11th July 1708

Introduction

It is a very sad fact that many anniversaries of famous battles pass almost unnoticed by the general public. This could be due to how history is now taught in schools, at least in England, which seem to concentrate more on the twentieth century to the detriment of all else, in particular by not explaining how or why various circumstances that have helped to shape modern society came about by what may have occurred several hundred years before. Just knowing that during the Great War of 1914-1918 Germany, England, France, Russia, Austria and America, together with many other minor nations, fought each other because imperial greed had set them on the road to mass destruction is not enough. Just how these countries came into being, plus their relationship with neighbouring states is of the utmost importance in determining what made them choose peace or war. The animosity that existed between states, as well as nationalistic expectations, coupled at times with religious intolerance are all factors that need to be taken into consideration when trying to construct a valid historical overview. Therefore to allow old wars and battles, like old soldiers, to simply fade away will not only diminish our knowledge of the past, but will also, sadly, diminish us all.

Hope and Failure, 1707.

Great things had been expected after Marlborough’s resounding victory at Ramillies (23rd May 1706), and the subsequent surrender of Ath (2nd October 1706). In Italy Prince Eugene had trounced the French army under Marshal Marsin and the Duc d’Orléans, which caused them to abandon the siege of Turin (1st September 1706). While on the Upper Rhine Marshal Villars was forced onto the defensive owing to his army being whittled away by having many of his troops withdrawn to bolster the battered French army in Flanders. Spain alone remained still tenable to Louis XIV, with no decisive Allied progress being made. Only the growing fear of Swedish involvement in Northern Germany caused the Allies some anxiety. Thus the forthcoming campaign of 1707 seemed set to see the hopes of the Sun King dashed, and the French finally brought to the peace table. [1]Chandler. David, Marlborough as Military Commander, page 183

Unfortunately things started to deteriorate rapidly during the late spring of 1707. The Act of Union, which brought together Scotland and England in April of that year, did not go down well with the majority in Scotland, while the problems arising from internal bickering between the Allied powers soon put a damper on any constructive plans that Marlborough may have harboured for a new offensive in the Moselle valley. The Dutch once more found strong objections to any plan that would take their troops away from Flanders, while the Austrians had given the war- worn Louis XIV a fresh injection of manpower by signing a convention with his forces in Northern Italy, which allowed for the unconditional repatriation of some 20,000 French prisoners of war. Not content with this, the Austrian Emperor (Joseph I) began to concoct his own military plans for an expedition against Naples, a plan that required the assistance of the Anglo-Dutch fleet as well as 5,000 of their soldiers.[2]Ibid, page 185

In Spain a plan was proposed for a march on Madrid by the combined Allied forces under Galway and Stanhope, amounting to almost thirty thousand men, but king Charles III (Archduke Karl of Austria, pretender to the Spanish throne, who became Holy Roman Emperor in 1711) considered that the troops would do better being placed in garrisons protecting the provinces of Catalonia and Valencia. This vacillation led to a compromise, causing the army to be split, king Charles and Stanhope marching to garrison Aragon and Catalonia, while Galway moved on Madrid. Here Marshal Berwick (illegitimate son of James, Duke of York, later king James II of England- and Marlborough’s nephew) covered the approaches, with his magazines in Murcia well stocked, and several thousand fresh troops on their way to join him from Italy.[3]Churchill. Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Time, Vol II, page 230

With fifteen thousand troops, to Berwick’s twenty five thousand, Galway was quite seriously outnumbered. Unable to ascertain the strength of the French forces before him Galway pressed on eager to give battle, which was joined on April 25th before the walls of Almanza, in the province of Castilla y Leon. Here the allies were decisively beaten, losing over half their number in killed, wounded and prisoners. As Marlborough himself stated, “ This ill success in Spain has flung everything backwards, so that the best resolution we can take is to let the French see we are resolved to keep on the war, so that we can have a good peace.[4]Churchill. Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 230-236

The Duke himself took the field in May 1707, joining his army, which numbered some ninety thousand, and was concentrated near Brussels, for a march south towards Hal, but since the Dutch had issued strict instructions to their field deputies to avoid giving battle at all costs, Marlborough was forced to retire somewhat ignominiously back towards Brussels, while Marshal Vendôme manoeuvred with the French field army to tempt him into a false position uncovering Brussels and Louvain. Back once again around his old campaigning ground along the Dyle River, east of Brussels, Marlborough received yet more bad news. The French Marshal Villars had captured the lines of Stollhofen on the Upper Rhine. This massive system of trenches, redoubts and fortifications were some of the strongest constructed during the War of Spanish Succession, and prevented any incursion into Germany along the Rhine valley. The problem was that the defenders of these seemingly impregnable works were the poor remnants of the Austrian Emperor’s Rhine army, which had been sadly depleted by its master to bolster his grand ideas in Italy. Thus, on 23rd May 1707 Marshal Villars, almost without any loss of life, occupied the Stollhofen position and Germany was laid wide open.

As if all the above were not bad enough, yet another misfortune was about to fall upon the Allied cause. The joint sea and land operations against Toulon began well, with Prince Eugene marching from Italy to attack the port from land, while Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell sailed with the British fleet to bottle up the French ships in the harbour. However Eugene had grave reservations about the whole affair, and what should have been a great opportunity for delivering a decisive blow at the soft underbelly of France became no more than a costly raid. As Sir Winston Churchill explains, ‘ Properly speaking, it was no siege, but only an attack by the fleet and one by the field army upon the fortified position of another. Eugene, whose sentiments are only too apparent, bent to his task against his mood and judgment in fulfilment of his promise to Marlborough “that he would do his best.” Besides this, however, he formed a certain contract, comprehensible to fighting chiefs, with Shovell and the English admirals. No soldier of high quality can be unmoved by the ardour and comradeship of the naval service in a joint operation. Eugene was evidently affected by Shovell’s grit, resource, and zeal. “ In spite of the representations I have made to the Admiral,” he wrote to the Emperor (August 5th), “ he absolutely insists upon carrying on with the enterprise of Toulon…If they wish to proceed to its serious undertaking, in spite of all the difficulties they see with their own eyes, the troops of Your Imperial Majesty will certainly not separate from them.” And later, “ Although the Admirals do not understand the land service, they refuse to listen to facts, and adhere obstinately to their opinion that for good or ill, everything must be staked on the siege of Toulon. Yet the pure impossibility of this is clearly before their eyes.”

‘ No one, on the other hand, must ignore the estimate of the difficulties presented on the spot by so sincere and noble a warrior as Eugene. He may well have been right that the task was impossible. It does not look in retrospect so hard as many of the feats of arms which he performed both before and after. But it failed, and with it failed the best hope of redeeming for the Allies the year 1707.’ [5]Churchill. Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 254-258

For his part Marlborough now tried to make something out of nothing. Knowing that the French had sent troops from both Spain and Flanders to bolster the forces defending Toulon, the Duke endeavoured to manoeuvre the French away from their foraging area around Gembloux. Still with strict instructions from the Dutch not to offer battle, which was being reciprocated by the French who also feared bringing on a general engagement in Flanders now that their army there had been weakened, the Allied army moved out of its camp on August 10th, marching towards Genappe in an attempt to turn the French left flank. Marshal Louis-Joseph, Duc de Vendôme, one of the finest commanders in the French army, despite his appalling habits and fiery temper, soon fathomed Marlborough’s plan and retired back towards Seneffe, with the Allies floundering around in torrential rain in his wake. The result of these manoeuvres resulted in both the French and Allied armies occupying roughly the same positions they started from in May. With Vendôme unlikely to make any move that would jeopardise his lines of communication, and Marlborough constricted both by the orders of the Dutch Deputies and the terrible state of the roads, the campaign of 1707 petered out, ‘…The recovery of France seemed complete in every theatre. Grievous defeats had overtaken all the allied arms at Almanza and Stollhofen; cruel disappointment at Toulon. His (Marlborough’s) own campaign had been fettered and ineffectual. The Empire pursued its own woebegone, particularist ambitions. Southern Germany had allowed itself to be ravaged without any rally of the Teutonic princes. The Dutch, angry and disappointed, hugged their Barrier, and their grasping administration had already cost the Allies every scrap of Belgian sympathy…In this adversity the Confederate armies sought their winter quarters; and Marlborough returned home to face a Cabinet crisis, the Parliamentary storm, and, worst of all, bedchamber intrigue.’[6]. Churchill. Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 275-276

Boldness and Good Luck.

And so the New Year of 1708 brought fresh hope to the French monarch. The clouds of misfortune and doubt, which had hovered over the Bourbon throne, had cleared away, and once more the “Sun King’s” radiance shone forth.

The Act of Union with Scotland had caused widespread disaffection among the Scots, and now Louis XIV turned his attention to assisting the “Pretender,” James Edward, in his bid to seize the Scottish throne. The port of Dunkirk was humming with activity, as a task force of 6,000 French troops, together with 13,000 stands of arms was made ready to accompany the prospective King James III for a landing in Scotland.

Unfortunately the weather in February 1708 turned stormy, causing a delay of almost one month, during which time the English Parliament took prompt action, sending a fleet to blockade Dunkirk, while mobilising the militias and recalling ten regiments of foot from Flanders, the latter having a miserable time cooped up on board their transport ships during the four day passage to Teignmouth, made in gale force winds and heaving swell.

On the 17th of March the French set sail from Dunkirk, the stormy weather having scattered the blockading squadron. On the 21st March they arrived at the Firth of Forth, but owing to the Allied fleet now being close on their trail, it was decided to sail on to Inverness. Here the whole scheme was abandoned, as there had been little sign of enthusiasm from the Scots, and the French troops were suffering terribly from being crammed together on the wind swept decks. The French lost over two thousand men due to seasickness and the elements, also one ship was captured; ironically she was an English vessel that the French had taken in 1703. All of this did not worry the French king unduly, he had always considered the Scottish venture a hazardous undertaking, and was quite content to have what remained of his expeditionary force back in France.

Now that the crisis had passed, the ten British regiments returned to Flanders, while Marlborough set sail for The Hague on 12th April to attend an Allied conference to discuss their plans for the forthcoming campaign. Here it was decided that all the available troops in Germany and the Netherlands should be grouped into three armies. In Flanders, under the Duke’s personal control, the main army consisted of 100 battalions and 150 squadrons; the second, commanded by Prince Eugene, complimented by a detachment from Flanders, and made up of troops from Baden-Baden, the Palatine, Würzburg and an Imperial contingent, around 45 battalions and 60 squadrons, forming on the Moselle River. The third army, under George Lewis, Elector of Hanover (the future king George I of England); 37 battalions and 47 squadrons, to operate on the Upper Rhine.[7]Chandler. David, Marlborough as Military Commander, page 205-206 As well as these arrangements the Allied forces in Spain and Italy were instructed to adopt a defensive attitude.

The French, even allowing for the crippling cost of the war on the economy, still managed to put together five field armies. The main effort was to be directed against Flanders and on the Rhine. The Duke of Berwick and the Elector of Bavaria (Max Emmanuel) taking charge of the Rhine army, with Marshal Villars being sent to Dauphiné. The grandson of Louis XIV, the Duke of Burgundy, was instructed to join Marshal Vendôme, with whom he would share command of the army in Flanders, a decision that was to have grave consequences in the future. In Spain the Duc d’Orléans and Marshal Bezon would work in coordination with Marshal Anne-Jules Noailles’s army of Catalonia in an attempt to take back the eastern seaboard, while The Army of Dauphiné would go onto the defensive. For the coming campaign in Flanders the French were mustering 131 battalions of infantry and 216 squadrons of cavalry, while their Rhine army stood at around 79 battalions and 138 squadrons.[8]Chandler. David, Marlborough as Military Commander, page 206

On the Allied side Marlborough still harboured the idea of a “descent” on the French coast as part of his overall stratagem for the new campaign. Thus General Thomas Erle was ordered to gather 11 battalions of British infantry on the Isle of White in preparation for a landing on either the French or Belgian coast as Marlborough saw fit. The Duke himself travelled to Hanover during the third week of April in order to allay the fears of the Elector who had become perturbed concerning his own role in the forthcoming campaign. Therefore, to appease the suspicious George Lewis, Marlborough was forced to bolster the Elector’s forces with 2000 cavalry taken from Prince Eugene’s Moselle army. The latter had been in secret contact with Marlborough and they had agreed on a plan whereby Eugene would march his army to Flanders to join Marlborough’s.

War weariness was affecting the Dutch, and the Flemish population in Flanders were heartily sick and tired of Dutch incompetence and vacillation. Thus the time seemed appropriate for the French to take the initiative, and Vendôme had received permission from the King to risk giving battle under favourable circumstances. Therefore the vexatious marshal planed to besiege the town of Huy, this would draw the Allies away from French Flanders and battle could be sought on ground favourable to the powerful French cavalry. However a serious situation now arose which was to have a major effect on the forthcoming campaign. The King’s grandson, the Duke of Burgundy, had been dispatched to share command of the army with Vendôme. This was to cause much friction between the two commanders, and dire results at the battle of Oudenarde.

Considering himself able to handle military matters as he saw fit, the 26-year-old Burgundy put forward his own plan for a direct advance on Brussels, thereby seeking to win over the disenchanted population. Although Vendôme was not in favour of the plan he nevertheless, reluctantly agreed, and the French army of over one hundred thousand men began massing around Mons. On the 26th May they had crossed the River Haine and went into camp at Soignies. To meet this threat Marlborough, with some ninety thousand men, moved towards Hal, which caused the French to move over the River Senne in the direction of Braine I’Alleud, threatening Louvain. To this Marlborough quickly proceeded, on the 2nd June, to march back through Brussels to his old camp at Tarbanck, covering Louvain. Fully aware that Prince Eugene was not yet ready to commence his march on Flanders, Marlborough thought it prudent to protect Brussels. [9]Chandler. David, Marlborough as Military Commander, page 209

There now followed a month of frustration for both sides. For the French, Prince Eugene’s arrival at Coblenz had caused concern as to what possible action he may be thinking of undertaking, while Marshal Vendôme still argued for laying siege to Huy. King Louis accepted Vendôme’s suggestion, but once again Burgundy put a damper on things and on 11th June orders from Versailles came suspending any action against Huy until Prince Eugene’s intentions on the Moselle had been fathomed. For his part Eugene only became ready to commence his march to join Marlborough on 29th June, and this with only a fraction of the force originally intended to be at his disposal, the Elector of Hanover commandeering 25,000 of the original 40,000 troops under Eugene command. Not only this, but three days after setting out for the Spanish Netherlands, Eugene had the talented Duke of Berwick, with 27,000 men giving chase. Nevertheless, if Eugene showed his usual flair and energy, there might still be a chance to join up with Marlborough and administer a crushing blow to Vendôme before Berwick had a chance to assist.[10] The whole month of June had been one of worrying frustration for Marlborough, who spent most of his time inspecting the troops and writing letters.

Meanwhile the unkempt and snuff covered Marshal Vendôme had been planning his next move. Working in conjunction with the French Minister of War, Count Bergeyck, both of whom were fully aware of the disillusionment of the population of the Spanish Netherlands, Vendôme sprang into action on the 4th July, marching west and crossing the Senne River, then moving rapidly for the River Dender at Grammont. Out in front of the French main army, two flying columns, commanded by Generals Chemerault and La Motte forged ahead to secure the important towns of Bruges and Ghent, where the townsfolk welcomed the French as liberators. Thus at the cost of boot leather Marlborough’s communications with England were severed, and his supply lines to Antwerp and Holland seriously jeopardised. Unfortunately these resounding operations were undermined by the animosity that existed between Vendôme and Burgundy regarding the next stage of the campaign. Although having been advised by king Louis to take heed of what the much experienced French Marshal had to say, Burgundy still thought himself best able to judge the military situation, and both commanders, together with their respective staffs, adopted the childish attitude of speaking to one another as little as possible. [10]Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 132-133

At 10 o’clock on the night of the 4th July, Marlborough, receiving the news that the French were on the move, ordered the army to strike camp and, at 2 a.m. on the morning of the 5th July, they were marching towards Brussels. In the early afternoon, when near the city, the Duke penned the following letter:

Having had advice last night that the enemy were decamped and that they had made a strong detachment some hours before under the command of M. Grimaldi, we have been upon our march since two o’clock in the morning, and, having noticed at noon that the detachment was advancing as far as Alost, and had broken down the bridges over the Dender, I immediately detached two thousand horse and dragoons under the command of Major General Bothmar, to pass at Dendermonde to observe them and protect the Pays de Waes. By what we learn hitherto their army is advancing as far as Ninove, and we shall continue our march according to their further motions.[11]Dispatches, vi, page 95. Quoted in, Churchill. Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 344

Unfortunately this proved to be one of those rare occasions when Marlborough’s judgement failed him. The Allied army were slowed by torrential rain, the Duke himself lost his way whilst on reconnaissance, also the news that the French had managed to occupy Ghent and Bruges caused general despondency among all ranks.[12]Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 134 The air of gloom seems to have affected Marlborough greatly, and this, coupled with his general fatigued state caused him to become halfhearted and lethargic, and as the Prussian commissary at British headquarters, Brigadier Grumbkow wrote to his king, Frederick I:

The blow which the enemy dealt us not merely destroyed all our plans, but was sufficient to do irreparable harm to the reputation and previous good fortune of My lord Duke, and he felt this misfortune so keenly that I believe he would succumb to his grief early the day before yesterday, as he was so seized by it that he was afraid of being suffocated.[13]Quoted in, Churchill, Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 349 * Churchill and Falkner give 8th July as the date of Eugene’s arrival at Marlborough’s HQ, while Chandler … Continue reading

Fortunately Prince Eugene, having ridden on ahead of his cavalry, arrived (Sunday 8th July)* at Marlborough’s headquarters, which were now at Assche, west of Brussels. With the arrival of his friend and fellow campaigner, the Duke’s spirits lifted, and he shook off his cloak of gloom, becoming once again the firm and resolved commander. Fully realising that the French had the advantage, the Duke now gave orders for Brigadier Chandos to reinforce Oudenarde with 700 men, while the Earl of Cadogan with a strong advance guard, followed by the main army, was to advance rapidly on Lessines to gain control of the vital crossing on the Dender River.

As noted above, the antagonism that existed between the French commanders caused both men to put forward their own plans for the continuation of the campaign. Vendôme had been all for going straight at the town of Oudenerade with a strong force of all arms, while the main French army held the line of the Dender River to oppose any moves made by the Allies. This plan was not to Burgundy’s liking, he preferring to cover northern France and their supply depots at Tournai and Lille. He therefore considered that to lay siege to the town of Menin was the better option, one that Vendôme thought far too tame; the Marshal did not wish to concede territory back to Marlborough unless forced to do so. Not being able to agree on which course of action to take, the matter was referred back to Versailles for the king’s decision. While awaiting a reply, Vendôme began to prepare the army for a move covering the Dender, while at the same time investing the town of Oudenarde.[14]Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 135. These troops consisted of several thousand cavalry. This point is worth remembering during the battle.

Moving rapidly, Cadogan had reached Lessines with the Allied advance guard well before dawn on the 10th July, and realising that they had lost the option of securing the Dender River line, the French army (Burgundy’s orders again) moved north to Gavre, with the intent of placing itself between the Allies and the River Scheldt, the troops covering Oudenarde* were also pulled back to the main body, all of this to the annoyance of Vendôme who was keen to give battle.[15]Chandler. David, Marlborough As Military Commander, page 214

For the French it seemed that they had ample opportunity to scupper any Allied manoeuvres by occupying a central position, ‘…They held the cord, while the allies to forestall them must move around an arc three times as long. It was therefore with complacency that they lay on the night of the 10th (July) within a few miles of the Scheldt, over which their bridges were a-building. Even if Marlborough’s advance troops were holding Lessines, they had plenty of time to blockade the bridgehead of Oudenarde from the west and thus put themselves behind a secure river line and within two marches of Lille.’[16]Churchill. Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 355

With Lessines secured Marlborough and Eugene now decided to make a rapid move on Oudenarde in order to cross the Scheldt before the French had completed their own bridging operations. Of paramount importance was the construction of pontoons over the river to facilitate the crossing of the army. Therefore at 1 a.m. on the morning of July 11th Cadogan was once again sent with 16 battalions and 8 squadrons, plus the bridging train and 32 light artillery pieces to secure a crossing at Oudenarde. He also had orders to repair and improve the roads. Coming in sight of the river at 9 a.m., Cadogan informed the Duke that the French were still at Gavre. By noon the first of his British battalions were across the Scheldt, and the rest of the pontoons placed in position soon after. The French themselves, showing no particular need for haste, began crossing a Gavre around 10 a.m.[17]Chandler. David, Marlborough As Military Commander, page 214

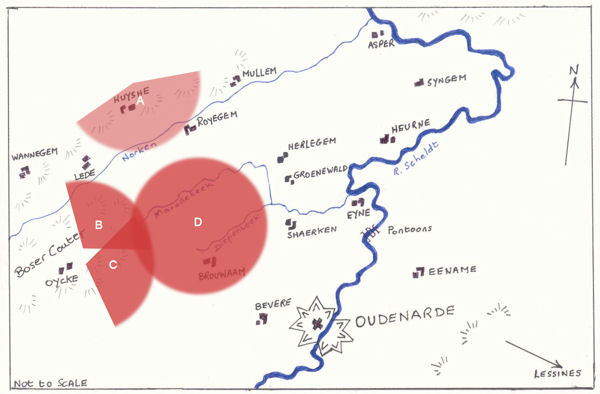

At around the same hour Marlborough received Cadogan’s message and, together with Prince Eugene, he set off towards the river accompanied by General Natzmer with twenty squadrons of Prussian cavalry, ordering the rest of the army to follow as rapidly as possible. At 1.00 p.m. the Duke was clattering over one of the pontoons seeking to reconnoitre the village of Eyne, while, leaving 4 battalions to guard the bridges, the other 12 battalions of Cadogan’s command moved towards the River Diepenbeck, covered on his left flank by General Rantzau’s 8 squadrons.

The Battle.

Rantzau’s Hanoverian troopers soon came up against the French advance guard under General Duc de Biron, who commanded a mixed force of 20 squadrons and 7 battalions of Swiss, and was marching on the village of Heurne. Taken aback by the presense of Allied cavalry already on the same side of the river as himself, Biron’s 20 squadrons soon checked Rantzau’s advance, and then Biron himself dismounted and climbed the church tower of Eyne in order to assess the situation. Instead of just a few Allied squadrons that he thought may have been sent on ahead on a reconnaissance mission, Biron was shocked and alarmed at the sight that met his gaze. Before him lay the enemy’s pontoon bridges with battalions and squadrons already over, while pouring down the shallow hillside on the other side of the river from the direction of Eename, cloaked in clouds of dust, marched a seemingly endless column of infantry and cavalry- the whole Allied army was heading in his direction. Acting with promptness, Biron sent messengers galloping back to inform Vendôme and Burgundy of the situation. Upon receiving Biron’s report Vendôme was flabbergasted, stating: ‘If they are there, then the devil must have carried them. Such marching is impossible.’[18]Churchill, Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 360 However Vendôme was no slouch, although he still only considered the Allied movement as a ploy, he immediately sent back orders to Biron telling him to attack at once, while the Marshal himself brought forward troops in support.

Just when Vendôme realised that he actually had the whole Allied army to deal with has been a matter of conjecture. Churchill says that the Marshal and his personal secretary, Alberoni, gave the hour as 10 a.m., and that the attack should begin at once. It was Burgundy who delayed any action until four in the afternoon, by which time Vendôme deemed it too late. Churchill goes on to say that it must have been at least 2 p.m. when Vendôme at last understood what was happening, and that his orders to Biron arrived at about 1.30 p.m., by that time Marlborough and Eugene were over the river and the Duke was already positioning a six gun battery on Cadogan’s left to the rear of the village of Schaerken.[19]Ibid, page 361 Whatever hour Vendôme’s orders reached Biron things had altered dramatically, and the French advance guard commander was seriously outnumbered.

On the Allied side more German and British battalions under the Duke of Argyll were about to cross over the pontoons, while, and at 3 p.m., Cadogan’s battalions, with bundles of fascines prepared before hand, had placed them across the Diepenbeck and began to drive back the Swiss skirmish line on their supporting battalions around Eyne. At the same time Rantzau’s Hanoverian dragoons crossed over the stream outflanking the Swiss right flank. In the meantime Vendôme had sent a message to Burgundy, instructing him to move forward with the whole of the infantry and cavalry of the French left wing to capture the Allied bridgehead. This plan was indeed the correct way to proceed. With most of the Allied army still strung out on the march, the superiority of French numbers would have had a telling effect on the small forces of Cadogan and Rantzau.

It was at this stage of the battle that a peculiar incident occurred, which, even allowing for what transpired later on, was to have a decisive impact on Vendôme’s demeanour during the fighting, and indeed on the whole outcome of the battle itself.

Just as General Biron was about to move his three reserve Swiss battalions forward from around the village of Heurne, in support of his other four battalions at Eyne, Lieutenant- General Marquis de Puységur (Vendôme’s chief-of-staff), who had ridden forward to set out the French camp, informed Biron that the ground to his front was not suitable for cavalry owing to its soft and marshy nature. At the same time Marshal Matignon, who had also ridden up, added his two pence worth of topographical knowledge concerning the unsuitability of the ground. Just where these two men obtained their information is a mystery. Considering that several thousand French cavalry had been milling around the area when Oudenarde had been invested earlier in July, one would have thought that any areas that were not suitable for mounted troops would have been noted. Also it would appear that no one seems to have collected any information from local peasants or farmers concerning the state of the ground. With Rantzau’s eight Allied squadrons massed in front of them, how did they suppose that the ground was not passable to the French yet passable for the Allies? As if this was not bad enough, when Vendôme galloped up to find out why Biron was not carrying out his orders, he was also informed by Puységur that a morass covered the area between them and the enemy. The Marshal accepted this, but with decidedly bad grace, and turned his reinforcements to the west of the Ghent road, thus abandoning Biron to his fate.[20]Churchill. Sir Winston, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 362 Just why Vendôme, or for that matter Biron himself, did not send a few mounted detachments forward to examine the ground is totally baffling. Even if there was boggy ground to Biron’s front, this would still mean that the Allies could not use their cavalry to any effect on his flank, and by swinging their massive superiority at this time in both infantry and cavalry around to the right, while bolstering Biron’s line with artillery and infantry, the French could have crushed any opposition already on their side of the river and captured the bridgehead.

While Vendôme was being persuaded that no offensive was possible on Biron’s front, Burgundy had arrived at the heights of Huyshe, to the north of the Norken River, with the main body of the French army. Although a sound position from which to offer a defensive battle, the heights of Huyshe was not the place to pause when it was evident that the Allies were approaching in strength. By throwing the whole weight of their army at the Allied bridgehead they would, to all intent and purpose, have gained the initiative, and if not crushed the Allied army as it came forward piecemeal, then at least caused it to retire somewhat ignominiously back the way it had come. It was now 2.45 p.m., and with only a few precious hours remaining before the onset of evening, poor general Biron was left very much to his own devices.[21]Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 143

Sir Winston Churchill tells us that no record exists of any orders being sent to Cadogan, and he concludes that despite this that general “acted in the very closest concert with his chief.”[22]Churchill. Sir Winston S. Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 363 To this end, at 3 p.m., as noted above, Cadogan’s 16 battalions moved forward to attack the village of Eyne.

Cadogan’s assault completely overwhelmed the Swiss battalions, who, feeling isolated, gave way without any show of their usual grit and stubbornness. Of the seven battalions under Biron’s command, three of the four posted at Eyne surrendered without a fight, while the other fell back to join their comrades who were advancing from Heurne. Here they were hit by Rantzau’s squadrons coming in on their left flank and were either killed, captured or dispersed.[23]Ibid, page 364 Rantzau’s cavalry, the future king George II amongst them, now began rampaging along the line of the Ghent road where they smashed into the compact squadrons of the Royal la Bretache Régiment, pushing them back in great disorder to the Norken river. Here, as more French cavalry now began to come forward, and being fired upon by a battery of artillery near Mullem, Rantzau pulled his troopers back in reasonably good order to join Cadogan’s battalions around Heurne village, bringing back with them ten captured standards and two kettledrums.

Cadogan’s attack and Rantzau’s cavalry charge had brought Marlborough precious time, and now at around 5 p.m., with more Allied reinforcements crossing over to bolster his battlefront, he directed Cadogan to move his infantry to the west along the Marollebeek, while General Natzemer’s 20 Prussian squadrons came forward to join Ranzau’s cavalry protecting the right flank. On Cadogan’s left, Argyle extended the line with his 20 battalions towards the village of Schaerken.

As these Allied movements were being implemented, Burgundy sent General Grimaldi, with 16 squadrons of cavalry, orders to cross over the Norken River as a prelude to a general forward movement by the French centre and right wing. Once again, and with no real sound reconnoitring of the ground, Grimaldi informed Burgundy that the area was not suitable, and without getting a second opinion on the “actual” state of the ground, which had we must not forget been passed over, in part, by Rantzau’s troopers, Burgundy agreed to allow Grimaldi to fall back to Roijgem, where the young Prince had himself set up his headquarters near a windmill. It was from here, at 4.30 p.m., that Burgundy also ordered six battalions of infantry to attack Groenewald, which was successfully repulsed by the Prussians holding the village. The sound of this engagement brought Vendôme onto the scene at the head of 12 fresh battalions, ‘…but did not see fit to pause at Roijgem mill to concert any plan of action with Burgundy. Instead he rallied the two brigades repulsed from Groenewald, led them forward again with his own force in a new series of attacks against the Allies behind the Marollebeek between Herlegem and Groenewald. Cadogan and the Prussians withstood the pressure, and Vendôme ordered up more and more infantry from the French right until 50 battalions were engaged’. [24]Chandler. David, Marlborough as Military Commander, page 218-219

Despite fighting from behind the fences and hedges surrounding Groenewald, and having been reinforced by their two battalions bought up from the pontoons, Cadogan’s Prussians were finally forced out of the village just after 5 p.m. by unrelenting French attacks. But even as they fell back the Duke of Argyll came into line with his twenty battalions of Hanoverian, Hessian and British infantry on Vendôme’s right flank, threatening him with envelopment. This proved too much for Vendôme, and throwing restraint to the wind he plunged into the thick of the fighting with a Half-pike in his hand, orderings still more battalions forward in dense masses.[25]Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 146

These massive French assaults, if properly coordinated and sustained by a concerted attack by Burgundy, who still had over 30,000 men at hand, would without doubt have overwhelmed the Allied position, but with Vendôme fighting in the ranks, and Burgundy surrounded by sycophants and armchair topographers, it is small wonder that every opportunity that presented itself to the French was squandered. As Churchill states:

We must regard the paralysis of the French left wing at this moment as most fortunate for the Allies. No one can pretend to measure what would have happened had Cadogan been driven, as he surely would have been, back upon Eyne by the concerted onslaught of overwhelming numbers. But ill-luck does not exculpate Vendôme. He should not have indulged himself by entering the local fighting around Groenewald unless he could keep a sense of proportion and a comprehensive grip of his great army. Half an hour later it was apparent that the left wing was still motionless; but by that time he was fighting with a pike, like a private soldier rather than a marshal of France and charged with the supreme control of ninety thousand men.[26]Churchill. Sir Winston. S, Marlborough: His Life and Times,Vol II, page 368

Indeed, possibly one of Vendôme’s last orders (suggestions?) to Burgundy, before he threw himself into the fray, was to advance over the Norken with the French left wing and crush Natzemer and Rantzau’s squadrons and then turn to roll up the Allied line. The fact that this was never attempted was again due to the interference of the “ground expert” Puységur, who informed Burgundy that the banks of the Norken River were too marshy to support the passage of cavalry. Once again Burgundy accepted this without endeavouring to send out any cavalry to test the ground, and once again a great opportunity was lost.

Nevertheless, at 5.30 p.m. French pressure was again beginning to tell on the Allied position as their 50 battalions slowly gained ground over Marlborough’s 36 battalions. Luck and good marching now once again turned in favour of the Allies, as General Lottum arrived on the field with 20 foot -sore but eager battalions to bolster the line. This fresh injection of manpower was immediately used to extend the line from Schaerken village along the southern bank of the Diepenbeek stream, countering in the nick of time the French advance in that area. Now, at around 6.00 p.m., Marlborough gave Prince Eugene command of the Allied right wing, while he rode to the right to take charge of the fighting along the Diepenbeek. He was also now comforted by the news that 18 Hanoverian, a Hessian and Saxon battalions were following in Lottum’s wake, and that General Lumley with his cavalry had passed through Oudenarde, however the Dutch and Danish wing of the Allied army under General Overkirk had been detained by a breakdown of one of the bridges in the town.[27]Chandler. David, Marlborough as Military Commander, page 220

As the Hanoverian, Hessian and Saxon troops arrived on the field Marlborough slotted them neatly into line with Lottum’s battalions on the left and, with the skill he had used at the battle of Ramilles in 1706, slowly pulled Lottum’s troops from the firing line, leaving their regimental standards in place to deceive the French. Once clear of the front Lottum’s soldiers formed in column of march and, after refilling their cartridge pouches moved to the right where they came into line to give support to Cadogan’s hard pressed battalions around Groenewald and Herlegem. This manoeuvre proved most fortuitous as by 6.30 p.m. both villages were held by the French and the Allied line here was beginning to crack. With the arrival of Lottum the situation was stabilised and Groenewald retaken, but only after a ferocious hand-to-hand battle in which the French gave ground slowly.[28]Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 149

At sometime during the afternoon Marlborough had received intelligence reports from his scouts that the Boser Couter Hill, which overlooked the battlefield from the west, was clear of any enemy troops. Turning to General Overkirk, who had ridden on ahead of his Dutch and Danish contingent the Duke instructed him to take his strong corps of 24 battalions and 12 squadrons and move past the village of Oycke and thence onto the Boser Couter to turn the French right flank. The Duke fully expected that this manoeuvre would be carried out at around 6.00 p.m., but due to the problems involved repairing the broken bridge in Oudenarde, and the subsequent bottleneck created by the pile up of troops, it was not until about 7.00 p.m. that Overkirk finally managed to get his forces onto the hill.[29]Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, 150

Meanwhile the French were still throwing in repeated attacks and Marlborough was forced to send an urgent message to Overkirk asking him to send help to the outnumbered Allied infantry holding the chateau of Brouwaan on the extreme left of the line. As with all of his battles Marlborough was well served by his subordinate officers. Overkirk responded immediately, detaching Major-General Week with eight Dutch battalions who moved off their original line of march towards Brouwaan. Here they burst upon the exposed French right, causing it to form a refused flank to meet the unexpected threat of envelopment.

At just after 7.00 p.m., and while Overkirk’s corps was moving towards the Boser Couter, General Lumley had received orders from the Duke to take his 17 squadrons of British cavalry from a holding position near Bevere and proceed to the right flank to bolster the line. Prince Eugene, always ready to follow orders, or use his own initiative, now reinforced by Lumley’s troopers, sent Natzemer’s Prussian squadrons in a spoiling and time gaining attack on French left flank around Herlegem.

The charge of Natzemer’s Prussians across the Ghent road shows how wrong Burgundy was to follow the advice of the “not suitable for cavalry” clan: ‘…the rapid progress of these horsemen demonstrated Puységur’s complete error in warning against an advance by French cavalry over pretty well the same ground earlier in the day.’[30]Ibid, page 151

Natzemer’s squadrons ploughed into the French line of cavalry protecting the left of Herlegem, then swinging right, routed two battalions of infantry and cut down and dispersed the crews of an artillery battery. But by now Natzemer had lost control over his troopers and the attack carried too far, coming up against the immaculate and well ordered ranks of the French Maison du Roi cavalry who had moved forward from Royegem:

Natzemer, left quite alone in the midst of the enemy, received four sabre-cuts, and escaped only by leaping a broad ditch, “full of water in which a dead horse was lying.” Survivors of the twenty squadrons found refuge behind the ranks of Cadogan’s and Lottum’s battalions. Three quarters of the gendarmes (Prussians) perished. The twenty squadrons existed no more as a fighting force; but precious time had been gained.[31]Churchill. Sir Winston. S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 135

The sacrifice of Natzemer’s squadrons had not only brought precious time for Cadogan, Lottum and Argyle, but had also diverted French attention away from the growing threat to their right flank, which was about to be fallen upon like a thunder clap.

At 8.00 p.m. Overkirk was finally in position on the Boser Couter, with the yawning void of the French right flank and rear before him. With the rest of the Allied line now redoubling their efforts to contain the struggling French masses on their front, Overkirk now sent Count Tilly with twelve squadrons of Danish cavalry thundering down on the enemy open flank, while at the same time the Prince of Orange and Count Oxenstiern led forward sixteen Dutch infantry battalions between the château of Brouwaan and the village of Schaerken.[32]Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 152

The surprise was complete, and the French fighting line began to disintegrate. Even the bold, if slightly ruffled Masion du Roi could do nothing to redress the situation on the right flank and centre, which was now almost surrounded, while over on the left Cadogan was pressing his attack from Groenewald, ‘ The straight line had become a vast horseshoe of flame within which, in a state of ever-increasing confusion, were more than fifty thousand Frenchmen. It was now half-past eight. But for the failure of the bridges in Oudenarde this situation might have been reached an hour earlier.’[33]Churchill. Sir Winston. S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 375 By 9.00 p.m., in the gathering darkness, Marlborough ordered a halt, and the rounding up of French prisoners began.

Despite the lateness of the hour Marlborough’s bold battle plan, albeit with the aid of the incompetence shown by the French high command, had been successfully completed. From his viewpoint at the Royegem mill, Burgundy had seen the Danish and Dutch pressing forward in his direction and thereupon decided it was prudent to leave the field, and amid much clattering of plate and clinking of bottles, the servants packed away the food and wine which had been spread around the royal headquarters; while Burgundy and his cronies made haste to put distance between themselves and the victorious Allies.

Vendôme, covered in sweat and dirt, his face blackened with powder, had managed to extricate himself from the general chaos, and caught up with Burgundy and his entourage at around 10.00 p.m., as they were making their way back on the Ghent road. The gruff old Marshal, furious with the whole conduct of the battle, demanded to know what was to be done to try and redress the situation. Burgundy began to explain, or attempt to explain, his actions, but Vendôme cut him short, “Your Royal Highness must remember that you only came to this army upon condition that you obeyed me,” and he went on to say that he failed to understand how the young Duke had managed to remain inactive with 30,000 fresh troops, while the rest of the French army had been fighting for their lives under his very nose. Whether through arrogance or ignorance, Burgundy allowed the Marshal’s comments to pass, and soon Vendôme cooled down. He now proposed to renew the struggle the next day, using the intact French Left wing, and what elements of the rest of the army he could pull together. However, Burgundy remained adamant that the French were short of ammunition, and in no fit condition to become embroiled in another major battle. Once again Puységur and Matignon concurred with this view, and this time they were in all probability correct, when one considers the state of the morale of men who have been engaged in a defeat and witnessed one. Realising that he had no chance of persuading any of the other high command to support his views, Vendôme reluctantly ordered the retreat to continue, and turning to Burgundy he snarled: ‘And you, Monsieur, have long had that wish.’[34]Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days page 154

The battle had cost the French some 5,500 in killed and wounded, and another 9,000 prisoners, which included 800 officers, together with 106 regimental colours and standards. Ten pairs of kettledrums and over 4,000 horses and mules were also taken. The Allied losses amounted to 2,972 killed and wounded.

The French army never recovered during the remainder of 1708 from the battering that it had taken at Oudenarde. Fully realising this fact Marlborough conceived a plan by which he proposed to bypass the great fortresses of the French frontier and march directly onto Paris. This would cause the garrisons of the frontier fortresses to come out in pursuit, while at the same time Vendôme would also have to follow the Allies, allowing Marlborough to bring on a great battle and finally end the war. Unfortunately Prince Eugene was opposed to the plan, one of the few times he disagreed with Marlborough’s strategy. For his part therefore the Duke was forced to fall back upon a lesser plan, entailing the siege of enemy fortresses. Although this would, if successful, have great strategic importance, it would not end the war.[35]Livesey. Anthony, The Battles of the Great Commanders, page 78

Graham J.Morris

August 2008

Photographs

Photographs taken by Ugo Jansson in 2004.

Panoramas taken in 2008

A) View from Huyse looking west to south.

B) Open ground near Oyke, looking north to west.

C) Open ground near Oyke, looking east to south.

D) 360 panorama near Marolle

References

| ↑1 | Chandler. David, Marlborough as Military Commander, page 183 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid, page 185 |

| ↑3 | Churchill. Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Time, Vol II, page 230 |

| ↑4 | Churchill. Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 230-236 |

| ↑5 | Churchill. Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 254-258 |

| ↑6 | . Churchill. Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 275-276 |

| ↑7 | Chandler. David, Marlborough as Military Commander, page 205-206 |

| ↑8 | Chandler. David, Marlborough as Military Commander, page 206 |

| ↑9 | Chandler. David, Marlborough as Military Commander, page 209 |

| ↑10 | Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 132-133 |

| ↑11 | Dispatches, vi, page 95. Quoted in, Churchill. Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 344 |

| ↑12 | Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 134 |

| ↑13 | Quoted in, Churchill, Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 349

* Churchill and Falkner give 8th July as the date of Eugene’s arrival at Marlborough’s HQ, while Chandler gives the 9th July. |

| ↑14 | Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 135. These troops consisted of several thousand cavalry. This point is worth remembering during the battle. |

| ↑15, ↑17 | Chandler. David, Marlborough As Military Commander, page 214 |

| ↑16 | Churchill. Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 355 |

| ↑18 | Churchill, Sir Winston S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 360 |

| ↑19 | Ibid, page 361 |

| ↑20 | Churchill. Sir Winston, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 362 |

| ↑21 | Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 143 |

| ↑22 | Churchill. Sir Winston S. Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 363 |

| ↑23 | Ibid, page 364 |

| ↑24 | Chandler. David, Marlborough as Military Commander, page 218-219 |

| ↑25 | Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 146 |

| ↑26 | Churchill. Sir Winston. S, Marlborough: His Life and Times,Vol II, page 368 |

| ↑27 | Chandler. David, Marlborough as Military Commander, page 220 |

| ↑28 | Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 149 |

| ↑29 | Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, 150 |

| ↑30 | Ibid, page 151 |

| ↑31 | Churchill. Sir Winston. S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 135 |

| ↑32 | Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days, page 152 |

| ↑33 | Churchill. Sir Winston. S, Marlborough: His Life and Times, Vol II, page 375 |

| ↑34 | Falkner. James, Great and Glorious Days page 154 |

| ↑35 | Livesey. Anthony, The Battles of the Great Commanders, page 78 |