June 16th 1815.

Introduction.

The Battle of Waterloo in 1815 has been dealt with so many times that one finds most of the information available becomes no more than repeating what is already known. Therefore I have restricted myself to only dealing with the battle of Ligny, and the events that took place that directly affected the outcome of this, the last of Napoleon’s victories.

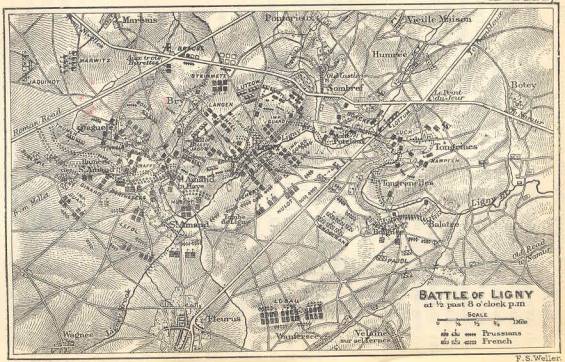

There is a description of the battlefield as it was when I visited it with my partner in 1982, plus photographs taken at the time, and a full list of the opposing forces both Prussian and French. I have also included maps of the battlefield as it was at the time of the battle, and modern road maps for those who feel more adventurous and would like to visit the site for themselves. Already, in 1982, much of the site was being developed and now, over twenty years on, parts of the field have become unrecognisable. Therefore I hope that all those who get a chance to visit what is left of these fields and villages, will take the opportunity to collect and record as much information as possible before this famous, precursor to defeat is lost forever.

Dispositions of the Opposing Forces, 14th June.

With the massive coalition of Russia, Austria, Prussia, Italy and England ranged against him in 1815, over 600,000 men, Napoleon had little choice other than attempting to knock one or two of his adversaries out of action before they could join forces and overwhelm him. To this end he decided to throw his weight against the nearest allied armies, those of the Prussians and Anglo-Dutch-Belgian. These two army groups were, in early June 1815, widely dispersed across Belgium. The Duke of Wellington, commanding the Allied army of 93,000 men was placed so as to protect the roads from Lille to Mons. The Prussian army of 117,000, commanded by Field Marshal Prince Blücher von Wahlstadt covered the Charleroi-Brussels main highway and the country to the east, their line of communications running through Liége. On the 14th of June the Allied armies were stationed as follows-

- Anglo-Dutch/Belgian 1st Corps under the Prince of Orange, Quatre-Bras to Enghien;

- 2nd Corps, Lord Hill, from Enghien to the River Scheldt;

- Reserve Corps, under Wellington himself, Brussels;

- Dutch-Belgian Cavalry on the River Sambre;

- Heavy Cavalry around Grammont-Ninove;

- Prussians, 1st Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General von Ziethen, Headquarters at Charleroi;

- 2nd Corps, Major General von Pirch I, Headquarters at Namur;

- 3rd Corps, Lieutenant General von Thielemann, Headquarters at Ciney;

- 4th Corps, General Count Bülow von Dennewitz, Headquarters at Liége.

As can be seen from the map, the town of Charleroi formed the connecting link between the Prussians and Anglo-Dutch/Belgian forces, It was here that Napoleon intended to strike his first blow, in the hope of separating the two allied armies from each other. This tactic had served him well on numerous occasions, and would allow him to deliver a crushing defeat upon one of his adversaries before turning against the other.

With great secrecy the various French Corps of the Armée du Nord were marched to their respective locations along the French-Belgian frontier. On the 14th June they were: – Left wing, I Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Count Drouet d’Erlon at Solre-sur-Sambre; II Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Count Reille at Leers; Centre, III Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Count Vandamme, and the VI Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Count Lobau, around Beaumont; Imperial Guard, commanded by Marshal Mortier, Duke of Treviso (not present with the army during the campaign), to the rear of Beaumont. Right wing, Reserve Cavalry, four corps, commanded by Marshal Count de Grouchy, between Beaumnot and Philippville; IV Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Count Gérard, approaching this wing from the direction of Metz. It can be seen from these dispositions that Napoleon had assembled his forces of almost 125,000 men within striking distance of his enemy’s advanced posts before Blücher and Wellington had been able to take any defensive measures:

‘Thus we get the rule that if the detached groups are nearer together than two full day’s march they can hardly be separately defeated, and a great risk is run of being caught between the enemy’s forces as they concentrate on the battlefield itself, thus bringing about the envelopment of the force in the central position…But supposing Blücher and Wellington did not fall back to concentrate on their own lines of communications, then their only other course was concentration on their inner flanks to oppose his (Napoleon’s) advance on Brussels. Napoleon, well served by his cavalry (sic) and by spies, was aware that Blücher could concentrate on his right 24 hours earlier than Wellington could on his left…Consequently Blücher might well be attacked and defeated before Wellington could complete concentration. It would appear, therefore, that an advance by the Charleroi-Brussels road afforded an excellent prospect of defeating the Allies in succession, whatever action they took.’ [1]Captain J.W.E. Donaldson and Captain A.F.Beck, Waterloo, page 17-18

With the exception of the left wing of the French army, which was to cross the River Sambre at Marchienne three miles to the west of Charleroi, all the remaining corps were to cross the bridge at Charleroi itself. Much has been said concerning the reason why Napoleon did not pass over the Sambre on a wider front, enveloping the I Prussian corps of general Ziethen before it could fall back to join the main body of the Prussian army. However, moving thousands of men and horses, as well as hundreds of cannon is not as simple as moving pieces on a chessboard, and Napoleon, once concentrated, saw no need to try to “bag” one Prussian corps when his intentions were to destroy their whole army. One of the most amazing things is that Ziethen, well knowing that the French were before him in great strength, did not destroy the bridges over the Sambre before falling back? Even allowing for the excellent work of French sappers and engineers, who would have been able to throw pontoons across the river, as well as working to repair the damaged bridges, the time consumed in these tasks would, in all probability, have allowed Blücher and Wellington to concentrate all their forces to meet the French advance.

The contempt Napoleon had for his enemies can be seen in the way in which he worded his “Order of the Day,” which I give here in full [2]Quoted in Sir Edward Creasy’s work, The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World, page 335 :

|

“Napoleon, by the Grace of God, and the Constitution of the Empire, Emperor of the French, &c. to the Grand Army. “ AT THE IMPERIAL HEAD-QUARTERS. Soldiers! This day is the anniversary of Marengo and Friedland, which twice decided the destiny of Europe. Then, as after Austerliz, as after Wagram, we were too generous! We believed in the protestations and in the oaths of princes, whom we left on their thrones. Now, however, leagued together, they aim at the independence and most sacred rights of France. They have commenced the most unjust aggressions. Let us, then, march to meet them. Are they and we no longer the same men? Soldiers! At Jena, against these same Prussians, now so arrogant, you were one to three, and at Montmirail one to six! Let those among you who have been captive to the English, describe the nature of their prison-ships, and the frightful miseries they endured. The Saxons, the Belgians, the Hanoverians, the soldiers of the Confederation of the Rhine, lament they are compelled to use their arms in the cause of princes, the enemies of justice and the rights of nations. They know that this coalition is insatiable! After having devoured twelve millions of Poles, twelve millions of Italians, one million Saxons, and six million Belgians, it now wishes to devour the states of the second rank of Germany. Madmen! One moment of prosperity has bewildered them. The oppression and the humiliation of the French people are beyond their power. If they enter France they will there find their grave. Soldiers! We have forced marches to make, battles to fight, dangers to encounter; but, with firmness victory will be ours. The rights, the honour, and the happiness of the country will be recovered! To every Frenchman who has a heart, the moment has now arrived to conquer or to die. Napoleon |

Movements and Dispositions, 15th June.

Duke of Dalmatia,

1769-1851

In the early hours of Tuesday, 15th June, with Napoleon’s words ringing in their ears, the French army began to move across the frontier, but things were not going smoothly with the execution of the Emperor’s plans. At 7.00 a.m. General of Division de Ghaisnes, Count of Bourmont, commander of the 14th Division of the French IV Army Corps (Gérard), deserted with all his staff to the Prussians. This threw his former division into a state of panic, which was only quietened down by the efforts of General Hulot, commander of one of the brigades, and by General Gérard himself who steadied the troops and restored their confidence. The news soon spread to old Blücher at his headquarters at Namur, but he made no change to his orders, even allowing for the fact that he was now fully aware that Napoleon had gained the initiative. [3]John Naylor, Waterloo, page 64 Instead he mounted his horse and set-off to join his army, which he had ordered to concentrate at Sombreffe.

Another glitch in the smooth advance of the French army had occurred at the centre where the III Corps, which should have been on the move at 3 a.m. did not receive their marching instructions until between four and five o’clock in the morning. It is said that the aide-de-camp carrying Napoleon’s orders to General Vandamme had fallen from his horse and broken his leg, thus the orders were not delivered. The consequences of this caused a bottleneck, as the troops who were to follow the III Corps had to be given new marching orders while Vandamme attempted to get his men on the road. [4]Edith Saunders, The Hundred Days, page 113 Napoleon sent for General Duhesme with the Young Guard to secure Charleroi and its bridge, and these troops, together with the sappers and marines gradually forced the Prussians to retire, the French taking possession of the town at around 12.00 a.m. [5]Commandant Henry Lachouque informs us that the Emperor occupied the house of M. Puissant. This became ‘the palace.’ The house was (is?) at the lower end of the town of Charleroi, on the right … Continue reading

The bridge over the Sambre at Marchienne, although being stoutly barricaded by the Prussians was cleared just after 10.30 a.m. by elements of Reille’s corps which crossed over the river closely followed by d’Erlon’s I corps, the Prussians falling back towards Gilly and Fleurus, retiring north-eastwards. This left one of Ziethen’s brigades under General Steinmetez isolated on their right flank, near Binche. These troops were hastily pulled back towards Gosselies. Meanwhile, General Pirch II Prussian brigade took up a defensive position at Gilly.

During these movements Marshal Ney, who had been summoned to join the French army, finally managed to procure horses for himself and his Aide-de-Camp Colonel Heymes, and joined Napoleon at Charleroi at around 3.00 p.m. Although undoubtedly still dubious of Ney’s behaviour during his return from Elba, when the marshal had promised King Louis XVIII that he would bring him back to Paris in an iron cage, Napoleon greeted Ney in a friendly way and gave him the command of the Ist and II nd corps and the Guard light cavalry division of General Lefebvre-Desnouettes, with instructions to, “Go and pursue the enemy.” [6]General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II, page 500 General J.F.C. Fuller, in his work, ‘The Desisive Battles of the Western World,’ states that, ‘There can be little doubt that he must have said more than this, and, according to Gourgaud (one of Napoleon’s ADCs), he instructed him (Ney) to sweep the enemy off the Charleroi-Brussels Road and occupy Quatre-Bras. The probability of the last injunction is supported by the statement in the Bulletin of the 15th June that “The Emperor has given the command of the left to the Prince of Moskova, who this evening established his headquarters at Quatre-Chemins on the Brussels Road.” Though Ney did not do so, this statement indicates that Napoleon intended that he should.’ [7]Ibid, page 500. See also Fullers footnotes concerning sources. Commandant Lachouque however states that, ‘ …what could he (Napoleon) know of the significance of Quatre-Bras? When he crossed into Belgium on the 15th June there was a heavy mist everywhere. He knew that Wellington was in Brussels and that Blücher was at Namur. It would have been impossible for him to make an accurate assessment of the situation.’ [8]Commandant Henry Lachouque, Waterloo, page 70 The problem with Lachouque’s argument is that he seems to forget that Napoleon could read a map! Quatre-Bras was an important crossroads and the fact that the French Emperor could not see it owing to the weather was immaterial to his plan of confronting one enemy army while holding back the other. Thus the debate concerning Ney’s orders to occupy Quatre-Bras would seem to favour the fact that they followed the general principles of the Emperor’s overall plan of campaign.

While Ney made his way to take command of the left wing of the army, Marshal Grouchy arrived at Napoleon’s headquarters and was given command of the right wing, consisting of the III and IV Corps, together with the cavalry divisions of Pajol and Excelmans. With these he was ordered to drive the Prussians back towards Sombreffe. Grouchy, probably as much in the dark concerning the exact positions of his forces as Ney must have been, dithered around so much that, at 5.30 p.m. Napoleon, becoming uneasy in not hearing the sound of Grouchy’s cannon, galloped forward to prod him along. [9]General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, page 500 * Girard’s division remained separated form the II nd Corps, coming under the control of General Vandamme. This done, the majority of Ziethen’s Prussians were pushed back as far as Fleurus. Over on the left Ney had also driven a Prussian detachment out of Gosselies, but he then halted his forward movement. Possibly one of the only times in his life when he exercised prudence, Ney failed to seize the all-important crossroads at Quatre-Bras. Wellington had not sent a single man to meet the forward movement of the French, and even though Prince Bernard of Saxe-Weimer had taken it upon himself to place his Nassau brigade, soon to be reinforced by three more battalions sent by General Perponcher at the crossroads, a vigorous attack could have brushed these aside. However, we must remember that Ney had fought the English in Spain, and probably considered that the small force visible at Quatre-Bras was only a façade, and that the woods and folds of ground concealed far larger bodies of allied troops. Whatever Ney’s reasons for not attacking on the evening of the 15th may or may not have been, a great chance to deliver a crushing blow to Wellington and Blücher’s concentration had been missed.

The French army bivouacked for the night in an area of ten miles by ten. On the left Lefebvre-Desnouettes’s cavalry was around Frasnes, with Reille’s II Corps between that point and Gosselies. Girard’s division of that corps was at Wangenies, near Fleurus*, while d’Erlon’s I Corps was covering the ground from Marchienne to Gosselies. On the right Marshal Grouchy had Pajol’s and Exelmans’s cavalry divisions south of Fleurus, around Lambusart. The III Corps under Vandamme was between Charleroi and Fleurus, while Gérard’s IV Corps camped on both sides of the Sambre River at Châtelet. In the centre, under Napoleon’s direct orders, were the Guard around Charleroi and Gilly, and to their rear, but still not across the river, were Lobau’s VI Corps and the cavalry corps of Milhaud and Kellermann. [10]General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, page 500-501 Napoleon had indeed achieved his first objective. He had placed his forces so as to separate both of the allied armies. However he had no idea that Blücher was intending to gather his army and offer battle the very next day.

Ney’s Orders and Whereabouts.

After returning to his headquarters at 9 p.m., Napoleon retired to his bed, totally worn-out. He was awakened at midnight and informed that Marshal Ney had arrived to make his report. We only have one witness to what took place at this interview, and that comes from Colonel Heymés, who tells us, “The Emperor made him (Ney) stay to supper, gave him his orders” and “unfolded to him his project and his hopes for the day of the 16th…” [11]Ibid, page 501-502 Of this Fuller states, ‘Therefore, it goes without saying that Ney must have told the Emperor why he had not occupied Quatre-Bras, and that the latter must have instructed him to occupy it early on June 16th. This is common sense, for should Wellington come to the support of Blücher, it was vital to Napoleon’s project of dealing with one hostile army at a time that the Nivelles-Namur Road should be blocked. To assume otherwise is to write Napoleon down as a strategic dunce.’ [12]Ibid, page 502

All of this is of course very true. The problem is:

- Was Colonel Heymés present at the interview?

- If not, did Ney inform him of what was said (one would have thought so being his ADC)?

- Did this meeting ever take place?

Baron Fain, Napoleon’s chief secretary wrote to Prince Joseph Bonaparte on the night of the 15th:

Monseigneur, it is nine in the evening. The Emperor, who has been on his horse since three this morning, has returned, exhausted. He has thrown himself on his bed for a few hours’ rest. At midnight he will have to mount his horse again… [13]Quoted in Edith Saunders, The Hundred Days page 123-124

If Napoleon were intending to ride out again at midnight, why would he have summoned Ney to a meeting? Edith Saunders tells us that, ‘Late at night, Napoleon rose to take a meal and read the reports, which included one sent in from Marshal Ney.’ [14]Edith Saunders, The Hundred Days, page 124 Just what this report contained is a mystery. Possibly it was just a confirmation from Ney concerning his taking over command of the left wing, or it may have been a statement of his actions (or lack of) during the afternoon of the 15th June. Let us not forget that Ney already had his instructions concerning the occupation of the Quatre-Bras crossroads, given to him by Napoleon when they met previously that day. * Saunders goes on to say that even at 5 a.m. on the morning of the 16th, ‘…Ney was still without orders…Colonel Heymés was inspecting the regiments, noting their numbers and the names of the commanding officers. Count Reille’s troops were ready to march, and at about seven o’clock he went to ask Ney for his orders, but was told that Ney himself still awaited instructions from the Emperor. All Ney had so far received was a dispatch from Soult, informing him that Kellermann was being sent to Gosselies and asking for information about the enemy on his front and the positions of the 1st and 2nd Corps.’ [15]Ibid, page 128-129. Saunders source comes from, Documents Inédits, by J.M.Ney, page 26. Ney’s reply is timed 7 a.m. * For an account of Soult’s dispatch on the 17th June, see Appendix ** See the … Continue reading It seems strange that if Ney had been at a meeting with Napoleon from 12.00 a.m. until 2.00 a.m., he was still none the wiser as to what was required of him at 7 a.m. in the morning! Also there is the problem of where Ney spent the night of the 15th-16th June. Over the years, and with several visits to the site, I have been told of three locations said to have accommodated the French Marshal. If he was with his forward units then he must have been somewhere in the region of Frasnes, but other sources place him in Gosselies or Fleurus! ** Wherever, or whatever he was doing on the night of the 15th June still remains a subject of some speculation.

Wellington’s Lack of Haste.

It appears that the Duke of Wellington did not consider an offensive by Napoleon. [16]See, Sir Herbert Maxwell’s, The Life of Wellington, Vol. II, page 10. Quoted in J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, footnote 3, page 502 He seems to have dismissed the idea to such an extent that when the rumours of the French concentration reached him on the 13th June, and of Napoleon himself being at Maubeuge, ‘he took Lady Jane Lennox to Enghien for a cricket match and brought her back at night, apparently having gone for no other object but to amuse her.’ [17]Ibid, page 502 The Duke was to receive yet more news of French movements on the 14th, but still did nothing until 3 p.m. on the following day. [18]Ibid, page 502 This time it was not a rumour, but a definite report informing him that the Prussians were being attacked. He at last ordered a concentration of his divisions at their respective designated areas where they were to hold and be ready to move at a moments notice. It was only then that the Prince of Orange was told to collect his 2nd and 3rd Divisions at Nivelles. [19]See Lady Elizabeth Longford, Wellington, The Years of the Sword, page 499. Here one is informed, albeit unintentionally, how Wellington still lingered over his dinner, replying to toasts.

When a dispatch was received that evening from Marshal Blücher setting out the Prussian commander’s intention to make a stand with his army at Sombreffe, Wellington, instead of conforming to the Prussian plan and moving his army to their support, ordered the 3rd Division to move towards Nivelles; the 1st Division to Braine-le-Comte; the 2nd Division and the 4th Division and the cavalry to Enghien. By these orders the Duke’s army was concentrating away from the Prussians, and shows that he still considered that the French intended to make a turning movement towards Mons and Ath. There can be no doubt that the Duke had indeed been “ Humbugged” by Napoleon.

After sending out these orders Wellington made his way to the Duchess of Richmond’s ball, arriving just after 10 p.m. and remaining there until 2 a.m. in the morning. Only upon receipt of a report from General Dörnberg, who was at Mons, telling him that the French had moved on Charleroi with all their forces, and that there was no threat in the direction he anticipated, did Wellington then order, ‘the whole army to march on Quatre-Bras.’ [20]J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, page 503. In fact Wellington still retained some 17,000 troops at Hal, still believing that Napoleon would attempt to turn his flank. These … Continue reading

Manoeuvres before the Battles of Ligny and Quatre-Bras, 16th June.

Napoleon was on horseback at 4 a.m. on the morning of the 16th, and in good spirits, intending to reach Brussels as soon as possible. Of course he did not know of Wellington’s movements, but considered that in all probability the Anglo-Belgian Army would take ground in front of Brussels and make a stand. In this event he would push them back to Antwerp, along their lines of communication, causing them to be separated still further from their Prussian allies. Before this plan could be put into operation however, Napoleon had to be sure that Blücher could not come to their assistance. The Prussian corps of General Ziethen must therefore be driven back passed Gembloux, denying Blücher the use of the Namur-Wavre-Brussels road. [21]John Naylor, Waterloo, page 70 Unfortunately, at about 8 a.m., Napoleon received a note from Marshal Grouchy informing him that the Prussians were concentrating around Sombreffe. Not believing it possible that Blücher would make a stand so far forward, Napoleon mounted his horse and rode to Fleurus to see for himself. Here Ziethen had pulled back the four brigades of his corps and was covering the approaches to Sombreffe, his forces drawn up along high ground around the farm and windmill of Bussy, with units pushed forward occupying the villages of Brye, Saint-Amand and Ligny, through, and in front of which, the small Ligne stream meandered.

At 11 a.m., under a boiling sun, Napoleon arrived at Fleurus with his staff and escort. He immediately ordered his engineers to construct an observation platform by knocking out part of the roof of the Fleurus windmill, and climbed the ladder to survey the situation for himself. [22]Edith Saunders, The Hundred Days, page 135 Although he could only see the troops of Ziethen’s corps he was soon convinced that they were holding their position while awaiting the arrival of reinforcements. These could be part of Wellington’s army or the main body of the Prussians, possibly both, and it became apparent to Napoleon that they intended a forward concentration in order to unite against him. [23]J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, page 505 At the moment he only had Vandamme’s III Corps in position, facing Saint-Amand, and he was informed that Gérard’s IV Corps was still some way from the battlefield. Until these troops arrived he did not feel strong enough to commence an attack. [24]Ibid, page 505 * The Prussian Fourth Corps, under Bülow was too far away to take part in the battle. As the time slipped by the Prussian corps of Pirch I and Thielemann arrived and took up their positions on the field. * Never one to get fazed in a critical situation, Napoleon was more than happy to know that he would be able to deal a decisive blow to the Prussian army.

General Fuller tells us that Napoleon’s plan:

‘ – a truly brilliant one- was first to contain Bülcher’s left (Thielemann’s corps) with Pajol’s and Excelman’s cavalry, and secondly to annihilate his right and centre (Ziethen and Prich). The latter operation he intended to carry out by engaging the Prussian centre and right frontally, so as to compel Blücher to exhaust his reserves, and meanwhile to call in Ney from Quatre-Bras to fall upon the rear of Blücher’s right wing while the Guard smashed through his centre. By these means he expected to destroy two-thirds of Blücher’s army and compel the remaining third to fall back on Liége-that is, away from Wellington.’ [25]J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, page 505-506

It must be noted here that no mention is made of Lobau’s VI Corps, which was still at Charleroi. It hardly seems possible that Napoleon would not have sent orders early on the 16th for this corps to move up and take position around Fleurus, but no such orders have ever been found, and it would seem that the great man is guilty of neglecting one of his own maxims of not having all available troops massed on the battlefield. This blunder, more so than the many others that occurred during this brief campaign was, in all probability, the decisive factor in Napoleon’s defeat.

While the Emperor was conducting his reconnaissance of the Prussian position, Wellington had joined Blücher at his headquarters at the Bussy windmill, sometime around 1 a.m. The Duke had stated his displeasure in regard to the Prussian deployment, their battalions and squadrons being exposed in full view of the French batteries. Old Blücher was however quite content with his dispositions and, as he had told Sir Henry Hardinge, the English attaché, ‘The Prussian soldier will not stand in line.’ [26]Edith Saunders, The Hunderd Days, page 136 Wellington stayed for a while, assuring the Prussian commander that he would bring his forces across to attack the French left providing that he was not attacked himself. Thereafter he left Blücher and was riding back towards his own lines when he heard the muffled thump of gunfire coming from the direction of Quatre-Bras.

At 2 a.m., Marshal Ney had at last begun to advance against the crossroads, sending Count Reille’s divisions (16,000 men) forward in their normal dense attacking columns. Only Perponcher’s 2nd Dutch-Belgian Division was still holding the ground around Quatre-Bras, and soon the French division of General Bachelu began to develop a serious attack against this thinly held line. The farm of Piraumont was taken, while another French division under General Foy seized the Gemioncourt farm and outbuildings. By 3.p.m. Napoleon’s brother, Prince Jérôme Bonaparte’s division was making steady progress against Pierrepont farm, driving the defenders back into the Wood of Bossu on their right flank. As Wellington galloped back on the field the situation looked bleak, and it soon became apparent that his whole position was about to crumble.

With the timing of a Hollywood cowboy film, help suddenly arrived in the form of a Dutch-Belgian cavalry brigade, followed closely by the stalwart division of Sir Thomas Picton, in all some 8,000 men. This reasonably fresh injection of strength managed to stabilise the position, and even though he was still outnumbered by almost two to one, Wellington now felt confident that he could hold on until more of his army arrived.

Troop dispositions of the French and Prussian Armies.

Back at Ligny the heat of a summer afternoon had become oppressive. Across the rolling landscape covered in tall crops and dotted here and there with woods and orchards, a haze had begun to hang over the masses of troops and horses as they stood awaiting the signal to begin the battle. At 2 p.m., with Gérard’s Corps now deployed on the field, Napoleon ordered Soult to write a dispatch to Ney informing him that Grouchy was about to engage the Prussians at Sombreffe and that, “His Majesty’s intention is that you also will attack whatever force is in front of you, and after you have vigorously pushed it back, you will turn in our direction, so as to bring about the envelopment of that body of the enemy’s troops whom I have just mentioned. If the latter is overthrown first, then His Majesty will manoeuvre in your direction, so as to assist your operation in a similar way.” [27]Documents Inédits, duc d’Elchingen, No XIII, page 40

After sending the message to Ney, Napoleon said to General Gérard, “ it is possible that three hours hence the fate of the war may be decided. If Ney carries out his orders thoroughly, not a gun of the Prussian Army will get away: it is taken in the very act (prise en flagrant délit).” [28]J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, page 506 Napoleon was correct concerning his assumption that the events at Ligny would decide the fate of the war, however by not crushing the Prussians fate dealt Napoleon the losing hand.

The positions of the various Prussian and French forces were as follows: On the French left, facing the villages of Wagnelée and Hameau de Saint-Amand was General Girard’s division. On his right stretched the massed ranks of General Vandamme’s III Corps facing the village of Saint-Amand, and containing the divisions of Generals Lefol, Habert and Berthézène. Vandamme’s corps cavalry division under General Domon covered the extreme left of this line with pickets out as far as Villers-Perwin. On Vandamme’s right, Gérard’s IV Corps covered the ground facing the village of Ligny; his three divisions were massed from left to right-General Vichery’s, General Hulot’s, and General Pecheux’s. On Gérard’s right again, and covering the ground in front of the villages of Tongrenelles, Boignee and Balatre, Marshal Grouchy had spread-out the cavalry divisions of Generals Excelman and Pajol, together with a few battalions of infantry. These troops were all that protected the French right flank in the event of a Prussian strike on that part of the field. [29]See the battlefield description given in our 1982 visit to the site. Around Fleurus, and held back as a general reserve and mass of decision, the Imperial Guard and the heavy cavalry corps of General Milhaud. All of the above making a total of some 68,000 men and 204 guns. [30]There are many conflicting figures regarding the exact total of the French and Prussian armies at Ligny. I have taken a norm, using Siborne, Fuller and Saunders.

Facing the French, the Prussians were ranged as follows: General Thielemann’s III Corps, confronting the forces under Marshal Grouchy on Prussian left flank; Major General Hobe’s cavalry corps, east of Balatre covering the Namur Road; Colonel Kämpfen’s Brigade on the rising ground behind Tongrenelles, near the village of Tongrines, with a strong skirmish line pushed out to dispute the line of the Ligny brook; the Brigades of Colonels Luck, Borcke and Stülpnägel, massed in battalion columns on the line from Mont Potriaux, north-west to Sombreffe; General Ziethen’s I Corps, covering the approaches to the village of Ligny, Major General von Henckel’s brigade in, and around Ligny village. Lieutenant Colonel von Jagow’s brigade in close support to the rear of Henckel; Major General von Pirch II brigade formed en masse near the Bussy windmill and farm; Major General Steinmetz’s brigade occupying the villages of Saint-Amand, Saint-Amand La Haye, Saint-Amand le Hameau, and Wagnelée, with his reserves drawn-up on the rising ground above the Ligne stream; In reserve, and massed in toy soldier array stood Pirch I Prussian II Corps, its brigades under Major General’s von Kraft, von Brause, and von Bose formed between Sombreffe and Bry, with the cavalry divisions of Jurgass and Rohl in support. On their far right flank, and at right angles to their main line stood the brigade of Major General von Tippelskirch, facing Marbais. Blücher also stationed a division of cavalry under General von Röder near his headquarters at Bussy- we may be sure that an old hussar like Blücher was always awaiting the chance to dash into the fray! The total Prussian forces present on the field amounted to some 83,000 men with 224 guns.

Commencement of the Battle of Ligny.

As the church clocks struck the hour of 3 p.m. they were echoed by three deep reports from the French Imperial Guard artillery as, ‘Europeans were still in the habit of opening their battles with three beats as they opened theatrical performances.’ [31]Edith Saunders, The Hundred Days, page 139 While Grouchy’s cavalry made demonstrations against Thielemann’s Prussians on the French right, Vandamme sent in General Lefol’s division against the village of Saint Amand over on the left. Although Napoleon was no connoisseur of music, he nevertheless understood what effect it could have on morale, therefore each regiment had its own band which, using a prearranged program of marches would strike-up such rousing tunes as, Veillons au Salut de l’Empire, La Grenadier, and, Marche á Marengo. To the accompaniment of one of these martial airs, the French battalions, preceded by a swarm of skirmishers, moved through the tall corn in three columns. Lefol’s troops were greeted by the blast of cannon fire from the Prussian batteries along the ridge, and by a steady roll of musket fire from the three battalions of the 29th Regiment who were defending the village, which, after a stubborn resistance, were finally forced back by superior numbers. General Steinmetz, commanding the Prussian brigade at the rear of Saint Amand, now threw-in his 12th and 24th Prussian Regiments, which forced the French back and regained the village. While Lefol reorganised his division for another attack, the French and Prussian batteries redoubled their fire along the whole line, filling the little valley of the Linge stream in thick clouds of billowing smoke.

Vandamme now sent forward the fresh brigades of Generals Gengoult and Dupeyroux of Habert’s division to bolster Lefol’s attack. These fresh masses soon made their weight tell against the Prussian 12th and 24th Regiments who, together with the original three battalions who occupied the village, were hard pressed to maintain control of Saint Amand. Steinmetz, with only the 1st and 3rd battalions of Westphalian Landwehr remaining in reserve, threw these troops into the village in a desperate attempt to stabilise the situation. As they came forward their commanding officers were all killed or wounded in the space of a few minutes, the 3rd battalion in particular suffering crippling losses before it even entered the village. Steinmetz’s brigade was forced to retire to a position between Bry and Sombreffe leaving 46 officers and 2,300 men either dead, wounded or prisoners. [32]William Siborne, The Waterloo Campaign, page 216 The French now moved to consolidate their gains, moving cannon down and into Saint Amand to repel any Prussian counter attacks.

On Vandamme’s right, the IV French Corps of General Gérard advanced on the village of Ligny, whose defenders, under Generals Henkel and Jagow were well protected by stout walls and banked-up hedges, together with the support of artillery batteries on each flank. As the attacking columns of French closed on the village they were greeted by a murderous fire that caused them to stagger for a moment, before bracing themselves and continuing their advance. On the outskirts of the village the French endeavoured to force their way in by main force, but were eventually driven back, leaving the ground carpeted with dead and wounded. Nothing daunted the French battalion and regimental officers regrouped their men and advanced once more, only to meet the same fate as the previous attack. By now many of the houses were ablaze, and the dense smoke from both the artillery fire and the conflagration obscured the view of the cannoniers of both armies, causing them to pour-in shot and shell blindly in the hope of not hitting their own formations. Eventually the French made a two-pronged assault on the village, forcing their way into the centre and gaining control of the Churchyard, while another column pierced the defences at the lower end of the village. [33]Ibid, page 216 Amid falling masonry and burning timbers the Prussian and French infantry fought each other hand to hand, house to house, and street to street until the superior numbers of the attackers prevailed. Siborne has left us with a romantic and flowery picture of this particular part of the battle which is typical of the prose that was expected at that time:

‘The Battle, on this part of the Field, now presented an awfully grand and animating spectacle, and the hopes of both parties were raised to the highest state of excitement. Intermingled with the quick but irregular discharge of small arms throughout the whole extent of the Village, came forth alternately the cheering “En avant!” and the exulting “Vive l’Empereur!”as also the emphatic “Vorwärts!” and wild “Hourrah!” whilst the Batteries along the Heights, continuing their terrific roar, plunged destruction into the masses seen descending on either side to join in the desperate struggle in the valley, out of which there now arose, from the old Castle of Ligny, volumes of dark thick smoke, succeeded by brilliant flames, imparting additional sublimity to the scene.” [34]William Siborne, The Waterloo campaign, page 217

The French were not allowed time to establish themselves in the village before the Prussians once more advanced in their turn. The 4th Westphalian Landwehr under Major Count von Gröben, together with the 13th and 19th Infantry Regiments of Colonel Schütters Brigade cleared the French from the village and captured two cannon that had been abandoned as they withdrew. General von Jagows III Brigade now, ‘…made a change of front to its left, and approached the Village; the 3rd Battalions of both the 7th and 29th Regiments had been detached to the right, to protect the Foot Batteries Nos. 3 and 8, and to remain in reserve; the four remaining Battalions descended into the Village as reinforcements.’ [35]Ibid, page 217

Although forced to relinquish their hold on Ligny, the French still remained in possession of Saint Amand, but found it difficult to debouch from there owing to the mass batteries that Ziethen had ranged to cover the exits from the village. Napoleon now ordered General Girard’s division to attack Saint Amand la Haye, which would outflank the Prussian gun line and hinder any renewed attack on Saint Amand.

Girard’s two brigades, under Generals Devilliers and Piat, advanced in massed columns and soon cleared Saint Amand la Haye of its defenders. Seeing that this advance threatened his right flank, Blücher now sent in General Pirch II with his brigade to retake the village. At the same time the 1st battalion of the Prussian 6th Regiment was moved from its position near the Bussy windmill to fill the gap vacated by Pirch’s movement, while the 2nd battalion of the 23rd Regiment (Bose’s Eighth Brigade) were shuffled over to fill the space left by the 6th Regiment. [36]Ibid, page 218 Also noting that the French could not only attempt a direct attack via the villages of Saint Amand, and Saint Amand la Haye, but could now seriously threaten his communications with Wellington, Blücher decided to occupy the village of Wagnelé from where his troops could not only secure the afore mentioned connection with the Anglo-Belgian forces, but also deliver a flank attack on the French left. Now it was General Pirch I who commanded the Prussian II Corps who was directed to send his 5th Brigade, under General Tippelskirchen to take and hold Wagnelé together with the cavalry brigade of Colonel Sohr and the two Regiments of the 7th and 8th Uhlans of Colonel Marwitz (Thielemann’s Corps). The Seventh Brigade under General Brause (Pirch I Corps) was moved forward to occupy the ground vacated by Tippelskirchen’s movements. [37]William Siborne, The Waterloo Campaign, page 219 * See photographs of our 1982 visit to the battlefield. As can be seen by all this repositioning, the Prussian reserves were already being seriously thinned.

At 4 p.m. General Pirch II brigade attacked Saint Amand la Haye, but suffered severely from the French artillery fire, which tore great gaps in their ranks. Nothing daunted the survivors marched on, only to be riddled by the defenders musket fire as they entered the village. Being unable to penetrate any further than the central area of the village, and although being reinforced by the 1st battalion of the 6th Prussian Regiment, the attackers became stalled when they attempted a turning movement between the two villages, being confronted by a large manor/farmhouse* from which the French could not be ejected. [38]William Siborne, The Waterloo Campaign, page 219

Once more the Prussians were forced to retire, in some disorder, to their original position. The French jubilation of yet again forcing the Prussians to abandon the village was tempered by the loss of their divisional commander, General Girard, who fell mortally wounded during this engagement. Still old Blücher would not be denied, and he now ordered a renewed assault on Saint Amand la Haye to contain Girard’s division while he launched his attack on the village of Wagnelé.

While these events were unfolding, Napoleon, from his eyrie on the Fleurus windmill, observed that the Prussians did indeed seem determined to hold their position. At a little after 3.15 p.m. he instructed Marshal Soult to send Ney the following order:

‘Monsieur le maréchal,

I wrote to you an hour ago to say that the Emperor would be attacking the enemy at half past two in the position he has taken between the village of Saint-Amand and Brye. At this moment the engagement is very sharp. His Majesty orders me to say that you must manoeuvre immediately so as to hem in the enemy’s right and give him a good pounding in the rear. His army is lost if you act vigorously. The fate of France is in your hands. Do not hesitate an instant, therefore, to move as the Emperor orders, bearing on the heights of Brye and Saint-Amand so as to take part in a victory which may be decisive. The enemy has been caught flagrante delicto as he was seeking to join the English.

Duc de Dalmatie. [39]Quoted in Edith Saunders, The Hundred Days, page 141

Edith Saunders informs us that, ‘The register of the Chief-of- Staff (Soult) shows that this message was sent out at 3.15 p.m. A duplicate was sent at 3.30 p.m., and at 3.30 p.m. also a message was sent to Lobau ordering him to bring the VI Corps up to Fleurus. This was in answer to a message that had just come in from Lobau with news that Ney was faced with enemy forces numbering about 20,000 at Quatre-Bras. Realizing from this information that Ney might, after all, be unable to manoeuvre at will, Napoleon decided to call up the VI Corps which he would probably need.’ [40]Ibid, page 141

The mystery of the pencilled note that Napoleon was supposed to have sent to Marshal Ney, after sending the above 3.15 p.m. dispatch, in which the Emperor ordered Ney to send d’Erlon’s I Corps across to Ligny has puzzled historians, and caused endless speculation. Napoleon himself never mentioned any such written communication, either pencilled by himself which, given the state of his handwriting would have been almost illegible, or that he dictated the same to one of his ADCs. If Napoleon had just received information that Ney was heavily engaged at Quatre-Bras, then he would not have deprived him of a whole army corps. How and who actually ordered d’Erlon’s divisions to march on Ligny remains one of the enigmas of this campaign.

That morning d’Erlon’s Corps was concentrated around Jumet, Ney’s orders to move on Frasnes arrived at midday, but owing to Reille’s corps moving to their appointed position, d’Erlon was obliged to wait until these troops had cleared the road. At the commencement of the battle of Quatre-Bras, d’Erlon had only reached Gosselies. At 4 p.m. the General rode forward ahead of his troops to announce that his corps was about to arrive on the battlefield. It was during his absence that the famous pencilled note ordering the whole corps to change direction and march on Ligny arrived. The ADC who delivered these instructions convinced d’Erlon’s divisional commanders that the orders came directly from the Emperor himself, and forthwith the whole corps changed direction towards Villers Perwin. The bearer of the message now galloped after d’Erlon himself who was nearing Frasnes, and upon catching up with him showed him the note and informed him that his corps was moving towards Ligny. d’Erlon himself says that it was Labédoyère, one of Napoleons favourite ADCs who delivered the message, and if anyone could recognise a member of the Emperor’s staff it was d’Erlon. Thereafter the phantom messenger told d’Erlon that he would ride on and show Marshal Ney the note and explain Napoleon’s intentions, ‘and after that we hear no more of him. He vanishes from the scene.’ [41]Edith Saunders, The Hundred Days, page 143 * I can find no record of prisoners taken by either side, and one therefore assumes that for the most part it was indeed a fight to the death.

Back on the battlefield of Ligny the French and Prussians continued their attacks and counter attacks against the burning villages. The heat of the day coupled with the fires and smoke from burning buildings made the atmosphere within these confined spaces almost unbearable. Blackened with powder smoke and grime the soldiers of both sides fought each other with a savage determination, no quarter being asked or given. *

Blüchers preparations for a renewed attack on Saint Amand la Haye were now complete. At a little after 4.15 p.m. Pirch II once more advanced his battalions against the village, clearing it of the French at the point of the bayonet; Major Quadt commanding the 28th Regiment together with elements from Tippelskirchen’s brigade also forcing the enemy to relinquish their hold on the manor/farm buildings which had proved so much trouble to previous attacks. [42]William Siborne,The Waterloo Campaign, page 220

Simultaneous with this attack General Tippelskirchen launched a vigorous assault on Wagnelé. Although managing to occupy the village without too much opposition, when they endeavoured to debouch towards the French position they were assailed by a heavy fire from French infantry concealed amongst the tall corn. This caused such disorder within their ranks that the whole Prussian attacking force fell back to their original position at the rear of the village. Seeing that the Prussians were in a state of confusion after their retreat, the French now renewed their attack upon Saint Amand la Haye, moving columns of infantry on both flanks of the village, as well as attacking it directly from the front. Blücher bolstered the defence of the village by sending the 3rd Battalion of the 23rd Regiment from Colonel Langen’s Eighth Brigade, and soon after also sent in the 3rd Battalion of the 9th Regiment together with the three battalions of the 26th Regiment (all from General Krafft’s Sixth Brigade). These fresh troops allowed Pirch II to withdraw his shattered battalions to a reserve position near Bry, and managed to contain the French attack. [43]Ibid, page 223

Around Ligny, General Henkel’s Fourth Prussian Brigade supported by General Jagow’s (Third Brigade) still held the village and its approaches. A counter attack by the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 7th Regiment (Jagow’s Brigade) was ordered against the French who were once more preparing to advance. This resulted in both sides volleying each other at close range until still more battalions were pushed forward from Percheux’s French division which compelled the Prussians to fall back into the village. Here the fighting took on a new savagery with men lashing out with musket butts, cold steel and bear hands. As Siborne so graphically describes it:

‘The fight throughout the whole village of Ligny was now at the hottest: the place was literally crammed with combatants, and its streets and enclosures were choked up with the wounded, the dying, and the dead: every house that had escaped being set on fire, was the scene of a desperate struggle: the troops fought no longer in combined order, but in numerous and irregular groups, separated by houses either in flames, or held as little forts, sometimes by the one, and sometimes by the other party; and in various instances, when their ammunition failed, or when they found themselves suddenly assailed from different sides, the bayonet, and even the butt, supplied them with a ready means of prosecuting the dreadful carnage…The earth now trembled under the tremendous cannonade; and as the flames, issuing from the numerous burning houses intermingled with the dense volumes of smoke, shot directly upwards through the light grey mass which rendered the Village indistinguishable, and seemed continually to thicken, the scene resembled for a time some violent convulsion of nature, and rather than a human conflict- as if the valley had been rent asunder, and Ligny had become the focus of a burning crater.’ [44]William Siborne, The Waterloo Campaign, page 225-226

Eventually the French gained possession of the Churchyard, and consolidated their hold on it by bringing forward two pieces of artillery, which spewed canister amongst the ranks of the Prussian 7th Regiment, and the 1st Battalion of the 3rd Westphalian Landwehr (both of Jagow’s brigade). Try as they may to evict their antagonists, after a further three unsuccessful attempts, the Prussians finally withdrew to the outskirts of the village.

At just after 5 p.m., seeing the depletion of the Prussian reserves, and having kept an adequate mass of decision in hand for just such an eventuality, Napoleon now ordered the Imperial Guard, together with the cuirassier division of General Milhaud to break the Prussian centre. While these formations were making their way forward General Vandamme galloped across from the left wing bringing news that a massive enemy column was marching on Fleurus, and only some three miles away with the intent, it seemed, of turning the French left. Ney and d’Erlon had both been instructed that if they could join in the defeat of the Prussians, then they were to approach by way of Saint Amand. Vandamme was convinced that part of Wellington’s army had come across to succour the Prussians, and when an officer from his staff who had been sent to identify this new development came riding back shouting, “They are enemies, they are enemies!” the panic caused soon spread along the ranks like wild-fire. General Lefol’s division broke back in panic and Girard’s division (now commanded by Colonel Matis, the two other generals of brigade being wounded) was forced to abandon Saint Amand la Haye to meet the threat of a flank attack. Lefol turned his cannon on his own men to stop them fleeing the field. [45]Edith Saunders, The Hundred Days, page 148

Napoleon remained calm, but suspended the attack of the Guard while the situation was clarified. After sending one of his own ADC’s to investigate the mysterious column, he supported Vandamme’s wavering corps by dispatching the Young Guard under General Duhesme to the left wing. The aide sent by the Emperor returned after about one hour with news that the column was French, but that for some inexplicable reason it was now turning away from the battlefield!

These troops were, of course, d’Erlon’s divisions who had been obeying the instructions given by the mysterious ADC carrying the pencilled note. The reason for its approach march was, in all probability due to nothing more than a mix-up in place names. Since it has been assumed that d’Erlon was to make contact with the French left wing at Wagnelée, but was found to be bearing on Fleurus, the simple answer is that Wangenies, near Fleurus, had been mistaken for Wagnelée.

Poor d’Erlon was once more confronted with a dilemma. After coming within sight of the battlefield of Ligny he had received yet another order, this time from Marshal Ney, who in a fit of fury at being deprived of almost half his original force had, upon being informed that d’Erlon was marching towards the Ligny battlefield, sent an urgent message instructing the general to retrace his steps and return to Quatre-Bras. This order was not only to deprive Napoleon of a resounding victory over the Prussians, but is hard to justify because, with the distance involved, it would mean that d’Erlon’s troops could not possibly arrive back before nightfall. Also the fact that both Ney and d’Erlon were aware that the order to move the I Corps across to Ligny came from Napoleon himself, then it seems strange that both men chose to disobey a direct command from their Emperor? That there was indeed a state of uncertainty in d’Erlon’s mind is shown by the fact that before turning to march back towards Quatre-Bras, he dropped off Durutte’s division and his cavalry facing Wagnelée in case they would be needed.

Napoleon himself can also be blamed for the fact that, once knowing that the column was French, he did not send one of his ADC’s with explicit instructions for it to manoeuvre against the Prussian right flank. Thus the failure to bring Lobau’s corps onto the battlefield in time for it to play a decisive role in the defeat of the Prussians, coupled with the lack of precise instructions to d’Erlon when he was within striking distance of the enemy would seem to show that Napoleon had lost his grip on the situation, and that, in the final analysis it was his lack of firm control and judgement that cost him the crushing victory he so much required.

Time had past, and it was not until 7 p.m. that order had been restored on the French left. Vandamme, with the aid of the Young Guard units sent by Napoleon, had at last recovered his former position, while around Ligny the Prussians units were being reduced and exhausted by the constant fighting. The French had pummelled this section of the line to such an extent that now all that was required was an injection of fresh force, which would split it asunder. As dark masses of thunderclouds began to roll across the sky, the Imperial Guard artillery, together with the batteries posted along the front unleashed a terrible bombardment from over 200 cannon.

Now, at 7.45 p.m. to the accompaniment of peals of thunder and flashes of lightening the massed ranks of the Imperial Guard with cries of “Vive l’Empereur!” moved forward in a deluge of warm rain to the attack. As they descended into the little valley of the Linge stream the French batteries fell silent. Sweeping everything before them the Guard cleared Lingy with the bayonet, and was soon climbing the heights towards the Brye.

Blücher, who had been over on the Prussian right came galloping back only to find his centre shattered. Nevertheless the old hussar still had fight left in him. As the rain stopped and the setting sun pierced the gloom with its dying rays he called up General Röder’s 32 squadrons of cavalry and, placing himself at their head led them against the squares of the French Guard. [46]General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol II, page 509 Amid the chaos and confusion Blücher’s horse was shot, and as it fell pinned him to the ground so that he was unable to rise. Count Nostitz, one of his aides-de-camp tried unsuccessfully to free him as the Prussian cavalry was driven back by the Milhaud’s cuirassiers. These mounted giants, unable to recognize what a prize was within their grasp owing to the failing light, charged on past the Prussian commander, and were in their turn forced to retire by a spirited counter attack made by a regiment of Prussian Uhlans. After being passed twice by enemy cavalry, Blücher was at last freed and led to safety.

The Prussian centre had been completely smashed and was retiring in disorder, however the stubborn defence put up by the two wings of their army prevented it from becoming a rout. On the right General Ziethen slowly fell back behind Brye, managing to take most of his artillery off the field and showing a bold front to Vandamme’s weary divisions, while on the left General Thielemann retreated unharmed, Leaving a strong rearguard at Sombreffe. [47]Edith Saunders, The Hundred Days, page 152

The battle had cost the Prussians 16,000 in killed and wounded, together with the loss of twenty-one cannon, and during the night after the battle a further 8,000 men deserted their army. The French losses were between 11,000-12,000, and Girard’s division had been whittled down so much by casualties that it remained near Fleurus for the rest of the campaign.

Napoleon had his victory, but it was not a decisive one. His neglect in not calling up Lobau’s Corps earlier in the day, coupled with his failure to send direct orders to d’Erlon when that general’s troops were so close to the field, show a total lapse of his normal military principles. By not having all his forces gathered together on the main battlefield he wore-out what he had and ignored what was available. The fact that he divided his army once again after the battle of Ligny, sending 30,000 men to pursue what he considered to be a “ defeated foe”, admits to the fact that eventually oversights and blunders like these were bound to tell against him in the end.

Graham J Morris

May 2004

Appendix

Letter sent by Marshal Soult to Ney on the 17th June.

‘His Majesty was grieved to learn that you did not succeed yesterday; the divisions acted in isolation, and therefore sustained losses.

If the corps of Count Rellie and d’Erlon had been together, not a soldier of the English corps that came to attack you would have escaped; if Count d’Erlon had executed the movement on Saint-Amand ordered by the Emperor, the Prussian army would have been totally destroyed and we should perhaps have taken 30,000 prisoners.

The corps of General Vandamme and Gérard and the Imperial Guard were kept together all the time; one lays oneself open to reverses when detachments are jeopardized.

The Emperor hopes and desires that your seven divisions of infantry and cavalry will be well formed and united, occupying as a whole less than a league of territory, so that they are well in hand for use if necessary.’

From the above we can see that, even though Napoleon mentions the fact that, ‘if Count d’Erlon had executed the movement on Saint-Amand,’ this should not be taken in isolation. When the sentence is read as a whole it can be seen that Soult is simply discussing two possibilities. Concerning the movement on Saint-Amand, he is referring to the order dispatched at 3.15 p.m., not to the mysterious pencilled note, therefore it would appear that Napoleon was not expecting any aid from Ney if he became fully engaged with Wellington. (See Edith Saunders, The Hundred Days, page 303)

The Battlefield in 1982.

In April 1982 my partner and I visited the battlefield of Ligny, in the province of Hainault, Belgium. We managed to obtain a room at the Auberge du Marshal Ney, in Fleurus. Although we were told that the hotel was officially closed until May, the patron opened up a room and served dinner to us once he found out about our interest in the battle. The building itself was said to have been used by Marshal Ney on the night of the 15th June 1815, however there are another two or three habitations within four or five miles of Fleurus which also claimed the same distinction!

In April 1982 my partner and I visited the battlefield of Ligny, in the province of Hainault, Belgium. We managed to obtain a room at the Auberge du Marshal Ney, in Fleurus. Although we were told that the hotel was officially closed until May, the patron opened up a room and served dinner to us once he found out about our interest in the battle. The building itself was said to have been used by Marshal Ney on the night of the 15th June 1815, however there are another two or three habitations within four or five miles of Fleurus which also claimed the same distinction!

The town of Fleurus itself has played host to the armies of France many times in the past, from Luxembourg 1696, Jourdan 1794, to Napoleon in 1815. It is known locally as, ‘La Ville des Trois Victories Françaises.’ A brochure from 1958 gives details of the Festivals that took place here, including a, ‘Féte communales historique et Napoleon,’ but alas during our visit we were informed that these had ceased to occur. Maybe the good people of Fleurus once more celebrate the three victories of France considering the massive upsurge of enthusiasm for all things Napoleonic?

The ‘Moulin Naveau’ (windmill) is situated on the left hand side of the road leading out of Fleurus to Gembloux, and was used by Napoleon as an observatory during the battle of Ligny. At the time of our visit it was in very good condition, although whether or not the original windmill was made of brick is debateable, many paintings of the battle showing it to be a wooded structure? At the foot of the windmill is the monument celebrating the three French victories at Fleurus.

The ‘Moulin Naveau’ (windmill) is situated on the left hand side of the road leading out of Fleurus to Gembloux, and was used by Napoleon as an observatory during the battle of Ligny. At the time of our visit it was in very good condition, although whether or not the original windmill was made of brick is debateable, many paintings of the battle showing it to be a wooded structure? At the foot of the windmill is the monument celebrating the three French victories at Fleurus.

From here we drove to the Château de la Paix, which Napoleon used as his Head Quarters on the night of the 16th June. The Chateau was being renovated at the time, so we did not have chance to look around inside, but judging from its size it must have accommodated most of Napoleon’s staff as well as his own personal retinue of servants.

From the Chateau we struck out across the French front line towards the right wing of their position, just in front of the villages of Boignée and Balatre. This part of the field was held, on the Prussian side, by elements of General Thielemann’s corps. The two villages mentioned above are a little forward of the Linge stream, which by itself constitutes no great obstacle, but was, even at the time of our visit, surrounded by very marshy meadowlands and these may have presented problems for the attacker. With this being said, one wonders why Napoleon only covered this area with the cavalry corps of Exelmans and Pajol? Maybe, allowing for the sate of the ground, these troops were only placed here to contain the Prussian left wing, and why Theilemann’s corps was not used to better effect on this part of the field seems strange since, besides from a couple of battalions scattered among the French cavalry, only General Hulot’s division of Gérard’s corps were effectively engaged against the Prussians on this sector. Roads were under construction and new buildings being erected during the time of our visit, and it is possible that the best views of the battlefield around this area, as well as much of the actual terrain itself has now gone forever.

After a quick coffee at Tongrinelle, we drove to Sombreffe. Here the wall surrounding the Churchyard has a cannonball concreted into the stonework. Apparently this battlefield memento was found by a local builder who was repairing the wall around the church and decided to incorporate it into the stonework-nice touch! Many of the larger barns and farms in Sombreffe were used as makeshift hospitals during the battle.

After a quick coffee at Tongrinelle, we drove to Sombreffe. Here the wall surrounding the Churchyard has a cannonball concreted into the stonework. Apparently this battlefield memento was found by a local builder who was repairing the wall around the church and decided to incorporate it into the stonework-nice touch! Many of the larger barns and farms in Sombreffe were used as makeshift hospitals during the battle.

Returning from Sombreffe we followed the course of the Linge stream along to Ligny itself. Here we found the 24 pdr(?) French cannon that sits (or sat) under a very dubious covering of concrete and bending metal supports! A plaque gave the date of the battle, and the information that the cannon itself was used in the battle. I very much doubt if this enormous piece of ordnance would have been used by the French, and rather suspect that it was placed there by some well meaning souls who did not know much about field artillery? Ligny village itself was the scene of a very bloody struggle. It changed hands several times during the battle, and the church and large farmhouses became the focus of some gruesome hand-to-hand combats; the farms of En-Haut and En-bas in particular witnessed much severe fighting. It is said that the little Linge stream, which flows through the centre of the village, and is only a meter or two wide, became so choked with bodies that it enabled the forces of both sides to use them as a human bridge.

Returning from Sombreffe we followed the course of the Linge stream along to Ligny itself. Here we found the 24 pdr(?) French cannon that sits (or sat) under a very dubious covering of concrete and bending metal supports! A plaque gave the date of the battle, and the information that the cannon itself was used in the battle. I very much doubt if this enormous piece of ordnance would have been used by the French, and rather suspect that it was placed there by some well meaning souls who did not know much about field artillery? Ligny village itself was the scene of a very bloody struggle. It changed hands several times during the battle, and the church and large farmhouses became the focus of some gruesome hand-to-hand combats; the farms of En-Haut and En-bas in particular witnessed much severe fighting. It is said that the little Linge stream, which flows through the centre of the village, and is only a meter or two wide, became so choked with bodies that it enabled the forces of both sides to use them as a human bridge.

Leaving Ligny we took the road to St Amand, which is situated roughly one and a half kilometres due west. This village, like Ligny, was also hotly contested by the Prussians under Ziethen and the French corps of Vandamme. The ground to the south west of the village was covered in tall crops during the battle, and the approaching French columns were only visible by the tops of their shakos and their standards-crops in those days growing far taller than our modern hybrid varieties. St Amand itself is set forward of the Linge stream, the road crossing the latter to the north at a small appendix to the village known as St Amand la Haye. There is also another hamlet about three-quarters of a kilometre to the north west of St Armand called, Hameau de St Amand. Both sides furiously contested all three places. It was at Hameau de St Amand that the French division of General Girard attacked so vigorously that its losses in killed and wounded, as well as those worn out by the persistent combat, caused it to be left behind, and it consequently took no further part in the campaign

Leaving Ligny we took the road to St Amand, which is situated roughly one and a half kilometres due west. This village, like Ligny, was also hotly contested by the Prussians under Ziethen and the French corps of Vandamme. The ground to the south west of the village was covered in tall crops during the battle, and the approaching French columns were only visible by the tops of their shakos and their standards-crops in those days growing far taller than our modern hybrid varieties. St Amand itself is set forward of the Linge stream, the road crossing the latter to the north at a small appendix to the village known as St Amand la Haye. There is also another hamlet about three-quarters of a kilometre to the north west of St Armand called, Hameau de St Amand. Both sides furiously contested all three places. It was at Hameau de St Amand that the French division of General Girard attacked so vigorously that its losses in killed and wounded, as well as those worn out by the persistent combat, caused it to be left behind, and it consequently took no further part in the campaign

Taking the road from St Amand la Haye one arrives, after about one kilometre, at the village of Wagnelée. This marked the extreme left of the Prussian position, and was covered by elements of cavalry and horse artillery. Behind Wagnelée, and stretching back towards the village of Brye and Sombreffe, the Prussian corps of Pirch I was ranged in several columns, its right thrown back, or refused, facing the village of Marbais. The views around this part of the field are (were?) excellent, and not too much had been done in terms of building construction, thus allowing an unobstructed panorama of the whole front line, both Prussian and French. Walking across to the farm of Bussy, which Blücher made his Head Quarters during the battle, one also obtains a splendid view of the whole battlefield. Anyone standing here will readily understand Wellington’s concern about the Prussian dispositions. The ground is slightly elevated from the little valley of the Linge stream, and devoid of any cover. For the French artillery, one within range, the Prussian masses must have presented an ideal target.

Taking the road from St Amand la Haye one arrives, after about one kilometre, at the village of Wagnelée. This marked the extreme left of the Prussian position, and was covered by elements of cavalry and horse artillery. Behind Wagnelée, and stretching back towards the village of Brye and Sombreffe, the Prussian corps of Pirch I was ranged in several columns, its right thrown back, or refused, facing the village of Marbais. The views around this part of the field are (were?) excellent, and not too much had been done in terms of building construction, thus allowing an unobstructed panorama of the whole front line, both Prussian and French. Walking across to the farm of Bussy, which Blücher made his Head Quarters during the battle, one also obtains a splendid view of the whole battlefield. Anyone standing here will readily understand Wellington’s concern about the Prussian dispositions. The ground is slightly elevated from the little valley of the Linge stream, and devoid of any cover. For the French artillery, one within range, the Prussian masses must have presented an ideal target.

Leaving Bussy we drove back through St Amand and stopping at the Tombe de Ligny. I never asked the history of this, what appears to be a man made mound. If it a tumulus, then the only other I have come across before of a similar construction was at Ramillies. Maybe they are indigenous to this area of Belgium? Whatever it was built for it is certainly worth the climb to the top for the marvellous views of the battlefield. We hung around at the bottom wondering if, or how we could get access to the mound, it being fenced-off in those days. We noticed some grass covered steps leading to the top and stopped a passing workman to find out where we should ask permission to climb to the top. Off he went, and after a few minutes came back with a bunch of keys. After unfastening the gate at the bottom, he warned us of the state of the steps, and then off he went again saying he would come back and lock-up when we had finished our sightseeing! I do indeed urge anyone who wishes to take panoramic shots of the battlefield to seek out and climb this mound.

Leaving Bussy we drove back through St Amand and stopping at the Tombe de Ligny. I never asked the history of this, what appears to be a man made mound. If it a tumulus, then the only other I have come across before of a similar construction was at Ramillies. Maybe they are indigenous to this area of Belgium? Whatever it was built for it is certainly worth the climb to the top for the marvellous views of the battlefield. We hung around at the bottom wondering if, or how we could get access to the mound, it being fenced-off in those days. We noticed some grass covered steps leading to the top and stopped a passing workman to find out where we should ask permission to climb to the top. Off he went, and after a few minutes came back with a bunch of keys. After unfastening the gate at the bottom, he warned us of the state of the steps, and then off he went again saying he would come back and lock-up when we had finished our sightseeing! I do indeed urge anyone who wishes to take panoramic shots of the battlefield to seek out and climb this mound.

I have been back to Ligny four times since 1982, but each time I have never been able to do the whole battlefield as we did then. Taking small parties of tourists who are really only interested in seeing the field of Waterloo, can be depressing to the military historian, and I am always reminding my groups of the words of John Naylor in his work, ‘Waterloo’ (Batsford Books 1960), “The tremendous reversal of fortune at Waterloo has eclipsed Quatre-Bras and Ligny, and the strategy which gave rise to them, just as it has redeemed Wellington’s grossest errors. Yet without the events of the 15th and 16th of June, Ligny and Quatre-Bras, Waterloo is no more than Hamlet without the Prince.”

Postscript

I am very grateful for information received from M. Jean-Marie Aubry concerning where I erroneously placed the “Tombe de Ligny” on this article. The position from which I took the photographs is NOT the location of the Tombe. The site of the actual “Gallo-roman” mound is to the rear of the Man-Made spoil heaps shown on my photographs, which are of modern construction!

There has also arisen the problem of the Mill at Bussy, which Jean-Marie informs me never existed at the site it has been given in the sources. This would seem to be an ongoing debate as Peter Hofschröer has informed me that although the mill is not shown on the Capitaine or Ferrari maps of the late 18th century, the Prussian Generals, Gneisenau and Müffling state that there was a mill at Bussy!

I will keep visitors informed of developments as and when they occur..

Prussian and French Tactical Deployments.

Roadmaps courtesy of Multi Map.com

Order or Battle

See this page.

Bibliography.

| Beck, A.F. and Donaldson. J.W.E. | Waterloo, London, 1907 |

| Creasy, Sir Edward. | The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World, London, 1893 |

| Fuller, General J.F.C. | The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol, II. London, 1963 |

| Lachouque, Commandant Henry. | Waterloo, Arms and Armour Press, London, 1975 |

| Longford, Lady Elizabeth. | Wellington, The Years of the Sword, paperback edition, London, 1971 |

| Naylor, John. | Waterloo, Bastford Books, London, 1960 |

| Siborne, William. | The Waterloo Campaign, Archibald Constable and Co, London, 1895 |

| Sauders, Edith. | The Hundred Days, London, 1964 |

Other suggested reading:

| Colonel Heymés | “Relation”, Documents Inédits sur la Campagne de 1815, duc d’Elchingen (1840) |

| Gourgaurd, General. | Campagne de 1815, London, 1818 |

| Charras, Lt.-Colonel. | Historie de la Campagne de 1815,London, 1857 |

Photographs

References

| ↑1 | Captain J.W.E. Donaldson and Captain A.F.Beck, Waterloo, page 17-18 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Quoted in Sir Edward Creasy’s work, The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World, page 335 |

| ↑3 | John Naylor, Waterloo, page 64 |

| ↑4 | Edith Saunders, The Hundred Days, page 113 |

| ↑5 | Commandant Henry Lachouque informs us that the Emperor occupied the house of M. Puissant. This became ‘the palace.’ The house was (is?) at the lower end of the town of Charleroi, on the right side of the river. See, Lachouque, Henry, Waterloo, page 67 |

| ↑6 | General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol. II, page 500 |

| ↑7 | Ibid, page 500. See also Fullers footnotes concerning sources. |

| ↑8 | Commandant Henry Lachouque, Waterloo, page 70 |

| ↑9 | General J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, page 500 * Girard’s division remained separated form the II nd Corps, coming under the control of General Vandamme. |

| ↑10 | General J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, page 500-501 |

| ↑11 | Ibid, page 501-502 |

| ↑12, ↑17, ↑18 | Ibid, page 502 |

| ↑13 | Quoted in Edith Saunders, The Hundred Days page 123-124 |

| ↑14 | Edith Saunders, The Hundred Days, page 124 |

| ↑15 | Ibid, page 128-129. Saunders source comes from, Documents Inédits, by J.M.Ney, page 26. Ney’s reply is timed 7 a.m. * For an account of Soult’s dispatch on the 17th June, see Appendix ** See the battlefield photographs and information concerning our visit in 1982. |

| ↑16 | See, Sir Herbert Maxwell’s, The Life of Wellington, Vol. II, page 10. Quoted in J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, footnote 3, page 502 |

| ↑19 | See Lady Elizabeth Longford, Wellington, The Years of the Sword, page 499. Here one is informed, albeit unintentionally, how Wellington still lingered over his dinner, replying to toasts. |

| ↑20 | J.F.C.Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, page 503. In fact Wellington still retained some 17,000 troops at Hal, still believing that Napoleon would attempt to turn his flank. These troops took no part in any of the battles fought on the 16th –18th June. |