6th September 1813.

‘I have known a few men who were always aching for a fight when there was no enemy near, who always were as good as their word when the battle did come. But the number of such men is small.’ Ulysses Simpson Grant.

One among such small numbers who were always aching for a fight and were as good as their word when battle was joined was Michel Ney, Duke of Elchingen, Prince of Moskowa and Marshal of France, known by the sobriquet, The Bravest of the Brave.

*oil on canvas, *65 x 55 cm, *1812

Born at Saarlouis on 10th January 1769, the second son of a barrel – cooper, Ney first worked as a mine overseer, quitting that job in 1787 and enlisting as a hussar in the French army of the Old Regime, rising slowly to the rank of sergeant major during the upheavals of the French Revolution and becoming lieutenant and aide – de – camp to General Lamarche in 1792- 93. Thereafter Ney commanded 500 cavalry under General Kléber in the Army of the Sambre and Meuse.

Wounded at the Seige of Mainz in 1794, he was promoted to the rank of General of Brigade in August 1796. He led a cavalry charge at the battle of Neuwied in 1797 where he was captured and later exchanged. Promoted to General of Division in 1797 he commanded cavalry units in the armies of Switzerland and the Danube. He fought at Winterthur, where he was wounded, and at Hohenlinden in December 1800, under General Moreau.

Soon coming to the attention of Napoleon Bonaparte, not least by a dynastic marriage to a young protégée of the future Empress Josephine, Angaée Louise Auguiée, Ney was named Marshal of the Empire on 19th May 1804.

Despite his successes in the campaign of 1805, Ney began to show signs of headstrong and over – zealous behaviour during the following year at the battle of Jena, where he attacked prematurely, causing Napoleon much displeasure. Likewise during the 1807 campaign in Poland, Ney, although no doubt with good intentions, moved his corps out of winter quarters without informing the Emperor, in an endeavour to find a better foraging area some 60 miles into East Prussia. He was attacked and forced to retire, bringing about a resumption of hostilities which brought on the bloody but indecisive battle of Eylau (February 7th – 8th 1807) and finally culminated with Napoleon’s resounding victory at Friedland (June 14th 1807)

His conduct and insubordination to Marshal’s Massena and Soult in Spain in 1808 caused the former to finally dismiss him from the army in 1811. Napoleon, however chose to overlook Ney’s behaviour and gave him command of the camp at Boulogne. [1]Napoleon’s Marshals. Edited by David Chandler.

The disastrous Russian campaign of 1812 was to show Ney at his best. His handling of the rear- guard during the retreat from Moscow is one of the great epic tales of military history. Unfortunately 1813 was to prove how unfit Ney was for independent command and how limited his powers of tactical ability when confronted with the pressures and control demanded in overseeing large formations on a battlefield. At the battle of Lutzen (2nd May 1813), Ney dispersed his five divisions without adequate reconnaissance and failed to detect his enemies approach. At Bautzen (20th – 21st May 1813), given command of a four corps army, he failed to follow Napoleon’s instructions and halted, then took it upon himself to attack the enemy rather than cutting off their retreat as the Emperor had intended. These faults seem to have had little effect on Napoleon, who, doubtless knowing Ney’s limitations still continued to place much trust in his ability as an independent army commander.

The German campaign of 1813 was, for Napoleon, one of Pyrrhic victories and lost opportunities. Because of the vastness of the area of operations he was at times forced to divide his forces into separate armies, not always led by competent leaders and each force certainly nothing like the composition of Napoleon’s Grande Armée of former years in regard to the quality and reliability of their officers and men. Even so, considering the hardships and gruelling conflicts that took place during the campaign, the young recruits, French, German, Italian and Polish that fought to save a tottering throne, were to show great courage and endurance which, given better leadership, could indeed have at times made a difference to the outcome of events in 1813, if not perhaps to the eventual overthrow of Napoleon. Thus, while Napoleon achieved a great victory over the allied Army of Bohemia at Dresden (26th – 27th August), his detached forces under Marshal’s Macdonald and Oudinot had suffered defeats at The Katzbach (26th August) and Grossbereen (27th August) respectively, with General of Division Vandamme’s detached I Corps being almost totally destroyed at Kulm (29th – 30th August).

The Army of Berlin.

Oudinot, now out of Napoleon’s favour due to his mishandling of his forces at Grossbeeren, was reduced to commanding his original XII Corps, but still part of the Army of Berlin. His demoted circumstance did not sit well with the disgruntled marshal, and consequentially was to have a profound effect on how thing would eventually turn out.

There are two letters from Napoleon’s chief of staff, Marshal Alexander Berthier, to Ney dated 2nd September explaining the Emperor’s intentions for the army. The first letter informs Ney that he is now commander and that, in Napoleon’s opinion, it is situated around Jüterbog, forty – five miles south of Berlin. It goes on to say that Ney should have the army advancing on Berlin by the 4th September and that, “ His Majesty will be on the right bank of the Elbe and take an intermediate position between Berlin and Görlitz, not too far from Dresden.” From this it would appear that Napoleon himself intended to march on the Prussian capital in support of Ney’s movements [2]Leggiere. Michael V, Napoleon and the Struggle for Germany, page 356 -357.

The second letter from Berthier expands Napoleon’s plans, taking into account that he was now aware that in fact Oudinot had pulled back his troops to Wittenberg. He informs Ney that he has now selected Luckau as the “intermediate position between Berlin and Görlitz,” and Berthier states that, “The emperor instructed me to inform you that everything here is preparing to move to Hoyerswerda where His Majesty will have his headquarters on the 4th. Thus, it is necessary for you to start your march on the 4th so that you are at Baruth on the 6th.” How much contempt Napoleon had for the allied Army of the North is shown in his reference to it as being “all this cloud of Cossacks and pack of bad Landwehr,” predicting that if Ney proceeded with determination it would retire in panic [3]Ibid, page 357. Like a chess master who underestimates a lower grade opponent because he thinks himself superior, Napoleon was in for a nasty surprise.

Events were soon to overtake Napoleon’s plans as Blücher continued to harass Macdonald’s shaken and demoralised Army of the Bober after its defeat on the Katzbach. Unaware of the actual state of Macdonald’s army, which had been reduced to 20,000 effectives and had fallen back on Bautzen, it soon became apparent to Napoleon that his presence was needed to check Blücher and restore the morale and rebuild Macdonald’s depleted forces. On 3rd September he departed Dresden for Bautzen, already having issued orders for the Imperial Guard and Marshal Marmont’s VI Corps together with the cavalry corps of Latour – Maubourg to march in that direction. After realising that he had Napoleon on his front, Blücher in accordance with the Trachenberg – Reichenbach plan not to give battle when the French Emperor himself was on the field, duly fell back to Görlitz. Napoleon followed him but avoided the temptation to be lured away from Dresden and retired back to Bautzen from where, on the 6th September, he once more decided to proceed north to support Ney’s move on Berlin. It was too late.

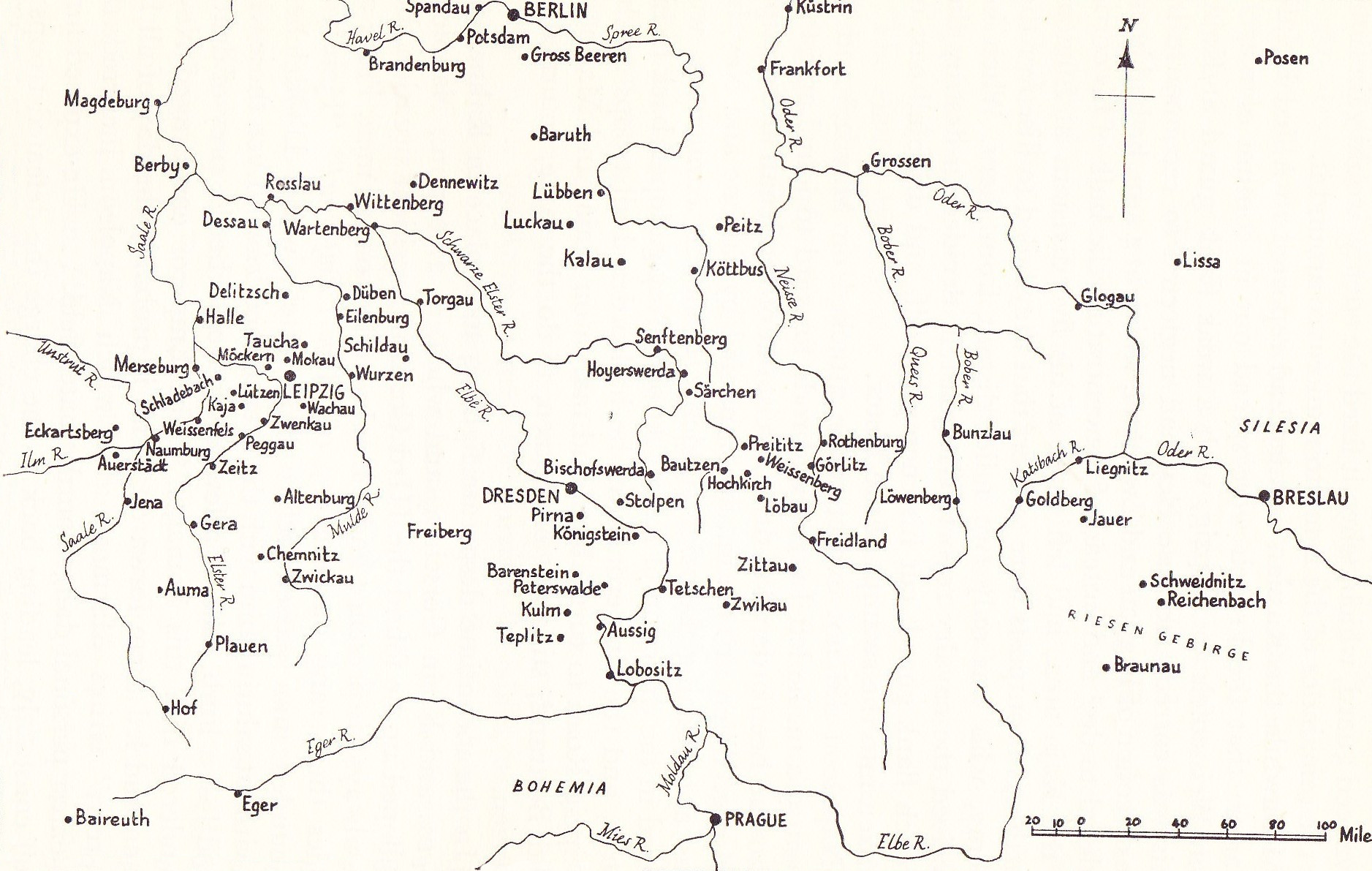

Upon Ney’s arrival to take command of the demoralised Army of Berlin on the 3rd September its corps were spread out in an arc north of Wittenberg. Oudinot’s XII Corps was holding the centre with Arrihgi’s III Cavalry Corps, with Bertrand’s IV Corps on the right and Reynier’s VII Corps on the left (see map).

Some accounts state that Ney wasted precious time reviewing his troops upon his arrival but it would seem that much of his time was taken up with consolidating his forces and attempting to form a suitable staff. His lack of aides and other administrative office’s had been compounded by Oudinot’s reassignment as corps commander and taking his whole staff with him, leaving Ney with only a handful of competent men capable of taking on army responsibilities. [4]Keefe. Major John M, Failure in Independent Tactical Command: Napoleon’s Marshals in 1813, page 33, Monograph published by the United States Army Command and Staff Collage. It is interesting that a … Continue reading

After receiving additional reinforcements which brought his strength up to around 60,000 men, Ney set his army in motion on the 5th September. Because of Oudinot’s original advance on Berlin having been made with his corps too dispersed, Ney choose to keep his forces on one road, advancing towards Zahna with IV Corps leading, followed by VII Corps then XII Corps. Arrighi’s III Cavalry Corps seems to have been doled out protecting the flanks of the advancing columns. The reason why Ney decided to place all his forces on one road can be attributed to his following Napoleon’s advice too closely. The Emperor had stated that he thought Oudinot should have kept his army closer together, therefore Ney, not wishing to meet the same fate and his master’s displeasure, advanced in such a way that his corps and divisions were piled up one behind the other in a long column that stretched back for miles. There are arguments both for and against Ney’s choice of advance, but a close look at the terrain in the area during this period shows poor lateral road connections with dense wooded areas covering a great deal of the landscape, making communication difficult. Ney did order VII Corps eventually to take the road to Baruth, becoming a flank guard for the remainder of the army and also threatening the right of any enemy forces that were found at Zahna. However, he failed to push forward an advance guard and never used his cavalry to determine the whereabouts of his foe. [5]The American military historian, Theodore A. Dodge, considers Ney at fault for following Napoleon’s instructions to the letter. See, Keefe. Major John M, Failure in Independent Tactical Command: … Continue reading

The composition of the Army of Berlin is a good example of how much Napoleon depended on his allies to bulk out his forces. Bertrand’s IV Corps contained German, Polish and Italian units; Reynier’s VII Corps was made up mostly of Saxon and French regiments, with a Wurzburg regiment and Saxon and French artillery; Oudinot’s XII Corps had two French divisions and one division of Bavarians, while Arrighi’s III Cavalry Corps was made up entirely of French regiments and French horse artillery batteries. [6]See OOB below

The various divisions were led by competent generals, and the lower ranking officers and NCO’s proved themselves capable, if not particularly enthusiastic. Equipment and mounts were good and the morale of the army was lifted upon Ney taking over command. What was desperately needed was a victory that would restore the soldiers confidence in Napoleon, a confidence that had been eroded by a string of defeats which, in turn, led to the feeling that the master had lost his touch.

The Army of the North.

The allied Army of the North was tasked with guarding Berlin, the capitol of Prussia. Its commander, the Crown Prince of Sweden and former marshal of France, Bernadotte, was one of the most enigmatic figures of the Napoleonic Wars. More interested in self advancement than in military matters he seldom missed a chance to further his own aims and, after accepting the Swedish crown, making sure that he took care preserving the Swedish units under his command and thus his own reputation in the eyes of his adopted country. The real driving force behind the Army of the North was General Friedrich Wilhelm Freiherr (Baron) von Bülow, the 68 year old commander of the III Corps. This corps, with the exception of its 5th Brigade under general Borstell which contained Swedish artillery and Russian light infantry and hussars, was otherwise made up entirely of Prussian units as was the IV Corps under General Bogislav Friedrich Emanuel Graf (Count) von Tauentzien. This corps had one Cossack regiment, the rest of its units being Landwehr, a combination that had caused Napoleon’s caustic comments.

It was Bülow’s and Tauentzien’s corps that had stopped Oudinot’s first advance on Berlin on the 23rd August at Grossbeeren and now, on the 5th September, Ney’s forward elements clashed with Tauentzien’s Landwehr who were blocking their advance at Zahna. Bülow, some distance further to the west, was soon marching to his assistance but thus far without the knowledge of the French. Also the lacklustre Bernadotte began to draw his scattered formations closer together in preparation for an engagement. After a brief but bloody struggle Tauentzien pulled back his troops to the sandy plain around the village of Dennewitz. On the evening of the 5th Ney’s forces were as follows [7]Petre. F Loraine, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page 272. :

- XII Corps – Pacthod’s and Guillemont’s divisions around Saydra; Fournier’s cavalry division and the Bavarians under General Raglowitch bivouacked at Gadegast.

- VII Corps, in and around Zahna.

- IV Corps together with Lorge’s cavalry division around Seehausen and Naundorf.

6th September 1813: Ney gets carried away.

The ground over which the battle was to be fought is much the same today as it was in 1813, the railway line, wide roads and modern buildings being the only drastic changes to the landscape. The soil is typical of Brandenburg, sandy and prone to dust storms in dry and windy weather. Here and there woods, coppices and low knolls are dotted across an almost flat plain which is crossed by the Agerbach (Nuthe) stream as it runs in a deep but narrow course from Nieder Görsdorf through Dennewitz and then on to Rohrbeck. The whole countryside with the exception of the marshy areas along both the banks of the stream was accessible to all arms.

Although Ney has been criticised for not using his cavalry correctly in controlling his advance with an adequate screen, it must also be remembered that, given the experience of his corps commanders, they too also failed to use their own initiative by not pushing out their own patrols, each corps having its own attached cavalry units; Bertrand had almost 1,000 horsemen and Reynier and Oudinot over 1,000 each. Petre states that a strong north-west wind raised clouds of dust which obscured the view[8]Petre. F Lorraine, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page 272. , but this was only because the cavalry was helping to churn up the sandy soil already swirling in the wind by the tramp of thousands of feet together with artillery limbers and wagons. If mounted units had been out in front then a far clearer view of the landscape would have been available. The sand also caused problems during the battle, many units not being able to identify friend from foe owing to uniforms and horses being covered in a fine layer of dust.

Early on the morning of 6th September Ney issued orders to his corps commanders regarding their movements and destinations. Reynier’s VII Corps was to advance towards Rohrbeck, directing his march via Gadegast and Oehna. Oudinot’s XII Corps would wait at Sayda until VII Corps had cleared Oehna, then move on Dahme and Luckau where it would meet up with the forces under Napoleon which, as we now know, never materialised owing to Blücher’s aggressive actions and Macdonald’s failure to reorganise his shattered army. Bertrand’s IV Corps, setting out at around 8:00 a.m., marched on Jüterbog, covering the movement on Dahme.

Some confusion occurred when Reynier altered his line of march without informing either Ney or Oudinot, bypassing Gadegast and thus leaving Oudinot’s troops marking time at Sayda until well after 1:00 p.m. in the afternoon. [9]Petre. F. Lorraine, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page 272. Once again we have yet another example of experienced commanders seemingly either choosing to take matters into their own hands and redirecting troops from their original destinations or simply, like Oudinot, just sitting tight and not bothering to use his own initiative by getting his corps on the road. Of course there is the element of “sour grapes” to consider here regarding the latter; the marshal was, as we know, sulking after his censure from the Emperor and begrudged Ney’s appointment over him.

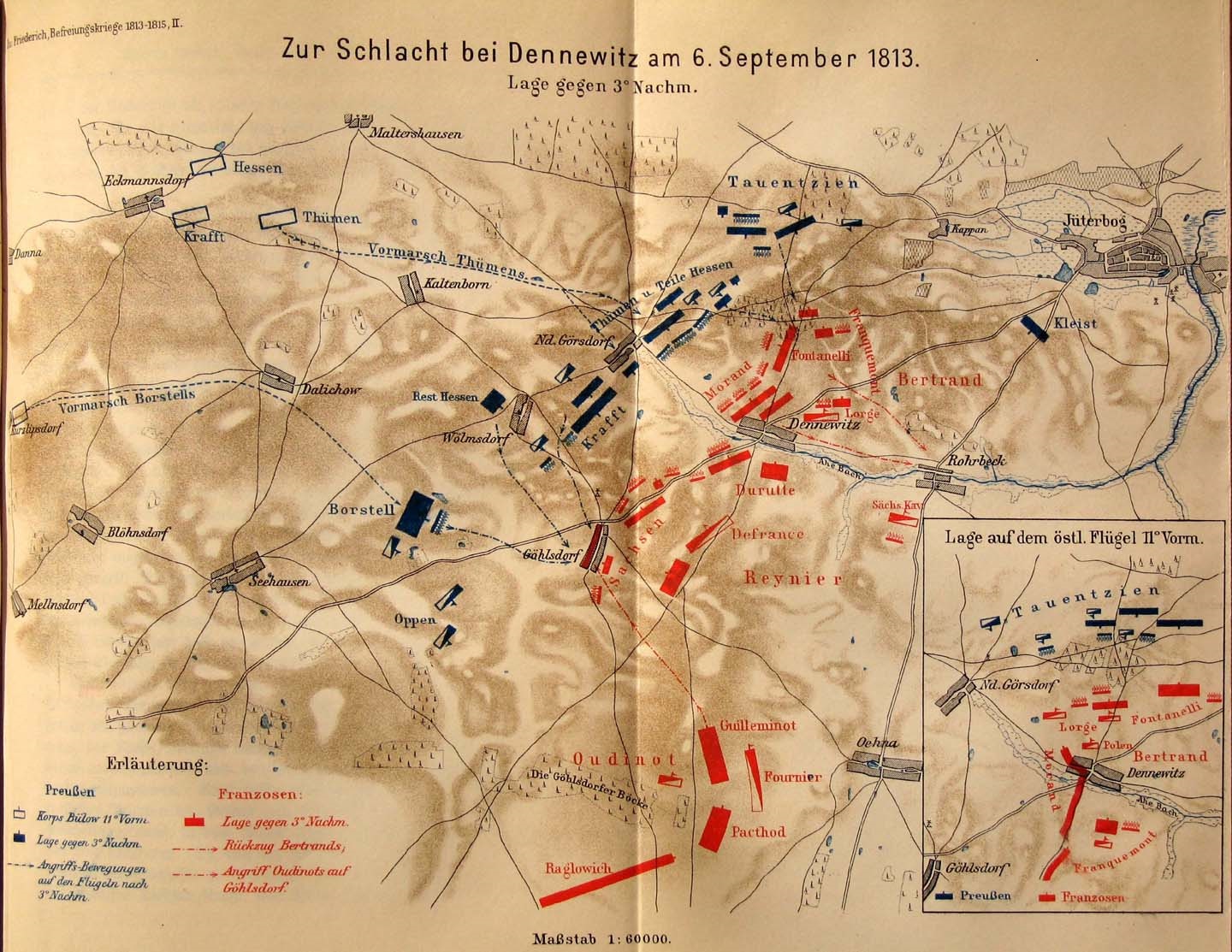

Bertrand’s IV Corps was covering the left flank of the Army of Berlin’s advance when, at around 11:00 a.m., it came under fire from the forward elements of Tauentzien’s Prussian IV Corps holding the high ground to the north of the village of Dennewitz. Tauentzien’s 10,000 men and nineteen cannon put up a solid resistance, but soon numbers began to tell as Bertrand brought his full force of 22,000 troops and sixty four guns into action, Fontanelli’s division pushing both wings of Tauentzin’s battle line back, while Morand’s division with Lorge’s cavalry took up a position in and around Dennewitz, on Fontanelli’s left. Franquemont’s division stood in reserve. However, Bertrand was forced to consolidate his position rather than push on and crush Tauentzine as large dust clouds to the west announced the arrival of Bülow’s III Prussian Corps on the field and as yet Reynier and Oudinot’s corps had not come up.

By 2:00 p.m.Morand had advanced his division as far as the rising ground around the village of Nieder Görsdorf but was forced to retire when Hessen – Homburg’s division put in a spirited attack. Pulling back and reforming his troops, Morand took up a new position running from the windmill at Dennewitz on the left, through that village itself, with his right flank resting on the wood just north – west of Nieder Görsdorf where it joined the left of the Franquemont’s Würtemberg division. The latter were now subjected to a fierce assault by the combined forces under Thümen and Tauentzine, and were driven back, forming a new line running from the right of Morand to the village of Rohrbeck. Seeking to stabilise and strengthen his position Bertrand now bought up Fontanelli’s Italian division between Morand’s right and Franquemont’s shaken Würtembergers. As they were forming they came under a concentrated fire from Landwehr units holding the wood -north west of Dennewitz and a brisk fire fight ensued which ended when Würtemberg and Italian units combined in attacking the wood in strength, driving the Prussians out.

While this was taking place Ney arrived on the field with the leading elements (Durutte’s division) of Reynier’s VII Corps. He immediately ordered Durutte to send a brigade to retake the windmill heights east of Dennewitz which had been taken by the Prussians, meanwhile Reynier moved his two Saxon divisions under Generals Lecoq and von Sahr into position covering Bertrand’s left flank. Durutte’s attack was driven back with heavy casualties and by 3:00 p.m. Thümen had cleared Dennewitz and was preparing to press his attack together with Krafft’s 6th Prussian Brigade now on the field. However, it began to look as if Ney’s order of march had proved to be correct as now, as each element of his army arrived, it extended the French position to the left and also brought in reinforcements at just the right moment and place blunting every Prussian attack. [10]Keefe. Major John M, Failure in Independent Tactical Command: Napoleon’s Marshal’s in 1813, page 36.

At just after 3:00 p.m. Oudinot’s XII Corps began arriving on the field and Bülow, now aware that he could be overwhelmed, ordered Borstell’s 5th Brigade forward to try and break Reynier’s hold on Gölsdorf; these troops were Bülow’s last infantry reserve. Driving the Saxons from the village the Prussians were forced back in their turn as Guilleminot’s and Pachtod’s divisions came up in support of Reynier’s hard pressed line. Having arrived at the right place at the right time, at 4:00 p.m., with his troops poised to aid Reynier in overwhelming Bülow’s right wing before Bernadotte could reach the field, Oudinot received orders from Ney to continue his march and join Bertrand in smashing through the Prussian left. This decision by the army commander, together with Oudinot’s supposed stubborn acceptance in conforming to his orders, has been seen as the cause of the French defeat. However, there is another possible explanation as to why Ney was so fixated in attacking the Prussian left wing to the detriment of all else.

Regardless of wind and dust obscuring Ney’s vision of the battlefield put forward in some accounts, and which therefore we may say would also be the same for the commanders on both sides, the real reason why he chose to concentrate his attacks in that particular region could well be his initial instructions from Napoleon – to march to Baruth and be there on the 6th. It will be remembered that he had been told that the Emperor himself together with at least one corps would be at Luckau to support him on that date and thereafter join him in the march on Berlin. None of the sources mention Ney having received any dispatches or messages stating that Napoleon had altered his plans and, consequently, in my humble opinion, the marshal was attempting to clear the way for a junction with, as we now know, the none existent forces promised by Napoleon.

This supposition can be backed up to some extent by what occurred during the Waterloo campaign of 1815 when Ney, given command of almost half of the French army, was suddenly deprived, without warning, of a whole corps on the 16th June when facing Wellington at Quatre Bras. The famous pencilled note which supposedly was sent to inform him of the situation has never been forthcoming, likewise then at Dennewitz, Ney was carrying out his orders as he saw them without any knowledge of his masters altered situation.

Whatever the cause, Ney’s decision proved to be his undoing. By 5:00 p.m. Oudinot, despite one of his regimental commanders halting and attempting to be of some assistance to the now hard pressed Reynier and his dwindling Saxon divisions, pushed on in compliance with orders at just the moment when Bernadotte was arriving on the field with his Swedes and Russians, as well as much needed artillery. With the arrival of these fresh troops Bülow’s battered but proud units came on again breaking Reynier’s formations and sending them retreating in confused groups eastwards. All was now confusion and despite Ney and Reynier’s gallant efforts to stem the rout by 6:00 p.m. the whole Army of Berlin was quitting the field in panic stricken rout, ‘…Reynier and Oudinot made direct for Torgau; Ney, with Bertrand, went towards Dahme, where they were joined by Raglowich’s Bavarians, who had scarcely been engaged…’[11]Petre. F. Loraine, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page 275. Casualties on the French side amounted to 22,000 of which some 13,000 were taken prisoner. They also lost over fifty cannon, … Continue reading: General of Division Durutte

- 35th Light Infantry Regiment……………..2 Battalions

- 132nd Line Infantry Regiment……………3 Battalions

- 36th Light Infantry Regiment……………..3 Battalions

- 131st Line Infantry Regiment…………….3 Battalions

- 133rd Line Infantry Regiment…………….2 Battalions

- Wurzburg Line Infantry…………………….2 Battalions

French XII/1st Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns:

French VIII/4th Horse Artillery Battery…6 gun:

French XXIV/2nd Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns:

French XXVI/2nd Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns:

French XXV/Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns:

French XIII/8th Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns:

Reserve Batteries:

- Saxon 1st Horse Artillery Battery…6 guns:

- Saxon 2nd Horse Artillery Battery…6 guns:

- Saxon 1st Foot Artillery Battery (12 pounder cannon)…6 guns

VII Corps Cavalry Brigade: General of Brigade Lindenau

Saxon Hussar Regiment

Saxon Prince Clemens Uhlan Regiment

XII Corps: Marshal of the Empire Oudinot

14,941 Infantry: 1,165 Cavalry: 66 guns

13th Infantry Division (French): General of Division Pacthod

- 1st Light Infantry Regiment……………..1 Battalion

- 7th Line Infantry Regiment………………2 Battalions

- 42nd Line Infantry Regiment…………..1 Battalion

- 67th Line Infantry Regiment……………2 Battalions

- 101st Line Infantry Regiment…………..2 Battalions

- French VI/4th Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns:

- French XX/4th Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns

14th Infantry Division (French): General of Division Guilleminot

- 18th Light Infantry Regiment…………..1Battalion

- 156th Line Infantry Regiment………….3 Battalions

- 52nd Line Infantry Regiment…………..2 Battalions

- 137th Line Infantry Regiment…………3 Battalions

- Illirian Infantry Battalion………………1 Battalion

- French II/4th Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns: French I/8th Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns

29th Infantry Division (Bavarian): General of Division Raglovich

- 1st Bavarian Jager……………………….1 Battailon

- 3rd Bavarian Infantry…………………..1 Battalion

- 4th Bavarian Infantry…………………..1 Battalion

- 8th Bavarian Infantry……………… 1 Battalion

- 13th Bavarian Infantry……………..1 Battalion

- 2nd Bavarian Jager…………………..1 Battalion

- 5th Bavarian Infantry……………….1 Battalion

- 7th Bavarian Infantry……………….1 Battalion

- 9th Bavarian Infantry……………….1 Battalion

- 10th Bavarian Infantry……………..1 Battalion

- 1st Bavarian Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns:

- 2nd Bavarian Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns:

- Reserve Artillery (French) III/5th Horse Artillery Battery…6 guns

XII Corps Cavalry Brigade (German): General of Division Beaumont

- Westphalian Chevauléger Uhlan Regiment

- Bavarian Chevauléger Regiment

- Hessian Chevauléger Regiment

III Cavalry Corps: General of Division Arrighi

6,092 Light Cavalry: 1,571 Heavy Cavalry: 24 guns

5th Light Cavalry Division (French): General of Division Lorge

- 5th Chasseurs- a- Cheval…….. 2 Squadrons

- 10th Chasseurs- a-Cheval…….2 Squadrons

- 13th Chasseurs-a-Cheval…….2 Squadrons

- 22nd Chasseurs-a-Cheval…….2 Squadrons

- 15th Chasseurs-a-Cheval……..1 Squadron

- 21st Chasseurs-a-Cheval………1 Squadron

6th Light Cavalry Division (French): General of Division Fournier

- 29th Chasseurs-a-Cheval……..1 Squadron

- 31st Chasseurs-a-Cheval……..1 Squadron

- 2nd Hussar Regiment………….2 Squadrons

- 1st Hussar Regiment………….1 Squadron

- 4th Hussar Regiment…………1 Squadron

- 12th Hussar Regiment……….1 Squadron

4th Heavy Cavalry Division: General of Division Defrance

- 27th Dragoon Regiment…….2 Squadrons

- 4th Dragoon Regiment (called back from Spain)….1 Squadron

- 12th Dragoon Regiment……1 Squadron

- 14th Dragoon Regiment……1 Squadron

- 13th Cuirassier Regiment…..3 Squadrons

- 24th Dragoon Regiment…….1 Squadron

- I/5th French Horse Artillery Battery…6 guns: V/5th French Horse Artillery Battery…6 guns: II/1st French Horse Artillery Battery…6 guns

Order of Battle for the Army of the North

Commander-in-Chief: Crown Prince Bernadotte

154,060 infantry and cavalry: 387 guns, of whom some 80,000 men and 250 guns were engaged.

Officer commanding on the field: Lt General von Bülow

IV Army Corps: Lt General Tauentzien

- 1st Silesian Landwehr Infantry Regiment…..3 Battalions

- 1st Kurmark Landwehr Infantry Regiment….2 Battalions

- 2nd Kurmark Landwehr Infantry Regiment….3 Battalions

- 5th Kurmark Landwehr Infantry Regiment….3 Battalions

- 3rd Prussian Reserve Infantry Regiment……..3 Battalions

- 2nd Neumark Landwehr Cavalry Regiment….2 Squadrons

- 3rd East Prussian Landwehr Cavalry Regiment…4 Squadrons

- 3rd Pomeranian Landwehr Cavalry Regiment…..4 Squadrons

- Russian Illovaiski III Cossacks

- 6th Horse Artillery Battery…4 guns:

- 11th Horse Artillery Battery…4 guns:

- 30th Foot Artillery Battery…4 guns:

- 27th Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns:

- 17th Heavy 6 pounder Artillery Battery…8 guns

III Army Corps: Lt General von Bülow

3rd Brigade: Major General Hessen- Homberg

- II/East Prussian Grenadier Regiment………….1 Battalion

- 3rd East Prussian Infantry Regiment……………3 Battalions

- 4th Prussian Reserve Infantry Regiment……….3 Battalions

- 3rd East Prussian Landwehr Infantry Regiment…4 Battalions

- 1st Leib Hussar “Death’s Head” Cavalry Regiment…4 Squadrons

- 5th Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns

4th Brigade: Major General Thümen

- East Prussian Jager Regiment ……………….1/2 Battalion

- 4th East Prussian Infantry Regiment……………….4 Battalions

- Elbe Infantry Regiment…………………………………2 Battalions

- 5th Prussian Reserve Infantry Regiment…………..4 Battalions

- Brandenburg Dragoon Regiment…………………….4 Squadrons

- 6th Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns:

- 12th Foot Artillery Battery…8 [12 pounder cannon]:

- Russian 7th Foot Artillery Battery…12 guns [heavy cannon]

6th Brigade: Colonel von Krafft

- Colberg Infantry Regiment……………………………..3 Battalions

- 9th Prussian Reserve Infantry Regiment…………….3 Battalions

- 1st Neumark Landwehr Regiment……………………..3 Battalions

- West Pomeranian Dragoon Regiment………………..2 Squadrons

- 1st Pomeranian Landwehr Cavalry Regiment………4 Squadrons

- 16th Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns: Russian 21st Foot Artillery Battery…12 guns [heavy cannon]

Reserve Cavalry: Major General von Oppen

- Prussian Queen’s Dragoon Regiment………………….4 Squadrons

- 2nd West Prussian Dragoon Regiment………………….3 Squadrons

- 2nd Kurmark Landwehr Cavalry Regiment……………3 Squadrons

- 4th Kurmark Landwehr Cavalry Regiment…………….3 Squadrons

- Pomeranian Landwehr Cavalry Regiment………………3 Squadrons

- 5th Horse Artillery Battery…8 guns: 6th Horse Artillery Battery…4 guns

5th Brigade: Major General von Borstell

- 1st Pomeranian Infantry Regiment………………………….4 Battalions

- 2nd Prussian Reserve Infantry Regiment………………….3 Battalions

- Pomeranian Hussar Regiment………………………………..4 Squadrons

- 2nd Kurmark Landwehr Cavalry Regiment……………….4 Squadrons

- Swedish Morner Hussar Regiment…………………………..6 Squadrons

- Russian 44th Jager Regiment……………………………………2 Battalions

- Russian Izoum Hussar Regiment………………………………3 Squadrons

- Russian Converged Hussar Regiment………………………..3 Squadrons

- 10th Foot Artillery Battery…8 guns: Swedish Horse Artillery Battery…6 guns.

References

| ↑1 | Napoleon’s Marshals. Edited by David Chandler. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Leggiere. Michael V, Napoleon and the Struggle for Germany, page 356 -357. |

| ↑3 | Ibid, page 357 |

| ↑4 | Keefe. Major John M, Failure in Independent Tactical Command: Napoleon’s Marshals in 1813, page 33, Monograph published by the United States Army Command and Staff Collage. It is interesting that a similar situation arose regarding staff shortage when Ney arrived and took over command of almost half of Napoleon’s army during the Waterloo campaign of 1815, see later comments in the main text. |

| ↑5 | The American military historian, Theodore A. Dodge, considers Ney at fault for following Napoleon’s instructions to the letter. See, Keefe. Major John M, Failure in Independent Tactical Command: Napoleon’s Marshals in 1813, page 33. |

| ↑6 | See OOB below |

| ↑7 | Petre. F Loraine, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page 272. |

| ↑8 | Petre. F Lorraine, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page 272. |

| ↑9 | Petre. F. Lorraine, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page 272. |

| ↑10 | Keefe. Major John M, Failure in Independent Tactical Command: Napoleon’s Marshal’s in 1813, page 36. |

| ↑11 | Petre. F. Loraine, Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, page 275.

Casualties on the French side amounted to 22,000 of which some 13,000 were taken prisoner. They also lost over fifty cannon, four eagles and 400 wagons. Ney’s army was totally shattered and became even more demoralized than Macdonald’s after the battle on the Katzbach. Napoleon, upon hearing of the disaster is reported by Marshal Saint – Cyr as receiving the news “with all the coolness he could have brought to a discussion of events in China….”[12] Which begs the question, did he realise that he had let Ney down? The Army of the North’s losses amounted 10,500 killed and wounded mainly Prussian, the Swedish and Russian contingents, with the exception of their respective artillery, being only lightly engaged. The Prussian Landwehr had fought with courage and determination, their fighting spirit brought to the fore by Bülow and Tauentzien’s leadership. Pictures around the battlefield. https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/gun-positions-north-of-Dennewitz-looking-south-150x86.jpg 150w, https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/gun-positions-north-of-Dennewitz-looking-south-300x172.jpg 300w, https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/gun-positions-north-of-Dennewitz-looking-south-768x440.jpg 768w, https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/gun-positions-north-of-Dennewitz-looking-south-1024x587.jpg 1024w" width="250" height="143" loading="lazy" data-original-width="250" data-original-height="143" itemprop="http://schema.org/image" title="" alt="Gun positions north of Dennewitz looking south. Approximately the same view as painting by Alexander Wetterling." style="width: 250px; height: 143px;" /> https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/gun-positions-north-of-Dennewitz-looking-south-150x86.jpg 150w, https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/gun-positions-north-of-Dennewitz-looking-south-300x172.jpg 300w, https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/gun-positions-north-of-Dennewitz-looking-south-768x440.jpg 768w, https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/gun-positions-north-of-Dennewitz-looking-south-1024x587.jpg 1024w" width="250" height="143" loading="lazy" data-original-width="250" data-original-height="143" itemprop="http://schema.org/image" title="" alt="Gun positions north of Dennewitz looking south. Approximately the same view as painting by Alexander Wetterling." style="width: 250px; height: 143px;" /> Gun positions north of Dennewitz looking south. Approximately the same view as painting by Alexander Wetterling. For a full panoramic tour click here.

Bibliography.Brett-James. Anthony. Europe Against Napoleon: The Leipzig Campaign, 1813, From Eyewitness Accounts, London , 1970. Chandler. David G. The Campaigns of CNapoleon. London 1966 Chandler. David G. [Editor] Napoleon’s Marshals, London 1985 Elting, John and Vincent Esposito. A Military History Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars, New York, 1964. Fuller. Major– General J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol II, London 1963. Keefe. Major John M. Failure in Independent Tactical Command: Napleon’s Marshals in 1813, United States Army Command and Staff Collage, 2015. Leggiere. Michael V. Napoleon and the Struggle for Germany: The Franco – Prussian War of 1813, Vol II. Cambridge University Press 2015. Petre. F Lorraine. Napoleon’s Last Campaign in Germany 1813, Greenhill Books, 1992. Booklet in German, 1813 – 2013 Impressionen zum 200. Jahrestag des siegreihen Frühjahrsfeldzuges.

Order of Battle for the Army of BerlinCommanding General: Marshal Ney IV Corps: General of Division Bertrand 21,699 Infantry: 880 Cavalry: 64 Guns 12th Infantry Division (French): General of Division Morand

15th Division Infantry Division (Italian): General of Division Fontanelli

27th Infantry Division (Polish): General of Division Dabrowski

38th Infantry Division (Württemberg): General of Division Franquemont

VII Corps: General of Division Reynier 13,600 Infantry: 1,400 Cavalry: 41 Guns 24th Infantry Division (Saxon): General of Division Lecoq

25th Infantry Division: General of Division von Sahr

32nd Infantry Division (French with one Wurzburg Regiment and three batteries of Saxon artillery |

https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Windmill-in-south-of-Dennewitz-showing-slight-rise-in-the-land-looking-south.-150x113.jpg 150w,

https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Windmill-in-south-of-Dennewitz-showing-slight-rise-in-the-land-looking-south.-150x113.jpg 150w,  https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Bridge-in-Dennewitz-150x113.jpg 150w,

https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Bridge-in-Dennewitz-150x113.jpg 150w,  https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Monument-in-Dennewitz-by-Church-150x113.jpg 150w,

https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Monument-in-Dennewitz-by-Church-150x113.jpg 150w,  https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Church-in-Dennewitz-150x113.jpg 150w,

https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Church-in-Dennewitz-150x113.jpg 150w,

https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/River-at-Rohrbeck-looking-west.-150x113.jpg 150w,

https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/River-at-Rohrbeck-looking-west.-150x113.jpg 150w,  https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Seehausen-150x113.jpg 150w,

https://battlefieldanomalies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Seehausen-150x113.jpg 150w,

That is indeed the most detailed write up I have thus far received Sebastian!

I never thought much of Bernadotte as a military commander, although I do take your point concerning his term as monarch of Sweden and the peaceful outcome after the Napoleonic wars.

Many thanks for visiting the site.

Best Regards,

Graham

Wonderful write up! I cannot take issue with much.

Though, I think the characterization of Bernadotte as self-serving is too simplistic and once again falling into the trap of seeing a man through the lens of his enemies and not taking into account his responsibilities as a ruler (Carl Johan was by 1811 Regent). Like Napoleon, he had to make decisions that encompassed every aspect of his realm’s policies wherein military considerations were but just one aspect.

Bernadotte was under immense pressure politically, militarily and diplomatically and had to push Swedish interests amidst a coalition where all were pursuing their own national interests, and often at the expense of the smaller powers.

One must recall, that Sweden’s primary enemy in this War was Denmark (as usual) and that the treaties Sweden signed with Russia and Britain made it clear that Sweden’s primary goal was defeating the French as only as a prerequisite to taking the War to Denmark and to effect the cessation of Norway.

Sweden was still weak after the disasters of Gustav IV Adolf’s reign. Bernadotte had done much to bring the country back from economic ruin and rebuilt its armed forces. Frankly put, Sweden could not replace the 30,000 man Expeditionary Force fighting in Germany. And while the Prussians, Russians and Austrians had plenty of men, Bernadotte needed his 30K Swedes (and 25,000 Russians given to him by treaty) to see the War concluded against Denmark; particularly because Austria was doing everything in its power to succor Denmark and have Britain and Russia renege on its treaty promises regarding Denmark.

Bernadotte knew well enough this was going on and was in a diplomatic winner-take all duel with Metternich, and, as it turns out, Carl Johan was 100% correct to preserve as much as possible his Swedish Corps, and the Russian troops assigned to him for the duration of the War because Austria nearly accomplished its mission of saving Denmark. Without his troops Swedish and Russian troops following Leipzig he would not have been able to invade Denmark and knock them out of the War because Prussia reversed its policy and wanted Bernadotte to attack Denmark only when Napoleon was off the throne. Needless to say, only a fool would trust the major powers to honor its promises once they had no need of Sweden.

So, in the end, it isn’t so much as being self-serving: It was a ruler playing his hand as best he could in the midst of a tempest of coalition back-stabbing. Bernadotte’s plan was ultimately successful, and not just for Sweden. Removing Norway from Denmark was the first step in the latter’s growth toward full independence. By shearing Denmark of Norway, it removed once and for all Denmark’s pretences as a great power, leading them down a more peaceful path. And by defeating Denmark and reestablishing Sweden’s self-confidence, Bernadotte was able to focus on internal development and ween Sweden off dreams of imperial glory. The result is the most peaceful region in Europe; a huge departure from what had been the most warlike region.