loading map - please wait...

The Battle of Kolin, 18th June 1757.

‘Ihr Racker, wollt ihr den ewig leben?’…

‘Fritze, fur acht Gorschen ist es heute genug!’

(‘Scoundrels, do you want to live forever?…

‘Fred, for eight pence we have done enough for today!’)

Frederick the Great chastising his troops for running away at the battle of Kolin and the reply he received from one of his grenadiers.

In the summer of 1756 Austria and France had joined in an alliance against Frederick the Great of Prussia. The Prussian King writing to his sister stated, ‘I am in a position of a traveller who sees himself surrounded by a bunch of rouges, who are planning to murder him and divide the spoils among themselves….I am waiting for a reply from the Queen of Hungary which will decide whether there is to be peace or war.’ [1]MacDonogh. Giles, Frederick the Great, page 255.

Frederick realised that if he was not to be overwhelmed by the gathering masses set against him he must strike first. Therefore by attacking Saxony he would not only gain space and a central base of operations, but also knock out one of Austria’s allies. On the 29th August 1756 Frederick invaded Saxony with an army of 62,000 men. The Saxon army of some 16,000 men and eighty cannon fell back inside the fortified camp at Pirna, abandoning Dresden, and were subsequently blockaded by the Prussians. However, the Saxon army did not have much in the way of supplies to sustain them for a prolonged period. Soon news began to arrive that the Austrian army under Field Marshal von Browne was in northern Bohemia and Frederick moved to join forces with Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick who commanded the right wing of his army there, leaving a containing force to watch the Saxons. On 1st October the battle of Lobositz was fought and although the Prussians held the field they had not managed to inflict any serious damage on the Austrian army, in fact, although the casualties on each side were about equal, 2,900 Austrian and 3,000 Prussian, the latter had suffered more men killed than the former and in the days following the battle the Prussians also lost many hundreds of men through desertion. [2]Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great. A Military History, page 143.

On October 17th hunger and low morale forced the Saxon army to surrender, Frederick at once incorporating the whole lot, in complete regiments, into the Prussian army, rather than splitting them up and distributing them throughout his own forces. Within two months most of the Saxon battalions had defected to the Austrians. As Dr Christopher Duffy stated, ‘…Perhaps he (Frederick) believed, like Prince Mortiz, that the Saxons would be eager to fight for a Protestant king. Perhaps he was led astray by his own crass indifference to the feelings which move the hearts of ordinary men, or perhaps he was blinded by his inveterate hatred of thing Saxon. Certainly there were times when Frederick seemed to be pursuing a private feud against the Saxons rather than a regular war.’ [3]Duffy. Christopher, The Army of Frederick the Great, page 169.

Whatever his feelings towards the Saxons were, by the beginning of 1757 Frederick had far more serious problems to deal with. In January Russia passed the convention of St Petersburg, which recognised the treaty between France and Austria, effectively joining the coalition against Prussia, while on 1st May 1757 the second Treaty of Versailles was signed in which France agreed to the partition of Prussia, undertaking to pay Austria an annual subsidy to keep a large army in the field against her. As compensation France would receive land in the Netherlands. [4]Millar. Simon, Kolin 1757. Frederick the Great’s first defeat, page 11. Writing to his sister in law Wilhelmina Frederick lamented, ‘The new triumvirate has outlawed me; Judas sold Christ for a mere thirty pieces of gold: the king of France has sold me to the queen of Hungary for five Flemish towns, I am therefore worth more than our Saviour.’ [5]Quoted in, MacDonogh. Giles, Frederick the Great, page, 254. Once again deciding to strike the first blow against the Austrians before the other members of the coalition had a chance to come to their aid, on April 18th 1757 Frederick’s army of 113,000 men crossed the Bohemian border in four separate columns on a wide front. The Austrian army was split up covering four areas of possible Prussian advance. Around the town of Königgrätz in the east 24,000 troops covered any approach from Silesia; while another 36,000 under Field Marshal von Browns direct command were stationed between Prague and the River Eger; a further 28,000 were around Regensburg watching the Lusatian boarder, and 24,000 more guarded the upper Eger. [6]Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great. A Military History, page 150. Unfortunately, on the 30th April, Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine took over the command of the Austrian army after the health of von Browne had seriously deteriorated, his appointment owing much to the fact that his brother was married to the Empress Maria Theresa who allowed him too much influence regarding military appointments. Charles’s lack of military talent soon became apparent.

On the 1st May Frederick was only 27 kilometres from Prague, his own column having now been joined by the forces under Prince Moritz of Dessau. The two other Prussian columns under Field Marshal von Schwerin and the Duke of Brunswick – Bevern were ordered to cross the River Elbe to the east of the city and cut off the Austrian army’s line of retreat. For their part the Austrians chose to leave a strong garrison in Prague, withdrawing the main body of their army, some 60,000 strong, east of the city on good defensive ground.

Fully realising that he could not attack the Austrians without first covering Prague to prevent the garrison there from moving on his rear, Frederick left 30,000 troops to watch the city and with 24,000 men and fifty cannon crossed the Moldau River to confront Charles; ordering Schwerin to join him immediately by forced march; on the 6th May Frederick had 64,000 men concentrated for battle. [7]Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great. A Military History, page 152 -153.

Frederick, feeling too sick to ride after eating a tainted pâté, saw immediately that a frontal assault on the strong Austrian position would end in failure and, at 7.00 a.m., decided to send Schwerin and General Winterfeldt marching south east to find an opening and attack the enemy’s right flank, but although they became well aware of the approach of the Prussian columns by the clouds of dust kicked up by thousands of men and horses, the Austrians still considered their position capable of withstanding anything that Frederick could throw against it.

Quickly moving troops to cover their right flank, the battle became a slogging match in which the Prussian infantry were thrown in piecemeal as they came on the field, suffering a series of bloody repulses in which Field Marshal Schwerin was killed attempting to rally his men. The Prussians fared better when their cavalry took on the Austrian horse in a mêlée of charges and counter charges. At a crucial stage of these engagements General Hans Joachim von Zieten, coming up with twenty – five squadrons of Prussian hussars hit the Austrian cavalry on their right flank, driving them from the field. [8]Duffy. Christopher,The Army of Frederick the Great, page 170

After the defeat of their cavalry on the right wing the Austrians now began to come under pressure on the opposite side of the field owing to their commitment on the other flank, which had caused an ever widening gap in their line into which Frederick poured eighteen fresh battalions. Catching the Austrians completely off balance, the Prussians pressed their attack driving the Austrians steadily back towards the gates of Prague. [9]Ibid, page 170 -171.

The battle of Prague had cost Frederick almost 14,000 men in killed and wounded while the Austrian losses numbered 13,500, but of these some 4,500 were prisoners. Not only were Prussian casualties greater than their enemy, but the death of Schwerin and other general officers, plus thousands of veteran infantry, made the victory a costly one.

For some reason Frederick became carried away with the notion that the capture of Prague would cause Maria Theresa to sue for peace, underestimating the resolve of the Austrian Empress and the capability of Austria to put together another army to send to its relief. Confident that a city of over 70,000 inhabitants now burdened with another 50,000 mouths to feed after the Austrian army had come within its walls would soon capitulate, Frederick settled down to blockade Prague.

Shocked by the news of the defeat, Maria Theresa quickly regained her composure and a new army was soon built up from recruits and the regiments that had not been engaged in the battle. The command of these units fell to Field Marshal Leopold Joseph von Daun, a methodical and careful leader, and by early June 55,000 men were concentrated in eastern Bohemia and preparing to march to relive Prague. Frederick, informed of the formation of a new Austrian army, at first treated the threat lightly, considering Daun a mediocre commander, and only detached the Duke of Bevern with 19,000 troops to keep an eye on him. On the 12th June Daun began advancing east and Bevern was soon sending urgent messages to Frederick for reinforcements. [10]Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great. A Military History, page 158.

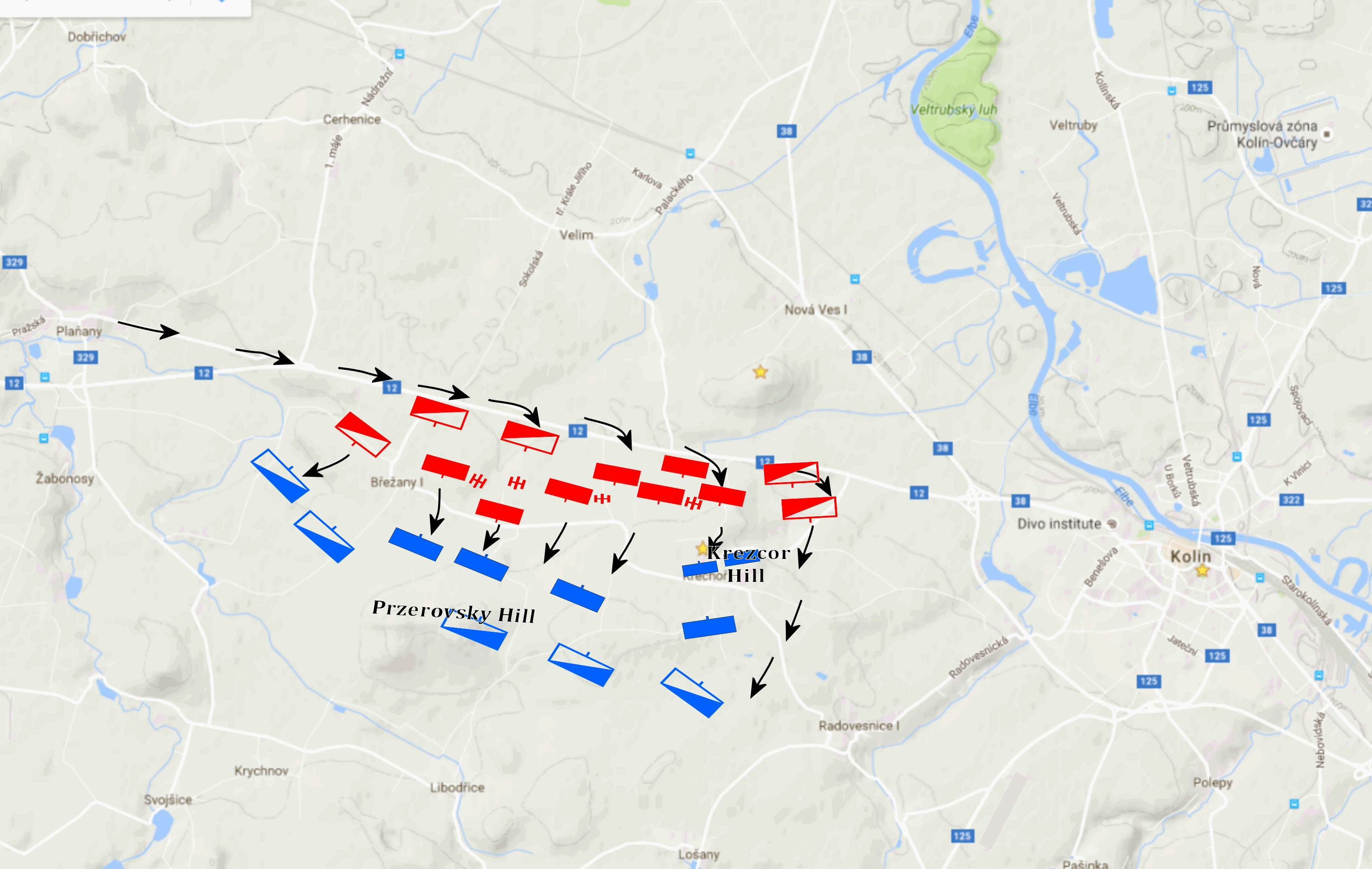

Now taking the threat of Daun’s advance seriously, Frederick joined Bevern with the main Prussian army, numbering altogether 35,000 men, leaving a containing force to cover Prague. At dawn on the 18th June Frederick discovered the Austrians drawn up on a range of low hills running south of the main road (Kaiserstrasse) close to the town of Kolin.

The Battlefield.

The main road or Kaisertrasse runs across the northern part of the battlefield and was used by the Prussians as they deployed for battle. About one and a half kilometres to the south of the road a low set of ridges stretching from just outside of the village of Poborz in the west to Krezecor in the east, and called Przerovsky Hill (west) and Krezcor Hill ( east) were occupied by the Austrians. The approaches to this formidable position were over open ground covered in crops and fully exposed to artillery and musket fire. In addition, the Austrian left flank was dotted with small lakes and ponds, making any coordinated attack in this area extremely difficult. To add to the positions natural strength, the whole terrain was well known to the Austrian high command, army manoeuvres having been carried out all across the site in 1756, a definite advantage over Frederick who had to constantly climb up and down buildings to try and get a view of the Austrian position and make his plans in accordance to what he could, or could not see. [11]Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great. A Military History, page 159.

On the outskirts of Krzeczor village to the north – west stood the old Swedish earthworks constructed during the Thirty Years War, its ramparts over fifteen feet high and enclosing several hectares. Also the ground to the right rear of the village was covered by an oak wood, the land rising towards the village being quite steep and cut up by a deep ravine.

The Austrian monument inside the old Swedish earthworks looking towards the Prussian position.

The Battle.

Frederick decided to adopt the same tactics that he had used at Prague and march across the Austrian front to attack their right wing, which he considered from his hasty inspection of the battlefield, was ideally suited to being outflanked and their whole position rolled up. To this end he ordered Major – General Johann von Hülsen to lead the advance guard of seven battalions to attack the Austrian right flank, to be followed in close support by nine battalions commanded by Major – General Joachim von Tresckow, the whole turning manoeuvre being accompanied by regiments of cuirassiers, dragoons and hussars who moved with the infantry ready to capitalise on events. The remainder of the army was to take up a ‘refused’ position. [12]Duffy. Christopher, The Army of Frederick the Great, page 171.

Frederick’s tactic of the “oblique order” was only in its formative stages of development at the battles of Prague and Kolin, it saw its greatest achievement at Leuthen on December 5th 1757. Its whole conception was based on the notion that the enemy would sit tight and allow the Prussians to approach their position; however, because cadence and a strict discipline were required in order for the whole system to work, an enemy that was aware of the Prussian approach could quickly counter the threat making the whole manoeuvre highly dubious.

At 1.30 p.m. on the hot afternoon of the 18th June Field Marshal Daun, was standing with his staff on the high ground midway between the Prezerovsky and the Krzecor hills watching the commencement of the Prussian advance and immediately called a council of war. Asking the opinion of Major Franz Vettez, who’s opinion Daun appreciated, he was informed that the Prussians would in all probability try to outflank the Austrian position by attacking towards Krzecor. Taking this advice seriously Daun ordered Lieutenant – General Heinrich Karl Wied’s division from its reserve position on the left to take post in rear of Lieutenant – General Johann Winulp von Starhemberg’s division on the Przerovsky Hill. [13]Millar. Simon, Kolin 1757. Frederick the Great’s first defeat, page 53.

The Prussians were indeed on the move, but their complex order of march caused Hülsen’s advance guard to take over an hour to get into position and when they finally did, at 2.00 p.m., under a scorching hot sun, they were greeted by a warm fire from Croat light infantry ensconced in Krzecor village. Pressing on with shouldered arms and bands playing Hülsen’s troops closed on the village aided by three battalions of grenadiers sent to their support by Frederick ,who now began to realise that he may well have underestimated both the enemies strength and the quality of its commander. Pushing on into Krzecor the Prussians suffered heavy losses from the concentrated fire of the Austrian artillery and as they cleared the now burning village and began to climb the ridge behind they were received by a murderous fire delivered by six regiments of Austrian infantry who had been brought forward by Daun from his reserve in the nick of time. [14]Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great: A Military History, page 160.

While Hulsen’s troops were toiling and sweating in an attempt to reform on the outskirts of Krzecor village, Frederick, altering his original plan, sent Major – General Joachim Christian von Tresckow with seven battalions, plus another detached from Infantry Regiment No 3 (Anhalt – Dessau) to advance and make contact with Hulsen’s right wing, this causing the Austrian light troops, who were harassing Hulsen’s command with a steady skirmishing fire, to slowly fall back through the standing crops, but still managing to turn occasionally and deliver a pestering peppering fire into Tresckow’s ranks.

It was now 3.30 p.m. and despite Prussian pressure Daune had managed to shuffle 15 battalions and much of his heavy artillery over to his right flank. More troops were on the way in the form of 7 battalions and 2 regiments of cavalry under Lieutenant – General Heinrich Karl Wied. For his part Frederick was now fully aware that he was up against a powerful and, although loathe to admit it, resourceful foe. Changing his mind again, Frederick now instructed his remaining infantry to move towards a small oak wood situated behind the village of Krzeczor, which he considered marked the position of the Austrian right flank. However, Frederick was impatient, and rather than moving to outflank the Austrians, his orders were to move directly on their objective. Commanding this advance was Prince Moritz of Dessau, who thought that he was intended to move around the enemy flank, and became concerned when suddenly his battalions, rather than forming into column of march, suddenly shook themselves out into line of battle and began to climb the slope of the Krzeczor hill, ‘…into the teeth of the main Austrian position!’ [15]Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great: A Military History, page. 160.

Showalter states that:

Frederick was thinking more deeply than his subordinate (Prince Moritz) realized. The King’s decision (to attempt to attack the Austrian right flank) was probably motivated by dust clouds – clouds suggesting a further shift of Austrian reserves eastward, towards Hülsen’s sector. The earlier brief doubts about the actual size of the Austrian army might well have been consciously suppressed as a manifestation of anxiety – particularly in the context of Frederick’s behaviour at Lobositz (where he had quit the field in panic). Instead, the King seems to have been taken by the idea that it was now possible to sweep over the Krzeczhorz (sic) ridge – a relatively low elevation – on a broad front against a weakened enemy. Move quickly and the Austrians might even be caught in march formation, before they had time to deploy against Hülsen. This point probably explains Frederick’s rage at Moritz, whose lack of comprehension threatened the entire plan. [16]Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great: A Military History, page 161.

Moritz was a good troop leader but, like the rest of Frederick’s subordinate commanders, not allowed any freedom of tactical thought. Moritz in all probability had also seen the dust cloud, and realised that the enemy was moving more reinforcements towards his right, but considered it better to continue with the proposed flank attack rather than committing his battalions to a frontal assault. After attempting to try to persuade his monarch to alter his plans three times, Moritz was finally told in no uncertain terms to obey orders and road away shaking his head and complaining, ‘and now the battle is lost.’ [17]Millar. Simon, Kolin 1757: Frederick the Great’s first defeat, page 57. What should have been a supple flanking manoeuvre had become a frontal attack against a foe who were now well prepared in both numbers and guns to meet it.

As Lieutenant Christian von Prittwitz recorded:

…we began to feel the effect of the enemy artillery… A storm of shot and howitzer shells passed clear over our heads, but more than enough fell in the ranks to smash a large number of our men… I glanced aside just once and saw an NCO torn apart by a shell nearby: the sight was frightful enough to take away my curiosity… we had to wind our way through the long corn, which reached as far as our necks, and as we came nearer we were greeted with a hail of canister that stretched whole clumps of our troops on the ground. We still had our muskets on the shoulders, and I could hear how the canister balls clattered against our bayonets. [18]Quoted in, Duffy. Christopher, The Army of Frederick the Great, page 172.

As Moritz’s battalions were attempting to climb the hill through this storm of metal, Major – General von Manstein, whose task it was to support Moritz’s attack, now (according to one source) took matters into his own hands and launched an unauthorized attack against the Austrian position, becoming so embroiled in a bitter exchange of fire that Frederick, much to his chagrin, had to order his final infantry reserve to support him. This account has, however, been questioned, and a more creditable account tells of one of Frederick’s aides – de – camp’s passing on a royal order for Manstein to clear enemy light troops who were harassing Moritz’s flank. Whatever the cause it does indeed seem that Manstein’s decision was not questioned or countermanded by the king, indeed it is very probable that, grasping at any opportunity to break the Austrian line, Frederick was willing to try anything. [19]Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great: A Military History, page 162. Despite their heroic commitment the Prussian infantry had, by 4 .00 p.m., been forced to form a weak and demoralized straggling single line facing the enemy position, backed up by a few pieces of their heavy artillery now, at last, brought up in support. [20]Ibid, page 163.

At around 5:30 p.m. Prussian cavalry came into action to bolster their flagging and heat exhausted infantry. These 20 squadrons were commanded by General von Pennavaire, who had acquired the nickname of ‘The Anvil’ having been beaten so often. [21]Duffy. Christopher, The Army of Frederick the Great, page 172. Moving at a steady pace the massed ranks of the 3rd Leibregiment; 1st Krockow Regiment, 11th Lieb –Carabinier Regiment and the 12th Kyau Cuirassier Regiment moved through the crops towards the Krzeczor Hill, taking a severe racking from the Croat light troops firing from the banks of the sunken roads around the village of Chotzemitz, which emptied many saddles. Topping the rise Pennavaire ordered the charge, driving his mass of horseflesh and steel into the compact ranks of three Austrian Cuirassier regiments who came forward to meet the threat. Expecting the impact the Prussian troopers braced themselves, only to see the Austrian horse veer off and retire towards the rear of their position. It was not a supple ruse, made to uncover a hidden artillery battery, but a mistaken order for the Austrian cavalry to break off the engagement and retire. For a brief moment Pannavaire thought he would be able to rid himself of his embarrassing sobriquet, but not so. His horses were blown and their impetus gone, and when within fifteen meters of the Austrian line they could do no more than fire a half – hearted volley into the enemy ranks with their pistols, which in turn was answered by a crashing volley from two Austrian regiments which bought men and horses down in heaps. To add to their woes the Prussian cavalry, who were on the point of retiring, were now hit by wave after wave of Austrian horse, causing them to break back in the utmost disorder.[22]Millar. Simon, Kolin 1757: Frederick the Great’s first defeat, page 69.

As Penavaire’s shattered squadrons were bolting back Frederick now gathered all the available forces he could muster to the left of the Prussian position in order to drive into the gap in the Austrian line on Krzeczor ridge. After taking a punishing fire from the Austrian artillery, the Prussian infantry went heads down for the ridge and, at around 7:00 p.m., finally broke the Austrian infantry line; all seemed now set for a Prussian victory. Unfortunately, although the enemy line had been pierced, and their infantry on this sector of the field were in disarray and confusion, the Austrian cavalry, kept well under control, were brought back from their pursuit of Panaviare’s bolting squadrons and hit the Prussian battalions in the right flank and rear, while the blancs becs (bare cheeks) regiment de Ligne came up from the oak wood hitting the staggering Prussians on the left. With no reserve left to send to their assistance, Frederick, in desperation, attempted to rally a few detachments to charge an Austrian artillery battery. After advancing about fifty meters the king found himself alone, causing one of his aides to inquire, ‘Does your Majesty intend to take the battery by yourself?’ [23]Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great: A Military History, page 164.

‘By now the catastrophe was general. Nineteen battalions of the left wing and advance guard were being chopped up by the cavalry, and Manstein’s command decimated by the artillery. The cavalry of the left wing and reserve were in disorder, and Zieten, who had not been on his best form in this battle, was laid unconscious by a canister shot which struck him on the head.’ [24]Duffy. Christopher, The Army of Frederick the Great, page 172.

With the sun falling down to the horizon, casting its last rays over a battlefield covered with dead and wounded, many of the latter that were still able to crawl or stagger, endeavouring to slake their desperate thirst, the Prussians began to withdraw, not in a coherent manner, but in a steady flow of men and horses who were only too happy that the days killing was over. With no follow up by the Austrians Frederick was indeed lucky to have escaped total destruction at Kolin.

The losses were significant, especially when we consider that the Prussian army only numbered just over 30,000 at the commencement of the battle. Latest figures are estimated at over 14,000 Prussians killed, wounded, or captured. Austrian losses are considered as being some 9,000, of which close to 2,000 were either killed during the battle or died a few weeks later. Casualty figures, even with the best of research, can never be exact. Men sometimes died within days, weeks, months or even years after the battle, and these numbers are never included, only listed as wounded. Given the state of surgery during this period then the “actual” death toll was in all probability far higher.

The Battlefield Today.

The battlefield of Kolin today is remarkably untouched and one can get an excellent feel for the battle when walking its fields and wandering through its villages. Dr Bob and I visited the site in 2013, taking a day off from our research around the battlefield of Königgrätz (Hardec Králové). Simon Miller’s book, Kolin 1757:Frederick the Great’s first defeat, has a very good description of the battlefield which needs no elaboration on my part, and it is my hope that it will be complimented by Dr Bob’s fine panorama photographs accompanying this article.

Bibliography.

Duffy. Christopher, The Army of Frederick the Great, Purnell Book Service, London 1974.

MacDonogh. Giles, Frederick the Great, paperback edition, Phoenix Press, London 1999.

Millar. Simon, Kolin 1757:Frederick the Great’s first defeat, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2001.

Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great: A Militay History, Frontline Books, England, 2012.

References

| ↑1 | MacDonogh. Giles, Frederick the Great, page 255. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great. A Military History, page 143. |

| ↑3 | Duffy. Christopher, The Army of Frederick the Great, page 169. |

| ↑4 | Millar. Simon, Kolin 1757. Frederick the Great’s first defeat, page 11. |

| ↑5 | Quoted in, MacDonogh. Giles, Frederick the Great, page, 254. |

| ↑6 | Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great. A Military History, page 150. |

| ↑7 | Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great. A Military History, page 152 -153. |

| ↑8 | Duffy. Christopher,The Army of Frederick the Great, page 170 |

| ↑9 | Ibid, page 170 -171. |

| ↑10 | Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great. A Military History, page 158. |

| ↑11 | Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great. A Military History, page 159. |

| ↑12 | Duffy. Christopher, The Army of Frederick the Great, page 171. |

| ↑13 | Millar. Simon, Kolin 1757. Frederick the Great’s first defeat, page 53. |

| ↑14 | Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great: A Military History, page 160. |

| ↑15 | Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great: A Military History, page. 160. |

| ↑16 | Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great: A Military History, page 161. |

| ↑17 | Millar. Simon, Kolin 1757: Frederick the Great’s first defeat, page 57. |

| ↑18 | Quoted in, Duffy. Christopher, The Army of Frederick the Great, page 172. |

| ↑19 | Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great: A Military History, page 162. |

| ↑20 | Ibid, page 163. |

| ↑21 | Duffy. Christopher, The Army of Frederick the Great, page 172. |

| ↑22 | Millar. Simon, Kolin 1757: Frederick the Great’s first defeat, page 69. |

| ↑23 | Showalter. Dennis, Frederick the Great: A Military History, page 164. |

| ↑24 | Duffy. Christopher, The Army of Frederick the Great, page 172. |

Thanks for your comments Mike.

The Kolin battlefield is one of the best-preserved sites in Europe.

Like Ramillies it retains that special ambience and makes the visitor aware of the events that occurred over the terrain, in particular around the old Swedish military earthwork camp and the views across the battlefield from there.

Very best regards,

Graham (battlefieldanomalies.)

Great account of the battle! I was there in 2017 and I overlaid one of Frederick’s maps over Google Maps to help me follow the battle. Other than the switch from German names in 1757 to Czech names in 2017, the terrain and infrastructure had barely changed in 260 years.

Great work on your site!