“C’est le general soldat qui a gagné la bataille de Solferino.”

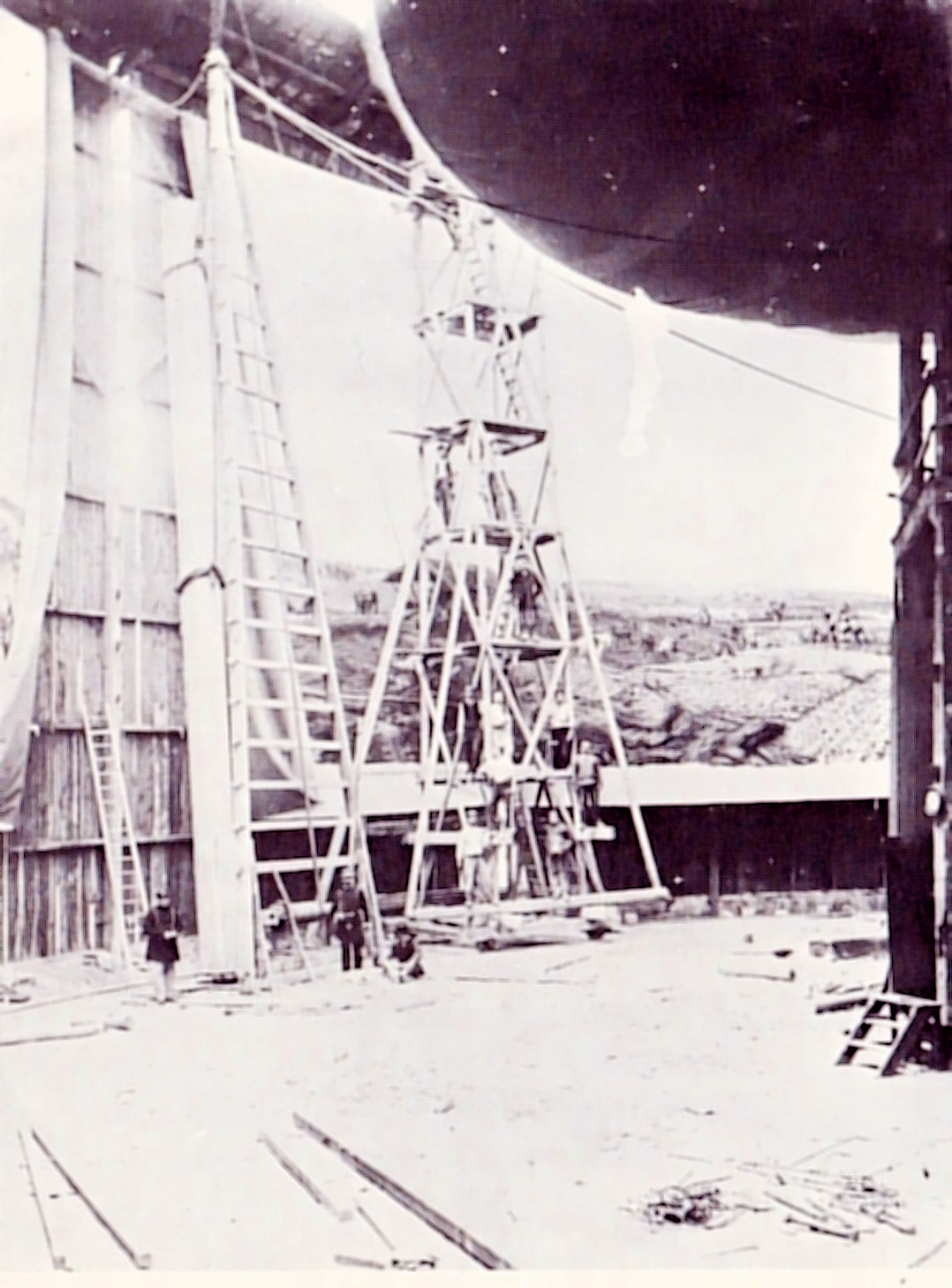

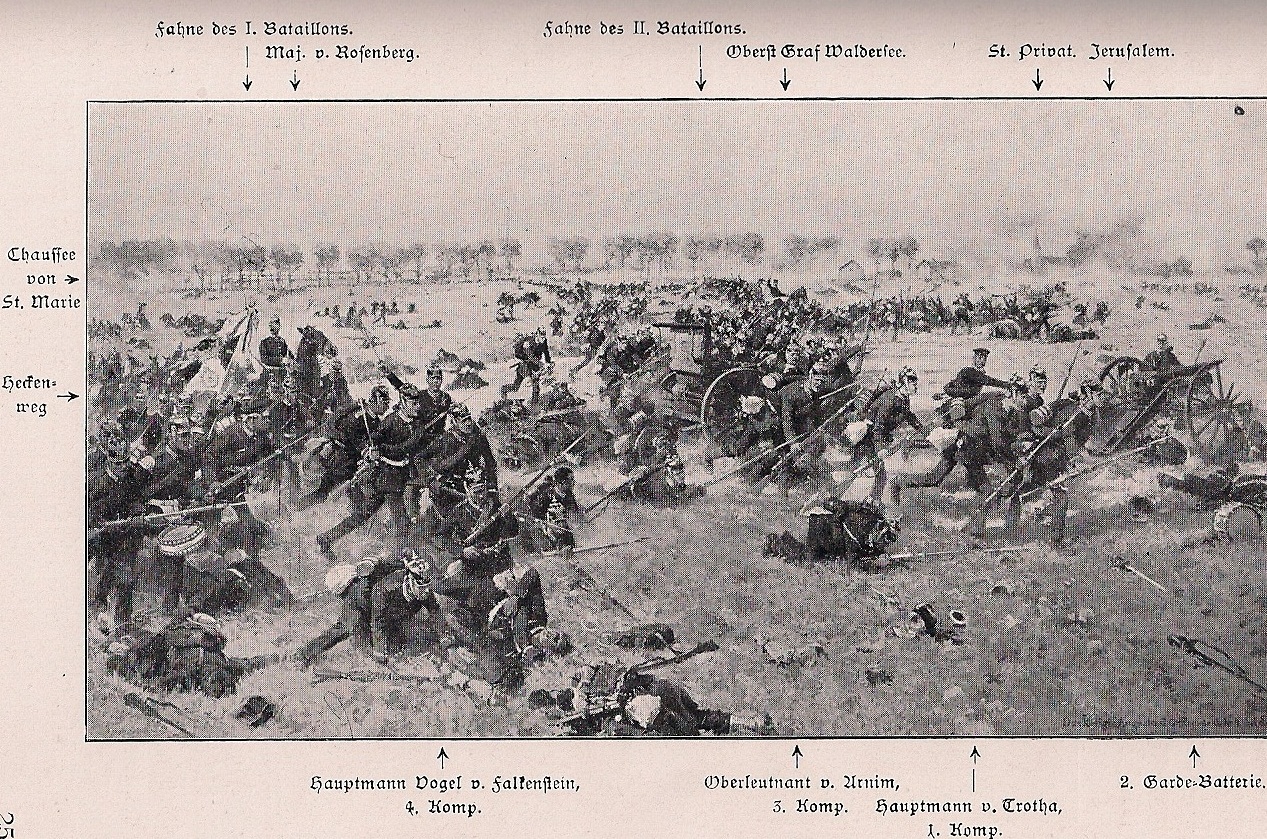

Painting by Aimé Morot.

Introduction

Since I have already dealt with the political build up to the war between France and Prussia/Germany in 1870 in my article, ‘The Battle of Spicheren’, to be found on this site, I will not bore the reader by regurgitating the same information herewith. It is however necessary to spend some time examining the way in which both sides entered the conflict and what steps were (or were not) taken militarily by both belligerents prior to the conflict and during the first crucial encounters that set the tone for the entire campaign.

The French Army.

The Prussian victory over Austria at the battle of Königgrätz (3rd July 1866) had come as a complete shock to Emperor Napoleon III and the French nation as a whole. Now there was no longer any manoeuvring room for Napoleon’s pipe dreams of armed mediation on the Rhine. Indeed, after resting on the laurels of the Crimea War (1853-56) and the Italian War (1859), it was found that, with the exception of the natural fighting spirit that resided in the French soldier, all else was sadly lacking. As Lieutenant – Colonel Baron Stoffel, French Military Attaché in Berlin, had been reporting back with astute accuracy:

August 1868. “During divine service it is upon the King and the army the minister calls down, before all others, the blessing of the Most High. The great bodies of the State are only named afterwards….What a contrast with the position filled by the army in France, where it is but a mass of men, the outcasts of fortune, who lose every day more and more discipline and military spirit.”

August 1869. “The principal points that I seek to make are clear:

“(1) War is inevitable, and at the mercy of an accident.

“(2) Prussia has no intention of attacking France; she does not seek war, and will do all she can to avoid it.

“ (3) But Prussia is far –sighted enough to see that the war she does not wish will assuredly break out, and she is, therefore, doing all she can to avoid being surprised when the fatal accident occurs.

“(4) France, by her carelessness and levity, and above all by her ignorance of state affairs, has not the same foresight as Prussia.

“ … France has laughed at everything; the most venerable things are no longer respected; virtue, family ties, love of country, honour, religion, are all offered as fit subjects of ridicule to a frivolous and sceptical generation…. Are not these things palpable signs of real decay?” [1]Stoffel. Lieut – Colonel, French Military Attaché in Prussia 1866 – 1870. Military Reports (English edit., 1872) pages 93 and 142. Quoted in, Fuller. Major – General J.F.C., The Decisive … Continue reading

Because of rapid mobilization and exceptional staff work, coupled with her adoption of a breech loading rifle, Prussia was able, with some element of luck, to defeat Austria within seven weeks in 1866. France, now realising that she was no longer in a position to demand anything in regard to compensation from her now powerful neighbour across the Rhine, began to take steps to increase the strength of her small professional army. This task fell to Marshal Adolphe Neil who became Minister of War in 1867. Niel’s proposed plan was to raise the numbers of the French army from its present 288,000 to one million. Over the next year and a half various proposals were put forward until a final working plan was accepted by the Corps Législaift which, despite grumblings about expense, gave 800,000 men in the front –line and a trained National Guard of 400,000 in reserve when mobilisation was complete. As McElwee states:

…Honestly implemented, this would have more than met Napoleon’s requirements. By 1875 France would have had a regular army of 800,000 on mobilisation, consisting of men who had served five years with the colours and four on permanent leave. This part of the programme, which would entail no increase of the annual contingent, was running with complete success when war came – five years too soon – in 1870. [2]McElwee. William, The Art of War Waterloo to Mons, page 43.

When Niel died in 1869 his successor, General of Division Edmond Leboeuf (made Marshal of the Empire in 1870), announced to the Corps Législatif that, “So ready are we that if the war lasts two years, not a gaiter button would be found wanting.” This was indeed true, but the problem was that what was lacking was a logistic back – up system that could deliver the army’s requirements on time and at the correct destination. Much of Niel’s reforms were allowed to lapse, with the liberal ministry deciding that, “…disarmament was the most promising form of defence and reduced the army estimates by 13,000,000 francs, conforming to what the cynics called, le Système D, the belief that, ‘on se débrouillera toujours’ –‘ we shall always muddle through.’….” [3]Glover. Michael, Warfare from Waterloo to Mons, page 135.

With apathy among the people towards the Empire setting in it was felt that it would be unwise to change the old method of mobilisation. Regiments were generally posted to garrisons far from their recruiting zones for fear of any political problems occurring in the vicinity of their depot area, thus a double journey had to be made on mobilisation from their garrison back to their depots to take in any reserves and draw war material, and then from the depots to the Concentration Area, all of which caused severe problems on the already overstretched French railway network.

That the French army Intendance lacked organisation, and was at best a hastily improvised affair, is made glaringly obvious by a telegram sent by General Michel, who was the commander of a cavalry brigade (later of the division) attached to First Corps, Army of Alsace (later Army of Châlons) stating, ‘ Have arrived at Belfort. Can’t find my brigade. Can’t find the General of Division. What shall I do? Don’t know where my regiments are.’ And again, on the 27th July, Leboeuf, now Chief – of –Staff to Napoleon, sent a message to General Félix Douay, commander of the 7th Corps inquiring, ‘How far have you progressed with your formations?’ ‘Where are your divisions?’ No one had informed Leboeuf that Douay was still in Paris performing his duties as an Imperial aide–de–camp. When that general arrived at Belfort the next day he replied to Leboeuf in a slightly irritated tone:

For the most part troops have neither tent’s, cooking – pot’s nor flannel belts; no medical or veterinary canteens, medicines, nor forges, or pickets for horses. I am without hospital staff, ouvriers, and train. The magazines of Belfort are empty.[4]Quoted in, Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle: Mars – la – Tour, 16th August 1870, page 53.

Although a work of fiction, The Debacle, by Emil Zola, gives the reader a wonderful impression of the chaos that rained within the French army during the war of 1870. Zola interviewed many veterans of the campaign as well undertaking meticulous research, and since the book was published in 1892, the events he describes had to be carefully explained as there were still politicians and soldiers alive who could question his accuracy.

Despite the chaotic state of mobilisation there were one or two bright glimmers in an otherwise dark and foreboding sky.

Although the shock of Austria’s defeat had rocked Napoleon and his military advisers back on their heels they nevertheless saw clearly that there were lessons to be learnt. The most obvious one was to arm their soldiers with a weapon superior to the Prussian Needle Gun.

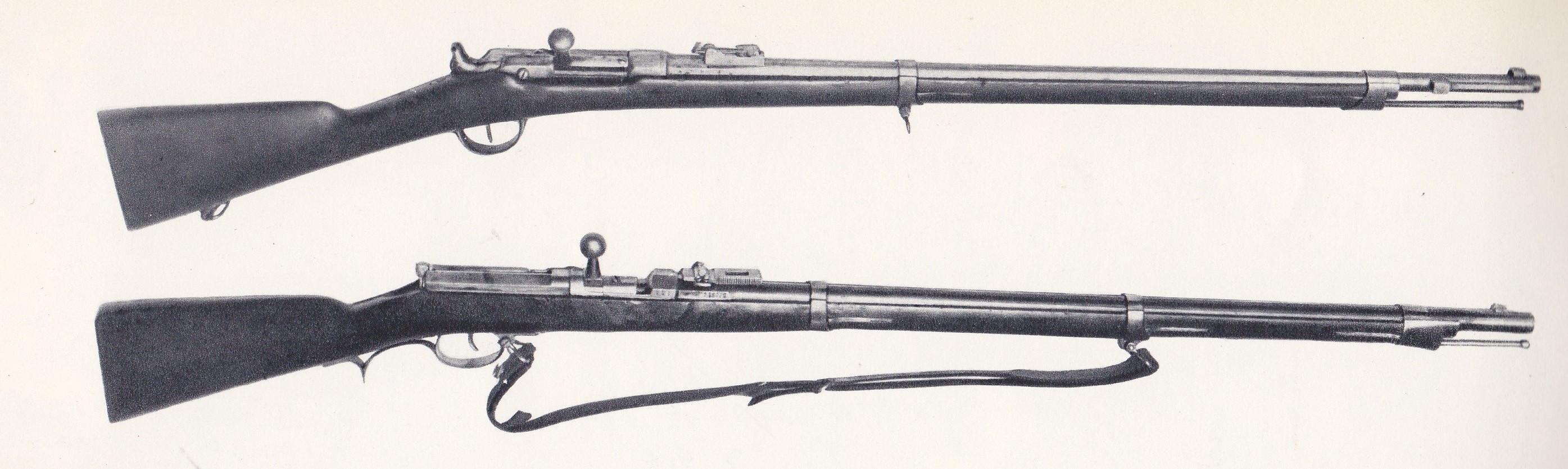

In 1857 Antoine Alphonse Chassepot, working at the artillery factory at St Thomas d’Aquain, began experimental work on a breech loading rifle. The breech was sealed with a rubber ring, solving the problem of escaping gases, which was very prevalent in the Needle Gun, and an improved bolt action mechanism gave a greater rate of fire. Also a reduction in the calibre of the bullet allowed the rifle to be sighted to 1,400 meters, eight hundred meters greater than its Prussian counterpart. The reduction in bullet calibre also lightened the weight of the cartridges and made it possible for the infantryman to carry more, this in spite of the complaints of some general officers that a higher rate of fire would cause ammunition to be used too quickly, thus exhausting their supplies. However, only fifteen months after Königgrätz, the French War Ministry put Chassepot’s rifle into mass production, and by 1870 the army had one million of them, either with the troops or in reserve.[5]McElwee. William, The Art of War Waterloo to Mons, page 140.

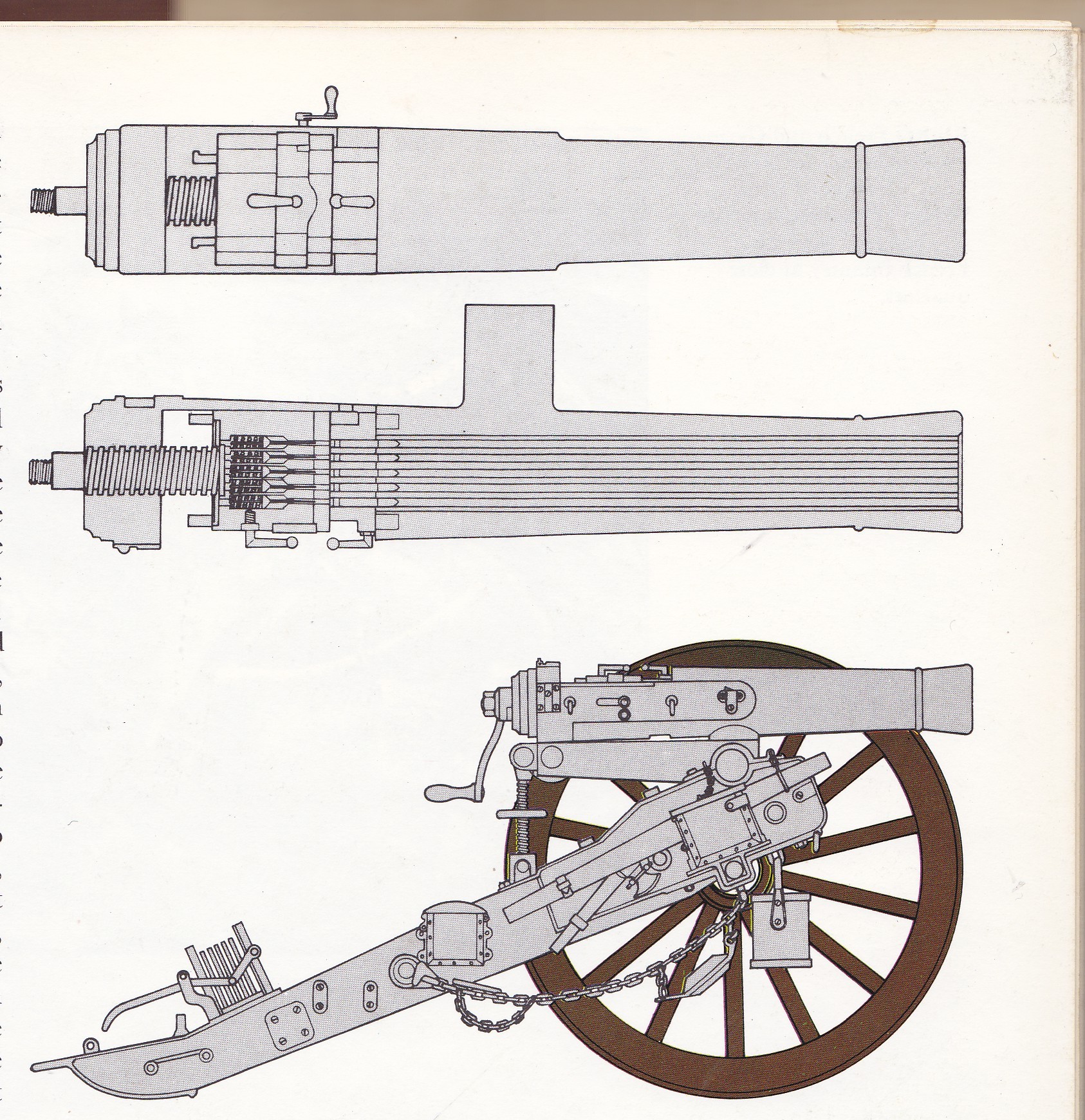

The second innovation to the France’s military arsenal was never used effectively during the war, and thus possibly the most important military technological advancement of its time was never exploited to its full potential.

The mitrialleuse, or volley gun, was first invented by Belgian Captain Fafschamps in 1851, ten years before the Gatling gun, and another Belgium manufacturer, Joseph Montigny developed an improved version in 1863. This hand cranked 37 barrelled mitrialleuse was looked at by the French who then decided that they could build a similar weapon themselves. In 1866 manufacture began, in great secrecy, under the direction of Verchéres de Reffye, of a 13 – mm five tiered 25 barrelled gun, encased in a bronze cover. Its rate of fire was 130 rounds per minute with a range of 1,200 meters. It weighed approximately 800 kilograms and required a six horse team to transport it. The original idea was to use the gun to replace case shot, but if it had been properly handled as an infantry support weapon in the front line its fire, together with the devastating fire of the Chassepot would have negated the effect of the superior Prussian artillery batteries by forcing them far enough back to allow the inferior French muzzle loading cannon to move close enough forward to give their infantry overwhelming support. Instead it was used like a normal artillery piece, kept well behind the lines in grouped batteries. As well as these tactical errors, the development of the gun had been kept so secret that it was not issued to the army until only days before the outbreak of hostilities and consequently few knew how to use it, men having to be trained in its handling while on campaign. One of the only French high ranking offices to appreciate the guns potential was old Marshal Franҫois Certain Canrobert who later bemoaned the fact that it had been used so ineffectively. He was fully convinced that if he had been given a dozen or so to tuck – in along the front line at St Privat, he would have not only totally destroyed the Prussian Guard but would also have been able to thin out his front line so as to have sufficient troops to contain the Saxon flanking attack. [6]McElwee. William, The Art of War Waterloo to Mons, page 146.

The French high command, although their courage under fire can never be questioned, had not had any real experience dealing with the problems involved in a major European conflict. True, generals such as Canrobert, MacMahon, Bourbaki, Bazaine, Leboeuf and Ladmirault had all seen a great deal of action, but much of this was in “small wars” in North Africa, and even the Empires excursion into the Crimea and Italy (and the debacle in Mexico) really bore no comparison with what would be entailed in coming up against a first rate military power such as Prussia had now become. The Emperor himself was in no fit state to lead an army, a fact he would soon realize. His lethargy and illness cast a sad shadow over the army and the French nation as a whole.

The Prussian Army.

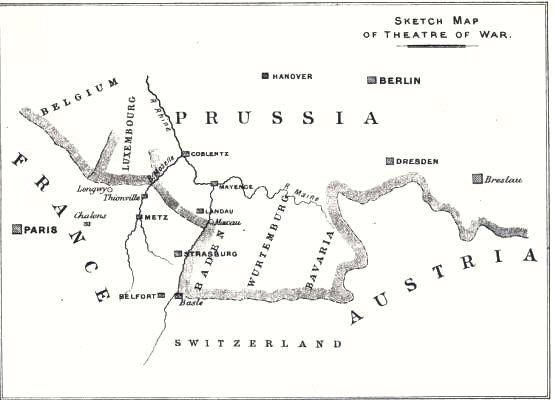

In all probability General Helmuth von Moltke’s most priceless contribution to warfare was his tireless work on the concentration and speed of the mobilisation of Prussian forces as a war – winning factor. The errors that occurred during the campaign of 1866, although not entirely ironed out were, nevertheless, reduced dramatically. The winter of 1868/69 was a time of great activity, with Moltke and the Prussian General Staff working out plans for an offensive war against France. These plans now included the incorporation of the North German Confederation, which boosted the Prussian army to twelve regional corps commands – eight Prussian, one from Schleswig – Holstein, one from Hanover, one combined from Electoral Hesse, Nassau and Frankfurt, and one from Saxony; the Grand Duchy of Hesse supplied one division to the eleventh corps. [7]Bucholz. Arden, Moltke, Schlieffen and Prussian War Planning, page 47. The South German States of Baden, Württemberg and Bavaria, despite any hopes on the part of Napoleon that they would join him once war was declared, threw in their lot with Prussia, increasing its strength even further. Within eighteen days of mobilisation Moltke had over 381,000 men in three armies concentrated in a huge arc along the French frontier.

This mass of men, horses and material were able to concentrate rapidly due to three main factors. First was Germany’s position in central Europe, one that had always been a serious concern militarily, being surrounded on all sides by potential enemies, but now was turned into an asset because her railways, operating on excellent interior lines, would enable her to move large armies from front to front more rapidly than any of her neighbours. The second factor was the meticulous calculations and study that Moltke had given to railways and the formation of a Railway Section as part of the General Staff. The third factor, and possibly the one of most importance, was the Prussian military minds influence on almost all of the nation’s affairs, thus the military option always prevailed over the commercial and civilian. [8]McElwee. William, The Art of War Waterloo to Mons, page 118.

While the French had no peacetime organisations for their army in regard to brigades, divisions and corps, these being only formed upon mobilisation, the Prussians had a system of territorial decentralisation that allowed for their respective Corps Staffs to deal with mobilisation while their General Staff worked on the concentration and the Aufmarsch.

With their aptitude for Teutonic precision the Prussian corps was organised on standard lines, two divisions of two brigades each, with two infantry regiments of three battalions to each brigade. All formations were regionally based and were permanently established in peace and in war. Thus, in the I Corps there would be 1st and 2nd Divisions, and within each of these the brigades would be similarly numbered, and so on throughout the army. Each corps was self contained when on campaign with its own supply train, engineer and medical sections. A cavalry regiment and a Jäger battalion, plus six or more batteries of artillery made up its complement. [9]Ibid, page 65.

Another factor that gave the Prussian army a distinct edge over its opponent was their Great General Staff. When he took over as Chief – of – Staff in 1857, Moltke found a ready – made body of dedicated professionals within Clausewitz’s Kriegsakademie who were constantly working on the problems involved in the event of war. What Moltke did was to groom and personally train a selected dozen of these professional soldiers each year in staff rides and Kriegspiel. These officers would then be allocated to the staffs of higher formations where they would disseminate Moltke’s ideas so that a common doctrine was obtained throughout the army. It did not always run smoothly, but it was far superior to the bungled efforts of the French high command.

The one great mistake Moltke made in 1870 was in clinging to the Dreyse needle gun as the main armament of his infantry. He knew full well in November 1867, only fifteen months after the battle of Königgrätz, the potential of France’s new weapon when French General de Failly, who had just won a victory over Garibaldinian irregulars at Mentana in Italy, sent a rather tactless telegram which contained the statement: ‘Les fusils Chassepot ont fait mervelle.’

The defects of the needle gun had been highlighted in 1866 when it was badly outranged by the Austrian Lorenz rifled musket and was treated with some contempt by many Prussian soldiers who had received bad facial burns caused by hot powder and paper escaping from the poor sealing of the breech. Its main attributes were that it was (had been) faster to load and that it could be fired from the prone position. Moltke paid too much attention to equipping his artillery with the Krupp breech loading cannon, especially after the experience of seeing how close the Austrian batteries had come to wreaking his plans at Königgrätz, rather than bother to up – grade the Prussian rifle. This oversight would be bought home to him and the Prussian army time and again on the killing fields of France. Moltke never admitted he had made a mistake by not equipping the Prussian infantry with a weapon, if not superior, then at least equal to the Chassepot. In his selected writings[10]Moltke on the Art of War, Edited by Daniel J.Hughes, Moltke deals with almost every aspect of conflict and how it was either dealt with at the time of a campaign or how it should be dealt with in the event of future wars; no mention is made of his error in not making sure his troops had entered a conflict with a weapon compatible to their opponents or with infantry tactics that took the enemy fire power into consideration.

French War Plans.

On June 30th 1870, In a statement that would come back to haunt him for many years to come, the French liberal Prime Minister, Emile Ollivier, made the sweeping statement that, ‘…the peace of Europe seems better assured than at any previous period.’ On 19th July 1870 France declared war.

Because of the size of her army in comparison to Prussia/Germany, the French had decided, after scrapping other half thought out plans, that in order to give them a fighting chance, a quick offensive across the Rhine would cause the Prussian concentration to stall. In order to get this spoiling attack moving quickly French regiments would move directly to their appointed war stations with their reserve back – up units reporting to the depots and from their being sent to the front in 100 men units. These calculations were supposed to work so that by the fourteenth day of mobilisation the whole French army would be at full strength. The speculative offensive would take place on the ninth day of mobilisation with 150,000 men at Metz and another 100,000 at Strasbourg uniting and moving rapidly across the Rhine; while a further 50,000 troops were forming at Châlons. Thus, it was thought, this would force the South German Confederation to declare neutrality and Austria to join France, combining to march on Berlin. On the 28th July the Emperor took over supreme command with not a single French army corps in readiness to take the field; the stage was set for disaster.

Prussian Plans.

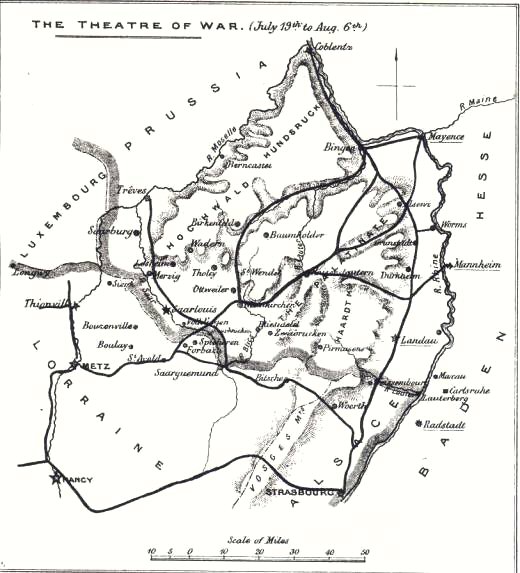

As already mentioned, the Prussian General Staff had already begun preparing plans for war against France back in 1868, and these plans had been upgraded and revised right up until the moment that war was finally declared. The whole essence of the plan was offensive with Paris being the general direction of the advance and the objective to destroy the French army wherever it was met. [11]Fuller. Major – General J.F.C., The Decisive Battles of the Western World. Vol. III, page 107. [11] Working on the assumption that, being superior in numbers and organisation to the French, the offensive would be commenced before their forces could be fully assembled, the concentration would be – viz:

- I Army, General von Steinmetz, VII and VIII Corps; one cavalry division; 60,000 men, to assemble on the River Moselle at Wittlich.

- II Army, Prince Frederick Charles, III, VI and X Corps, the Prussian Guard and two cavalry divisions; 131,000 men, to assemble at Neunkirchen and Homburg.

- III Army, Crown Prince of Prussia Frederick William, V, XI Corps and Bavarian I and II Corps, together with a division each from Baden and Württemberg; 130,000 men, assembled around Karlsruhe in the Palatinate.

- IX Corps, consisting of the 18th Prussian Division and the Hesse Division was united with the XII Royal Saxon Corps to form a reserve of 60,000 men, assembled around Mayence, to reinforce the II Army when required.

Opening Moves.

The sixty –three –year –old General Charles Frossard, former tutor to the prince imperial, was the first to formulate a plan for a French pre-emptive strike across the Rhine, having persuaded his lack – lustre emperor to take the initiative. Napoleon himself was well aware that, given the fact that the Prussian forces gathering on the other side of the frontier were vastly superior in numbers to his own, he nevertheless had to do something; therefore, after receiving information that a detached element (16th Division) of Steinmetz’s I Army was around Saarbrücken holding the Sarr River line, Napoleon ordered the advance. [12]Wawro. Geoffrey, The Franco – Prussian War: The German Conquest of France in 1870 – 1871, page 86.

As Moltke states in his Correspondence 1870 – 71:

The time had gone when they [the French] might have taken advantage of their over – hasty mobilization; the condition of the men had prohibited any action. France was waiting for news of a victory; something had to be done to appease public impatience, so, in order to do something, the enemy resolved (as is usual under such circumstances) on a hostile reconnaissance, and it may be added, with the usual results. [13]Moltke. Graf Helmuth von, The Franco- German War of 1870 – 71, Translation , New York 1892, page 10.

On the 2nd August three French divisions crossed the frontier and then engaged and drove back three Prussian infantry battalions who had been occupying the town of Saarbrücken. Thereafter the town itself was abandoned by the French who took up a position on the high ground to the south – west. Once more, after French headquarters had spent a couple of heady days debating further offensive operations, reality kicked – in and it was realised that, even allowing for its initial success, the French army was lacking in all the necessities to keep the offensive going. The rail system was becoming choked, with supplies piling up at stations while reservists were still being moved forward utilising rolling stock. Thus, after bringing the ad – hoc troop formations together in something like a reasonable offensive force, the Emperor, fearing an imminent invasion, divided his forces with Marshal Canrobert on the right and Marshal MacMahon on the left attempting to cover every possible approach by the Prussian Juggernaut. [14]Glover. Michael, Warfare from Waterloo to Mons, page 136 – 137.

This fragile screen was tested when, early on the morning of 4th August, the Prussian Third Army crossed into France on a wide front moving on Lauterburg and Weissenbourg. The French had only a single division and a cavalry brigade under General Abel Douay along the River Lauter at Wiessenburg to confront this advance. By 10:00 a.m., after a stubborn resistance, Douay ordered a retreat, being killed by a shell as he was checking the fire effect of a mitrailleuse battery. Ironically, although the French were falling back they were still causing many casualties on the Bavarian troops attacking, having occupied many of the rooftops and bedrooms in the town from which a constant sniping fire was maintained, it was the townsfolk of Wiessenbourg who eventually ended the battle when, not wishing to see their town damaged or destroyed, they ran up a white flag and opened the gates for the Bavarian troops to enter: ‘Here was an early instance of defeatism that would plague the French war effort from first to last.’ [15]Wawro. Geoffrey, The Franco – Prussian War: The German Conquest of France in 1870 – 1871, page 101 -102.

This fragile screen was tested when, early on the morning of 4th August, the Prussian Third Army crossed into France on a wide front moving on Lauterburg and Weissenbourg. The French had only a single division and a cavalry brigade under General Abel Douay along the River Lauter at Wiessenburg to confront this advance. By 10:00 a.m., after a stubborn resistance, Douay ordered a retreat, being killed by a shell as he was checking the fire effect of a mitrailleuse battery. Ironically, although the French were falling back they were still causing many casualties on the Bavarian troops attacking, having occupied many of the rooftops and bedrooms in the town from which a constant sniping fire was maintained, it was the townsfolk of Wiessenbourg who eventually ended the battle when, not wishing to see their town damaged or destroyed, they ran up a white flag and opened the gates for the Bavarian troops to enter: ‘Here was an early instance of defeatism that would plague the French war effort from first to last.’ [15]Wawro. Geoffrey, The Franco – Prussian War: The German Conquest of France in 1870 – 1871, page 101 -102.

Crown Prince Frederick William now halted the forward movement of the III Army while his cavalry arrived and thereafter continued the advance. By the evening of the 5th August his troops were disposed as follows: right wing, II Bavarian Corps around Langensulzbach, with units pushed towards the main highway from Bitche and Haguenau; centre, V Corps facing Wörth; left wing, closing on Gunsett, XI Corps. The Bavarian I Corps was held in reserve behind the centre, while the Baden and Württemberg divisions were combined under General von Werder as a reserve behind the left wing. [16]Ascoli. Davcid, A Day of Battle: Mars – La – Tour 16 August 1870, page 79.

After viewing the engagement at Wissembourg and its consequences from the heights of the Col de Pigeonnier, Marshal MacMahon realised that with the rout of Douay’s division his own position could be compromised, however,

‘…He could do nothing to help his luckless subordinate; indeed he could see, from the size of the black columns which were creeping by every road and track “like an oil stain” over the frontier, that his own position was in serious danger. But he remained impassive. By borrowing a division from the 7th Corps he reckoned that he could still stand in the strong Froeschwiller position, as he had always intended, and if another corps were put at his disposal, he wired Metz that night, he hoped to be able to even take the offensive. The Emperor replied by putting Failly’s 5th Corps under his command; and on the 5th August, while the divisions of the 1st Corps [MacMahon’s own] concentrated round Froeschwiller and Félix Douay [Abel Douay’s brother] packed off Conseil Dumesnil’s division from 7th Corps by train from Belfort, MacMahon summoned Failly to bring his corps south through the Vosges’. [17]Howard. Michael, The Franco – Prussian War, page 105.

Fröschwiller – Wörth.

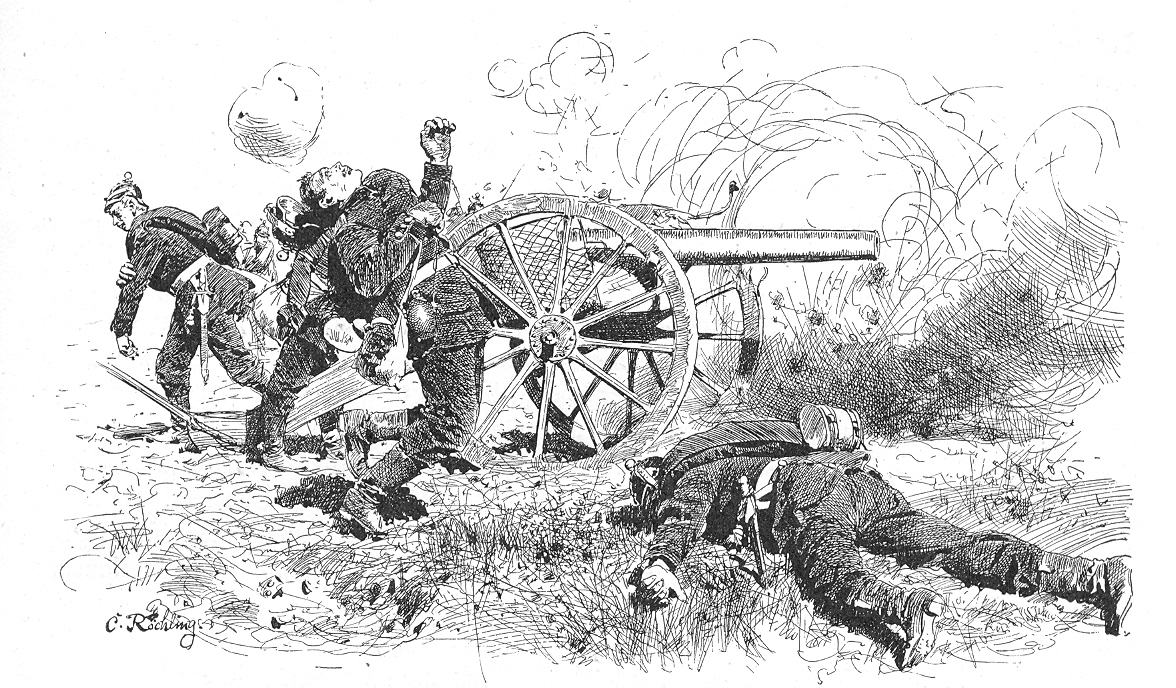

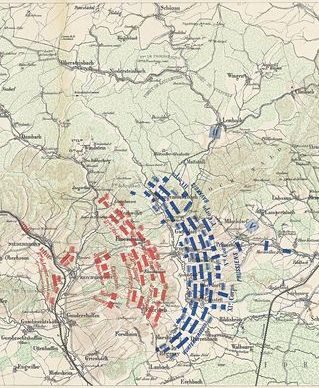

On 6th August the battle of Fröschwiller – Wörth was fought when the commander of the advanced units of the German V Corps, considering that the activity along the high ground occupied by the French was a sign of their pulling out and retiring, decided to push on and test the enemy position, bringing on an engagement that neither Moltke nor the Crown Prince had anticipated or desired. Wading across the Sauer, the bridges in their area having been destroyed by the French, the skirmish line of the Prussian 20th Brigade (V Corps) were greeted by heavy chassepot and mitrarilleuse fire forcing them to retire back over the stream to the protection of their artillery line, by which time the sound of gunfire had caused the Bavarian II Corps commander, General Hartmann, to march to the sound of the guns. Without much tactical finesse Hartmann ordered a rash and uncoordinated attack on the strong French left wing which was driven back without much trouble by General Auguste Durcrot’s well entrenched infantry holding the tree covered slopes to the south, and thereafter the fighting died down on this flank.

Over on the French right flank at around 8.30 a.m., General Lartigue’s artillery began to fire on the advancing units of the Prussian XI Corps who were now also arriving to support their comrades in V Corps, the superior calibre of their breech loading Krupp guns soon forcing the French batteries to pull back. Seeing that both wings of MacMahon’s line were managing to hold, the commander of the Prussian V Corps, the impetuous General von Kirchbach, although he had been ordered not to enter into a full blown engagement, now threw restraint to the wind and instructed his own corps and the Bavarian’s to press the attack. [18]Ibid, page 111.

The battle developed all along the line and became one in which the superiority of the French rifle was pitted against the accuracy and range of the German artillery, and although MacMahon’s units continued to hold on grimly, the mounting pressure on Lartigue’s position began to cause him alarm:

‘…a black swam of Prussians emerged at the run from the Gunstett bridge with every appearance of disorder. From this ant – heap, as if by magic, company columns shook themselves out and rapidly and without hesitation took up perfect regular formation’[19] Bonnal, Froeschwiller, page 315. Quoted in, Howard. Michael, The Franco – Prussian War, page 111.

By 1.00 p.m., the Germans had driven a wedge between Lartigue’s division and the division of General Conseil Dumesnil’s on his right, capturing the village of Morsbronn and Niederwald, threatening the whole French positions lateral line of communication and effectively turning their flank[20] Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle: Mars – la – Tour 16th August 1870, page 81.. With his last infantry reserve put in Lartigue fully realised that unless he could gain time to re-establish a line from east to west along the Niederwald ridge he was in danger of being totally surrounded, and therefore called upon the only fresh force available to cover his fall back, the cavalry.

Even allowing for the rigours of a campaign griming their uniforms and dulling their normal parade ground splendour, the advance of a body of cavalry was still a stirring and magnificent sight. With a creaking of leather and the jangle of harness, 1,000 mounted cuirassiers and lancers swung into line and began to advance on Morsbronn. Unfortunately their rout took them over, ‘un terrain détestable’, the ground being covered in vines and ditches which caused the squadrons to lose their alignment. Still moving forward in a confused mass they were greeted at 300 meters range by such a storm of lead that, ‘un quart de la brigade tomba en route. Le reste s’engouffra dans les rues barricade du village où l’infanterie prussienne installée dans les masion le decimal en tyrant des fenêtres.’ Piles of men and horses covered the ground, the remainder managed to extricate themselves and get back to their own lines. [21]Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle: Mars – La – Tour 16 August 1870, page 81.

With pressure becoming greater by the moment, at 3:00 p.m. the French had been forced back into a two kilometre quadrilateral which was being pounded continually by enemy artillery. Finding himself in a similar position to the one encountered by Lartigue, MacMahon also called upon the cavalry to check the enemy advance and allow time for a retreat. [22]Howard. Michael, The Franco – Prussian War, page 115.

Once again, as if to drive home the fact that cavalry was no longer a force to be reckoned with on the battlefield when pitted against rapid rife fire, the 2,000 cuirassiers of General Bonnemain’s division were decimated as they attempted to get to grips with their foe. Reforming and charging again and again it is probable that not one trooper ever made contact with the enemy, the ground being obstructed by hop – fields and vine – yards, from the cover of which the Prussians, scattered in small groups, kept up a continued and devastating fire; Bonnemain’s gallant squadrons finally retired, leaving over a third of their number on the ground, ‘C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas la guerre.’ [23]Ascoti. David, A Day of Battle: Mars – La – Tour 16 August 1870, page 82.

Although proving the point that as a missile weapon cavalry were now as obsolete on the modern battlefield as elephants became to ancient armies, Bonnemain’s sacrifice did allow time for MacMahone to disengage the rest of his forces and begin a retreat. By 5:00 p.m. on his right wing the divisions of Pellé and Dumesnil, which had been cut off from the rest of the army when the Prussians drove a wedge into the French position, escaped south towards Haguenau. The left wing and central formations fell back towards Niederbronn and Reichshoffen were their retreat was covered by the 5th Corps. The French casualties had been significant with almost 6,000 officers and men killed or wounded and a further 9,200 taken prisoner, including 28 guns.

The Prussians made no attempt to carry out a pursuit, their cavalry being too far in the rear, and in any case the losses incurred were such that the Crown Prince considered his army to be in no fit condition to seek another engagement having sustained a total of 10,600 officers and men killed and wounded.

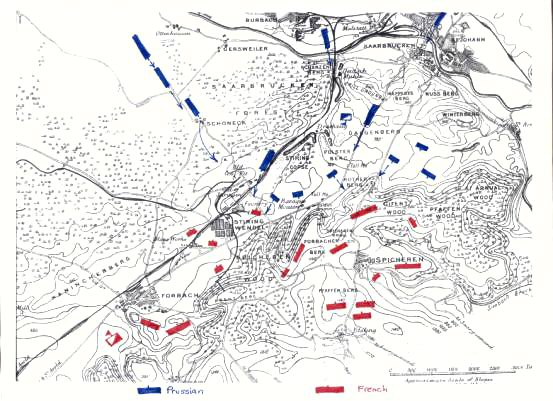

Spicheren.

The fateful day of 6th August 1870 was a dark one in the annals of French military history, for while MacMahone was being pounded at Froeschwiller, the Prussian I Army under Steinmetz was engaged in a battle that, because of his reckless and insubordinate attitude, he should not have won and the French, if they had not squandered every opportunity that presented itself for victory, should not have lost.

Even with the best of planning warfare always throws up imponderable problems, especially at human level. Moltke’s concept concerning the dissemination of his ideas and orders for a common doctrine to be maintained throughout the army, but still allowing for the individuality of separate commanders, fell far short of what he intended as had been shown at Froeschwiller, and was to be tested again in more serious fashion.

General Charles von Steinmetz, commander of the Prussian I Army, would prove to be one of the most cantankerous and disobedient subordinate that Moltke had to cope with until his removal, albeit after he had squandered the lives of thousands of soldiers, in 1871. Born in1796 Steinmetz had seen action during the Napoleonic Wars and gradually rose through the ranks becoming a Major – General in 1854. He served with distinction during the Danish War of 1864 and commanded a corps during the Austro – Prussian War of 1866 where he was given the sobriquet “The Lion of Nachod” for his part in that battle. He made few friends owing not only to his poverty stricken background, but also due to his rather arrogant attitude and Spartan lifestyle. His willingness to sacrifice the lives of his soldiers to achieve his objectives coupled with gross insubordination could quite easily have ruined Moltke’s careful planning on more than one occasion.

Steinmetz’s first act of overzealousness and disobedience occurred when, on the 6th August Moltke, being disappointed that the French offensive had apparently now stalled as he would have liked them to have pushed on into the Saarland where they would have been totally surrounded, decided altered his plans and to trap them where they were. To this end he ordered I and II Armies to contain the enemy in front while the III Army under the Crown Prince came in around on their right taking them in rear. [24]Glover. Michael, Warfare from Waterloo to Mons, page 137.

During the early hours of 6th August Moltke was informed by Steinmetz that he was going over to the offensive, proposing to strike at St Avold and Saarbrücken. With his usual arrogance he failed to inform Frederick Charles of his intensions which, in turn, threw the whole of Moltke’s carefully worked out tables of march into confusion with two German armies advancing on the same objective.

When the French corps of General Frossard had taken possession of Saarbrücken during the heady advance of 2nd August the position he had taken up in the hills overlooking the town and parade – ground had been, what Frossard himself later wrote, ‘ma position était aventurée.’ Now he gave this ( what would prove to have been ideal) ground up and retired his II Corps one mile south – west to the heights near Spicheren, a ‘position magnifiques’ that he had personally, being trained as an engineer, reconnoitred before the war. That Frossard was not supported in his stand at Spicheren by the other elements of the Army of Metz, who were positioned in haphazard formations, more prepared for retreat than aggression, was another example of the complete ineptitude that plagued the French high command.

Frossard’s position was indeed formidable with steep sided hills and woods covering the approaches from the River Saar and the massive ironstone cliff, the Rotherberg (Red Hill), dominating the centre. On the right the slopes down to the river were covered by the forest of the Gifertwald, the terrain accessible only to infantry. On the left the ground fell steeply into the constricted valley where the road from Saarbrücken to Forbach ran, continuing from there to St Avold. Any attack from Saarbrücken would have to use this route and would then be confronted by the massive structures that constituted the great Stiring – Wendel ironworks, which stood like a fortress in the valley. The only flaw in this defensive line was that the whole position could be outflanked if the attacker masked the crossing at Saarbrücken and crossed the river at Völklingen, thereafter turning south down the Rossel valley and striking at Forbach from the rear. Frossard fully realised that holding the high ground alone was not going to be sufficient and in making arrangements for his 22,800 men he took this very much into consideration. First he placed Vergé’s division in the valley and garrisoning the village of Stiring – Wendel and the ironworks; Laveaucoupet’s division held the centre and right wing, with two companies dug – in on the Rotherberg; Bataille’s division was kept back in reserve near Oetingen, from where it could be used to blunt any attack coming against Forbach from the direction of Völklingen. The cavalry were placed well behind the infantry line but no outposts had been pushed forward to watch the river crossings. The spade now complemented the rifle, unfortunately allowing defence to become the dominant factor to the detriment of bold action. [25]Howard. Michael, The Franco – Prussian War, page 90.

In true gung – oh style, more fitted to a twenty year old than to a septuagenarian, Steinmetz pressed on with his own attack plans, veering across the march route of Prince Friedrich Charles’s II Army and causing consternation in that armies forward units. When the VII Corps of Steinmetz’s I Army came within sight of the French position at Spicheren the commander of its 14th Division, yet another “I do it my way” field officer, General von Kameke, asked for permission to attack. His superior, General Zastrow, readily stated that Kameke could do as he saw fit thus, in so doing, displaying a total lack of any understanding of Moltke’s intentions and bringing on an engagement that should, with a more aggressive attitude on the part of the French, have thrown the whole of Moltke’s carefully planned arrangements dangerously out of gear.

By noon Kameke division was attacking in open order across the open fields in front of the Rotherberg, eventually managing to gain the foot of the cliff and thereafter assaulting the summit where a few companies of the 40th and 74th Regiments drove off the French defenders and established a precarious toehold, a hold which Frossard made no attempt to challenge, seemingly being content to just contain the enemy rather than drive them off[26]Elliot – Wright. Phillip, Gravelotte – St – Privat 1870, page 42.. This strange state of affairs was to be repeated time and again during the course of the battles of Mars –la – Tour and Gravelotte/ St – Privat, showing a distinct shift in the French high commands thinking in regard to tactics. Even Napoleon I had embraced the protective principle which he defined as, ‘The whole art of war consists in a well reasoned and circumspect defensive, followed by rapid and audacious attack.’ [27]Corresp. XIII, No. 10558.. Now the defence seems to have taken precedence.

Frossard was not alone in failing to exploit the haphazardous decisions and pig headed attitude of Steinmetz and his subordinates. In rear of Fossards corps, at no more than eighteen kilometres distance stood over 40,000 troops, these forces could, if they had been brought together with Frossard’s formations, not only have given Steinmetz a severe hammering, but would also have knocked most of the stuffing out of Moltke’s original well conceived plans. But as Howard say’s:

‘It was certainly not because the German attack achieved strategic surprise. Earlier that morning, before the Uhlan patrols appeared, Lebœuf had wired to both Bazaine and Frossard, warning them to expect an engagement. Frossard querulously endosed the message, “Then why not order Marshal Bazaine to concentrate his positions on mine and take over command of both?” But Bazaine, at St Arvold, was not only Frossard’s superior officer; he had also his own responsibilities as a corps commander, and he knew that Saarbrücken was not the only point at which the enemy might attack. Uhlan patrols had also been active on either side of the town, raiding the communications between Sarreguemines and Bitch and penetrating deeply into the St Arnual Forest. The main enemy attack might by – pass Frossard and come in on the left or right flank of the 3rd Corps itself. It is not surprising that Bazeine should have been cautious about committing his entire forces to Frossard’s support until he was sure that the attack from Saarbrücken was serious; and not until nearly 6:00 p.m. did any message from Frossard suggest that it was[28]Howard. Michael, The Franco – Prussian War, page 92.. Castagny is not mentioned in many OOB’s of the campaign, his division being given as Nayral. ))

This may indeed be true but General Castagny, * showing a rare glimpse of former French independence of mind, hearing the rumble of battle, began to march in its direction, albeit briefly, but then halted after being informed by some peasant’s that the fighting had ended[29]Ibid, page 92. . Nevertheless, even allowing for Bazaine’s worries concerning the possible alternative approach of the Germans, he should not have hesitated in dispatching at least part of his force to back – up Frossard; and it does beg the question that if Castagny had been able to hear the sounds of an engagement, why not Bazaine? Finally, Moltke himself wrote, not as yet knowing that Stienmetz had bought on a battle that:

‘…As to intentions of enemy main body, as yet only conjecture.

His most correct measure would perhaps be a general offensive against Second Army, which, as the head of its columns are constantly advancing, has not yet been able to close up with all its corps. Yet the French would strike with superior forces and a vigorous resolve is little in accord with their conduct hitherto….’[30]Moltke, Military Correspondence 1870 -71. No 113..

It would appear that even Moltke seems to have expected the usual French Furia Francese?

Regardless of these counterfactual arguments, by 3:00 p.m. on the afternoon of the 6th August the German units, in distinct contrast to their French counterparts, were approaching the battlefield in ever increasing numbers and guns. Command of these converging units now passed into the hands of the highest ranking officer now present on the battlefield, General Constantin von Alvensleben, who’s own III Corps of the II Army were approaching from the north – east. With the French chassepot proving its worth in holding back the German infantry attacks, Alvensleben plastered Frossard’s positions with a deluge of artillery fire. Despite this pounding it was touch – and – go for the Germans all through the afternoon, and at close to 6:00 p.m. their right wing, about which Alvensleben had no knowledge, was teetering on the verge of collapse, while in the centre and on the left the troops were worn out and pinned down by heavy rifle fire. A counter – attack in strength by the French could have sent the whole lot tumbling back in the utmost disorder, pining them against the river. It never came[31]Howard. Michael, The Franco – Prussian War, page 97. .

The gallant but purely defensive stance of Frossard’s corps enabled Alvensleben to put in fresh assaults which eventually began to tell, and by 7:00 p.m., with no sign of support arriving despite having sent urgent messages to Bazaine, and with his left flank in danger of being turned, Frossard was forced to retire, darkness covering his retreat. [32]See “Dossier Frossard” Paris, 29 November 1870, General Castagny, “Reponse à la brochure du General Frossard en ce qui concerne la Division de Castagny pendant la journée de Frossard.” … Continue reading

German losses amounted close to 5,000 killed and wounded; French casualties were lower at around 2,000, but a further 2,000 unwounded prisoners also fell into German hands. As the hungry and tired French troops trudged away from the battlefield a sense of despondency set in, with no shortage of derision being bought down on the heads of their leaders whose irresolution and ineptitude was considered as being the reason for their defeat.

The Fortress of Metz.

Although the twin defeats of the French at Fröschwiller – Worth and Spicheren had not been decisive enough in themselves to cause a military collapse, they would change the attitudes of both Napoleon and the French people. For the Napoleonic dynasty, which pinned all its hopes of survival on a military victory, its existence now became a crucial factor for the Empress Eugénie and her Regency Council, with the opposition, forgetting their role in supporting the war, now looking for reasons to bring down the whole Imperial edifice. As for the population, and in particular the perfidious nature of the Paris mob, the cry of ‘Ȧ Berlin,’ had now been replaced by murmurings of dissolution and discontent. At the meeting of the Government Assembly on the 9th August the elected representatives of France heard Jules Favre and Leon Gambetta, the two leading members of the opposition, declare that what the regime was accused of was not in making war but in making it, ‘ complacently and with culpable incompetence.’ Clearly Napoleon was held to be responsible for both the political and military crisis that was now looming. [33]Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle: Mars – La – Tour 16 August 1870, page 92.

The result was that Ollivier and his cabinet were driven from office and General Count de Palikao took on the mantel of chief executive as well as that of Minister of War, once more showing that the left hand of the country did not know what the right hand was doing, General Leboeuf also still held the title of Minister of War[34]Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle: Mars – La – Tour 16 August 1870, page 93. .

At French Imperial Headquarters in Metz on the 6th August, just as the guns began to thunder at Fröeschwiller and Spicheren, Napoleon and his staff were in the process of concocting yet another offensive plan. It was now decided that the army should be concentrated at Bitche, at which point its whole weight could be used to best effect. Even after receiving telegram messages from Bazaine at St Arvold, clearly stating that the enemy had been engaged, Napoleon still maintained that he would now be taking the offensive. With the army taking position at St Avold it would be able to strike the advancing Germans on terms of localised superiority. The plan was so feasible that even von Moltke himself considered it the most obvious and best thing the French could do but adding, “…such a vigorous decision is hardly in keeping with the attitude they have shown up till now.” Sure enough this well conceived plan was soon relegated to the rubbish bin when, on the morning of the 7th August, news began to arrive that the Germans had taken Forbach; that no news was forthcoming from Frossard, and that St Avold was now threatened. All this caused Napoleon to abandon any thoughts of an offensive and order an immediate withdrawal of the army to Châlons. As for the Emperor himself he: ‘…returned to his headquarters in a state of moral and physical collapse.”[35]D.T. I 61. Revue de Paris 154 (Sept – Oct. 1929) 505 – 7. Napoleon III, Œuvres Postumes, ed. Le Comte de la Chapelle. (Paris 1873) 43. Quoted in, Howard. Michael, The Franco – Prussian War, … Continue reading

Over at German headquarters Moltke had his own problems to deal with. Steinmetz’s overzealousness and downright disobedience had caused total confusion among the units of the left wing of his I Army and the right wing of the II Army, a confusion that was not helped when, after issuing fresh instructions to First Army to clear the way for the Second Army to move south – west on the Saar from Neunkirchen and Zweibrücken, Steinmetz once more chose to ignore his new instructions. These new orders were, after securing the railway communications at Forbach, to advance on the road from Saarlouis to Metz as per his original instructions, keeping in close touch with the left wing of the French army. As David Ascoli puts it:

Steinmetz would have none of it. He was sulking; he did not accept Moltke’s authority; and when it was made clear to him that the role of I Army was to protect the right flank of the great advance, he, as it were, broke off diplomatic relations with Royal headquarters, and – to make his point – insolently withdrew his hunting – pack of two cavalry divisions, deploying one to no purpose watching the Luxembourg frontier, and the other to even less, cluttering up the roads behind his infantry. So it was that Ladmirault’s 4 Corps on the French left slipped away under dark drenching skies towards the protective guns of Metz.[36]Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle: Mars – La – Tour 16 August 1870, page 94.

The French army became dispersed after it defeats in the two battles of the 6th August. MacMahon pulled back to Saarburg with five divisions (one of 7th Corps and four of his own 1st Corps). Another division had fallen back on Belfort where it was joined by the 3rd Division of the Corps formed at Lyons. General Failly’s 5th Corps had retired under the protection of the guns of Lutzelstein, later rejoining MacMahon at Saarburg. During the 7th August two divisions of 3rd Corps linked – up with Frossard’s crestfallen troops at Purtlingen, while two other divisions of 3rd Corps milled around St Avold. The Imperial Guard was to the rear of these units at Luben, with the 4th Corps spread around Helsdorf, Bolchen and Busendorf. It therefore now became imperative to gather these scattered elements together and this was why Châlons had seemed the best place to reorganise. Orders were issued on the 7th to all corps and groupings that could be contacted as follows: 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Corps together with the Guard, to concentrate at Metz and then take route to Châlons; MacMahon and Failly going via Nancy; General Douay’s 7th Corps taking train to the same destination. However because of false information stating that the road to Nancy was already cut by enemy forces, MacMahon chose to turn south. These formations, plus those of Douay’s travelling by train, reached Châlons between 17th and 21st August, utterly exhausted and demoralised[37]Schlieffen. Alfred Count (Graf) von, Cannae, page 191 – 192. .

Napoleon had now decided that Metz was more suitable for the initial concentration of the army, cabling his wife, “…a withdrawal to Châlons has become too dangerous; I will be more useful here in Metz with 100,000 troops.” This statement was, of course, just what the Empress Eugénie wanted to hear, replying that Napoleons imperial duties lay in remaining with the army and not returning to Paris where his presents would be politically unacceptable and would be looked upon as a disgrace. Indeed it does seem as if the empress was quite willing to sacrifice her husband in an attempt to save the dynasty, thereby securing the throne and succession for the Prince Imperial[38]Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle: Mars – La – Tour 16 August 1870, page 96. .

By 13th August almost 180,000 troops were gathered on the right bank of the Moselle close to the fortress of Metz. The food and fodder situation had improved greatly and ammunition was adequate, however the problem of distributing these items to formations that were constantly being reshuffled as plans changed remained a constant concern. These reworking of plans and the general uncertainty in regard to strategy were caused, in the first instance, by Napoleon remaining in command, this causing further problems when the military advisers surrounding him tendered advice in military terms that came into conflict with the political (dynastic) considerations bombarding the Emperor from Paris. In no fit state to balance one factor against the other Napoleon now chose to compromise. He would remain at Metz but hand over command of the Army of the Rhine to one of his senior officers; however this in turn was not without its own problems.

There were four candidates for the post of army commander, MacMahon, Bazaine, Leboeuf and Canrobert. MacMahon was too far distant to be considered and Leboeuf had ruled himself out of the running by his remarks concerning the readiness of the army for war. Canrobert, realising his limitations, did as he had done when offered the command of the French forces in the Crimea fifteen years previously and respectfully declined. But even if he had taken on the job it is doubtful if the radicals would have tolerated him in such a position after his role in helping Napoleon in the coup d’etat of 1851. The Emperors eyes now turned to Marshal Bazaine[39] Elliot – Wright. Philipp, Gravelotte – St – Privat 1870: End of the Second Empire, page 47. .

Marshal Franҫois Achille Bazaine had risen to his position from the ranks and was regarded as one of France’s finest officers. He had served with distinction in the Crimea and Italy, and even the disastrous Mexican affair did not affect his standing as a first rate leader of men. The problem was that Bazaine had never held such a high post as the one now thrust upon him – Commander – in – Chief, and although he would prove to be totally inadequate for the job one must also not forget that the blame for all the woes of France considered due to his mishandling of events should also be shared by those who put him in command in the first place.

The Advance of the German Armies.

When Moltke received the news that the French had fallen back under the guns of Metz, on the 12th August, he immediately took steps to take the offensive which would now entail an advance on a wide front incorporating all three of his armies. The plan was to spread out his forces covering some eighty kilometres and taking in all crossings points on the Moselle River within their scope. On the right wing Steinmetz, still in sulking mode but now under strict control would moved I Army on the axis Sarrlouis – Metz, his forward units on either side of Boulay. In the centre Prince Frederick Charles II Army advanced toward the Moselle River crossings above Metz, while on the left Crown Prince Frederick William’s III Army, now out of contact with MacMahon, was probing forward towards Lunéville and Nancy. It is worth quoting Ascoli here in regard to some criticism levelled at Moltke concerning his apparent dilatory arrangements of the advance:

Moltke has been accused of making haste too slowly, but his critics ignore the iron will which kept one single purpose in view. Clausewitz had also taught him that the essence of war is battle; but Clausewitz had also preached the gospel of concentration of force. He had only to remember that failure to practise what Clausewitz preached had almost lost him the battle of Sadowa. He had only to see the vengeance visited on the French for ignoring the principle of safety in numbers. And when presently he relaxed his grip, first on the 16th and again on the 18th [August], he twice came close to hazarding the whole campaign.[40]Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle: Mars – La – Tour 16 August 1870, page 101. .

On the 13th August Bazaine, apparently in charge but not in charge, was ordered by Napoleon to begin the retreat to Verdun, but demurred stating that “The enemy is approaching and will be observing us in such a way that a crossing to the left bank [of the Moselle] could be most unfavourable for us.” His preference was to offer battle at Borny, which was accepted by the Emperor, but only briefly, the debilitated monarch soon changing his mind when informed by the meddling empress that he could be outflanked to the north by the German armies of Steinmetz and Frederick Charles. Once again feeling obliged to conform to his wife’s military expertise, Napoleon again ordered Bazaine to commence the retreat: “You must therefore do everything you can to effect [the retreat] and if you feel in the meantime that you must undertake an offensive movement, you must make it in such a way that it does not impede the passage [to the left bank].”[41]Eugénie to Napoleon III. Paris 13 Aug. 1870. Napoleon to Bazaine. Borny 13 Aug. 1870. SHAT, Lb9, Metz, 13 -14 Aug. 1870. Quoted in, Wawro. Geoffrey, The Franco – Prussian War: The German Conquest … Continue reading

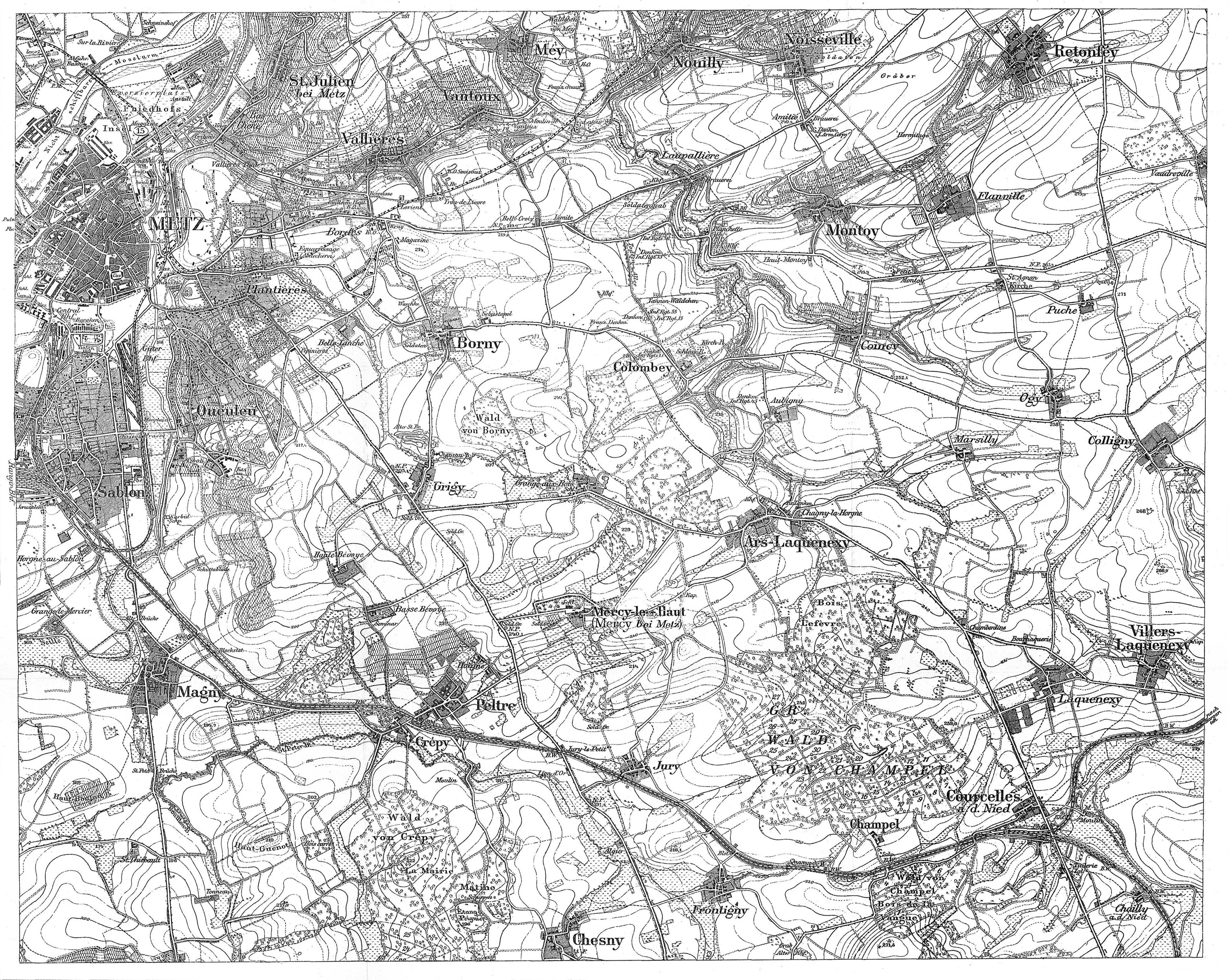

The Battle of Colombey – Nouilly.

On the 13th August Moltke, under the impression that the French army had already crossed the river, received information that the enemy was still on the east bank of the Moselle. Immediately he gave orders for Steinmetz to halt his forward movement and attempt to hold the attention of the French, meanwhile the II and III armies hooked north to fall on the French flank and rear around Metz[42] Elliot – Wright. Philipp, Gravelotte – St – Privat 1870: End of the Second Empire, page 46..

Moltke was working on the assumption that the French could be planning to launch an offensive, not realising that the enemy was in such a state of hesitation and indecision, owing to lack the lustre attitude of its commanders and the poor quality of staff work, that their only real strategy was the strategy of retreat. Nevertheless it would still be foolish to allow Steinmetz to bear the brunt of a sudden attack while Frederick Charles’s II Army carried on with his crossing of the Moselle. Therefore Moltke, on the evening of the 13th, altered his plans in case such an eventuality occurred. The II Army would now halt its advance, sending two corps to support Steinmetz while I Army remain in position to await events. On the 14th August German cavalry patrols probing forward in the early hours of the morning noticed large clouds of dust kicked up by the movement of masses of wagons and columns of marching troops, all heading their way to the Moselle bridges[43]Howard. Michael, The Franco – Prussian War, page 140 .

Upon receiving reports that the enemy was retreating, Major General von der Goltz, commanding the 26th Infantry Brigade (13th Division, VII Corps, I Army), had ridden forward to the high ground overlooking the Moselle valley from the east. Taking out his field glasses he scrutinised the French outpost positions along the Valliéres ravine covering their retirement and in the distance the snake like columns of retreating troops. ‘I knew,’ he wrote later, ‘that the sound of gunfire would bring strong support to the scene of battle,’ and once again, although showing initiative sadly lacking in his opponents make up, without bothering to consult his superior divisional commander for permission, Goltz ordered his brigade to attack[44]Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle: Mars – La – Tour 16 August 1870, page 105. .

Goltz was in for a nasty surprise, for although Ladmirault and Frossards corps were well on their way and Leboeuf’s 3rd Corps was beginning to pull out, upon hearing the outposts open fire he ordered an immediate halt, his troops returning to greet the Germans with a hail of bullets. Soon the chassepot dominated the valley and with French artillery also arriving on the scene Goltz’s advance was brought to a standstill. Even the two divisions of General Manteuffel’s I Corps which had come up in support were also pinned down by French rifle and artillery fire, despite bold attempts to get to grips with their adversaries. By 5:00 p.m. Ladmirault, also hearing the sound of battle, was also returning his troops to their former positions back across the Moselle and it looked as if the time was now ripe for a counter – attack which would have in all probability totally destroyed the impetuous German attacking forces well before any help could arrive[45]Howard. Michael, The Franco – Prussian War, page 142. .

Bazaine was, for the last time in his career, actually engaged on the battlefield, taking over command of Decaen’s division when that general was killed, and on these occasions he was in his element. He was slightly wounded in the shoulder by a shell fragment but still continued to give encouragement to his soldiers by his undoubted bravery and cool bearing under fire, but that was where his military talents ended. As far as any counter – attack was concerned Bazaine had no intention of committing any such rash undertaking, especially when recalling the Emperor’s emphasis on rapid retirement, thus another chance to do great damage to the enemy was lost.

The battle itself was indecisive but had delayed and disrupted the French retreat. French casualties numbered 3915 to the German 4620, proving that if nothing else, the battle of Colombey – Nouilly was no petty rearguard action. It was also to show how, even with victory within his grasp, Bazaine seemed to still consider that Napoleon was making the military decisions as commander of the army. When he visited the Emperor at Longeville to report on the day’s events the monarch had retied to bed and Bazaine gives the following account of their brief conversation:

The Emperor greeted me with his usual kindness. And when I explained my fears lest the Germans should cut in on my line of retreat, and referring to my wound asked to be relieved of my command, the Emperor, touching my bruised shoulder and broken epaulette, gracefully said: ‘It will be nothing, a matter of a few days, and you have broken the spell [Vous venez de briser le charme]. I await an answer at any moment from the Emperor of Austria and the King of Italy. Compromise nothing by too much precipitation and, above all things, no more reverses. I rely on you.’[46]Bazaine: Episodes de la guerre de 1870. Quoted in, Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle: Mars – La – Tour 16 August 1870, page 106 -107.

Thus the Emperor had made a military decision which Bazaine was only too happy to accept. Thereafter his actions can only be described as lacklustre verging on the indolent and the sluggish nature of the French formations around Metz came as a surprise to the Prussian King, William I, as he observed their tardy attempts at withdrawal from his observation point on the Noisseville plateau east of Borny on the 15th August. Now, apparently fogetting his former urgency in the matter of retirement, Bazaine wasted precious hours on the 15th travelling around Borny under a white flag, more concerned with the peasants robbing the dead and wounded on the battlefield than with the growing threat from the German forces closing in, indeed in itself a noble gesture, but not compatible with the task at hand. [47]Wawro. Geoffrey, The Franco – Prussian War: The German Conquest of France in 1870 – 71, page 147.

15th August.

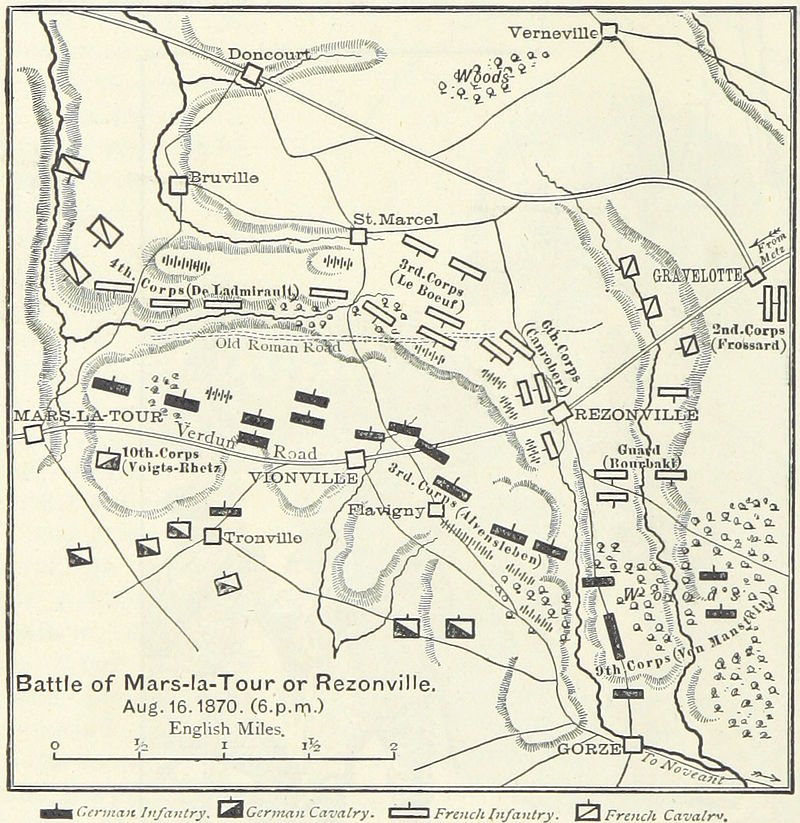

Bazaine’s orders for the continuation of the retreat to Verdun were not issued until 10:00 a.m. on the morning of the 15th August, at the same hour that German cavalry patrols were already wheeling around the Verdun road and were to show not only the Marshals tardy attitude in regard to making a swift and well conducted retirement but they also highlighted his inability to cope with the tasks involved in being army commander. The orders were:

- Left flank, 2nd and 6th Corps to take the Verdun road to Mars – la – Tour and Rezonville.

- Right Flank, 4th and 3rd Corps to march on Doncourt and Verneville.

- Imperial Guard, in the rear of the above formations at Gravelotte.

- One cavalry division to cover each flank of the retirement.

- Laveaucoupet’s division (2nd Corps), to remain as garrison in Metz.

The above instructions were not only totally inadequate in detail but also lacked any knowledge or understanding of the logistic planning involved in moving an army of over 160,000 men, plus thousands of horses and wagons. These problems were multiplied by the fact that along with the withdrawal of the army thousands of Metz citizens, together with their own means of transportation, were also fleeing from the city before the arrival of the German invaders. The single road from Metz to Gravellotte therefore became chocked with military and civilian vehicles, all jostling and pushing in an attempt to get forward. Some ease to the crush was achieved when the road split at Gravelotte, with one road going via Doncourt and the other to Vionville, but this moving column of humanity’s progress still crawled along at a snail’s pace; at 6:00 p.m. on the evening of the 15th August the French 2nd Corps had only got as far as Rezonville, while the 6th Corps was still some distance from Doncourt. Despite all this and the fact that Bazaine had been informed that his cavalry had made contact with the enemy north of the Vionville road, the blinkered visioned French commander did nothing, ordering a halt for the night.[48]Elliot – Wright. Philipp, Gravelotte St – Privat 1870, page 49. See also, Howard. Michael, The Franco – Prussian War, page 145 – 146.

As usual Moltke made his plans to suite the circumstances, or at least that is what he set out to do. At 5: 00 p.m. on the 15th he issued orders. Steinmetz’s I Army would move his VII and VIII Corps to the right bank of the Moselle, leaving I Corp at Courcelles – sur – Nied to protect the railway. Frederick Charles II Army would make ‘… a vigorous offensive movement,’ on the road from Metz to Verdun, by way of Frasnes and Etain. ‘The commander of the II Army is entrusted with this operation which he will conduct according to his own judgement and the means at his disposal, that is to say all of the corps of his Army.’[49]Quoted in, Ascoli. David, A Day of Battle: Mars – La – Tour 16 August 1870, page 108. [49] The III Army was drawn up in the line of Nancy and Bayou. [50]Moltke, The Franco – German War of 1870 – 71, page 25.

As David Ascoli states regarding Frederick Charles’s reaction to these instructions:

‘It was a tidy order, very precise and very Prussian. It presupposed every kind of presupposition. It assumed several false assumptions. And it came very close to bringing about a disaster.’

The orders given to Frederick Charles may have been precise but they were also rather vague since Moltke, even with all his meticulous attention to detail, was nonetheless guessing the exact whereabouts of the French army as being somewhere between Metz and Verdun. For his part Frederick Charles was also as much in the dark as to the exact position of the enemy. Even though his cavalry patrols had run into Forton’s French cavalry around Vionville he was still not sure if these were an advance guard or a flank guard for their main army. Among the Prussian cavalry scouting patrols was one commanded by the 36 year old Rittmeister Count (Graf) Oskar von Blumenthal. These troops were making their way in an anti – clockwise direction to the north of Metz, gathering information from villagers and peasants as they progressed. At Ars they came across a very jittery schoolmaster who nervously told them that he had just left Metz and that in his estimation “fifty thousand French troops had left the city the previous evening taking the route Langeville, Moulins, Ste Ruffine and the Route Imperial through Gravelotte, Vionville and Mars – la – Tour.” [51]I am deeply indebted to Henry von Blumenthal for allowing me to quote from his family notes regarding incidents occurring during the campaign and battles of 1870 -71. The Blumenthal’s had ten … Continue reading Upon receiving this information Frederick Charles issued his own orders on the evening of the 15th August for a continuation of the pursuit to the west towards the Meuse River by all his forces rather than following his original instructions for operations towards the north, as per Moltke’s original orders.

Michael Howard states:

The mistake was natural enough. By Prussian standards the French army, making full use of all the available roads, should certainly have reached the Meuse [River] by the 16th, and Frederick Charles’s error in directing his army too far west and thus outshooting Bazaine was more than pardonable than it would have been had he directed it too far to the east and missed him altogether. [52]Howard. Michael, The Franco – Prussian War, page 150.

As events turned out Frederick Charles’s unauthorised alteration to Moltke’s orders could have resulted in the whole Prussian/German war machine being either drastically knocked out of gear or even totally ruined. Even a prince of the royal blood should be expected to carry out the orders of his military superior.

The Battle of Vionville – Mars – la – Tour.

Early on the morning of the 16th August Napoleon bade farewell to Bazaine and set off on the road to Verdun, from where he would take the train to Chalons. At this time the French army was stationed as follows: around Rezonville 2nd and 6th Corps were encamped. The Imperial Guard was stationed to the rear of Gravelotte. One cavalry division was covering Vionville and two more observing the roads towards the north and west. The 4th Corps under Ladmirault was still struggling to get out of Metz. At around 9:00 a.m. German artillery began dropping shells into the French horse lines and camp of General Forton’s cavalry division around Vionville, announcing the arrival of the advance guard of General von Alvensleben’s III Corps of Ferderick Charles’s II Army. Forton’s troopers quickly responded, driving the advance guard back on Alvensleben’s main body, which was now beginning to concentrate on the high ground south of Rezonville.

Snaking their way up onto the plateau through the Gorze ravine Alvensleben’s troops were now confronted, not by a rearguard as expected, but by the whole of Frossard’s 2nd Corps spread out from Vionville across the fields to Rezonville and on as far as the Juree stream. In rear of these formations and plainly visible was the swath of white tents of the French 6th Corps to the north of Rezonville, with the compact masses of the Imperial Guard standing around Gravelotte, a sight to weaken the resolve of many a general. Not so von Alvensleben; seemingly unperturbed he at once ordered General Stülpnagel’s 5th Brandenburger Infantry Division to attack.

Advancing across the meadows on a broad front the company columns of Stülpnagel’s division, in which another member of the Blumenthal family, Georg, was deputy adjutant in Major General von Döring’s 9th Infantry Brigade, were mowed down by the massed rifle and artillery fire poured into them by Frossard’s 2nd Corps. Leaving a carpet of dead and twitching bodies on the ground, and mortally wounding von Döring. The Brandenburger’s fell back in some disorder and Alvensleben at last became aware that he had disturbed a hornet’s nest. The only thing for it was to smother the French position with artillery fire and by 11:00 a.m. he had assembled ninety cannon on the heights south of Vionville and Flavigny; the sheer volume of projectiles poured into the French lines cancelling out any thought of a French counter attack at this time. How intense this fire was is recorded by one of Frossard’s brigades who were lying in a reserve position in the grass well to the rear of the front line. This brigade alone lost sixty officers – thirty in each regiment – without coming into action, to say nothing of the devastation caused amongst the rank and file. Canrobert’s 6th Corps formations were also smothered in shells, one killing the military theorist and commander of the 10th Regiment, Colonel Charles Ardant du Picq. [53]Wawro.Geoffrey, The Franco – Prussian War: The German Conquest of France in 1870 -1871, page 154.

Meanwhile Alvensleben’s 6th infantry Division had been advancing towards Mars – la – Tour, which was already occupied by von Rheinbaben’s cavalry division, from there it had turned east towards Vionville, diving out the a regiment of French light infantry who were holding the village. Pushing on to Flavigny it was then halted and its artillery added to the German gun line which, by the evening would contain over 200 guns massed in an arc from Mars –la – Tour to the Bois de St- Arnould.

Even with the Krupp cannon dominating the battlefield, by 11:30 a.m.,von Alvenslaben’s situation began to look precarious to say the least. His one immediate support was General Voigts – Rhetz’s X Corps, marching to the sound of battle and approaching the field but still several hours distant. Now, despite the enemy artillery still causing consternation among his troops, should have been the time for a strong and forceful French army commander to have issued orders that would have given him a victory. Sadly Bazaine was not that man. Michael Howard sums up the dilemma and character of this brave but strange man:

To manoeuvre five corps, totalling 160,000 men, in an encounter – battle covering some thirty square miles, against an enemy of evident and indeterminate strength, would have tested the resources of a far abler general than Bazaine. As it was, Bazaine gave evidence once more only of his valiant physical courage and his incompetence as a general….He never for a moment thought of defeating the Germans. He made no attempt to clear the Verdun road. Instead, he was obsessed with the danger to his left flank – with a possible thrust which would cut him off from his base at Metz. With the fortress at his back he could not come to great harm; but to leave it and advance, even victoriously advance, was to abandon safety and place in hazard the army which, Bazaine must now have realised, he was quite unfitted to lead. [54]Howard. Michael, The Franco – Prussian War, page 155.

At noon Canrobert had brought up his reserve artillery and placed it in battery along the line of the old Roman road running in front of Villers – aux – Bois, from where they now began bombarding Alvensleben’s left around Vionville; as these guns bucked into action Leboeuf ’s 3rd Corps came plodding towards the battlefield heading towards St Marcel while, although at the moment still at some distance from the battlefield but marching in the direction of Mars – la – Tour, came General Louis de Ladmirault’s 4th Corps. These formations, together with the Imperial Guard, gave Bazaine an overwhelming superiority in numbers, but still the French army commander thought of nothing other than standing on the defensive. Indeed, the orders coming from Bazaine’s headquarters in the Maison de Poste at Gravelotte to the Guard commander General Bourbaki stating, “Assure the retreat,” and “Detach a division to cover the Bois d’Ognons and the Ars ravine,” only confirmed how obsessed he was with clinging on to the fortress of Metz, seeing phantom German formations coming to turn his left flank, ‘… ignoring the right flank, where victory might have been cheaply won, he concentrated on banishing the faintest shadow of defeat from the left; piling up around Rezonville a huge concentration of troops…to repel the “ enemy masses” which he hourly expected to see emerging from the ravines to the south.’ [55]Ibid, page 155.

Frossard had not made things better when, having his flank pushed back by the rapid assault of the Germans, plus one of his division commanders killed, he sent an urgent appeal for help to Bazaine. Although there was infantry aplenty still uncommitted Frossard, for some strange reason, asked for cavalry to restore the situation, a request that Bazaine immediately complied with by sending a regiment of the Guard cuirassiers to bolster the lancer regiment Frossard already had to hand. When the colonel of the cuirassiers objected strongly to Bazaine about his orders, stating that it went against the usages of war to send cavalry to attack unbroken infantry, Bazaine replied, in what Michael Howard calls, ‘ that unfortunate French talent for the unsuitably dramatic,’ “It is vitally necessary to stop them: we must sacrifice a regiment!” [56]Howard. Michael, The Franco – Prussian War, page 156. Bazaine’s statement is taken from, Guerre Metz II 294 – 6. The relevant Docs. Annexes however ( page 478) make no mention of this protest. Once again the cavalry was called upon to save the situation, and once again its sacrifice only served to hammer home the fact that their original role on the modern battlefield had passed. Advancing with a splendour that was deserving of a better fate, the two regiments soon lost their alignment over the rough ground and then were brought down in bullet riddled heaps by the steady fire of enemy infantry standing in front of Flavigny. Those that managed to escape milled around the battlefield until they were driven off by a counter attack by General von Redern’s cavalry brigade. [57]Ibid, page 156.

It was now passed mid – day and although being informed by Voigts – Rhetz’s chief of staff, Colonel Caprivi, that X Corps was on the way, von Alvensleben, his infantry reserve now all committed saw that, although the French had been temporarily held, it was only a matter of time before they put in an annihilating attack against his weak left flank. To shore up his line and slow down the enemy Alvensleben, like Frossard, now turned to the cavalry. “Von Bredow’s Death Ride” was one of the last great cavalry charges in history and the cost was commensurate, but like the old adage that if you buy enough tickets in a lottery you are bound to win something, it did work, at least in causing consternation in the French ranks.

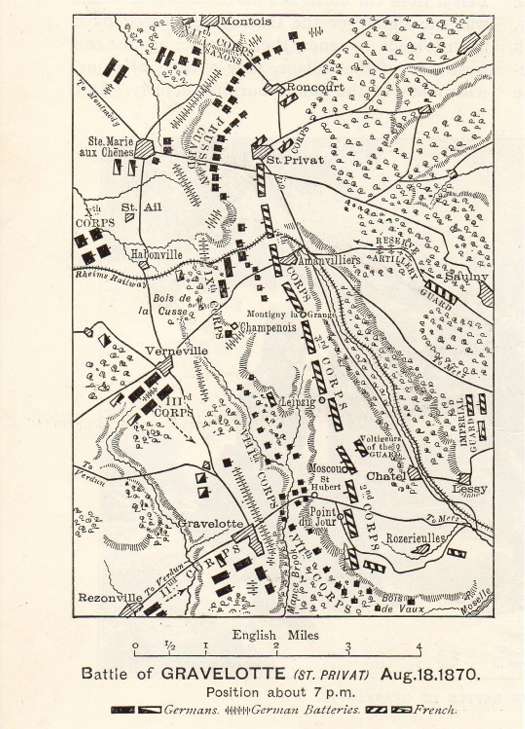

Born in 1787 Bredow was seventy three years of age when he climbed onto the saddle of his charger to lead his brigade into battle and into history. His command consisted of three squadrons of the 7th Cuirassier Regiment and three squadrons of the 16th Uhlan (Lancer) Regiment, a total of 804 officers and men. Upon receiving the order to charge von Bredow did not demure but, like a well trained cavalry general should do, did take his time in preparing for the attack. He rode out to study the ground and thereafter detached a squadron of cuirassiers and a squadron of Uhlans from each regiment to cover his left flank towards the Tronville wood. After briefing his regimental commanders at 2:00 p.m. and then pronouncing “ Koste es, was wolle” ( It will cost what it will), he ordered the advance.