if such be Your Highness’s orders.’ And at just around 8:45 am, the whole left wing moved forward. [33]Duffy, page 103.

The delays and confusion on the Allied side did have a knock-on effect when Soult’s IV Corps attacked the Pratzen. Thinking that the plateau would be clear of enemy units by 8:00 am, Napoleon had asked Soult how long it would take him to place his troops on the heights, to which the Marshal had replied that he could be there in twenty minutes. The Emperor then told Soult to wait another fifteen minutes to take advantage of the fog. Thereafter, at just about the same time that Kutuzov gave the order for the 4th Column to advance, Soult’s corps moved forward, fortified with a triple issue of army brandy. General Saint-Hilaire’s division moved to take the high ground on the right of Pratz village and General Vandamme’s division the vine planted slopes of the Staré Vinohrady, a mile to the left of Pratz. Behind Soult’s corps Napoleon had amassed most of his army. Marshal Lannes two divisions of the V Corps were posted across the Brünn-Olmutz road to the north, with Murat’s cavalry in close support. Marshal Bernadotte’s I Corps were closing up towards Girzikowitz with the Guard infantry and cavalry together with Marshal Oudinot’s combined grenadier division forming a general reserve close around the Zuran Hill, Napoleons HQ.

The Allied troops still on the Pratzen heights, besides Kamensky’s brigade, consisted of Miloradovich and Kollowrath’s 4th Column, of some 12,000 Austrian and Russian infantry with over 70 cannon. Also nearby was Grand Duke Constantine with the Russian Imperial Guard, 10,000 men and 40 guns posted on the high ground east of Blasowitz. Miloradovic’s not inconsiderable force was moving forward without any knowledge of the storm that was to break over them. Indeed, Major Karl Toll, who was riding ahead of the 4th Column with a solitary Cossack aide, was the first to catch a glimpse of indistinct masses of infantry appearing out of the mist. Thinking it was part of the 3rd Allied Column that had taken the wrong direction, Toll was soon made fully aware of the fact that they were French when a musket shot rang out causing him to study the now fast approaching troops again. The shock of encountering enemy units in such close proximity sent Toll racing back up the hillside. The first troops he encountered was Lieutenant-Colonel Monakhtin’s advance guard of Miloradovic’s 4th Column who immediately deployed the two battalions of the Novgorod Infantry Regiment to meet the French advance; one on the high ground to the south of Pratz, the other through the village itself, stationing them on a high point facing south that was concealed from the view of the French. One battalion of the Apsheron Infantry Regiment, together with two squadrons of the Austrian Erzherzog Johann Dragoon Regiment stood in and to the rear of Pratz in reserve [34]Castle, page 163..

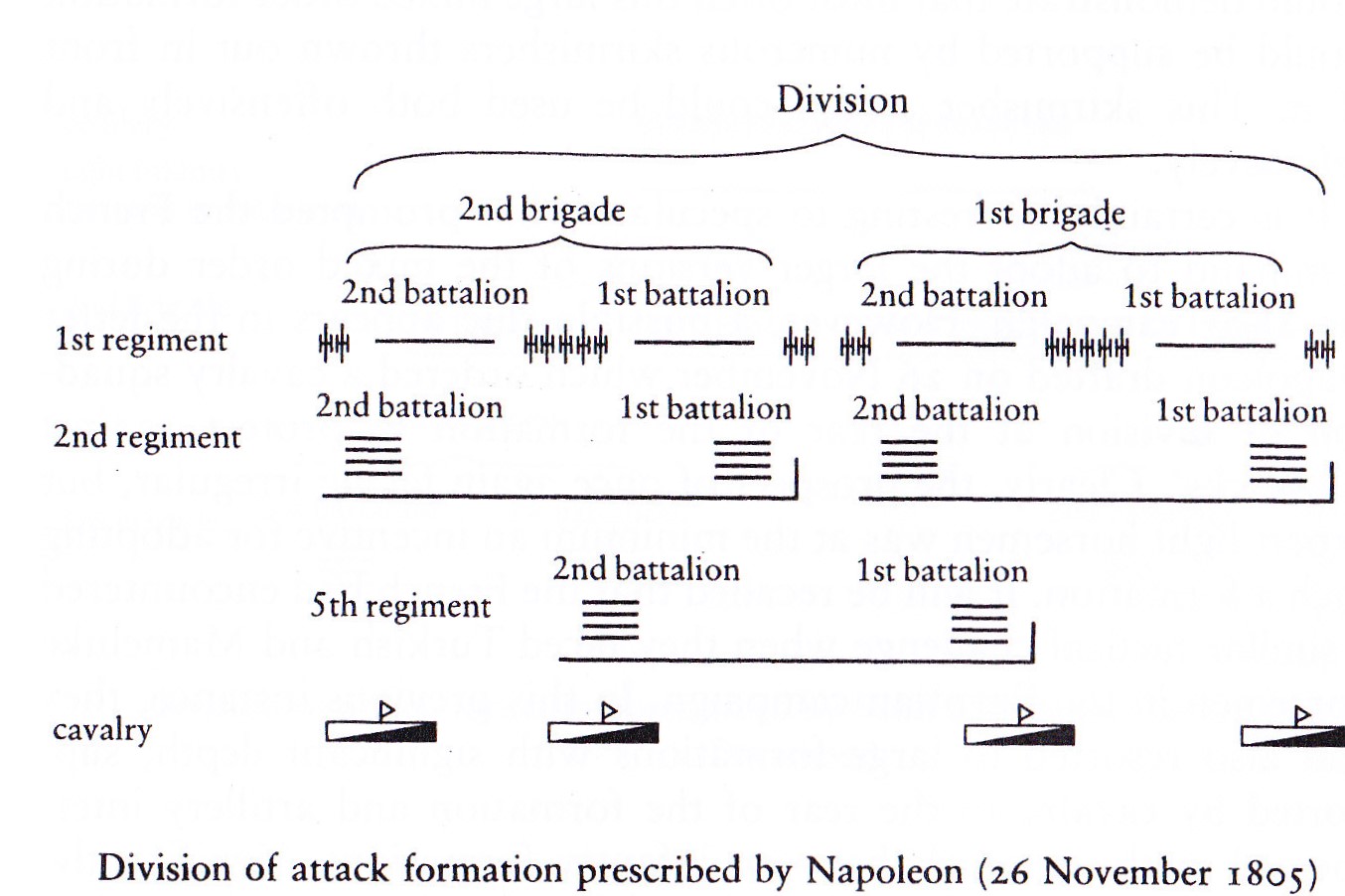

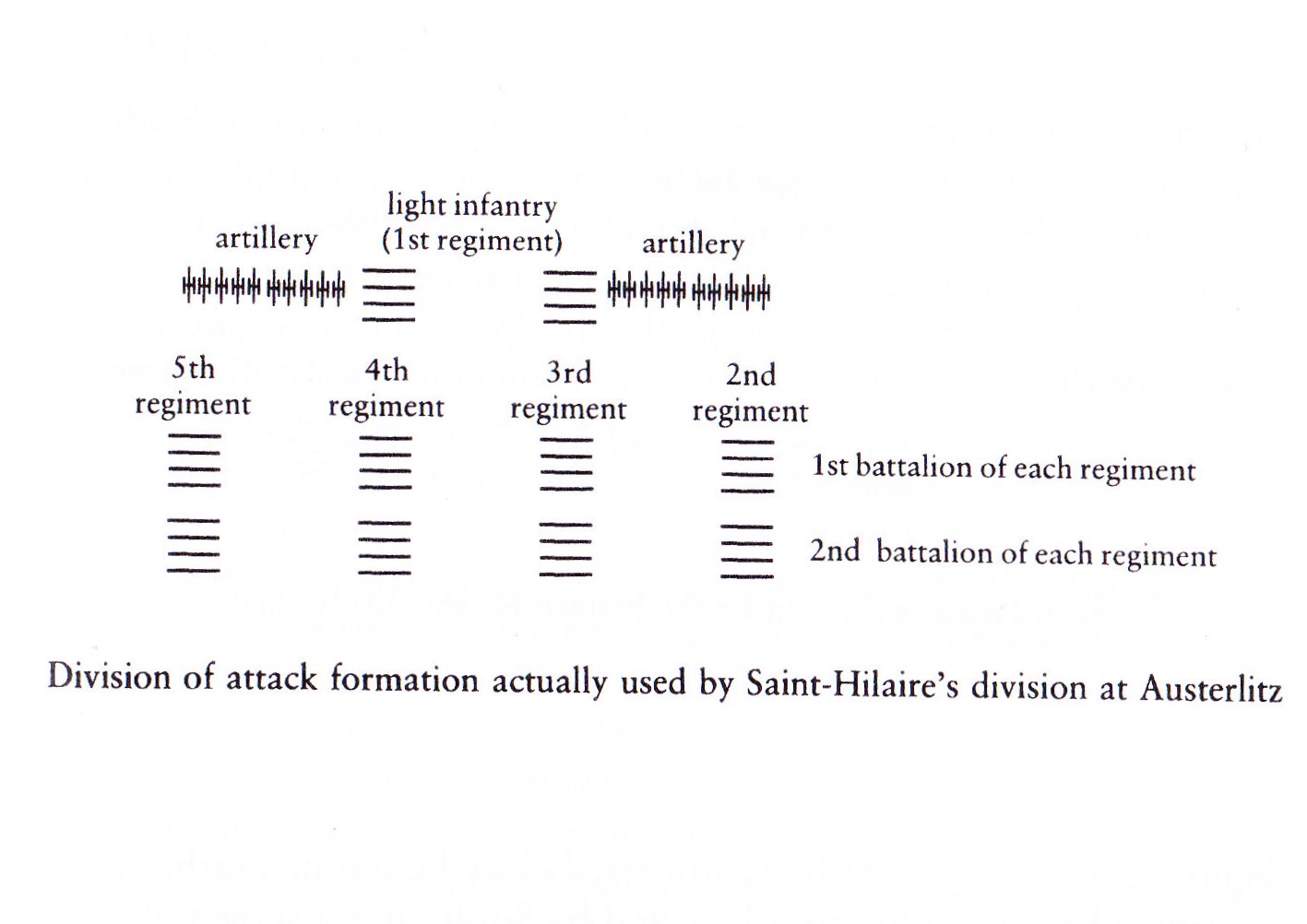

The actual attack formation of Soult’s IV Corps is questionable. Napoleon himself had prescribed how each division should be organized in a letter drafted on the 26th November, which included having cavalry accompanying them in the event of being attacked by Cossacks. Since this was the first time he had faced the Russians, he obviously expected these light cavalry to present the same problem that he had encountered in Egypt when he had come up against the Mameluke’s [35]Nosworthy. Brent, Battle Tactics of Napoleon and his Enemies, page 134..

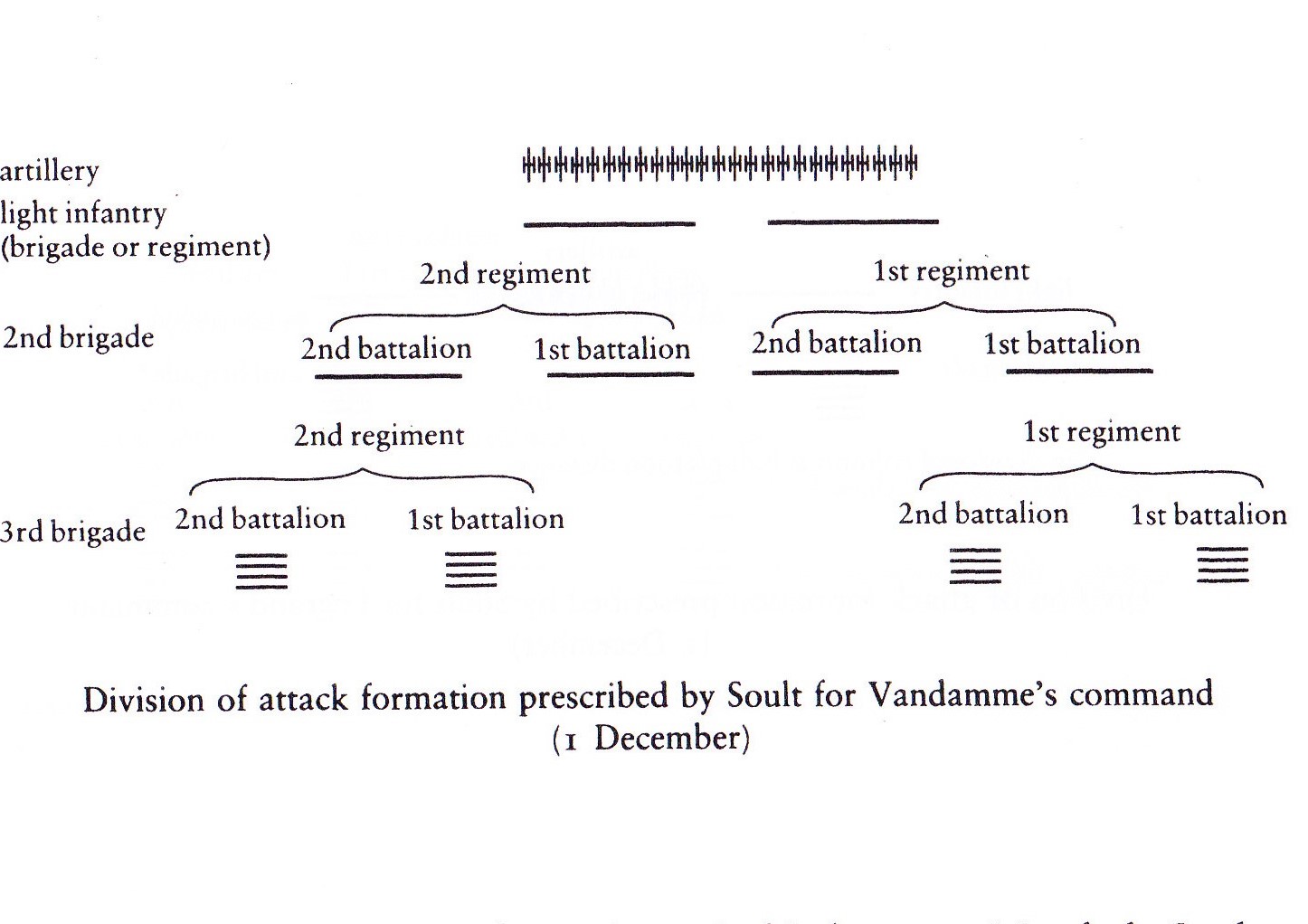

It is worth quoting Nosworthy at some length here in order to obtain a better example of how versatile French commanders and their formations had become at this time:

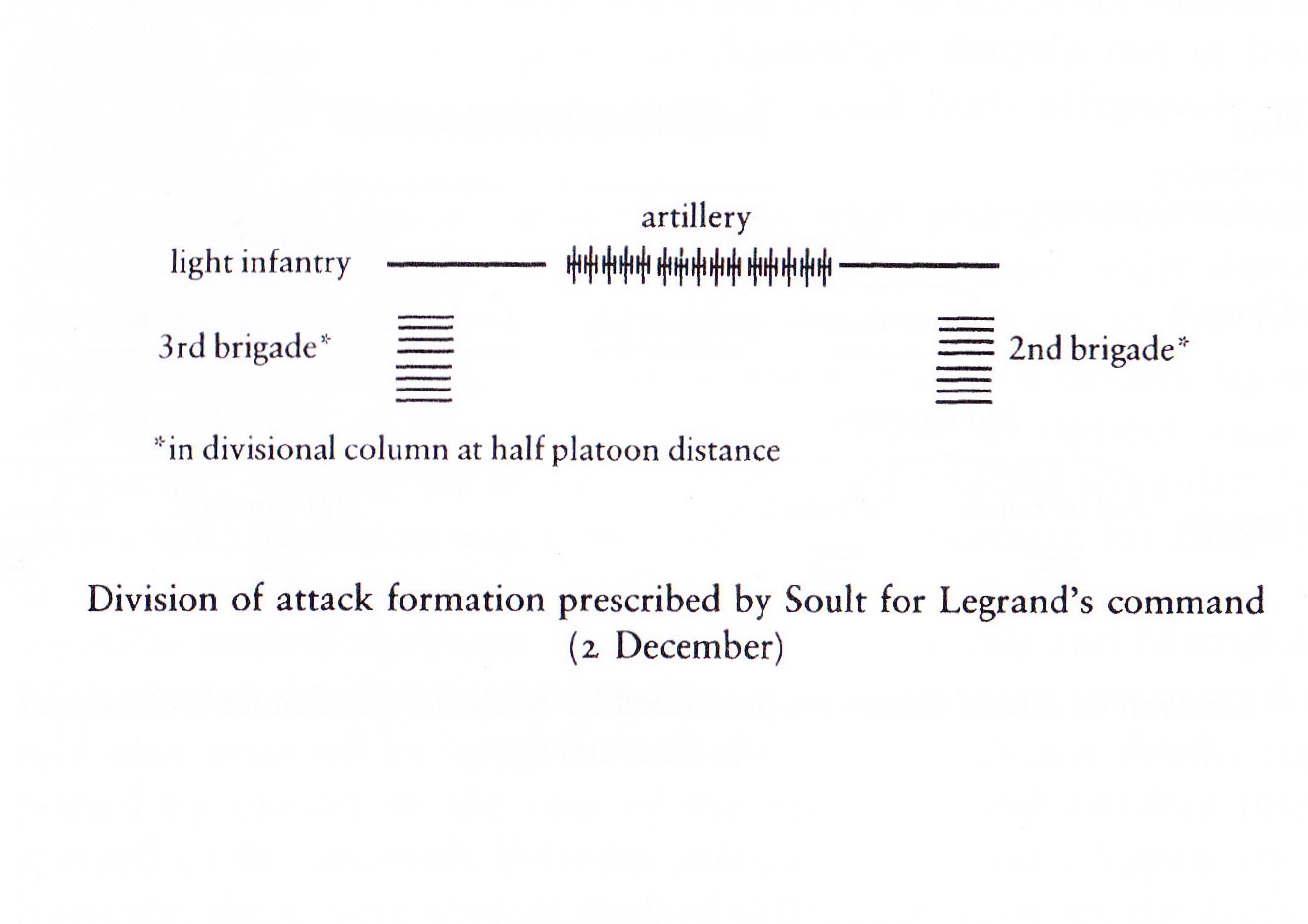

‘Interestingly enough, as events turned out, despite Napoleon’s efforts to dictate the exact position of each of the elements making up a division, it did not prove to be entirely successful. Though the divisional mixed order formation was indeed used on the battlefield, it always in some unique form differed slightly from the model proposed by Napoleon. Marshal Soult, for example, did not hesitate to alter quickly the official model, and several days later on 1 December issued his own set of instructions for Vandamme’s division. The infantry formations were to be protected by artillery and light infantry positioned to its front. The divisional artillery was positioned as the lead element, while the light infantry, a regiment or even a brigade in strength, stood 100 paces in front of the two brigades of regular infantry behind it. In this proposal, the first brigade of regular infantry was deployed in line while the four battalions of the second brigade remained in column behind the flanks of the battalion in line’.

‘For his other division, commanded by General Legrand, on 2 December Soult devised yet another version of divisional level mixed order. This time, the artillery was guarded with light infantry on either flank rather than slightly to the rear. The infantry of the two brigades or regular infantry remained in a divisional column at half intervals, i.e. the column was a division of a battalion wide with space between each tier in the column equalling the frontage of a platoon. Neither of these plans was actually employed during the battle of Austerlitz. Michiels in his work, Au soleil d’Austerlitz, distilled Marshal Soult’s after-battle report and compared it with Colonel Poitevin’s journal and a ledger drawn up for the 4th de ligne and the 24th légére. He concluded that the artillery and light infantry regiment were in column of division stationed along the division’s front. Each battalion within the two line regiments was formed in column by divisions seperated at platoon distance. This yielded four columns in two tiers.’

‘It is on these three lines of columns that Saint-Hilaire’s division, in front of Puntowitz, and Vandamme in front of Girzikowitz, were formed.’

Formation diagram taken from Nosworthy.

‘It is interesting to look at the initial deployment of French forces at the beginning of Austerlitz. In the area between Girzikowitz and Stanton almost all of Caffarelli and Suchet’s divisions were in columns of attack. Caffarelli’s ten battalions were deployed in three waves of columns, each separated from its neighbour by an ‘entire distance’, that is, the space needed to deploy that battalion into line. The exception was the 17th légére which was positioned on the Stanton. Suchet’s division, on the other hand, was in two waves of columns of attack. The units in Bernadotte’s corps were similarly configured. Both Drouet and Rivaud’s divisions were placed in three waves of attack, all at ‘entire distance’. The guard was similary deployed in close columns at full distance between battalions in the same wave, and the cavalry of the guard were in regimental closed columns by squadrons. The artillery in each of these divisions was placed in the intervals between the battalions, as instructed by Napoleon’s letter of the 26th November.

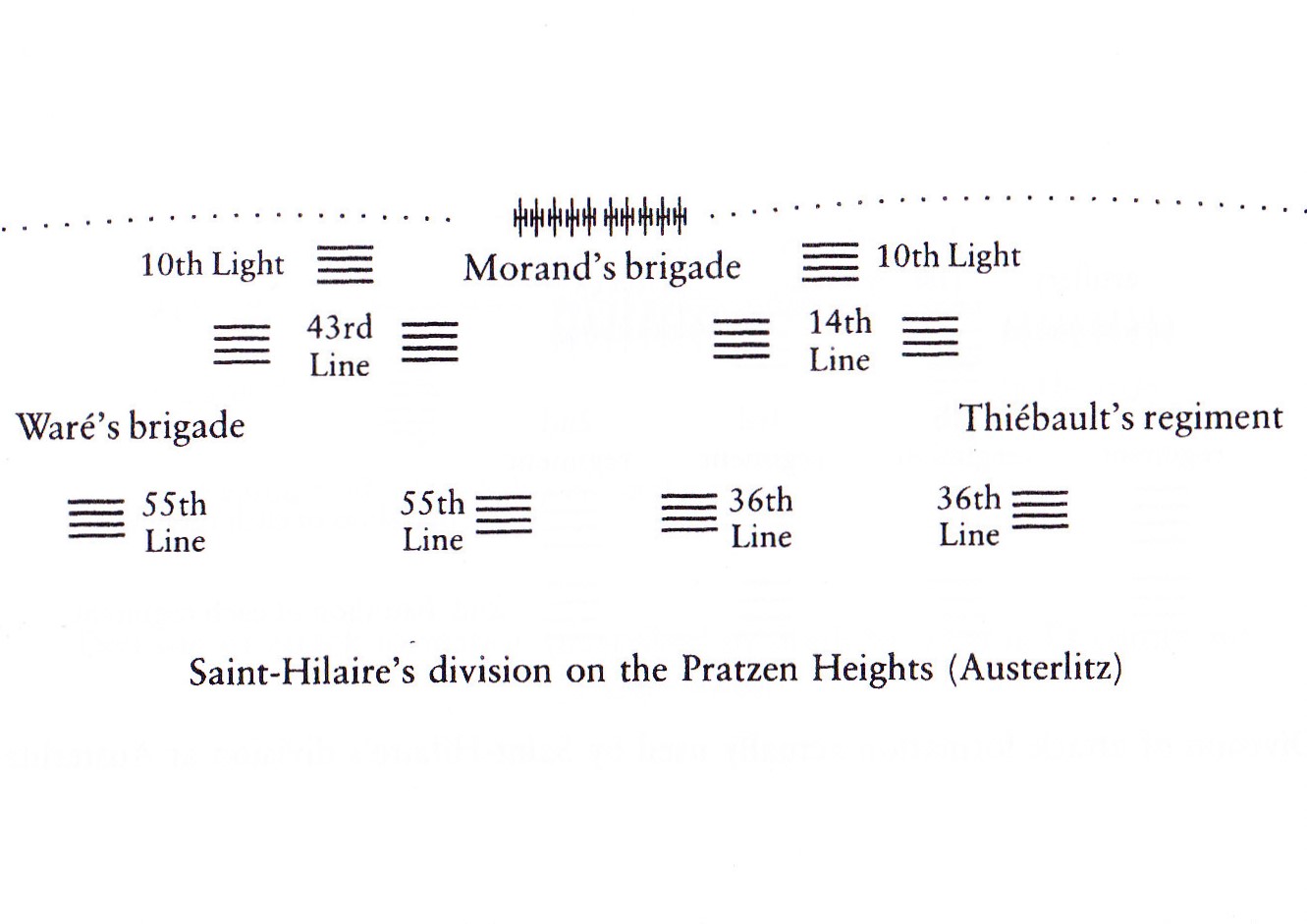

Just prior to the French assault on the Pratzen Heights the French infantry in this area were ordered to deploy from the ordinary closed columns into ‘attack columns on the centre’. Saint-Hilaire’s division, though not strictly in mixed order, adopted a division formation loosely similar to that given to Soult’s corps on 2 December. The difference was in Saint-Hilaire’s version the brigades in the rear were deployed in a number of battalion-sized close columns, rather than the single brigade columns advocated by Soult, and a screen of skirmishers was thrown out in front with the divisional artillery at their centre [36]Nosworthy, page 132-138..

Just prior to the French assault on the Pratzen Heights the French infantry in this area were ordered to deploy from the ordinary closed columns into ‘attack columns on the centre’. Saint-Hilaire’s division, though not strictly in mixed order, adopted a division formation loosely similar to that given to Soult’s corps on 2 December. The difference was in Saint-Hilaire’s version the brigades in the rear were deployed in a number of battalion-sized close columns, rather than the single brigade columns advocated by Soult, and a screen of skirmishers was thrown out in front with the divisional artillery at their centre [36]Nosworthy, page 132-138.. Once again one should not take for granted any prescribed formations “after contact with the enemy has occurred”. The French articulation of formations was equally adapted by commanders at all levels, and it was not unusual for a personal aide of a general to take control of a battalion or regiment as circumstances dictated in order to carry out a specific operation.

Once again one should not take for granted any prescribed formations “after contact with the enemy has occurred”. The French articulation of formations was equally adapted by commanders at all levels, and it was not unusual for a personal aide of a general to take control of a battalion or regiment as circumstances dictated in order to carry out a specific operation.

If finding the French climbing the Pratzen had come as a shock to Toll, the French themselves were equally surprised to find Allied troops still on the hillside. After receiving a warm reception from Monakhtin’s rapidly deployed battalions the French skirmish line fell back as Kollowrath also came up directly in the path Saint-Hilaire’s advancing division, while the remaining troops of Miloradovich deployed against Vandamme.

Soult had instructed Saint-Hilaire to go around Praze village so that no time would be lost in fighting for its possession, however it appears that Soult was informed that the village was only lightly garrisoned by the Allies and taking this dubious information seriously he had then ordered Saint-Hilaire to clear the village as he advanced; this task being allotted to the 1st Battalion of the 14th Line Infantry Regiment under Colonel Mazas. Because not much opposition was expected, the battalion had no skirmishes thrown out in front, consequently, when it was suddenly fired upon by the Novgorod battalion stationed in the village, the shock, coupled with a withering volley of musketry, caused the French to fall back in disorder [37]Castle, page 163..

The main body of Saint-Hilaire’s division was pressing on up the slope, the 10th Light Infantry Regiment leading (see diagram) under General Morand, with General Thiébault following with his brigade. Seeing the disorder caused as the battalion of the 14th Line were falling back, Thiébault steadied the shaken troops and managed to restore order. Thereafter he ordered the 14th Line and the 36th Line to attack Praze, which was carried out with such speed and elan, that the Novgorod and Apsheron defenders were put to flight [38]Duffy, page 116..

As Duffy states:

In these horrible minutes Generals Repninski and Berg were wounded and rendered ‘hors de combat’. The fugitives fled past Alexander regardless of his exhortations, and while he was trying to stay the flight Kutusov was grazed in the cheek by a musket shot….Then indicating the French breakthrough, he added, ‘that’s where we’re really hurt! [39]Ibid, page 116.

Having consolidated his brigade, Thiébault suddenly noticed large regimental formations approaching from the east. Unable to identify if these troops were friend or foe Thiébault arranged his three battalions in a single line with its right bent back at right angles facing Kamensky’s forces and the left facing the approaching unidentified masses. Here, once again, we see the adaptability of the French army. Their ability to articulate from column into line and back without loosing cohesion had reached its peak in 1805-1806. Austerliz and Jena/Auerstädt are the best examples of the French infantry using lines and mixed order groupings, and not, as happened in later years, the massed column. Even the astute and adaptable Marshal de Saxe had to resort to the head-on massed attacks at times, stating that if there was no utility to manoeuvring on the battlefield, after the initial deployment of troops (in linear formation), there is little to do but simply advance straight forward to resolve the issue. The French certainly, at this time, had the most adaptable professional army in Europe.

Thiébault was not convinced that the approaching regiments were friendly and together with General Morand, dismounted and crept forward to get a better view. It did not take long for them to discover that they were hostile when an officer from Kamensky’s command galloped across to confer with them. With confirmation that they were about to be attacked from two directions, Thiébault and Morand dashed back to their respective commands to prepare to receive them [40]Duffy, page 117..

In fact the approaching formations were Austrian, and it is quite possible, allowing for the cold weather and murky conditions, that the reason for them being difficult to identify in the first place was because they were probably wearing their great coats. Indeed, since these items were similar in both the French and Austrian armies, and were of a grey colouring, the confusion is understandable. But now that their identity was known the French unmasked a battery of nine cannon, the fire from these coupled with a massed musket volley caused the enemy regiments to stagger and fall back, but only briefly, soon the Austrians linked up with Kamensky’s brigade and came on again on a wide front. Here General Jurczik was badly wounded, and General Weyrother himself was unhorsed and fell to the ground, brusied and shaken. Things became so serious that Saint-Hilaire even considered falling back to a less exposed position. He was however dissuaded of doing so by Colonel Pouset, commanding the 10th Light Infantry, who soon convinced him to drive on and clear everything in front of them, in this way the enemy would not have time to see how few their assailants really were [41]Ibid, page 119..

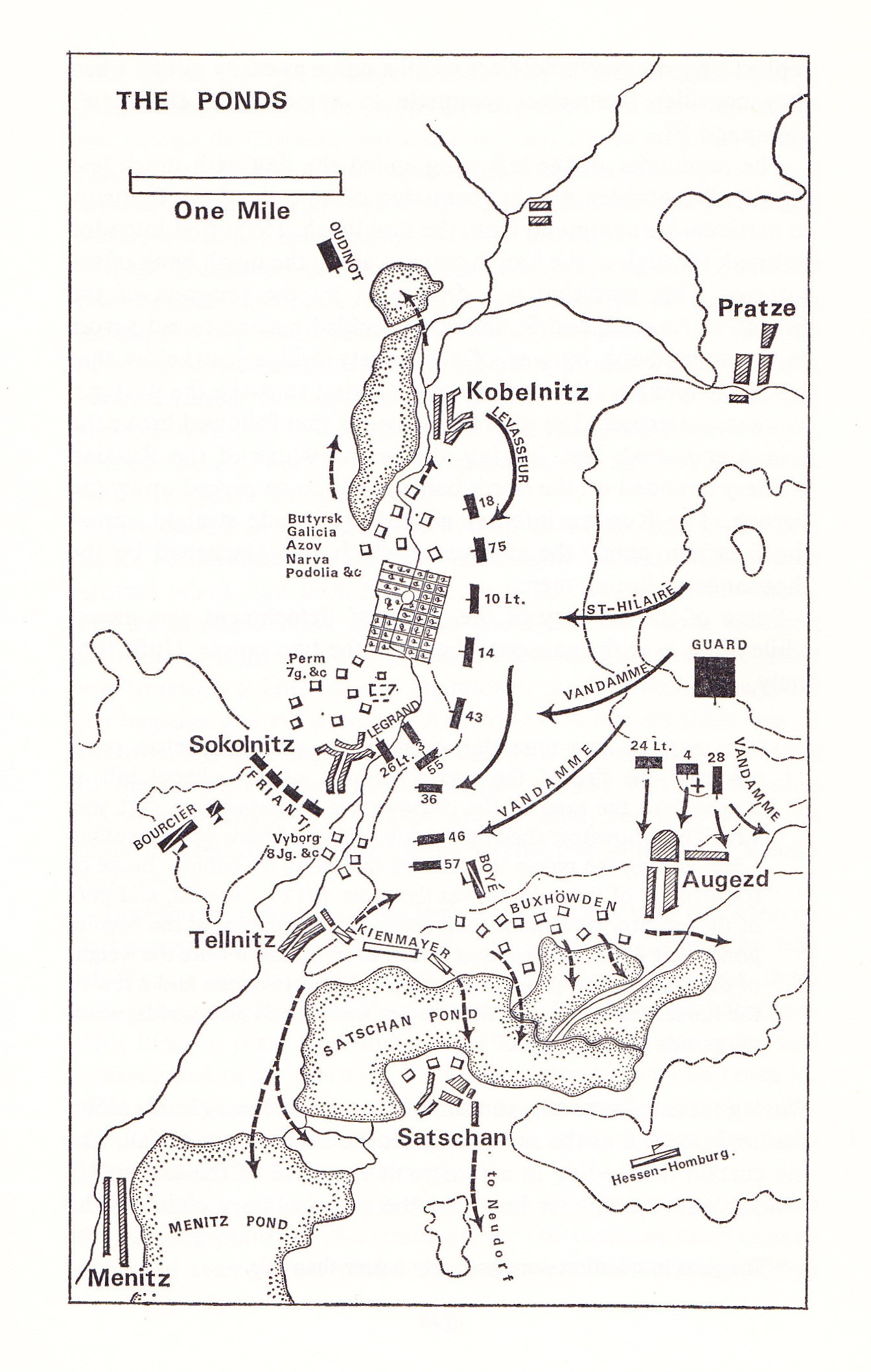

While the battle raged on the Pratzen hights, General Langeron, still not beliving that the French were actually on the hilltop, decided to check out the situation for himself and was soon made aware that the situation on the Pratzen was serious. Galloping back down to the plain he found the Kursk Infantry Regiment plodding back towards the summit, with the Podolia coming up some way behind (see map). Taking charge of the regiment Langeron headed back up the hillside, but upon arriving on the top discovered that Kamensky’s brigade had been broken and that he was now going to be assailed from two sides as General Levasseur’s brigade had arrived on the hilltop hitting him in the flank. After a brief attempt to deploy facing both threats, the Kursk regiment was almost completely destroyed, all its standards and cannon were taken together with suffering a staggering 1,600 men killed, wounded or captured out of a total strength of 2,000. The Podolia’s three weak battalions coming up behind were driven back into the pheasantry near Sokolnitz castle. By 11:00 am the French were definitely in control of the Pratzeberg [42]Duffy, page 120..

To the north General Vandamme’s division had been slowly advancing against Miloradovich’s 5,000 troops, all that he had to hand from the 4th Column. Here the French had a considerable advantage in numbers, since besides Vandamme’s three brigades numbering 7,600 men, Varé’s brigade of Saint-Hilaire’s division was also avalible adding a further 3,200 troops to his strength. The four Allied battalions under General Berg who had been advancing towards Pratze village gave ground slowly in the face of French pressure, but soon lost heart when Berg was wounded and fell back in some disorder. Miloradovich himself brought forward his remaining five battalions in an effort to stem the onrushing French. This second line of defence consisted of General Rottermund’s Austrian brigade comprising of 3,000 men of the Salzburg Infantry Regiment and one battalion each of the Kaunitz and Auersperg Infantry Regiments, 1,500 men. Behind these Miloradovich rallied his retrating Russians, forming them on a battalion of the Izmailovsy Lifeguard Regiment which had been sent in support by the Tsar. The Austrians put up such a stubbon resistance that Vandamme had to make a concerted attack using Férey’s brigade and the 55th Line Infantry Regiment on the right with Schinner’s brigade coming in on the left, this combined assult finally driving the remnants of Rottermund’s brigade from the Pratzburg. Miloradovich’s 4th Column had virtually ceased to exist. As that general himself stated, ‘up till then the troops had put up a stubbon fight. But now the cumulative effect of the catastrophic situation, their own exhaustion, the lack of cartridges, the disadvantageous lie of the land, and the enemy fire which came in from every side, all made them give way in disorder.’ [43]Ibid, page 121.

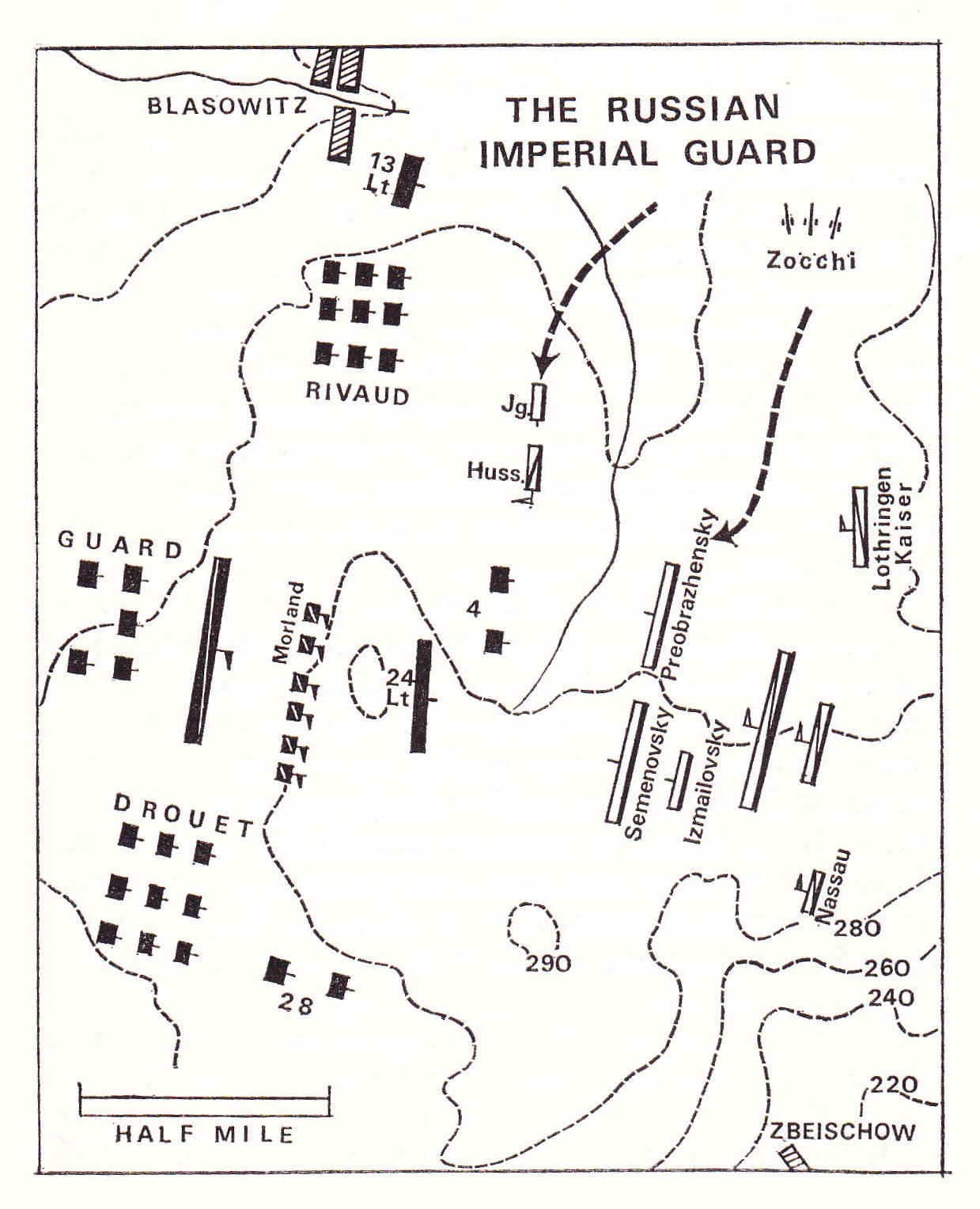

Vandamme had indeed cleared the Staré Vinohrady but was soon to have his success challenged by the formidable Russian Imperial Guard.

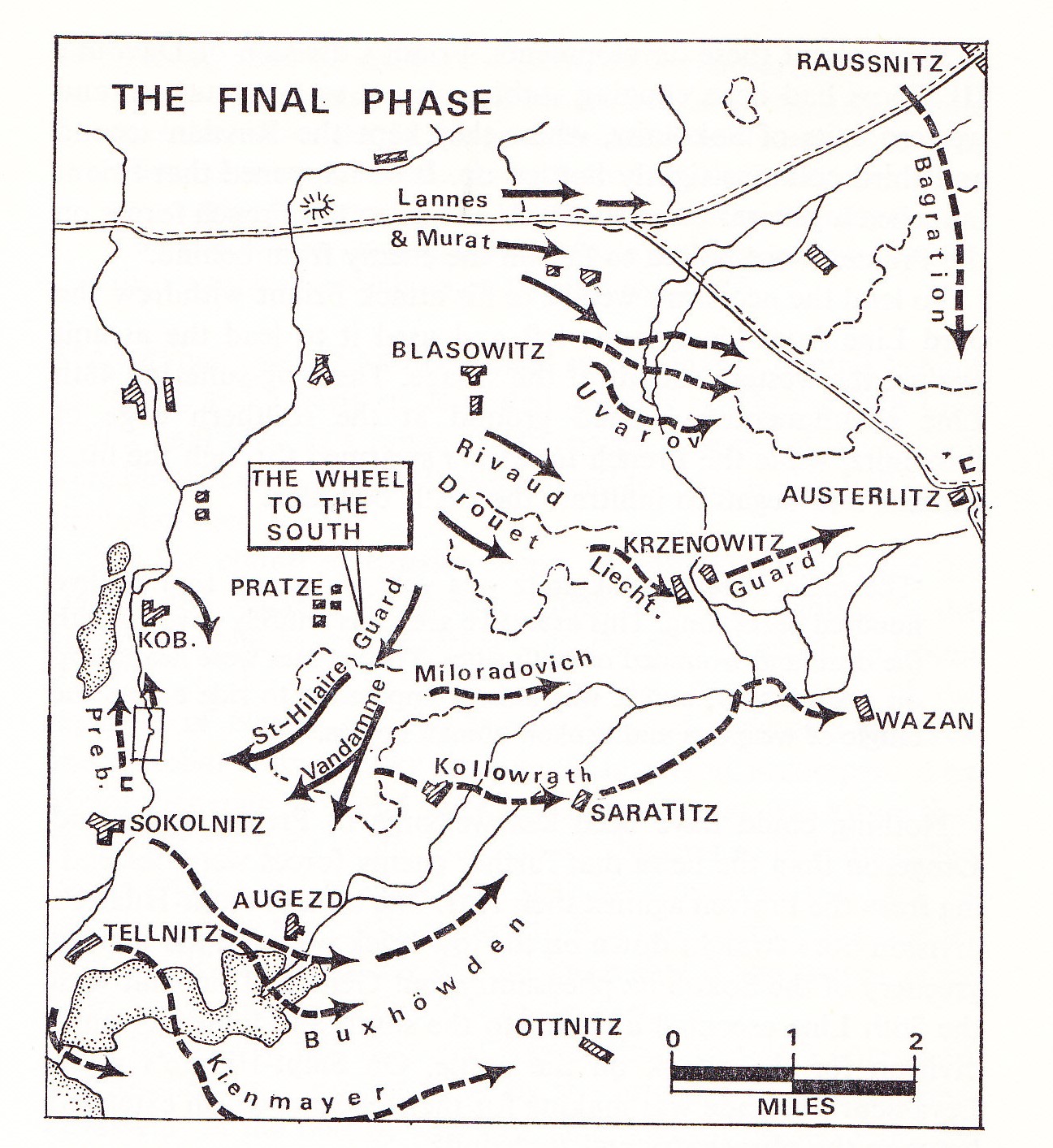

Away to the north the French V Corps under Marshal Lannes and the Russians under Prince Bagration were about to engage in their own private battle, mainly due to the fact that Napoleon had not expected Lannes, together with Murat cavalry, to have met with much resistance on this part of the field, thinking that the majority of the Allied forces were now committed to the southern sector. He had therefore instructed Lannes and Murat to hold their position until Soult was firmly ensconced on the Pratzen plateau, after which they were to move forward cutting off the Allies line of retreat towards Olmütz. The bitter struggle that now ensued came as a surprise to the somewhat overconfident French Emperor.

Having caused delays and confusion during the early hours, Lichtenstein’s cavalry had arrived in the void that seperated Bagration’s command from the rest of the Allied army, around the area of Blasowitz, Krug and Holubitz. Here Lieutenant-General Hohenlohe detached the Austrian Lothringen Cuirassier Regiment towards the Staré Vinohrandy where signs of trouble seemed to be taking place, the rest of Lichtenstein’s cavalry then moved to fill the yawning gap in this part of the Allied line. As the various squadrons deployed, a battalion of the Russian Guard Jäger came up and occupied Blasowitz village. [44]Duffy, page 123.

At 10:00 a.m., Napoleon had received news that Soult had established a tentative grip on the Pratzen, thereafter he sent orders for Lannes and Murat to go forward, Kellerman’s light cavalry division pushed out in front. With the Russian Guard Jäger battalion in Blaswitz about to be overwhelmed, Lichtenstein quickly organised his cavalry for action. With the Lothringen cuirassiers and a battery of horse artillery protecting the left of the village, Lichtenstein now decided to attack Kellerman with Essen II’s four regiments of Russian cavalry, some 30 squadrons strong. This plan unfortunately came to nothing, as before the Russian brigades could complete their deployment, the 1,000 troopers of the Grand Duke Constantine Uhlans, rather than waiting for this to be completed, were ordered by Essen II to attack the enemy directly. With their artillery batteries unable to support this advance owing to their own cavalry being in the line of fire, the uhlans came on alone at full-tilt, with lance pennants flapping wildly in the breeze. Without awaiting the impact from this dashing horde of wide eyed green coated demons, Kellerman’s squadrons retired back through the gaps opened up by the French infantry who thereafter, with parade ground precision, closed ranks once their mounted colleagues had passed and delivered a crashing volley into the onrushing lancers. This, together with a crippling discharge of cannister from the French artillery, caused the uhlans to veer off to the right galloping along the front of Lannes two infantry divisions from which they received still more punishment, and finally fetching up well behind their own lines, having lost 400 killed and wounded, including Essen II himself who had accompanied the charge, being so seriously wounded that he would die later. [45]Castle, page 172-173. Duffy, page 124.

Once the threat from the maruding Russian uhlans had been dealt with the French infantry once more opened their ranks to allow Kellerman’s troopers to pass to the front. While this operation was in progress the three remaining Russian cavalry regiments, the Kharkov Dragoons, Chernigov Dragoons and the Elizabetgrad Hussars, who had not taken part in the unsuccessful charge made by their lancers now came forward, catching the French 4th Hussar Regiment before it had time to complete its deployment, hacking many of them down before the remaining regiments of Kellerman’s division came up, striking the Russians in front and flank. As the various French and Russian squadrons hacked and stabbed at each other in a swirl of kaleidoscopic colour, General Sébastiani bought up his brigade of dragoons from Walther’s division, driving into the crush causing the Russians to fall back in some disorder. [46]Castle, page 173.

With both the French and Russian cavalry reforming Bagration began to move forward from Posorsitz, to engage the left flank of Lannes corps, which was ancored on the village of Kovalowitz; Bagration had occupied Holubitz and Krug with the 6th Jäger Regiment, covered by a couple of Sotina’s of Cossacks with the Elisabetgrad Hussars covering their left. The 5th Jäger Regiment and the Mariupol Hussars were pushed out covering his right flank. Between these groupings Bagrations infantry advanced in two lines with the Tver Dragoon, Empress Cuirassier and the St Petersburg Dragoon Regiments following. The rapid advance of the 5th Jäger towards the village of Siwitz drove back the French outpost, but they soon came under fire from the battery (ironicly of captured Austrian cannon) on the Santon hill. Undetered the Jäger took Bosenitz and then pushed on until being stopped by the concentrated fire from a battalion of the 17th Light Infantry and the artillery on the Santon, causing them to fall back to Bosenitz. As they were reforming around the village the other battalion of the 17th Light descended from the Santon and came on against them driving them back, the Jägers only being saved by the Mariupol Hussars and Cossacks who attempted to cover their withdrawal. With the arrival of Milhaud’s and Treillard’s light cavalry the threat to the French left flank was removed. [47]Castle, page 174.

The French left may have now been secure but for the opposing cavalry the struggle raged on violently, with Kellerman’s light squadrons and Walther’s dragoons wheeling in and out of combat with their Russian counterparts whom General Ermolov, watching the cavalry combat, stated, ‘ In our cavalry, as in the rest of the army, the majority of actions were uncoordinated, without any consideration of mutual support. And thus from one wing to another our forces came into action by detachments, and one after the another they were put into disorder, overthrown and chased off the field [48]Quoted in Duffy, page 129.

The French, on the other hand, had far more command and control, with artillery, infantry and cavalry working as a unified whole and giving each other support. Murat, irritated by the Russian hit and run cavalry tactics, now decided to throw his “heavies” into the fray. These consisted of Nansouty’s and d’Haupoul’s curassier and carabiniers, some thirty squadrons strong. As these masses were moving forward, Murat, at the head of Walther and Kellerman’s divisions, hit the now weary Russian horsemen but still failed to put an end to the issue. Finally, the cuiassiers and carabiniers interveaned, driving the Russians back, but this once again was only briefly. As Nansouty regrouped behined the cover of Caffarelli’s infantry, a Russian Hussar regiment carried out a spoiling attack against the French 13th Light Infantry who were on the far right of the infantry line. These young troops proved their worth by opening a destructive musket fire at close range which emptied many saddles and drove the now suitably chastised hussars back in some disorder; Nansouty now once more moved forward, hitting the main Russian body of cavalry causing them to retire tattered and greatly weakened [49]Castle, page 174..

Now that the field was clear of the threat from the enemy cavalry, Lannes ordered Caffarelli to take Blasowitz from the Russian Guard Jäger. These well diciplined troops greeted the advancing French with a steady and accurate fire, making them falter and pull back. Another assault failed and only when a combined effort was made by both battalions of the 13th Light Infantry and the 51st Line Infantry, were the Jäger’s finally driven out. As they withdrew they fell back into the ranks of a battalion of the Semeyonovsk Guard Infantry Regiment that had been forming behined Blasowitz. Caffarelli’s men forcing them to retire in their turn [50]Castle, page 175..

Before noon Lannes and Bagration’s infantry, each some 5,000 strong, came into real contact, over a plain littered with dead and wounded Russian cavalry. The Russians were drawn up in compact masses receiving the French with a tremendous fire from infantry and artillery. As General Suchet stated:

‘Drawn up in lines, our infantry withstood the canister fire with total composure, filling up the files as soon as they had been struck down. The Emperor’s orders were carried out to the letter, and for perhaps the first time in this war, most of the wounded made their way to the dressing stations unaided [51]Duffy, page 129.

Not only were the Russian infantry hard pressed by the steady advance of the two French infantry divisions but, now being free from any major threat from Russian cavalry, d’Hautpoul’s cuirassiers came in threating their right flank. However, this was soon disposed of by a concentrated platoon fire which made the heavies retire leaving their infantry to once more continue advancing.

Falling back slowly Bagration set up a defensive position around Welleschowitz and was reinforced by the welcome arrival of an Austrian battery of twelve cannon under the command of Major Frierenberger which deployed on a rise of ground near the Posorsitz post house, firing with such accuracy that the French artillery, accompanying their infantry, had to pull back out of their range, this, in turn, causing a knock-on effect which stalled the advance of the infantry. The road to Hungary was now secure, and Bagration was able to join the main army [52]Duffy, page 131..

As Bagration moved his forces to block any attempt to cut off the army’s line of retreat, two regiments of Russian cavlary were still south of the highway. These troopers belonged to General Uvarov’s brigade, acompanied by a battery of horse artillery. Seeing Bagration withdrawing, Uvarov put in a spoiling attack against the French, then withdrew across the Raussritz stream, there joining up with the Chernigov Dragoon Regiment.

Liechtenstein’s cavalry had also been in action attempting to slow the advance of Rivauld’s division of Bernadotte’s I Corps, which was moving towards the village of Jirzikowitz. The Nassau Cuiassier Regiment and the Kaiser Cuirassier Regiment were bought foreword to support the Lothringen Curassier’s to the south-east of Blasowitz, the latter regiment then charging Rivauld’s advancing battalions, causing them to halt; like there Russian allies, the Austrian cuirassiers then continued to use hit and run tactics until they drew fire from Vandamme’s artillery on the Pratzen which caused them to retire out of range.

As already mentioned, at between 11:30 am and midday, the Russian Imperial Guard had been marching toward the rising ground south-east of Blasowitz, and had also started to receive the attention of French batteries. Their commader, Grand Duke Constantine had already detached a battalion of the Izmailovsky Guard Regiment to help on the Pratzen Heights, and these had become involved in the disaster that had befallen the Allied 4th Column. After this Constantine suddenly became aware that the Guard were now the only organized unit on this section of the battlefield capable of showing a bold front to the masses of French now moving onto the hilltop. Therefore, having received no futher orders on what was requied, Constantine thought it best to withdraw and join up with the remants of the 4th Column and attempt to form another defensive line, but soon ralised that he first had to try to stop or at least slow down the French advance, and now disposed his forces to meet their oncoming columns. This proved difficult owing to the fact that he was now threatened by Vandamme’s division coming over the Staré Vinohrandy and had to deploy the Semenovsky and the Preobrazhensky regiments together with the Guard Jäger to the eastern slopes of these vineyards in order to meet the threat, with the Guard cavalry covering the flanks. It was Constantine’s idea to contain the French advance as long as possible, then fall his troops back by sections through the village of Krzenowitz. Things developed rapidly, as both sides now engaged in a fierce musketry duel and the Russian Guard infanty then putting a bayonet attack. This charge caused the French to fall back, but their seconed line came on again in linear formation accompanied by massed battery fire from their supporting artillery. In an attempt to check this advance the Russian Guard cavalry now joined the fray [53]Stutterheim, page 110-112. Duffy, page 135. .

A Clash of Elites.

Vandamme, who had been slightly wounded and was in the process of having it dressed, noticed a large formation approaching and ordered Major Bigarré to take the 4th Line Infantry Regiment and check on its identity. When he arrived at the edge of the hilltop Bigarré became aware that the advancing formation was cavarly, coming on at a steady trot. Bringing up the first battalion of the 4th Line Bigarré ordered it to form square in preparation for a cavalry attack. However, once they had formed square, the Russian Guard cavalry peeled away right and left and revealing a six gun battery which raked them with canister fire. The 24th Light Infantry Regiment was sent to help their beleagured comrades in the 4th but before they came up Contantine had thrown his squadrons against the now weakened 4th. Managing to beat back the first charge from two Russian mounted regiments, the French infantry were in the process of reloading when a third regiment of horse rode into the square, sabering and stabbing over 200 men, and capturing the battalion eagle. Upon seeing the fate that had befallen the 4th, the 24th Light formed line in an attempt to bring their full firepower into play, but their linear formation now allowed the Russian troopers to ride straight over their extended ranks. [54]Duffy, page 136.

Napoleon had left his command post on the Zuran hill and had now arrived at the Staré Vinohrandy in time to see mass of infantry fleeing in panic in his direction and the fact that many of them kept looking back over their shoulders as they ran confirmed that they were French, and that they were being persued by cavalry. This episode was made somewhat amusing by the fact that although the French infantry were running away as they fled passed Napoleon they cried Vive l’Empereur, bringing a wry smile to the Emperor’s face [55]Duffy, page 136.. Nevertheless, something had to be done, and with Marshal Bessiéres just coming up with the French Imperial Guard cavalry these were now used to rectify the situation.

But at first it was a case of too little too late, as Napoleon ordered one of his aides, General Jean Rapp, to take only two squadrons of Guard chasseur-a-cheval, supported by a squadron of Guard mounted grenadiers and a half squadron of Mamelukes to deal with threat. At first Rapp made headway against the now mixed up Russian horse who, after a brief engagment with their opposite number, withdrew, allowing the Prebyshevsky and Semenovsky Guard Infantry regiments to receive them on the point of their bayonets, which now caused the French cavalry to become disordered in their turn. Seeing this Constantine now hit them with three fresh squadrons of the Chevalier Guard, causing Rapp to dissengage and fall back to reform. After a brief period each side came on again and now a general cavalry battle ensued pitting Horse Guards aginst Horse Guards; the Russians 1,800 strong, the French around 1,100. [56]Ibid, page 137; Castle, page 186-187. In this mass swirl of smoke and flying clods of earth the French came off best, being able to rally on their own infantry formations and then continue the contest, the Russians not having the benefit of this luxury owing to their own infantry being in the middle of the cavalry fray and therefore unable to fire for fear of hitting their own mounted comrades, consequently the Russian Guard cavalry sustained greater casualties. Finally, after suffering substaintial losses, they withdrew and fell back towards Krzanowitz, covered by their own retreating Guard infantry and Hohenlohe’s three strong Austrian cuirassier regiments, who seem to have been fully aware of the cavalry fight, but did not intervene. With the arrival of Bernadotte’s I Corps and the Guard the Pratzen Plateau was at last totally secure, Napoleon now turned his attention south. It was almost 2:30 pm.

Saint-Hilaire’s division and Férey’s brigade of Vandamme’s, turned to their right and began to desend the Pratzen heading towards Sokolnitz village. Vandamme’s other two brigades under Varé and Schinner struck out for the high ground overlooking Augezd village cutting off the escape exit of the Allies. The Imperial Guard followed on behind. Legrand’s division, pushing on from Kobelnitz, joined up with Saint-Hilaire’s right flank, while Boyé’s dragoons came up in rear of Vandamme, together with a brigade from Oudinot’s Combined Grenadier Division. As this was taking place, Friant’s battered and much reduced division of III Corps were still holding desperately to the fringe of Sokolnitz, bottling up the Russians from advancing north. By either luck or good judgement Friant chose this exact moment to put in a counter attack which just happened to coincide with the advance of the French from the plateau, thus striking the Russians in front and flank. The fighting became bitter with houses, barns and stables becoming miniature strongholds, the Russians defending themselves with the utmost gallantly. Unable to obtain any information regarding operations on other parts of the battlefield, and seeing that he could well now be cut off from escaping south, Prebyshevsky now decided to break through to the north. Unfortunately not only were elements of Friant’s command still stubbornly holding out around the exits from Sokolnitz, but Morand’s and Levasseur’s brigades, together with Oudinot’s grenadier brigade, now put in a combined attack in the gathering dusk which resulted in the capture of over 4,000 men, together with Prebyshevsky himself. What remained of Langaron’s 2nd Column and Dokhturov’s 1st Column with Keinmayer’s advance guard were forced back but their escape route was now being threatened by the advance of Vandamme’s and Boyé’s dragoons.

At just before 4:30 pm Napoleon had reached the small chapel of St Anthony on the south-eastern edge of the Pratzen Plateau. The hillside here is very steep and broken up by a terrace that overlooks the village of Augezd. Napoleon sat his horse here and studied the situation through his telescope. He could see that maybe 10,000 or 12,000 of Buxhöwden’s Russians were still putting up a bold resistance and attempting to escape, therefore, in order to make his victory more resounding, he was impatient to get troops east of Augezd and cut the road to Hostieradek. Soon however Vandalism’s troops arrived and the situation then changed drastically. Pushing on from Augezd the French forced the Russians back towards the Satchen pond where they were pounded by artillery and musket fire, compelling them to surrender.