Introduction.

Considering that it has now been one hundred years since the Japanese gave Imperial Russia such a mauling in the Russo-Japanese War, surprisingly little has been written concerning the anniversary of this, one of the most world shaping events in modern history. Not only was Russia humiliated in the eyes of her European neighbours, but also the outcome of the war itself was to transform the hitherto stereotype Western opinions of Asiatic complacency when challenged by the might of modern technology and imperialistic expansion.

The rise of Japanese imperialism can be traced back to the overthrow of the Shogunate in 1868, which restored power to the Emperor (Tenno or Mikado). Before this event Japan had endeavoured to pursue a policy of sublime isolation, which suppressed all contact with the West. This policy, however had been steadily eroded since American President Fillmore, after attempting to negotiate a treaty of friendship with Japan in 1853, and being refused, had then sent a naval squadron of seven ships which forced the signing of the treaty virtually at the mouth of the ships’ cannon. Thus trade with America was soon followed by demands from other nations such as Great Britain, Russia, Holland, France and Prussia for the same privileges. This in turn had caused Japan itself to consider its own expansionist policy. In 1894-1895, with a navy trained to a high standard by the British, and an army fully modernised along German lines, she fought a small but successful war against China, which secured Korea as part of the Mikado’s domains. Her other acquisitions from China, and in particular the Liaotung Peninsula in South Manchuria, which included Port Arthur, were soon wrenched from her grip by strong pressure from both France and Germany who had conspired with Russia for their return to Chinese control. Thereafter, in 1897, Russia, playing at diplomacy through the back door, undertook to pay off China’s war indemnity to Japan in return for concessions in South Manchuria. The result of these manoeuvres led to Russia, who desperately needed an ice free base for her navy, being allowed to build a continuation of its Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok across Manchuria, with yet another agreement for the building of a spur line down the Liaotung Peninsular that would connect with Port Arthur.

At this particular period Russia must have felt supremely confident in its achievements. She was now able to influence economic control over Manchuria, while the outside world was, to all intent and purpose, unable, or unwilling, to oppose her from at last having a warm seaport.

The Boxer (“Patriotic Harmonious Fists”) rising of 1900 had seen an international force, which included Russian and Japanese contingents, used in the relief of the foreign legations in Peking. The Japanese therefore had first hand knowledge of the problems Russia faced when attempting to deploy and supply a large army in the field in the Far East. Also, in 1902, the English, who like the Japanese after their war with China, had found themselves isolated owing to European condemnation for waging war on the Boers in South Africa, were only too happy to sign a defensive alliance with Japan. A condition of this treaty was that England would go to war with any country that joined Russia in a war against Japan. To add more weight to Japanese security, the American President, Theodore Roosevelt, gave a firm warning to France and Germany that any further bullying on their part towards Japan would result in America coming out firmly on her side.

Confronted by the proposition of having no allies, and the possibility of incurring the wrath of both America and Britain, The Tsar (Nicholas II) agreed to a staged withdrawal of his forces from Manchuria. By 1903 however this had been watered down with Russian troops still remaining ostensibly to guard their newly constructed railways, and also by the creation of the Russian Far East Timber Company which saw the potential of lucrative lumber concessions along the borders of Korea and China.

This proved to be the last straw for the Japanese, who now decided that further Russian duplicity and encroachments must be dealt with by armed intervention. In June 1903 the Emperor of Japan agreed to a war with Russia.

The Theatre of War.

The country over which the war was fought was rugged and mountainous although the plains and valleys were cultivated, the main crop consisting of millet could grow to the height of fifteen feet before harvesting. The roads were no more than dirt tracks, which became rutted and potholed in the stifling summers, and if not frozen solid, then covered in deep snow during the bitter cold winters. The whole countryside virtually disappeared under a sea of mud in the rainy season from July to September, and as the Russian Captain Soloviev wrote: “The mud reaches the breasts of the horses, covers the spokes of the wheels of heavy wagons sinking in the soil…Only Chinese arbas (high carts with huge wheels) survive the swamps and holes of the impassable Manchurian roads.”

For the Russians these problems were also compounded by the fact that the campaign was fought over 5,000 miles from Moscow. Their Trans-Siberian Railway was single track with hardly any facilities for off-loading or sidings on its entire route. It was not complete at two points, one at Lake Baikal where the loop line around the lake was still under construction, the other at The Great Kingan Mountains, where tunnelling was still not completed. These breaks on the line meant that to transport a regiment of troops from Moscow to Harbin would take from four to six weeks. When one adds to this the fact that Russian logistics in the form of feeding and supplying their armies had always been haphazard, it is small wonder that many of their soldiers arrived at their destination in very poor condition.

The determining factor for both sides was control of the sea. For the Japanese, naval supremacy was crucial, and as the main Russian Pacific Fleet was anchored in Port Arthur, it became imperative that this threat to any successful landing of their troops in Korea should be eliminated, while at the same time: “whether strategy demanded it or not, the conquest of Port Arthur was for Japan the spiritual pivot of the conflict.”

The Armies.

Russia had over 4,000,000 trained soldiers to Japans 800,000. However with the outbreak of war the Russians had no more than 130,000 men and 200 guns in Manchuria, while the Japanese could place their entire invading army of 283,000 men and 870 guns on the shores of Korea far more quickly than the Russians could be reinforced.

(note the white summer uniforms)

The main problem for the Tsarist government, which, in effect was the Tsar himself, was that all of the best regiments, such as the Guards and Grenadiers, had to be kept at home for fear of any unforeseen developments in Europe, and particularly any new revolt that might be contemplated by the Poles. There was also the growing unrest in the industrial cities, which was being fuelled by revolutionary agitation. But even with these factors taken into account there would still be well over a million men available for a war in Manchuria. Unfortunately the archaic and often brutal Tsarist regime even caused some of its own generals to question the dependability of its fighting men: “To maintain discipline in an army is almost impossible when the mass of the nation has no respect for authority, and when the authorities actually fear those under them.” As if to compound this fact, Russian reservists, rather than being amalgamated into the regular army, were formed into separate corps, which made them, as coherent fighting units, almost worthless.

Although the Japanese army was small and her financial situation incapable of sustaining a prolonged conflict she did have one great advantage over the might of the Romanov Empire, and that was her nationalistic and patriotic approach to the conflict. The Japanese were educated in their modern elementary schools to a high standard of respect and discipline, being taught that to serve in her armed forces was both heroic and in keeping with the traditions of the Samurai. Thus, in terms of morale, her troops were superior in their resolve to win the war and regain the territories humiliatingly snatched from them by Russia.

Both sides were armed with magazine rifles and breech loading rifled artillery. The machine-gun had now been developed into a formidable battlefield weapon, and the introduction of barbed wire added to the perils of any army attacking prepared positions. The only handicap that plagued both armies was their reliance on the bayonet, and on tactics that has proven outdated as far back as the Crimean War.

Sea Power.

Although the Russian navy had a numerical supremacy over Japan’s, the fact that her fleets were divided between the Baltic Sea, Black Sea and the Pacific Ocean meant that any concentration on their part would take a considerable time, while the Japanese had their entire fleet ready for immediate action.

The composition of both navies in the Far East is given below.

| Japan | Russia | |

| Battleships, 1st Class | 6 | 7 |

| Battleships, 2nd Class | 1 | 0 |

| Cruisers, 1st Class | 8 | 9 |

| Cruisers, 2nd Class | 12 | 0 |

| Cruisers, 3rd Class | 13 | 2 |

| Destroyers | 19 | 25 |

| Torpedo boats | 85 | 17 |

| Sloops and Gunboats | 16 | 12 |

Having no reserves to draw upon for her navy, as well as no construction facilities for fabricating her own warships, the Japanese fully realised that the Russian fleet at Port Arthur must be eliminated before Russia could send its Baltic fleet to its support. They also saw that to achieve this goal a land attack against the port itself would have to be undertaken in the event of the Russian fleet remaining under the protection of the harbour’s land batteries and forts. They also understood that although supremacy at sea was the key factor in the forthcoming war, Russia would never relinquish her hold on Manchuria unless she was also defeated decisively on land. Their plan of campaign was, however, based on the false premise that Port Arthur could be taken from the Russians as quickly as they had taken it from the Chinese in 1894.

The Commencement of Hostilities.

Without a formal declaration of war, on 5th February 1904, the Japanese Vice Admiral, Heihachiro Togo ordered 10 of his destroyers to attack the Russian fleet at Port Arthur, while on the following day he left the port of Sesebo with the First and Second Japanese fleets and made full steam for Port Arthur himself. On the night of February 8th Togo’s 10 advanced destroyers surprised two of their Russian counterparts who were patrolling outside the harbour, and thereafter a swarm of Japanese torpedo boats came dashing through the spray and darkness as their main fleet arrived on the scene, hitting the Russian ships before they had time to fully deploy their anti-torpedo nets or clear for action. The result was a shambles in which two Russian battleships and a cruiser were sunk in a matter of minutes, leaving the rest of the fleet in such confusion that it did not even manage to return fire. The following day the Russian fleet came out as if to seek a reckoning, but after engaging the Japanese for only forty indecisive minutes they returned to port. This, as General Fuller says: “vindicated Japan’s claim to be considered a first-class naval power and broke the spell of Russia’s naval supremacy.”

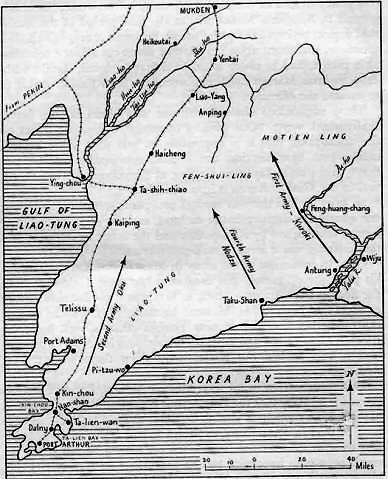

While Togo’ s fleet kept watch on Port Arthur, The Japanese put their land forces in motion, and a landing was made at Chempulo on 9th February by General Temetoko Kuroki’s 12th Division. After establishing a firm bridgehead, the 22nd Division and the Guards were landed, all three divisions being grouped together to form the Japanese 1st Army under Kuroki’s command. Soon after Pingyang and Anju were occupied, but the spring thaw caused further forward movement to become painfully slow. On 1st May the Battle of the Yalu River was fought, in which the Russians under General Zasulich were driven back. Although casualties on both sides were not great, its outcome proved to the rest of the world that Japan was a military force to be reckoned with. It also forced the Russian Commander-in Chief in Manchuria, General Alexie Nikolaevich Kuropatkin onto the defensive, a position from which he was unable to oppose the landing of the 2nd Japanese Army under General Baron Yasukata Oku on 5th May, as they came ashore on the Liaotung Peninsula, severing Kuropatkin’s communications with Port Arthur. This landing took the Russians by surprise, and the rapid advance of Oku’s divisions to seal off the peninsula was completed at the Battle of Nan-Shan (24th-26th May), where, despite a skilfully conducted defence by the Russian Colonel Tretyakov, the outnumbered defenders were forced to relinquish their position. Since the Japanese had now achieved the first part of their plan, the isolation of Port Arthur, without too much opposition, they persisted in their thinking that a swift attack on the port would cause its immediate surrender.

After their victory at Nan-Shan the Japanese were able to occupy the port of Dalny, where the docks were still intact. This facilitated the landing of their 11th Division, which, together with the First were now formed into the 3rd Army under the command of General Maresuke Nogi, with orders to advance directly down the peninsular against Port Arthur. While Nogi was making his drive on the port, General Oku moved to block the advance of a Russian relief force under General Stackelberg, which he defeated at Telissu on 15th June. Meanwhile Nogi had received additional reinforcements consisting of the Japanese 9th Division, which gave him an overall strength of between 80,000-90,000 men.

The Siege.

The Russian General in charge of the defence at Port Arthur was the incompetent and self opinionated Baron A. M. Stössel, who failed to relinquish his command to the more enterprising General Smirnov after being told to do so, and had exported tons of food from the beleaguered port which could have been used to sustain the population and the troops, leaving only a gigantic pile of packing cases which, upon inspection, proved to contain nothing but thousands of bottles of vodka! Now fully aware that the port was going to be besieged, Stössel issued an order stating that there would be no retreat; the fact that there was nowhere to retreat to does not seemed to have entered his head.

The Russian forces available for the defence of Port Arthur were not inconsiderable. Counting the crews of the Russian warships, Stössel had almost 50,000 men and over 500 guns. He could also, if circumstances dictated, remove guns from the fleet and use them to bolster his land defences. Altogether, counting non-combatants, the total population of the port was around 87,000.

The ports defensive system, at least at first glance, appeared formidable, being drawn up originally by the hero of the Crimean War, General Todleben. However many of the redoubts and forts were still unfinished, and the means for making concrete, together with material needed for reinforcing were in very short supply; barbed wire was also scarce.

The outer defence perimeter of Port Arthur consisted of a line of fortified hills, the most prominent among these being Hsiao-ku-Shan and Ta-ku-Shan near the Ta-ho River in the east, and Namako Yama, Akasaka Yama, 174 Meter Hill, 203 Meter Hill and False Hill in the west. At a distance of approximately one mile behind this first line ran the original Chinese wall, which encircled the Old Town of Port Arthur from the south, to the Lun-ho River at the northwest. The Russians had continued this line on again to the west and south, enclosing the approaches to the harbour and the New Town. These lines had also been strengthened by the addition of concrete forts and connecting trenches to facilitate the defence.

At some 4,000 meters to the rear again stood the last line of entrenchments surrounding the Old Town. However by the time this, “Last Ditch” could have been defended the port itself would have been untenable.

General Nogi, still confident that he could capture Port Arthur without too much trouble, began the bombardment of Ta-ku-Shan and Hsiao-ku-Shan on the 7th of August. After pounding the two fortified hills from 4.30 a.m. in the morning until 7.30 p.m. at night, he launched his infantry attack. Heavy rain, poor light and dense clouds of smoke slowed the Japanese assault, causing them to only get as far as the forward slopes of both hills. Undeterred, Nogi re-opened the bombardment the next day, this proved more effective and many of the Russian defenders fell back in some disorder. However there still remained a hard core of stalwart troops who hung on with great determination until they were finally overrun. Ta-ku-Shan was captured at 8.00 p.m., and the following morning, August 9th, Hsiao-ku-Shan also fell to the Japanese.

The loss of the two hills, when reported to the Russian Tsar, caused him to consider the safety of the fleet cooped-up in Port Arthur, and he sent immediate orders to Admiral Vitgeft, now in command of the fleet after the death of Admiral Marakov, to take to sea and join the squadron at Vladivostok. After receiving the Tsar’s message Vitgeft put to sea at 8.30 a.m. on the morning of 10th August with six battleships, three cruisers and eight destroyers, the cruiser Bayan being left behind owing to damage from a mine. Japanese destroyers spotted the Russian fleet at 11.30 a.m., and at 12.10 p.m. the first shots were fired in what was to become known as The Battle of the Yellow Sea.

The Japanese Admiral, Togo, had four battleships, eleven cruisers and an assortment of some forty-six other craft, including destroyers and torpedo boats. Not wishing to engage the enemy too closely, in case of sustaining heavy damage to his fleet which he knew he had to preserve in the event of the arrival of the Russian Baltic squadron, Togo chose to hold back his heavy battleships and cruisers, and rely on attacking the enemy fleet with his destroyers and torpedo boats. Noting that the Russian Admiral seemed to be trying to manoeuvre away from contact and seek to escape using the cover of night, Togo ordered his main armaments to close on the enemy fleet. At 4.15 p.m. a general action was brought on, and after one and a half hours of confused and constant shelling Vitgeft’s flagship, the Tsarevich was hit by a 12 inch shell, killing the Admiral outright. Thereafter the rest of the Russian fleet, owing to a total breakdown in their command structure, milled around in confusion. The Russian second in command, Prince Ukhtomski decided to try and make a run back to Port Arthur; however, the badly damaged Tsarevich, together with three destroyers made their escape to the Port of Kiao-chou, where they were interned, while three more Russian cruisers and a destroyer made it as far as Saigon and Shanghai respectively where they were also interned. Another cruiser, the Novik did manage to reach Russian territorial waters, only to be pounced upon by two Japanese cruisers near Sakhalin, and after a gallant fight her crew scuttled her.

The Battle of the Yellow Sea had one drawback as far as the lives of thousands of Japanese soldiers were concerned. It allowed General Nogi to instigate a plan for attacking Port Arthur before the arrival of the Russian Baltic fleet, which he considered he would be able to do by storming the fortifications at once. As General J.F.C.Fuller states, ‘Though such a decision is understandable, for this was the first attempt in history to storm a fortress held with magazine rifles, machine guns, and quick-firing artillery, there was little justification for General Nogi to suppose that it was likely to succeed against so determined an enemy as the Russians had proved themselves to be.’

After summoning the garrison of Port Arthur to surrender, which was promptly refused, the Japanese assault came at dawn on the 19th August, and was directed at 174 Meter Hill, with other storming parties going in along the line that ran from Fort Sung-shu to the Chi-Kuan Battery. 174 Meter Hill itself was held by two East Siberian regiments and two companies of sailors from the Russian fleet under the command of Colonel Tretyakov, the same man who had shown his ability at Nanshan. The fighting was desperate, being mostly carried out at night, and some idea of its intensity and confusion can be understood when reading the correspondence of Frederick Villiers the English observer with the Japanese 3rd Army, “…Three of the nine searchlights that the Russians appear to possess are playing incessantly on this section of the battlefield, and star bombs or rockets are bursting continually, their incandescent petals spreading fanlike and falling slowly to the ground. So brilliant are the lights that the moon, now nearing the horizon, is but a faint slip of silver in the sky. The colour of this night warfare is what Whistler would have revelled in. The deep purple of the mountains against the nocturnal blue, the pale lemon of the moon, the whitish rays of the searchlights, the warm incandescent glow of the star bombs, the reddish spurt from the cannon’s mouths, and the yellow flash from the exploding shell, all tempered to a mellowness by a thin haze of smoke, ever clinging to the hill-top and valley, make the scene the most weird and unique I have ever looked on during all the many wars I have witnessed.”

Just as he had done at Nanshan, Tretyakov, although having his first lines of trenches overrun, clung on with grim determination to 174 Meter Hill. The following day, 20th August, Tretyakov asked for reinforcements, and just as at Nanshan none were forthcoming. With more than half of his men either killed or wounded and the Japanese showing no slacking in their assaults, the rest of his command fell back in some confusion, which Tretyakov managed to control, but not before 174 Meter Hill was overrun. The cost had been high on both sides, with the Japanese having some 1,800 killed and wounded, and the Russians over 1,000.

The assaults on the other sections of the Russian line had also cost the Japanese dearly. When Nogi finally called off his attempt to take the port by storm on the 24th August, he had only 174 Meter Hill and West and East Pan-lung to show for his sacrifice of more than 16,000 men, all other positions remained firmly in Russian hands. Nogi at last decided that he must settle for a formal siege.

While the Japanese settled down in front of Port Arthur, the two belligerents’ main field armies had clashed at the Battle of Liaoyang. Here, on the 25th August, the day after Nogi’s last assault had failed, Marshal Oyama had engaged the Russians under Kuropatkin. The battle lasted for nine days and cost the Japanese over 20,000 men killed and wounded, and the Russians almost 18,000. The result was a Japanese victory, which had forced Kuropatkin to retire in order to cover his communications with Mukden.

Back at Port Arthur Nogi had now ordered the construction of trenches, and also the commencement of tunnelling operations under the walls of the Russian forts to permit mines to be planted to blow them up. He also now had the additional benefit of several fresh batteries of artillery and a reinforcement of 16,000 fresh troops from Japan, all of which compensated for the losses sustained in his first bloody assaults. He could also feel a measure of extra confidence with the news that he would soon be receiving some powerful Krupp 11-inch howitzer, also en route from Japan.

While the Japanese set to work with pickaxe and spade, General Stössel continued to play the buffoon. His mind was so taken up with trivia and social niceties that he spent most of his time writing complaining letters to the Tsar about the navy, which in turn made him a subject of ridicule among the Russian sailors, and all this at a time when the garrison and people in the port were running short of food, which was now beginning to take its toll in the form of serious outbreaks of scurvy and dysentery.

As Stössel glibly stared defeat in the face, Nogi pressed forward with his siege works. His plan now was to take the Temple and Waterworks Redoubts in the east, and 203 Meter Hill and Namako Yarma in the west. Geoffrey Dukes, in his work, The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905 makes the point that neither Nogi or Stössel seem to have realized the importance of 203 Meter Hill, as it commanded excellent views of the harbour, and, if taken by the Japanese, would enable them to bring down fire upon the Russian warships sheltering there. This fact was brought to Nogi’s attention when he was paid a visit by General Kodama, who immediately saw that the hill was the key to the whole Russian defence.

By mid September the Japanese had cut their trenches to within 70 meters of the Waterworks Redoubt, which they attacked and carried on the 19th, thereafter they successfully took and held the Temple Redoubt, while other strong attacking forces were sent against Namako Yama and 203 Meter Hill. The former was taken that same day, but the dense columns of troops sent against 203 Meter Hill were cut down in swathes and forced back leaving the ground covered in dead and wounded. After this the Russians now began to strengthen the hill still further, while Nogi settled down and began a prolonged artillery bombardment of the town and part of the harbour. However he did attempt yet another mass assault on the hill in October, which, if 203 Meter Hill had fallen, was to have been a ‘present’ for the Japanese emperor’s birthday. The only present the emperor received from Nogi was an increase in the casualty list after the attack once again foundered with the loss of almost 5,000 men.

As the defenders and civilians in Port Arthur were being subjected to bombardment and hunger, Kuropatkin had been receiving a stream of reinforcements for his main field army; these included two complete army corps. These troops had been acquired, in the main, by Kuropatkin’s falsification of his report concerning the battle of Liaoyang in which he had falsely claimed a victory. Unfortunately for the Russian commander this fresh acquisition of strength also came with orders to go onto the offensive once more and attempt to relieve the beleaguered town before it was forced to capitulate, thus freeing Nogi’s troops to join with the other Japanese armies in Manchuria.

The result was the battle of Sha-ho (7th-17th October), which once more proved a fiasco for Russian arms. Muddled orders and lack of proper communications resulted in the Tsar’s brave but disgracefully led battalions being slaughtered. The losses on the Russian side were 11,000 killed, and over 30,000 wounded. The Japanese losses were considerably lower, though still high, at 4,000 killed and 16,000 wounded. It must be remembered however that Russia could refill her ranks by drawing upon her massive reserve of manpower while the Japanese were without the benefit of this luxury. Once again Kuropatkin claimed a victory, and once again it seems that Nicholas believed him, but the truth of the matter was that whatever the Tsar or his commander in the field chose to believe, Port Arthur was now almost as good as doomed.

With the onset of winter both side’s main field armies settled into winter quarters. At Port Arthur Nogi had at last taken delivery of 18 of the Krupp 11- inch howitzers, which had been manhandled from the railhead by teams of 800 soldiers along an eight-mile narrow gauge track. These, together with another 450 guns as well as mortars now began to pound the Russian positions. The Japanese had centralised their artillery, which had its headquarters connected by miles of telephone lines with every battery along their front. The massive Krupp howitzers could throw a 227 kilo shell over 9,000 meters and during their period in front of Port Arthur over 35,000 of these “roaring trains” as they became known, were fired. In addition over 1,400,000 other types of shell were rained down on the port. As one Japanese officer wrote, ‘…with clockwork regularity, fantastic trees grew up every few minutes in different directions along the northeast front, and we heard the roars of dreadful explosions. Eight of them occurred in Erh-Lung-Shan and Chi-Kuan-Shan Forts this day (1st October) and did great damage to the casemates.’

Having no way of observing the effect of their fire on the Russian fleet in the harbour, and now well aware that the Russian Baltic fleet was on its way, the Japanese fully understood the necessity of destroying what ships were still serviceable in the port. To this end therefore it became essential that Nogi captured 203 Meter Hill.

Once again the Russians defenders dug-in on the hilltop were commanded by the intrepid Colonel Tretyakov, and consisted of five companies of infantry with machine gun detachments, a company of engineers, a few sailors and a battery of artillery. The hill itself, although having taken a terrible pounding during the previous attacks, was still formidable. As well as being of great natural strength, it was also well protected by a massive redoubt and two keeps, all of which was surrounded by thick wire entanglements. It was also connected to the two other forts on False Hill and Akasaka Yama by well dug lines of trenches and smaller field works.

After their costly attacks on the hill during October in which thousands of men had been killed and wounded, Nogi, under threat of replacement, now came under the orders of General Kodama who, although not replacing Nogi outright, nevertheless exercised strong pressure upon him to take drastic action, therefore Nogi saw no other option than to attempt one more all out assault upon the pock marked and blood soaked height. After weeks of tunnelling the Japanese sappers were now fighting to clear part of the underground defences, and on November 26th, the same day that the Russian Baltic fleet was entering the Indian Ocean, the Japanese commenced their attack on 203 Meter Hill.

The bombardment lasted until 5 p.m. on the 27th November, when, ‘The position resembled a volcano in eruption.’ Suddenly the guns fell silent as ant-like masses of Japanese troops poured out of their trenches and up the sides of the Akasaka Yarma and 203 Meter Hill. The attack was carried out in darkness enabling them to get up as far as the Russian line of wire entanglements. Here they held their ground throughout the following day, while their artillery redoubled its efforts to reduce the defences to rubble. The Japanese soldiers, ‘…fought like fiends, fought till they lost consciousness, one of their battalions being literally swept away from the face of the earth.’ The attackers managed to enter both forts, only to be driven out with appalling losses. The Russians rained down hand grenades into the seething mass of Japanese soldiers who poured into their forward trenches, while well positioned Russian machine guns mowed down hundreds more who were endeavouring to push forward, forcing them to relinquish their hold on the hills.

On the 30th November more assaults were carried out, and continued until the 4th December when it became so grim that one commentator noted, ‘…it was a struggle of human flesh against iron and steel, against blazing petroleum, lyddite, pyroxyline, and mélinite, and the stench of rotting corpses.’ But still the Russians held on.

Finally, at 10.30 a.m. on December 5th, after another terrific bombardment by their artillery, the Japanese managed to capture 203 Meter Hill, finding only a handful of dazed and bloody defenders still left alive. By 5.00 p.m., ‘…over the rubble on top of the hill the Rising Sun of Japan was seen flapping in the dusty air.’

Ellis Ashmead Bartlett, an eye witness to these events has left us a vivid and haunting description of the scene in his book, Port Arthur, The Siege and Capitulation, ‘This mountain would have been an ideal spot for a Peace Conference. There have probably never been so many dead crowded into so small a space since the French stormed the great redoubt at Borodino…The Japanese are horrible to look at when dead, for their complexion turns quite green, which gives them an unnatural appearance…There were practically no bodies intact; the hillside was carpeted with odd limbs, skulls, pieces of flesh, and the shapeless trunks of what had been once human beings, intermingled with pieces of shells, broken rifles, twisted bayonets, grenades, and masses of rock loosed from the surface by the explosions.’

The cost had indeed been great. Over 11,000 Japanese dead, and almost 10,000 wounded, which shows the severity of the fighting, and the fact that the Japanese literally fought to the death. The Russians lost over 6,000 in killed and wounded.

For Nogi the price was justified by the fact that he could now bombard the harbour and the Russian fleet by placing his heavy howitzers on the summit of 203 Meter Hill. This done he commenced to turn the Russian ships into scrap metal, leaving the way clear for Admiral Togo’s fleet to return to Japan for a refit, and then confront the Baltic Fleet with some chance of success.

Meanwhile in Port Arthur, Stössel held a council of war at which he was advised that the port could only hold out until the middle of January 1905. Choosing to disregard any opinion other than his own, Stössel decided that they should hold on until the very last. However at yet another council, on December 29th he was finally persuaded that surrender was now the only option, since the Japanese had by this time already captured part of the Chinese Wall, and were already preparing for a full-scale assault on the last Russian lines of defence. On January 1st 1905, Stössel sent a message to Nogi asking for terms of surrender, which were duly agreed and signed on January 2nd. With this the Russian garrison was taken into captivity, but civilians were allowed to leave, and Russian officers given the choice of either going with their men or giving their parole and taking no further part in the war. All told some 878 officers, 23,500 soldiers and 9,000 sailors, together with 14,000 sick and wounded surrendered to the Japanese.

Aftermath.

Now Kuropatkin had no other mandate than to hold onto what they still had in Manchuria, and to attempt to save as mush as possible of what remained of Russian dignity. He now had three armies under his overall command totalling 310,000 men, which were now pitted against the combined Japanese forces, including Nogi’s Third Army, of some 300,000. On February 23rd 1905 the great battle of Mukden opened along a 40-mile front, with both sides dug-in and supplied with hundreds of artillery pieces. The battle lasted until March 10th when strong Japanese pressure finally allowed them to cut the railway line to the north of Mukden. Now faced with the possibility of being surrounded Kuropatkin ordered a retreat, and fell back to cover his rail link with the town of Harbin. The cost of this, the greatest battle of the war was high. The Japanese lost over 15,000 killed and almost 60,000 wounded, the Russians lost 40,000 killed and captured, plus over 48,000 wounded.

The final act of the drama took place on 26th May, when the Japanese fleet under Admiral Togo attacked the Russian Baltic fleet, which had entered the China Sea on May 9th. The result was the Battle of Tsushima, and the destruction of the Russian fleet. These events in turn now brought about both sides considering sitting down at the peace negotiation table. On June 10th American President Theodore Roosevelt intervened and set up and oversaw the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth, which took place on 29th August 1905.

Two minor events took place, which were to have an impact far greater than was realised at the time. The first was in the form of an argument that took place on Mukden railway station between the future Russian army commanders Rennenkampf and Samsonov. It will probably never be known what caused them to become involved in a dispute that almost led to blows, but it must have been, at least to these two men, a matter of pride and honour. It was still simmering on at the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, and during the battle of Tannenburg could have had much to do with Rennenkampf’s dilatory behaviour when he failed to move rapidly to the support of Samsonov’s army which was about to be surrounded and destroyed.

The seconded incident occurred when Count Marusuke Nogi, the general who had captured Port Arthur, committed ritual suicide after the death of his emperor Meiji. This spectacular act of the old samurai warrior caused the old feudal beliefs and practices known as bushido (the way of the warrior) to become once more linked with the imperial house of Japan. Its effects were to prove disastrous for many young men, women and children during the Second World War, when they choose to sacrifice their lives for their emperor.

Graham J.Morris

January 2005

Bibliography.

| Bartlett, E.A. | Port Arthur: The Siege and Capitulation, London, 1906. |

| Fuller, General J.F.C. | The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol III, London, 1957. |

| Jukes, Geoffrey. | The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905, Paperback edition, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2002. |

| Martin, Peter. | The Chrysanthemum Throne, The History of the Emperors of Japan, England, 1997. |

| Nojine. E.K. | The Truth about Port Arthur (Translation), London, 1908.

See also, Official History (Naval and Military) of the Russo-Japanese War, prepared by the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence, London, 1910. |

| Sakuri, Tadayoshi, | Human Bullets, (Translation), London, 1907. |

Hi Brian,

Thanks for visiting the site and comments.

You should read Richard Connaughton’s book, “Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear” Russia’s War with Japan. A very well written account covering all aspects of the campaign. Also, on line, visit the Russo-Japanese War Society website; it has some of the lesser known details relating to the war>

Hope this will help?

Graham (battlefieldanomalies.com)

Great article, such an incredibly bloody siege

Also, what are some good sources for learning more about the details of the Russo-Japanese War? Specifically about the land campaign leading all the way up to the Battle of Mukden.