July 3rd 1866

Introduction

It is not difficult to understand why the Battle of Königgrätz in 1866 is still considered to be one of the decisive battles of the modern era. It has even been suggested that the rise of Adolf Hitler could not be explained without the events of 1866. While this may be a debatable supposition, the battle and the campaign demonstrated the power of Prussian science and military art.

The Seven Week’s War, as the campaign in Bohemia became popularly known, was the first occasion in which the steel-rifled cannon and the breech-loading rifle were seriously put to the test [1]The Danish War of 1864 had seen the Prussians on campaign with their breech-loading rifles, but no real understanding of its full potential was realized, both by the Austrians, or the various … Continue reading. Likewise, the use made of the electric telegraph and railways pointed to the future importance of communication and transport. As a battle alone, with no frills attached, Königgrätz (sometimes called Sadowa) was by far the largest battle fought in Europe during the 19th century. Well over 450,000 men were on the field in an area of less than eight square miles. Within this space the Austrian artillery maintained a rate of fire seldom witnessed before, portending the massed barrage fire of the Great War of 1914-1918. The Austrian cavalry, meanwhile, despite the fearful toll exacted by the Prussian needle gun (named for its needle-shaped firing pin), did indeed prove itself a most disciplined and able force in delaying the advance of the victorious Prussian infantry; but the days of the old fashioned cavalry regiments were clearly numbered when set against rapid rifle fire.

Background.

Prussia had emerged from the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 as the weakest of the five great European powers (England, France, Austria, Russia and Prussia). She seemed far inferior to Austria both in military strength and total population. By 1859, however, the squeaking cogs of the Austrian military machine had been heard by the Prussian General Staff in Berlin. Perhaps what the small monarchy of Piedmont-albeit with French assistance-had recently done for a unified Italian cause might also be achieved by a German confederation under Prussian control?

To this end, Count Otto von Bismarck, first minister of Prussia, addressed all his efforts. From the moment he came to power in 1862 until the outbreak of hostilities in 1866, Bismarck pursued a course whose main objective was securing Prussian domination over Austria and the smaller German states. His policy of aggrandizement was based largely on a strong military program. For Bismarck, as it was for the Prussian military theorist Karl von Clausewitz, war was an extension of state policy by other means. The crushing of democratic Prussian liberalism in 1862 had left the way clear for a confrontation with Austria

A situation now arose that gave Bismarck his chance to inaugurate a series of diplomatic manoeuvres that would nudge Austria along the road to war. For some years, the two duchies of Schleswig and Holstein had been a thorn in the side of both Austria and Prussia, with the kingdom of Denmark claiming sovereignty over both. In 1864, Austrian and Prussian troops under the overall command of Austria invaded the duchies. In January of that year the Danes were defeated and their king, Christian IX, was compelled to sue for peace. By the terms of the Treaty of Vienna, the Danes ceded their rights over both Schleswig and Holstein. The two duchies were placed under the control of Prussia and Austria, Holstein going to Prussia and Austria administering Schleswig.

Such a condominium between Austria and Prussia could not be expected to work without friction. By the summer of 1865, the two powers were on the brink of war, but Bismarck was not ready to enter a conflict at this time-a convention of sorts was arranged and a deal struck at Gastein in Austria, to paper over the cracks and allow a breathing space, during which both sides began to organize their military forces for the showdown that was bound to come.

Bismarck made full use of the lull to win over the Prussian King Wilhelm I and his advises. He also managed to talk round Prussian Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke, who was cool towards an all-out war with Austria, by promising him an alliance with Italy that would divert some of the Austrian forces. The Italians agreed to this alliance provided that in event of a Prussian victory, the province of Venetia would be handed over to them, and that the war with Austria would commence within three months after April 1866. The Mexican war of 1865 had been such a disappointment to the French Emperor Napoleon III that French neutrality was won over by a shadowy assurance of some form of compensation from Bismarck when he met the Napoleon at Biarritz. Bismarck also used his diplomatic skills to neutralize Russia. At last, he could set his sights on the confrontation he had so long desired and so artfully delayed.

On June 1st, 1866, Austria announced that the settlement of Schleswig and Holstein should be entrusted to the Germanic Confederation, within which she held control. Whereupon Prussia declared that Austria had broken the Convention of Gastein, and she claimed control over both duchies. On the 7th of June, General Edwin Rochus Freiherr von Manteuffel led a Prussian force of 12,000 troops into Holstein, forcing a much weaker Austrian contingent to retire before him. Austria promptly demanded from the various states of Germany a declaration against Prussia. On the 14th, the motion was carried by nine votes to six-war with Prussia had come about.

The conflict that followed would show how little the Austrian high command had learned from the catalogue of mistakes made during the 1859 Italian campaign. Although Austria had by now made an attempt to remedy the discrepancy between her strength “on paper” and the real numbers of trained men actually available for a war on two fronts, in tactics and troop control Austria persisted in the archaic methods of a bygone age.

The Opposing Armies.

Theoretically, the Austrian army, which was made up of conscripts, had 10 corps of 83,000 men each. This mass of manpower was, however, a long time in forming from its cadres onto the battlefield. Further problems arose with their Italian regiments who had to be moved away from their recruiting areas for fear of desertion once it was understood that Italy had thrown in her lot with the Prussians. Moreover, while Prussia had the Landwehr, Austria had no militia to provide a backup service in functional or fortress duties. Worse yet, certain professions within Austrian society were exempt from military service-a substitute could be hired to serve in another man’s place.Because of these problems, plus deductions for any sick, labours and security forces, Austria could only place 320,000 men in the field; of these, only 240,000 would be able to operate against Prussia, while 80,000 were needed on the Italian front. The army was divided into 10 corps, three of which were assigned to northern Italy. Austria had no divisional system except in the cavalry, the infantry being formed into brigades of two regiments and a Jäger battalion. A corps had four such brigades, plus a regiment of light cavalry. The brigades manoeuvred in dense battalion columns of some 1,000 men each, relying on the mass attack with the bayonet. The Austrian army was well served with artillery, her rifled field guns being complemented by a section of Raketengeschütz, or rocket batteries, which never seem to be considered by many historians writing about the campaign.

|

|

Prussia had nine army corps, each comprised of two infantry divisions and an artillery reserve. Each division had four infantry regiments, four batteries of artillery and four squadrons of cavalry; in all, some 15,000 men, 600 horses and 24 guns. Unlike the Austrians, whose infantry was armed with the Lorenze muzzle-loading rifle, the Prussians enjoyed the benefit of the breech loading Dreyse needle gun, which could fire five rounds per minute and could even be fired from the prone position, thus reducing the enemy’s target. When advancing to the attack, battalions moved in parallel columns, by companies. Both Prussia’s cavalry, and to a large extent it artillery failed to play a major role in the campaign. The latter suffered from a combined lack of funds and bad administration, and although the steel breech-loading cannon was used in small numbers on the battlefield, the problems with the breech remaining tightly sealed after only firing a few rounds caused it to be regarded with caution by artillery commanders. The cavalry was simply neglected, being used in the main for duties behind the lines instead of for intelligence gathering. At the outbreak of hostilities Prussia could muster more than 350,000 men, of which 250,000 were set against Austria. Prussia could also call upon large numbers of reserves if the need arose, an element totally lacking in the Austrian system.

The Opening Moves.

|

|

Prussia’s Chief of Staff von Moltke, placed in command on June 2nd 1866, with only the Prussian king to answer to, was well aware of the Austrian lead in mobilization, but he made good use of Prussia’s railway system to mass his troops well forward in an arc extending from Silesia to Saxony, a distance of some 275 miles. When that concentration was complete, the three Prussian armies stood as follows: The Army of the Elbe under General Karl Eberhard Herwarth von Bittenbfeld, approximately 45,000 strong, around Halle and Zeitz on the Saxon border; the First army, 94,000 men commanded by Prince Friedrich Karl, at Torgau and Kottbus; the Second Army, including the Guard Corps, in all some 120,000 men commanded by the crown prince of Prussia, Freidrich Wilhelm, at Landshut and Reichenbach, Silesia.

The Italian war of 1859 had shown the Emperor Franz Josef that he was not the man to take charge of Austrian troops at the front. He therefore chose the popular Feldzeugmeister (Field Marshal) Ludwig August von Benedek, who was considered by many, after his exploits during the Battle of Solferino (1859), to be Austria’s best field commander since Josef Radetzky. The only person who did not share this view was Benedek himself. He knew his limitations and was quite out of his depth fighting a war in Bohemia, far from his old campaign grounds in Italy. Try though Benedek did to decline the post, the emperor was adamant. Benedek reluctantly accepted his fate. Not wishing to be seen as the aggressor in the eyes of Europe, Austria adopted a plan based on a defensive attitude in both diplomatic and military terms. The memorandum for war was therefore prepared by a former chief of the topographical bureau, Brigadier General Gideon Ritter von Krismanic, for no other reason other than he apparently had some knowledge of the geographic defensibility of Bohemia. That supposition not only proved to be quite unfounded but also became something of a joke, since all the maps of the region supplied to the Austrian General Staff were out of date. Kismanic’s plan was based on a defensive position that was centered around the fortified town of Olmutz in Moravia and was intended to protect Vienna. Unfortunately for Austria, the decision to go straight onto the defensive was tantamount to throwing away any initiative they had gained by their advanced mobilization.Even so, the position of the Austrian corps around Olmutz still could have proved favourable under stronger leadership. But Benedek showed he had no idea how to use his central position, unlike a certain Corsican-born general some 60 years before who used such situations so effectively.

On June 15th, secondary forces under the Prussian General Vogel von Falckstein cut off the Hanoverian state’s army and isolated Bavaria, effectively knocking two of Austria’s allies out of the war. On the 16th, the Prussian General von Bittenfeld’s Army of the Elbe crossed into Saxony. Upon its approach, the Saxon crown prince, Albrecht, withdrew his army of some 25,000 men across the Iser River, there linking forces with the Austrian I corps under General Eduard Clam-Gallas. Benedek now placed Crown Prince Albrecht in command of the I corps as well his own Saxons, and ordered them to take up a defensive position in front of the town of Gitschin. The Austrian commander in chief would concentrate his forces at Josefstadt and march to their aid. By June 29th, however, no other Austrian troops had arrived, and the Saxon prince had to fight a very heavy engagement against Friedrich Karl, from which he managed to extricate himself with great skill but heavy losses.

Meanwhile, Benedek still believed that the Prussian Second Army was moving northward and was therefore not a problem. After the border battles at Nachod, Trautenau and Eypel, however, the chance to catch Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm’s army as it debouched through the mountain passes only emphasized earlier opportunities Benedek had let slip by. As the official Austrian account of the war says:

“If, instead of waiting until the last moment, the IV and VII Corps had been sent off a day or two earlier, and the II Corps, which was nearest to Josefstadt, had led the march instead of bringing up the rear, the concentration round that town could have been effected far more rapidly. Even if a few brigades of infantry had been sent into Bohemia by rail with orders to observe and close the frontier defiles, they could have delayed, even had they been unable to check, the advance of the Prussian Second Army. In doing so, they would have made it possible for the principle Austrian forces to have fallen upon the army of Prince Friedrich Karl and crushed it with superior numbers”.

Indeed, at Trautenau, Lieutenant Field Marshal Ludwig Freiherr von Gablenz’s Austrian X Corps attacked the Prussian I Corps with such spirit that it drove the Prussians back across the mountains. However, Gablenz alone could not repeat his success and was in turn defeated at Prausnitz by the Prussian Guard Corps. Only on June 30th did Benedek realize the full error of his dispositions and telegraph his emperor to sue for peace. Franz Josef had no such intention. He told Benedek that he had every confidence in his ability, and that he had sent one of his personal officers to the front to view the situation. The result was that Clam-Gallas was removed from his command for his failure at Gitschin, and Field Marshal Alfred Freiherr von Henikstein, Benedek’s chief of staff, was replaced by General Baumgarten. He did not arrive at army headquarters until the very day of the Battle of Königgräz, a delay confusing the situation still further by giving the Austrian’s two chief’s of staff on the field during the battle. Still, Benedek saw the possibility of a defensive battle being fought on the high ground between the Bistritz and the Elbe rivers. His confidence began to return as he regrouped his army for the decisive battle that was to come.

|

|

The Battlefield.

The Bistritz River is no more than a small tributary of the Elbe. On its east bank the ground rises in a series of slopes and undulations that soon form a small chain of hills that overlook the approaches to the river from the west. These hills had been strongly fortified with abatis and earthworks and ran from Problus northward to the villages of Lipa and Chlum. From there the ground dipped and then rose again to the hills of Maslowed and Horenowes, falling away again to the Trotina River, on Benedek’s right flank. Two tight clusters of woodland, each approximately 1,600 meters square each, the Holawald and the Sweipwald, stood in front of the villages of Lipa and Maslowed to the north; and in the south, at Neu Prim and Problus, two more woods, the Steziek wood and the Briza wood, abutted from the main Austro-Saxon position itself.For two days before the battle, Benedek’s inspector-general of artillery, Archduke Wilhelm of Austria, had reconnoitred the area, positioning his artillery so that it had a clear field of fire and marking the ranges for his excellent rifled cannon. On the high ground at Lipa and Chlum, many batteries were placed in tiers overlooking the approaches from Sadowa and the Bistritz Valley. There, on July 3rd, 1866, the fate of Germany was to be decided.Benedek’s forces were divided into four groups. In the centre, at Chlum-Lipa, III Corps an X Corps held the line-in all, some 44,000 men and 134 guns. Both corps had units well forward near the Sadowa bridge to dispute the crossing On the left, the Saxons and VIII Corps, comprising of 40,000 men and 140 guns, held the sector composing of Techlowitz, Neu Prim, Ober Prim, Nieder Prim and Problus, also with outpost lines pushed well forward towards the Bistritz crossing points. On the right- and by far the weakest position on the field-stood IV Corps and II Corps with 55,000 men and 176 guns, between Chlum and Nedelist. Entrenchments had been dug and massive gun emplacements constructed along the ridge that ran between these two villages, but they were themselves overlooked a little farther north by the heights of Maslowed and Horenowes. Both flanks of the Austrian position were covered by a cavalry division. Between Rosberitz and Wsestar, I Corps and VII Corps, together with the heavy cavalry and artillery, formed a reserve mass of 47,000 infantry, 11,435 cavalry and 320 guns.

The weakness in Benedek’s position, a rough semicircle with both flanks resting on the Elbe River, was that it would be difficult to meet an enveloping attack, since the Austrian main line of retreat ran along the Sadowa-Königgräz highway and was therefore susceptible to being cut. Quite possibly the Austrian commander did not expect that the Prussian Second Army would be able to join the battle, thinking that he would be confronted by only the two other Prussian armies in a frontal attack against his prepared positions? Owing to a total lack of reconnaissance on their part, the Prussians did not know the whereabouts of the Austrian army, and there was some consternation at headquarters as to whether Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm would arrive in time, should Benedek make a stand. Even so, Moltke managed to keep a cool head, although suffering from a heavy cold. He sent out patrols, which on 2nd July discovered the Austrian position. Then, orders were dispatched to the Second Army urging all possible speed in descending upon the Austrian right flank. The Prussian VI Corps and the Guard Corps divisions which were nearest to the Austrians, still had no hope of reaching the battlefield until midday on the 3rd July; the other units of the crown prince’s army would not arrive until much later. It appeared that the Prussian Elbe and First armies would have to fight alone for at least four or five hours against the full weight of Benedek’s army.

The Battle.

The morning of July 3rd dawned grey and damp as the Prussian units moved forward towards the Bistritz River line. The principle objective, as far as Friedrich Karl was concerned, was to drive in the Austrian outposts and, after establishing a firm hold on the right bank, to push on into the heart of Benedek’s position. Only after great difficulty did Moltke persuade Friedrich Karl that his task was limited to pinning down the enemy until the Second Army came in against the Austrian flank. To that end, at 7 a.m., Moltke ordered the 8th Division to move forward towards Sadowa while the 3rd and 4th divisions, keeping in line with the 8th, advanced to the south of the main highway, against Unter-Dohalitz and Mokrowous. The 5th and 6th divisions followed in the wake of the 8th. Between these forces, the combined cavalry corps kept in contact with the Army of the Elbe. Out on the left, Lt. General Eduard Friedrich von Fransecky’s 7th Division moved against the village of Benatek, using a single cavalry division to keep in touch with the rest of the First Army. A good deal of discretion was given to the commander of the 7th Division, an enormous responsibility really, since ha had to contain the Austrian right until the crown prince arrived on the field. On the Prussian right, Bittenfeld’s Army of the Elbe reached Alt Nechanitz at about 8 a.m., marching in a cold mist and drizzling rain that had been falling since dawn. During that time, the Austrian and Prussian artillery had been exchanging shot for shot, with neither as yet doing any great damage. At Nechanitz, the Saxon and Austrian outposts fell back in good order to their main positions around Problus. From there they poured a destructive fire into the Prussian ranks as the latter emerged from the smoke of battle. Bittenfeld showed no great hurry in getting his troops across the river, believing that he would be isolated should the Austrians mount an offensive against the Prussian centre. Therefore, by 10 a.m. Brig. General von Schöler’s advance guard of some seven battalions, finding itself without support, was forced back by a spirited counterattack from Nieder Prim to the Hradek-Lubno ridge, led by the Saxon Life Brigade.

In the centre, the 8th Division cleared Sadowa of its defenders at 8:30 a.m., while on the right the 4th Division attacked Unter-Dohalitz, and the 3rd Division pushed into Mokrowous. Like the Saxons, the Austrians fell back in an orderly manner to the high ground. Almost all the villages along the Bistritz were now on fire-the smoke and haze made it impossible for the Prussian’s to see their enemy clearly, while the defending Jäger battalions poured a continuous fire at the mere sound of the advancing columns. The 3rd Division also now came under fire from part of the massive battery of guns ranged from Langenhof to Lipa, halting the Prussians for almost four hours. The 3rd Division’s troops were ordered to find what cover they could until the enemy battery could be outflanked. The 8th and 4th divisions, after advancing from the river line, found that they, too, were prey to a good number of the Austrian guns. Forced to use the trees of the Holawald and the crumbling ruins of Ober-Dohalitz for protection, they received such a pounding that some units made desperate yet futile attacks against the bristling ridge of cannon. Whole battalions dashed forward, only to be cut down in swaths by the measured range of Austrian fire.

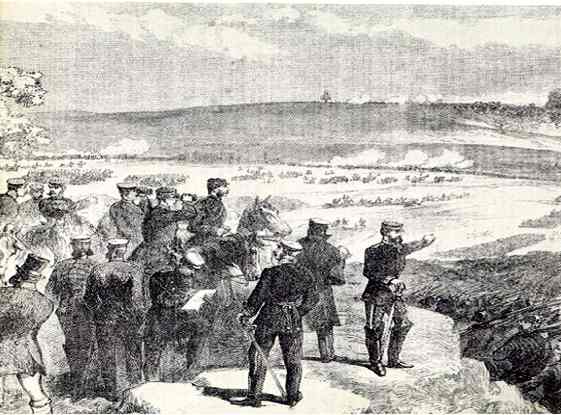

The royal headquarters had by this time moved to the Roskosberg to the rear of Sadowa. From that vantage point the King of Prussia had a good view of the punishment his two divisions were receiving in the Holawald. Seeing some bloodied battalions retiring, he rode forward, shouting that he was going to lead them back again so that they could “fight like brave Prussians.” Staff officers tactfully managed to restrain their monarch, but by 10:30a.m. the losses incurred by the 8th and 4th divisions were mounting significantly, without any obvious relaxation in the Austrian barrage. The 7th Division, too, was receiving a tremendous hammering on the left. The dilatory behaviour of the commander of the Army of the Elbe found no counterpart in Fransecky’s makeup. His 7th Division was to perform prodigies of valour and improvisation as it took on almost one-quarter of the Austrian army. As already mentioned, the Austrian IV Corps and II Corps were overlooked from the north by the heights of Horenowes. Both corps commanders had decided, with the approval of their respective chiefs of staff, to move their front 90 degrees to the west, taking station along a line extending from Chlum and Maslowed, and leaving only five battalions and a light cavalry division to guard the approaches from the north. After he had sent out couriers to the crown prince’s Second Army requesting urgent assistance for his right flank, Fransecky’s troops took the village of Benatek at 8a.m. Consolidating their position there, they then debouched from the village in the direction of Maslowed. Suddenly they came under heavy fire from the Sweipwald wood, which had been presumed clear of enemy units. The Prussian advance guard under Colonel von Zychlinski now halted its forward movement until the 26th and 66th regiments came up to join it. Then, at 8:30 a.m., Zychlinski threw the combined force, some 5,000 men, against the Sweipwald, pushing the defenders back up the wooded hillside toward Cistowes. There, Lt. General Tassilo Graf Festitic’s IV Austrian Corps had recently come into line after moving from the right flank. In a series of counterattacks, Festitic’s battalions suffered appalling casualties as they advanced in column formation against the rapid fire of the Prussian needle guns. By 9:30 a.m., three full brigades had been used up, to hardly any avail. Festitic’s himself was wounded, but his second- in- command, Lt. General Anton von Mollinary, rather than forming a defensive line at Maslowed, was even more determined to evict the Prussians from the wood. Calling on the assistance of Lt General Carl Graf Thun von Hohenstein’s II Corps, Mollinary threw still more troops into the corpse-littered wood.

At 10 a.m., Brigadier General Emerich Fleischhacker’s Austrian brigade went in with the bayonet, drums beating and flags unfurled. By now, all the Prussian 7th Division’s reserves had been used up in holding back these suicidal attacks, and Fransecky sent for help from the 8th Division on his right. Two fresh regiments arrived just in time to pour a hail of bullets into the tightly packed Austrians, driving them back once again to the edge of the wood. Waving his sword like a dervish, Mollinary sent in yet another full brigade. These fresh troops, under Colonel Carl von Pöckh, drove into the Prussian front and left flank, forcing them, in turn, to fall back to the farthest outskirts of the wood. It now seemed as if one final push would unhinge the entire Prussian left flank and send it back across the Bistritz in rout.

But it was not to be. At 11 a.m., the right flank of Pöckh’s brigade came under a tremendous fire from the direction of Wrchownitz. In a matter of minutes the brigade commander was dead and more than 2,000 of his men were killed or wounded. The Prussian Second Army had arrived on the field.

|

|

The Prussian 1st Guard Division had marched from Dobrawitz as soon as its offices had received Fransecky’s appeal for help. They were now descending the low hills in front of Wrchownitz, catching the Austrians in flank as they attacked the Sweipwald. Not far to their rear came the 2nd Guard Division, its advance guard already near Zizelowes.Away to the south-east, the Prussian VI Corps under General von Mutius was heading straight for Racitz, the 11th Division on the right of the Trotina River and the 12th Division on the left. Both divisions were as yet unblooded in battle, but their men were eager to prove themselves in action before the arrival of their more experienced brothers in V Corps, which was still some distance to the rear.

With the annihilation of Pöckh’s brigade as a fighting force, and the imminent arrival of the entire Prussian Second Army, Benedek realized the full implication of the errors made by Mollinary and Thun in moving their corps from their prepared positions. True that during the fighting in the Sweipwald the Austrian commander had been preoccupied with the vision of a counterattack against the whole Prussian First Army, but he should not of cancelled an order to Lt. Field Marshal Wilhelm Freiherr von Ramming’s VI Corps to fill the gap on the right. It was now far too late. All Benedek could do was order the IV and II Corps to fall back to their original positions between Chlum and Nedelist. That proved not only difficult, owing to the amount of commitment given to the fighting in the Swiepwald, but also fatal to the morale of troops who had been under the impression they were winning the battle. The result was that the whole force fell back in great disorder, taking a good part of Thun’s corps along too. Thun himself seems to have given up the battle as lost and marched two full brigades towards the Elbe bridges.Over on the Prussian left wing, the Army of the Elbe was, at last, making some headway against the Saxons. At 3 p.m. the Prussian 14th and 15th divisions captured Problus and Nieder Prim. The Saxon crown prince, seeing his position about to crumble, sent in a strong counterattack to gain time for the retreat of his remaining forces. Once again Bittenfeld fell into a torpor, and after diving back the Saxon attack, the Army of the Elbe halted. Bittenfeld still had the fresh 16th Division at hand, but was content to consolidate his position around Problus. Thus, the chance of a double envelopment of Benedek’s army was lost.The right flank of Benedek’s position was about to fall apart in any case. His troops had been forced out of Maslowed, and the high ground to the north was in Prussian hands. Along the lower Trotina River, the five battalions of Henriquez’s brigade were driven back, while the Austrian gun line had also retired to a position between Langenhof and Wsestar. There the Austrians formed a line containing more than 120 cannon.The commander of the Prussian 1st Guard Division, Lt General Friedrich Hiller von Gärtringen, now saw that the hinge of the whole Austrian position rested on the village of Chlum and its high ground. I the village itself, the Austrian brigade of Brigadier General Carl von Appiano had, as yet, not become aware of the tide that was about to break over it. Than, when it did, his troops were forced out of the village and streaming back toward the rear, taking their reserves along with them. One lone cavalry battery, under Captain August von der Groeben, endeavoured to stem the Prussian advance. Its first salvos were answered by such a crippling enemy fire from all sides that with the space of five minutes he was killed, together with 53 men and 68 horses. Groeben is little remembered today. A crude monument erected on the spot bears the poignant inscription “The Battery of the Dead.”

By 3 p.m. all Benedek could do was order a general retreat. Mollinary and the Austrian VI Corps commander, Field Marshal von Ramming, both begged their chief to counterattack, but he had by now lost all control over the battle. At 3:15 p.m., without a direct order, Ramming took it upon himself to send forward two fresh brigades to retake Rosberitz and Chlum. At the same time, the Austrian guns at Langenhof redoubled their fire to cover the attacks.

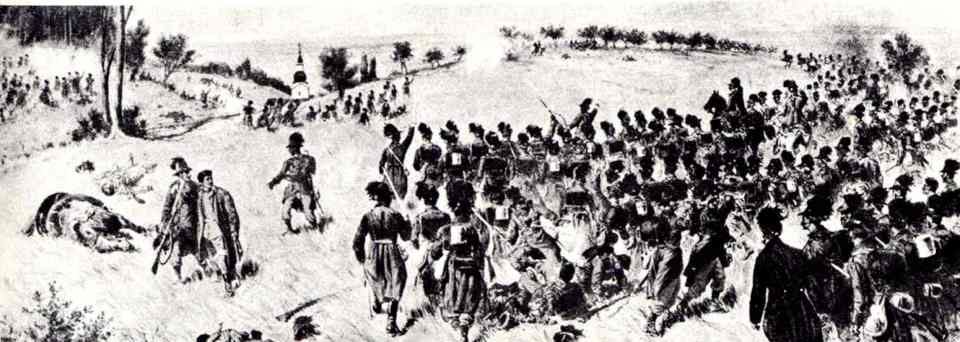

In a fierce fight, the Prussian 1st Guard Division was forced out of Rosberitz and back to Chlum, pursued by the bloodstained battalions of Brigadier General Ferdinand Rosenzweig von Dreuwehr’s Austrian brigade. Three guns were captured, but the only thing their valiant counterstroke achieved was to bring still more Prussian units to the assistance of the 1st Guard Division. The 2nd Guard Division now came into action, together with elements of the Prussian I Corps. These units, joined in a well-timed attack by the 11th Division (from the direction of Nedelist), smashed into Rozenweig’s brigade and sent it reeling back in its turn toward Rosberitz. There the Austrian I Corps and VI Corps made a gallant effort to contain the Prussian masses, and only after suffering immense losses were they gradually forced back. The battle was now firmly in Moltke’s pocket. Only the fire from the Austrian artillery delayed the victorious Prussians as they moved ever nearer to cutting the Sadowa-Königgrätz road. It was now, too, that Benedek played his last card by sending in the cavalry divisions of Brigadier General Carl Graf Condenove and the prince of Holstein to attack westward and break up any pursuit by Friedrich Karl’s First Army.In the charges and counter charges that followed, the Austrian cuirassiers, uhlans and dragoons not only threw the Prussian cavalry into disarray and made pursuit by them very unlikely; they also held back the Prussian infantry for more than half an hour. The cost, however, was terrible: 64 officers, 1,984 men and 1,681 horses.

The cavalry attacks, plus the bloody attacks sent in by the I Corps, were successful in containing the Prussian advance and allowing the retreating Austrians to reach the Elbe. At 9 p.m., the last shots were fired by their horse artillery. Moltke now halted the carnage, and in the gathering dusk his men sank to the ground exhausted.

Panic reigned in Königgrätz, where the Austrians became jammed together in one chaotic mass of men, wagons and horses. The only luck that Benedek had during the day was that no Prussian pursuit was forthcoming.

The losses incurred by the Austrians and Saxons amounted to 1,372 officers and 43,500 men killed, wounded or missing, of whom almost 20,000 were taken prisoner. The Prussian losses were much lower: 360 officers, 8,812 men killed, wounded or missing, more than half of whom came from the First Army. Moreover, the disproportionate difference in the wounded and missing between the two antagonists was increased by the Austrians, who never signed the Geneva Convention. Consequently, their medical personnel, who were unprotected by the Red Cross and classified as combatants, withdrew with the rest of the Austrian army, thus leaving many men on the field who could otherwise have been administered to rather than being left to bleed to death or to be captured.

The Austrians now decided that to carry on the struggle would be futile, and a five-day armistice was arranged, subsequently extended to August 2nd. The final peace terms were signed at the Blue Star Hotel in Prague on August 23rd. From that time until the outbreak of World War I, Prussia would be the undisputed head of the German confederacy-and one of the most awesome military powers in the world.

Graham.J.Morris January 2003.

Bibliography.

| Craig. Gordon A., | The Battle of Königgrätz, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1965. |

| Craig. Gordon A., | The Politics of the Prussian Army, 1640-1945, paperback edition, Oxford University Press, London, 1964. |

| Hughes.Daniel J., | Moltke on the Art of War, paperback edition, Presidio Press, Novato, CA, USA, 1995. |

| Maguire, Miller T. and Herbert. Captain William V., | Notes on the Campaign between Prussia and Austria in 1866, paperback edition, Helion and Company, London, 2000. |

| Malcolm, Lieut-Col. Neill, D.S.O., | Bohemia. 1866,Constable and Co. Limited, London, 1912. |

Acknowledgments.

I would like to thank the Herresgeschichtlichen Museum in Vienna for allowing me permission to take the photographs of Austrian uniforms. A comprehensive range of works dealing with the Austrian Army is available in “Band” from 1 through to 12 from the Militärwissenschaftliches Insititut Wien.

Thanks also to Heritage Sites in Europe, Czech and Slovak Republics, for the Königgrätz Memorial photograph. Erwin’s Military Gallery, for Austrian and Prussian campaign medals. Michael Wenzel, who has been of great assistance in supplying the information on Austrian Rocket Batteries-thanks Michael! And yet another hearty thank you to Dr Bob, without whose help and expertise in web page construction I would still be floundering around in the dark-thanks Robert! Finally, a warm and much loving thank you to Louise, who never interferes, but always seems to be there when needed.

Order of Battle of The Prussian Army.

| Commander-in-Chief: | His Majesty the King of Prussia |

|---|---|

| Chief of Staff: | General von Moltke |

| Inspector-General of Artillery: | Lieut.-General von Hindersin |

| Inspector-General of Engineers: | Lieut.-General von Wasserschleben |

| 1st Army | |

|---|---|

| Commander–in–Chief: | H.R.H. Prince Frederick Charles |

| Chief of the Staff: | Lieut.-General von Voigt-Rhetz |

| 2nd Army Corps Lieut.-General von Schmidt |

|---|

|

| 2nd Army Corps Lieut.-General von Schmidt |

||

|---|---|---|

| 3rd Division | Lieut.-General von Werder | |

| 5th Brigade | Major-General von | |

| 6th Brigade | Major-General von Winterfeld | |

Divisional troops:

|

||

| 4th Division | Lieut.-General von Herwath | |

| 7th Brigade | Major-General von Schlabrendorf | |

| 8th Brigade | Major-General von Hanneken | |

Divisional troops:

Corps troops:

|

||

| 3rd Army Corps No commander |

|

|---|---|

| 5th Division | Lieut.-General von Tümpling |

| 9th Brigade | Major-General von Schimmelmann |

| 10th Brigade | Major-General von Kamienski |

| Divisional troops- | 1stBrandenburg Uhlans, No. 3 3rd Battalion Pioneers Four batteries |

| 6th Division | Lieut.-General von Manstein |

| 11th Brigade | Major-General von Gersdorf |

| 12th Brigade | Major-General von Kotze |

| Divisional troops- | Brandenburg Dragoons, No. 2 3rd Jäger Battalion Four Batteries |

| 4th Army Corps No commander |

|

|---|---|

| 7th Division | Lieut.-General von Fransecky |

| 13th Brigade | Major-General von Schwarzhoff |

| 14th Brigade | Major-General von Gordon |

| Divisional troops- | 4th Pioneer Battalion Thuringian Uhlans, No.6 Four Batteries |

| Army Troops | |

| Cavalry Corps, 1st Army | H.R.H. Prince Albredht |

| 1st Cavalry Division | Major-General von Alvensleben |

| 1st Heavy Brigade | Major-General H.R.H. Prince Albrecht |

| 2nd Heavy Brigade | Major-General von Pfuel |

| 1st Light Brigade | Major-General von Rheinbaben |

| Divisional troops | Two horse batteries |

| 2nd Cavalry Division | Major-General Hann von Weyhern |

| 2nd Light Brigade | Major-General Duke William of Mecklenburg-Schwerin |

| 3rd Light Brigade | Major-General Count Groeben |

| 3rd Heavy Brigade | Major- General von der Golz |

| Divisional troops | Two horse batteriesCorps troops- One horse battery Reserve Artillery, 1st Army Sixteen batteries |

| 2nd Army | |

|---|---|

| Commander-in-Chief: | H.R.H. The Crown Prince of Prussia |

| Chief of Staff: | Major-General von Blumenthal |

| 1st Army Corps General von Bonin |

|

|---|---|

| 1st Division | Lieut.-General von Grossman |

| 1st Brigade | Major-General von Pape |

| 2nd Brigade | Major-General von Barnekow |

| Divisional troops | Lithuanian Dragoons, No 1 1st Jäger Battalion |

| 2nd Division | Lieut.- General von Clausewitz |

| 3rd Brigade | Major-General von Malotki |

| 4th Brigade | Major-General von Buddenbrock |

| Divisional troops | 1st Royal Hussars, No 1 1st Pioneer Battalion Four batteries |

| Corps troops- | Reserve Brigade of Cavalry (including One horse battery) Colonel von Bredow Reserve Artillery Seven batteries |

| 5th Army Corps General von Steinmetz |

|

|---|---|

| 9th Division | Major-General von Ollech |

| 17th Brigade | Major-General von Horn |

| Divisional troops | 1st Silesian Dragoons, No 4 Four batteries |

| 10th Division | Major-General von Kirchbach |

| 19th Brigade | Major-General von Tiedemann |

| 20th Brigade | Major-General Wittich |

| Divisional troops | West Prussian Uhlans, No1 5th Pioneer Battalion Four batteries |

| Corps troops | Reserve Artillery Seven batteries |

| 6th Army Corps General von Mutius |

|

|---|---|

| 11th Division | Lieut.-General von Zastow |

| 21st Brigade | Major-General von Hannenfeld |

| 22nd Brigade | Major-General von Hoffmann |

| Divisional troops | Silesian Pioneer Battalion 2nd Silesian Dragoons, No 8 Three batteries |

| 12th Division | Lieut.-General von Prondzinski |

| Composite Brigade | Major-General von Kranach |

| Divisional troops | 2nd Silesian Hussars, No 6 6th Jäger Battalion Two batteries |

| Corps troops | 1st Silesian Hussars Reserve Artillery Five batteries |

| Guard Corps Prince August of Würtemberg |

|

|---|---|

| 1st Guard Division | Lieut.-General Hiller von Gärtringen |

| 1st Brigade | Colonel von Obernitz |

| 2nd Brigade | Major-General von Alvensleben |

| Divisional troops | Hussars of the Guard Jägers of the Guard Four batteries |

| 2nd Guard Division | Lieut.-General von Plonski |

| 3rd Brigade | Major-General von Budritski |

| 4th Brigade | Major-General von Loen |

| Divisional troops | 3rd Uhlans of the Guard Sharpshooter Battalion of the Guard Four batteries |

| Corps | |

| Cuirassier Brigade | Major-General von |

| Light Brigade | Major-General von Witzleben |

| Landwehr Brigade | Major-General von Frankenberg |

| The Army of the Elbe | |

|---|---|

| Commander –in –Chief: | General Herwath von Bittenfeld |

| Chief of the Staff: | Colonel von Schlotheim |

| 14th Division | Lieut.-General Count Münster |

| 27th Brigade | Major –General von Schwarzkoppen |

| 28th Brigade | Major-General von Hiller |

| Divisional troops | Westphalian Dragoons, No. 7 7th Jäger Battalion Two companies 7th Pioneer Battalion Four batteries |

| 15th Division | Lieut.-General von Canstein |

| 29th Brigade | Major-General von Strükradt |

| 30th Brigade | Major-General von Glasenapp |

| Divisional troops | Royal Hussars, No. 78th Pioneer Battalion Four batteries |

| 16th Division | Lieut.-General von Etzel |

| 31st Brigade | Major-General von Schöler |

| Fusilier Brigade | Colonel Wegerer |

| Divisional troops | 8th Jäger Battalion Two batteries |

| Army troops | |

| 14th Cavalry Brigade | Major-General Count Goltz |

| Reserve Cavalry Brigade | Major-General von Kotze |

| Pomeranian Landwehr Reiter Regiment | |

| One horse battery | |

| Reserve Artillery 7th Corps | |

| Six batteries | |

| Reserve Artillery 8th Corps | |

| Seven batteries | |

Order of Battle of the Austrian Army of Bohemia.

| General-in-Chief: | Feldzeugmeister Ritter von Benedek |

|---|---|

| Chief of the Staff: | Lieut.-Field Marshal von Hrnikstein |

| Director of Artillery: | Lieut.-Field Marshal Archduke William |

| Director of Engineers: | Colonel von Pidoll |

| 1st Army Corps General of Cavalry, Count Clam Gallas |

|

|---|---|

| Commandant of Brigade | Major-General Poschacher |

| “ “ | Colonel Count Leiningen |

| “ “ | Major-General Piret |

| “ “ | Major-General Ringelsheim |

| Brigade troops with each brigade: | One squadron Nikolaus Hussars One 4-pdr. Field batteryCorps troops Two 4-pdr. field batteries Two 8-pdr. Field batteries Two horse-artillery batteries One rocket battery |

| 2nd Army Corps Lieut.-Field Marshal Count Thun-Hohenstadt |

|

|---|---|

| Commandant of Brigade | Colonel Thom |

| “ “ | Major-General Henriquez |

| “ “ | Major-General von Saffran |

| “ “ | Major-General Duke Wurtemberg |

| Brigade troops with each brigade | One squadron Imperial Uhlans One 4-pdr. field batteryCorps troops- Two 4-pdr. field batteries Two 8-pdr. field batteries Two horse-artillery field batteries One rocket battery |

| 3rd ArmyCorps Lieut.-Field-Marshal Archduke Ernst |

|

|---|---|

| Commandant of Brigade | Major-General Kalik (Brigade attached to 1st Army Corps) |

| “ “ | Major-General Appiano |

| “ “ | Colonel Benedek |

| “ “ | Colonel Kirschberg |

| Brigade troops with each brigade | One squadron Count Mensdorf Uhlans One 4-pdr. field battery Corps troops- Two 4-pdr. field batteries Two 8-pdr. field batteries Two horse-artillery batteries One rocket battery |

| 4th Army Corps Lieut.-Field-Marshal Count Festetics |

|

|---|---|

| Commandant of Brigade | Major-General von Brandenstein |

| “ “ | Colonel Fleishhacker |

| “ “ | Colonel Poeckh |

| “ “ | Major-General Archduke Joseph |

| Brigade troops with each brigade | One squadron 7th Hussars One 4-pdr. field battery |

| Corps troops | Two 4-pdr. field batteries Two 8-pdr field batteries Two horse-artillery batteries One rocket battery |

| 6th Army Corps | Lieut.-Field-Marshal Baron Ramming |

| Commandant of Brigade | Colonel von Waldstätten |

| “ “ | Colonel Hertwegh |

| “ “ | Major-General Rosenweig |

| “ “ | Colonel Jonak |

| Brigade troops with each brigade | One squadron 10th Uhlans One 4-pdr. Field battery Corps troops- One 4-pdr. Field battery Two 8-pdr. Field batteries Two horse-artillery batteries One rocket battery |

| 8th Army Corps Archduke Leopold |

|

|---|---|

| Commandant of Brigade | Colonel Fragnern |

| “ “ | Major-General von Kreyssern |

| “ “ | Colonel Count Rothkirch |

| “ “ | Colonel von Roth |

| Brigade troops with each brigade | One squadron Archduke Charles Uhlans One 4-pdr. field battery Corps troops- One 4-pdr. field battery Eight 8-pdr. batteries Two horse-artillery batteries One rocket battery |

| 10th Army Corps Lieut.-Field-Marshal von Gablenz |

|

|---|---|

| Commandant of Brigade | Colonel Mondel |

| “ “ | Colonel Grivicics |

| “ “ | Major-General von Knebel |

| “ “ | Major-General Wimpffen |

| Brigade troops with each brigade | One squadron 1st Uhlans One 4-pdr. field battery Corps troops- One 4-pdr. field battery Two 8-pdr. field batteries One horse-artillery battery One rocket battery |

| 1st Light Cavalry Division Major-General Baron Edelsheim |

|

|---|---|

| (One horse-artillery battery was attached to each cavalry brigade) | |

| Commandant of Brigade | Colonel Appel |

| “ “ | Colonel Wallis |

| “ “ | Colonel Fratricevics |

| 2nd Light Cavalry Division Major-General Prince Thurn und Taxis |

|

|---|---|

| Commandant of Brigade | Colonel Count Bellegarde |

| “ “ | Major-General Westphalen |

| 1st Reserve Division of Cavalry Lieut.-Field-Marshal Prince Schleswig-Holstein |

|

|---|---|

| Commandant of Brigade | Major-General Prince Solms |

| “ “ | Major-General Schindlöcker |

| 2nd Reserve Division of Cavalry Major-General von Zaitsek |

|

|---|---|

| Commandant of Brigade | Major-General Boxberg |

| “ “ | Colonel Count Soltyk |

| 3rd Reserve Cavalry Division Major-General Count Coudenhove |

|

|---|---|

| Commandant of Brigade | Major-General Prince Windischgrätz |

| “ “ | Major-General von Mengen |

| Reserve Artillery of the Army:- | Sixteen batteries |

|---|

Order of Battle of the Saxon Army Corps.

| Commander-in-Chief: | H.R.H. Crown Prince Albert of Saxony |

|---|---|

| Chief of the Staff: | Major-General von Fabrice |

| Artillery Commander: | Major-General Schmalz |

| 1st Infantry Division Lieut.-General von Schimpff |

|

|---|---|

| 2nd Brigade 3rd Brigade |

Major-General von Carlowitz Colonel von Hake |

| Divisional troops | Two squadrons of 2nd and 3rd Reiter Regiments One 12-pdr. battery One 6-pdr. Battery |

| 2nd Infantry Division Lieut.-General von Stieglitz |

|

|---|---|

| 1st Brigade 2nd Brigade |

Colonel von Boxberg |

| Divisional troops | Two squadrons Guard and 1st Reiter Regiments One 12-pdr. battery One 6-pdr. Battery |

| Cavalry Division Lieut.-General von Fritsch |

|

|---|---|

| 1st Brigade | Lieut.-General Prince George of Saxony |

| 2nd Brigade | Major-General von Biedermann |

| One 12-pdr. horse artillery battery | Corps troops- Three 12-pdr. batteries Two 6-pdr. batteries Two companies of Pioneers One pontoon detachment |

Complete lists of all regiments for the Prussian, Austrian and Saxon Armies can be obtained by contacting this site.

Photographs

| Austrian Uhlan uniforms. | Austrian Hussar uniforms. |

Austrian Officer uniform.

| Austrian infantry uniform. | Austrian General Officer uniforms. |

| Austrian Intendant uniforms. | The Austrian Lorenz Rifled Musket (far left). | Austrian infantry side drum. |

Saxon cavalry uniforms.

References

| ↑1 | The Danish War of 1864 had seen the Prussians on campaign with their breech-loading rifles, but no real understanding of its full potential was realized, both by the Austrians, or the various military observers who accompanied them on campaign. |

|---|

I had always thought that Benedek was a horrible tactician,now I understand why he did what he did.

Thank you for visiting the site Nodeo-Franvier.

I think that that poor old Benedek knew only too well his own limitations. He declined the command but was told that he must “do-or-die” by The Emperor ( who had blundered the overall command at Solferino!), thus he fell on his sword, burnt all his papers and remained, in the end, dedicated to the faults of Franz Joseph.

Graham, Thank you for that information , my great grandfather was also in the War, he also fought in the Franco-Prussian War 1870-1871 do you have any I can find out details of his War History

Thank You

Hello Anne, thank you for visiting the site!

Go to the Home Page on this site and look on the right hand side. There is a column with “Friends of this site,” press the small buttons at the bottom and each museum will be displayed. The one you want is the War of 1870-1871 . The museum is situated on the battlefield of Gravelotte/ St Privat. They have a great deal of information dealing with the war and are very helpful.

Hope this will be of assistance?

Regards,

Graham J.Morris

How can I get a list of names of the soldiers who fought in the war? I think my great-great grandfather was in the war. Thanks for any assistance.

Karen,

Your best chance of obtaining information regarding individual soldiers who fought in the war of 1866 is to send an email to the museum on the battlefield of Koniggratz. They will either be able to assist you direct and/or put you in touch with other museums who have archive material that deal with the various regiments.

What side did your relation fight on, Austrian or Prussian?

Best Regards,

Graham