24th June 1859

Oil on canvas, 1863

Click HERE for an interactive panoramic tour from the Spy of Italy and the San Martino Tower.

Introduction

Of all the insurrections, campaigns and battles for the unification, or Risorgimento of Italy, the great battle that took place around the small village of Solferino, just south of Lake Garda, was the most decisive and bloody. Its outcome not only set the seal on the eventual independence of Italy, but also saw the formation of the Red Cross, which in turn would not only provide better care for the sick and wounded engaged in armed conflicts, but also for all who were involved in natural disasters around the world.

Of all the insurrections, campaigns and battles for the unification, or Risorgimento of Italy, the great battle that took place around the small village of Solferino, just south of Lake Garda, was the most decisive and bloody. Its outcome not only set the seal on the eventual independence of Italy, but also saw the formation of the Red Cross, which in turn would not only provide better care for the sick and wounded engaged in armed conflicts, but also for all who were involved in natural disasters around the world.

Previous campaigns in Italy had not differed much since the days of Napoleon I. The Austrian field marshal, Josef Graf von Radetzky had out – manoeuvred the Sardinian [1] The dukes of Savoy became kings of Sardinia in 1720; thereafter they acquired Piedmont in 1748. A central government was set up in Turin. army under King Charles Albert in 1848 and 1849 by using interior lines and turning movements that either defeated each portion of their army in detail, or drove them away from their lines of communication. The problem in 1859 was that neither the Austrians, nor the French and Piedmontese were capable of producing a commander who fully understood military science, as well as the proper handling of large bodies of troops over an extended area and during a battle. At Solferino all three armies were led by their respective monarchs with no experienced chief of general staff to assist them in their decision making, unlike the Prussians who were developing a highly trained staff capable of planning their armies movements with great precision. Thus the battle of Solferino became a soldiers’ battle, with hardly any inspiration filtering down to the ranks from their leaders, none of whom at the outset of the engagement were aware of the proximity of the others forces until they were virtually on top of each other.

Previous campaigns in Italy had not differed much since the days of Napoleon I. The Austrian field marshal, Josef Graf von Radetzky had out – manoeuvred the Sardinian [1] The dukes of Savoy became kings of Sardinia in 1720; thereafter they acquired Piedmont in 1748. A central government was set up in Turin. army under King Charles Albert in 1848 and 1849 by using interior lines and turning movements that either defeated each portion of their army in detail, or drove them away from their lines of communication. The problem in 1859 was that neither the Austrians, nor the French and Piedmontese were capable of producing a commander who fully understood military science, as well as the proper handling of large bodies of troops over an extended area and during a battle. At Solferino all three armies were led by their respective monarchs with no experienced chief of general staff to assist them in their decision making, unlike the Prussians who were developing a highly trained staff capable of planning their armies movements with great precision. Thus the battle of Solferino became a soldiers’ battle, with hardly any inspiration filtering down to the ranks from their leaders, none of whom at the outset of the engagement were aware of the proximity of the others forces until they were virtually on top of each other.

The War of 1859.

(Museo San Martino)

After his failed attempt to assassinate Napoleon III in 1858, Felice Orsini, the Italian liberal, wrote a letter from his prison cell urging the French Emperor to support Italy in her struggle for independence, a subject never far from Napoleon’s thoughts as he had been a member of the Carbonari when young, and had always harboured the idea of, ‘sovereign states based on racial and linguistic unity collaborating in the general purpose of prosperity and peace.’ [2]Gooch. G.P, The Second Empire, page 21 At a meeting with Piedmont’s Prime Minister, Camillio Carvour at Plombiéres in July 1858, Napoleon agreed to join Italy in a war against Austria. If successful Piedmont would gain Lombardy, Venetia and the two Duchies of Modena and Parma, with France gaining Savoy and Nice in gratitude for her assistance, the rest of Italy would remain the same. It was also proposed that the enfant terrible, Prince Napoleon, or Plon-Plon, as he was known in the family, the son of Jerome Bonaparte and Catherine of Wurttemburg should marry the Princess Clothide, daughter of Victor Emmanuel, thus cementing the alliance. Cavour would provoke Austria into becoming the aggressor by stirring up trouble in Lombardy, thereby enabling the French to intervene without ruffling the feathers of the other great powers. All of this almost came to nothing when Austria showed extreme caution when Cavour’s planned insurrection was triggered off.

Expecting an immediate Austrian response, Victor Emmanuel had ordered the mobilisation of the Piedmontese army in March 1859, and much to his chagrin he now realised that with no sign of Austrian retaliation forthcoming he would be isolated since the French would only intervene if Franz Joseph tipped his hand and became the aggressor. As it turned out the Austrians shot themselves in the foot by sending an ultimatum to the Piedmontese demanding immediate demobilisation of their army, this in turn was curtly rejected allowing the French to intervene on the side of Piedmont, while Austria was now seen as the aggressive party in the eyes of Europe.

The French Army

Click here French order of battle

One of the main problems with the French army at this time was the scattered nature of its various components, and although seen by most as the finest army in the world, particularly due to its exploits during the Crimean War and in Algiers, it had changed drastically since the heady days of the First Empire and now, ‘…the structure, organisation and method of recruitment were based on a conscious denial of all that the Revolutionary and Napoleonic armies had stood for. Neither the restored Bourbons nor the Orléanists had wished ever again to unkennel the mob.’ [3]McElwee. William, The Art of War, page 34

The French Ministry of War proved totally inept when it came to its estimates for the troops available for the Italian campaign. At most they could put together just 200,000 men, while a further 50,000 were needed in Algeria, and another 6,000 were used to support the Papal government in Rome. This supposedly left 200,000 troops in eleven infantry and two cavalry divisions scattered around France for home defence. But these were not all first line regiments, and consisted mainly of garrison and fortress troops together with depot maintenance parties. [4]Ibid, page 36 Luckily for Napoleon III Prussia was not able to move more swiftly to the aid of Austria in 1859; had she done so the French Emperor may have been crushingly defeated on the Rhine?

In the eighteen thirties, during his tenure as French Minister of War, Marshal Soult had considered the formation of elite chasseur companies armed with rifled carbines that would be able to use their athletic-style training to move faster on the battlefield, and although none of these companies ever materialised, the idea of fast moving and agile troop formations was taken up by the Duc d’Orléans who raised a company of chasseurs which, in 1838 was increased to full battalion strength and became known at the Tirailleurs de Vincennes. [5]Nosworthy. Brent, The Bloody Crucible of Battle, page 53-54

The manoeuvring of these troops was totally different from that of the line regiments in that they were trained to perform all manoeuvres at the double quick, or at what became known as the gymnastic pace, which was very fast, and ranged from 165 paces per minute up to a positively breathtaking 180. While campaigning in North Africa they were brigaded with the native Zouaves, and the two units soon became very efficient in dealing with Arab long range sniping and hit and run tactics. [6]Ibid, page 57 In 1840 a further nine battalions were raised and their name was changed to the chasseurs à pied. By 1845 Marshal Thomas Bugeaud authorised the publication of a manual, “Instructions for the Evolutions and Manoeuvres of the Foot Chasseurs.” Forthwith all battalions of light infantry would manoeuvre at the gymnastic pace without interruption, from closed column to line, without having to go through the ten separate commands employed for the line battalions. [7]Ibid, page 397-398

The line infantry themselves still used a basic mixture of column and line. However, the massive columns of attack that had been employed at such battles as Wagram and Waterloo during the Napoleonic Wars were abolished and, thanks to the writings of the Swiss born military theorist, Baron Antoine Jomini (1779-1869) in his work, Precis de l’art de la guerre, published in 1838, the offensive was now carried out in deployed line, reinforced either at the centre or on either flank by battalions in company column. Jomini also considered that any attack should be made en echelon using a V or “inverted V” formation. Light troops advanced in front of the attacking formation in skirmishing order. [8]Quoted in, Nosworthy. Brent, The Bloody Crucible of Courage, page 59

The introduction of the rifled musket caused Napoleon III and his generals to consider the practicability of long-range rifle fire on the battlefield. Since the French now had most of their light battalions armed with the Minié rifle, it became apparent that unless kept under strict control, these troops could start firing at long range thus using up a great deal of ammunition. As General Bonneau du Martray stated:

As no one doubts that the rifle will play a much more important part in success of future battles than hitherto, it is the utmost importance to train good shots. We say, in the first place, that the use of the elevating sight is too slow and too difficult in battle; it will even cause the loss of some of the advantage of breech loading. The determination of distance, and, consequently, the adjustment of the sight, are liable to error, and the time required endangers the loss of the favourable moment for firing…We think, therefore, that in the field we should abolish the use of the backsight. It is not absolutely necessary to hold the rifle at the shoulder to make good practice in firing. [9]Nosworthy. Brent, The Bloody Crucible of Courage, page 282

One can see from all the above that the French still considered élan on the battlefield to be more important than rifle training, and that the bayonet was still the weapon most to be relied upon in deciding the issue.

The French cavalry, like most of their European counterparts, were still used for shock action and information gathering, although the latter was, to say the least, abysmally carried out by all three armies during the Italian campaign. All regiments were armed with the Delvigne or other equivalent rifled carbines, which were supposed to allow the light cavalry in particular to act as skirmishers, but the main role of mounted troops was in the attack, carried out by massed squadrons employing a “raking charge” when attacking enemy infantry in line; this called for them to approach the enemy from the right, that is on the sword or lance arm, so that they could avoid the destructive fire of the new rifled musket, and once closed on their opponents they were to ride along the front slashing and spearing, causing as much confusion as possible. [10]Ibid, page 74

Like his famous uncle, Napoleon III was a keen advocate of artillery, with a sharp eye for new developments in the field of ordnance. The French therefore were able to take the field armed with 12 pound cannon, and the new 4 pound Beaulieu rifled guns, which far outclassed the Austrian smoothbore.

The Austrian Army

Click here for Austrian order of battle.

Allowing for the fact that the Austrians would be fighting the campaign over familiar ground, they nevertheless were at a distinct disadvantage when it came to mobilisation and supply. Like the French their forces were stretched even during peacetime owing to the commitments of trying to cover their straggling empire. Divided into four Army Commands, the strongest was the 2nd Army with three under strength corps in northern Italy and along the coastal areas around the Adriatic Sea.

Also like the French, the Austrians had problems with the “real” strength of their available forces, and the numbers conjured up on paper. There were never more than some 220,000 men available in Lombardy, Istria and Dalmatia, and at the decisive battle of Solferino Franz Josef could scarcely scrape together 120,000 men, ‘Clearly Austria’s failure to preserve her pre-eminence in Italy and Germany sprang from largely the breakdown of her army organisation and her recruiting system.’ [11]McElwee. William, The Art of War, page 51

The Austrian officer class was also to show how indolent it had become in understanding any new proposals placed before them. When asked by the Prussian military attaché in Vienna in 1854 if his Austrian colleagues were interested in Kriegsspiel, used to train Prussian staff officers, he found that once they became aware that it was not a game played for money they lost all interest. [12]Craig. Gordon .A, The Battle of Königgrätz, page 25

In 1859 the Austrian infantry were armed with the Lorenz rifled musket, but their Jäger battalions were the only ones who really became proficient in its use. This was to prove a great handicap as the new rifle could have given them the edge in defensive tactics, and could have been a decisive factor in breaking the French attacks had it been used in more skilled hands. But the Austrians still clung to outdated manoeuvres on the battlefield, preferring compact battalion columns and the bayonet to the detriment of all else.

Austrian cavalry was arguably the finest in Europe at this time. Mounted on Hungarian horses, the heavy cuirassier regiments were well trained and led, while the light cavalry divisions consisting of dragoons, hussars and uhlans (lancers) proved themselves far superior to anything the French could bring against them. [13]Craig. Gordon. A, The Battle of Königgrätz, page 22

All Austrian artillery was smoothbore, consisting of 12 and 6 pound cannon plus howitzers, basically unchanged since the Napoleonic Wars. In addition each field artillery battery had a rocket section attached to it, though exactly what these weapons actually achieved is debatable. Tests were inconclusive, and no military artists who depicted the battle scenes of 1859 and 1866 ever seem to show them in action.

The Sardinian/ Piedmontese Army

Click here for Sardinian order of battle.

The Sardinians had proved their worth during the Crimean War where her small but well disciplined army gained much respect from both the British and French after its performance on the Chernaya River. In 1859 it numbered some 30,000 men, which was raised to 70,000 when all reserves were called to the colours. Frederick Engles gave a glowing account of them in 1855 when he wrote:

The Piedmontese army is as fine and soldier-like a body of men as any in Europe. Like the French, they are small in size, especially the infantry; their guards do not average even five feet four inches; but what with their tasteful dress, military bearing, well-knit but agile frames, and fine Italian features, they look better than any body of bigger men. …The percussion- musket is the general arm of the infantry; but the Bersaglieri have the short Tyrolese rifles, good and useful weapons, but inferior to the Minié in every respect. [14]Engles. Frederick, The Armies of Europe, page 8

The force available for immediate action consisted of five infantry divisions and one cavalry division, supported by 90 guns.

Tactics for the infantry were along Austrian lines, although some changes were taking place in the use of company columns and more linear formations.

The cavalry consisted of dragoons, lancers, hussars and carabineers, and the lance itself may have been carried by the first rank of each squadron in all regiments. [15]Engles. Frederick, The Armies of Europe, page 7 Battlefield tactics were the same as the French and Austrian, together with the failure in reconnaissance that plagued both those armies.

The artillery remained smoothbore, having 16 pound and 8 pound cannon and 15cm Howitzers mounted on the “Cavalli” gun carriage. The “voloira” or flying artillery consisted of light 6 or 8 pound cannon and was much the same as the French horse artillery.

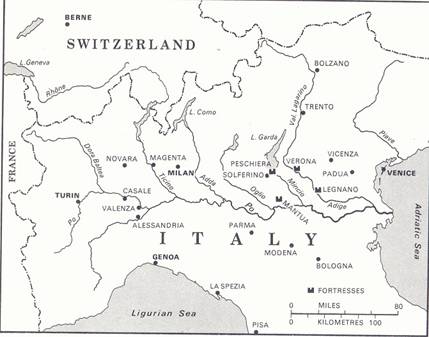

The Theatre of War.

The fertile plain of Lombardy over which the campaign was fought was intensely cultivated. The countryside abounded in vineyards, rice and maize fields as well as orchards, many of which were intersected by irrigation channels. To the south flowed the Po River, while to the north the ground climbed steadily towards the majestic Alps. Although the main roads were good, the smaller arterial country roads were no more than rutted tracks, full of potholes that became virtually impassable during heavy rainstorms. Many tributaries of the Po River bisected the countryside from north to south and included the Sesia, Ticino, Adda and the Mincio. These rivers, although not great obstacles in themselves, could be used as fall-back lines and strategic concentration points for armies manoeuvring across the plain.

Opening Moves.

The Austrian 2nd Army was commanded by Feldzeugmeister Ferenc Graf Gyulai. At 65 years of age he was certainly not in the same league as Radetzky. By moving swiftly he would have had the chance of knocking out the much smaller Piedmontese army before the arrival of the French. But Gyulai erred on the side of caution. On April 29th, with close to 120,000 men and over 300 cannon the Austrian commander crossed the Ticino River and spread out his men along the Sesia, pushing troops out as far as Vercelli. Here he wasted precious time for no apparent reason other than the fact that he was in awe of the name of Bonaparte. He was aware that the French were already pushing forward towards the Mont St. Cenis pass, as well as sending troops to the port of Genoa in steamships. This threat alone caused Gyulai to become obsessed with any turning movement that might occur on his left flank. [16]Brooks. Richard, The Austro-Sardinian War, The History Net

What Gyulai was not aware of was the chaotic state of the French mobilisation and concentration. With no idea of how to deal with the mass movement of troops and supplies by rail or ship, with no forward planning being made beforehand, or study of the complexities of the logistics involved, it was only by sheer good fortune, coupled with the equally disorganised state of her opponent that the whole campaign did not turn into a fiasco. McElwee gives a graphic account of the chaotic state of the French army and administration when it was known that war had been declared:

The result of this “fainéantisme” were as ludicrous as might have been expected, though serious for the troops concerned. As early as 10th March 1859, as a result of rumours of Austrian concentrations on the Piedmont frontier, the War Ministry was instructed to form at Briançon an advance-guard division under General Bourbaki ready to move at twenty-four hours notice to Turin. The order did not go out to Marshal de Casrellane at Lyons until 17th April; and only then was it realised that Bourbaki was still, in sublime ignorance of his future, commanding his garrison at Besançon, while his two designated Brigade Commanders, Generals Durcot and Trochu, were similarly employed at Orléans and Paris. The Austrian three- day ultimatum which precipitated the war left Vienna on 19th April. Only on the 21st did Napoleon formally order the creation of the five Army Corps which, with the Guard, were to form the Army of Italy. Two days after that Marshal Canrobert arrived at Lyons at ten o’clock at night to take over command both of his own III Corps and Niel’s IV Corps for crossing the Alps by the Mt Cenis and Mt Genévre passes. He found an order awaiting him to cross the frontier forthwith, but received almost immediately a telegram from Bourbaki, his advance-guard commander, which ran: ‘The troops of my division are without blankets. It is cold. We have neither tents nor water-bottles, nor camp equipment, nor cartridges. There is no hay. Absolutely nothing necessary for the organisation of a division has been sent here.’ The only answer Canrobert could get from his own protest to the War Ministry was a terse telegram from the Emperor himself: ‘ I repeat my order that the frontier is to be crossed forthwith.’

On 26th April the harassed marshal, who had since been ordered to proceed at once to Turin with General Niel to co-ordinate movements with the King of Sardinia, sent a telegram to the War Ministry which summed up all the frustration and grievances of his brother generals: They have forgotten to provide for my Army Corps operational staff, Q staff, provost, medical services, artillery, and engineers…’ The only satisfaction he got was a postscript to a personal letter from the Minister of War transmitting the Emperor’s orders for his preliminary movements on arrival in Italy: ‘I note with distress.’ Marshal Vaillant wrote, ‘that your troops are not organised for war. You will be putting this right.’

The pattern was everywhere the same. The army arrived in Italy well ahead of all the equipment and supplies needed for a campaign which had already begun –‘ the opposite,’ as the Emperor telegraphed to Marshal Randon, the new Minister of War, ‘of what we should have done.’ He added that he held the Ministry ‘very much to blame.’ But he himself shared with his ministers and officials the cheerful French belief that somehow things would sort themselves out. When he gave out his first orders, for the general advance of the Allied Army, and Marshal Baraguay-d’Hilliers protested that neither I nor II Corps had yet got artillery, he shrugged the matter off: ‘On s’organisera en route.’ That might have stood as the motto of the whole supply service, the “Intendence.” The ammunition and rations piled up at Genoa because there were no officers with experience or energy to get such large masses of material moving on the largely one-track railway lines. By local purchase or requisition, and with the help of hastily organised civilian transport columns, the army was somehow fed and kept on the move, though at the cost of great hardship to the troops. Worst of all, on the final day of the battle of Solferino, where the horrible suffering of the wounded precipitated the foundation of the Red Cross, the French medical supplies were still piled up on the docks. The much-vaunted professionalism justified itself in that the French troops outfought the Austrians and by the narrowest of margins won both the great battles for their Emperor. The commanders and staffs were saved from total discredit only by the French genius for improvisation and the still greater incompetence of the Austrians.’ [17]McElwee. William, The Art f War, page 40-41

Arriving ahead of his troops Canrobert met with Victor Emmanuel and at once advised the king to move his army from covering the capitol and concentrate with the French forces at strong fortified positions around Alessandria. Between the 1st and 3rd of May this concentration was implemented, with the Piedmontese being joined by the French III corps, and on the 7th of May by the IV corps. Thus if Gyulai still persisted with an advance on Turin his lines of communication could be threatened by a turning movement on his left flank. All of this gave the Austrian commander the jitters, and possibly recalling the campaign of 1796 when the young general Bonaparte had used similar tactics in defeating the Austrians, Gyulai pulled his forces back across the Sesia River from their advanced position around Vercelli, regrouping around Mortara. He knew that another Austrian army was being formed, The First, consisting of the 1st, 2nd and 11th corps, and that these troops were now mobilizing with some units already arriving in Italy, therefore a defensive stance seemed in order while awaiting events.

By the 16th May the French I corps was concentrated around Voghera and Pontecurone, with the II corps at Sale and Bassingana. The III corps took position at Tortona, and the IV corps at Valenza. The Imperial Guard where grouped around Alessandria. The Piedmontese army took ground between Valenza and Casale. Prince Napoleon’s V corps, which acquired the sobriquet, “The Fifth Wheel” because it never seemed to do much, was away in the duchies of central Italy on a diplomatic mission, with the exception of one division still with the main French army. [18]1911 encyclopedia.org/Itailan Wars Thus when the French Emperor arrived to take command, he had at his disposal close to 200,000 men against Gyulai’s 120,000.

Believing that the concentration of the French and Piedmontese armies portended a thrust in the direction of Piacenza, Gyulai ordered a reconnaissance to be carried out towards Voghera. This force, commanded by Count Stadion, comprised of the Austrian 9th corps together with elements of 5th corps, some 25,000 men and 60 cannon. On 20th May the Austrians pushed back the Piedmontese cavalry outposts at Casteggio and moved forward through the village of Montebello towards Genestrello. Here they encountered the forward elements of the French division under General Forey (I corps), numbering 8,000 men and 12 guns. Forey’s aggressive tactics, in which he fed fresh battalions into the battle as they came on the field, caused the eventual withdrawal of Stadion’s battered columns with the loss of over 1,300 men, at a cost to the Allies of 700. Despite having superior forces in close proximity to the battlefield, the Austrian used only half of their available manpower, and never even managed to deploy more than 16 of their 60 cannon.

Rather like two people bumping into one another in a dark room, both the French and Austrians fell back on the defensive. It became obvious to Napoleon III that the cautious nature of his opponent meant that any chance of turning the Austrian left flank would be met with strong resistance, since Gyulai had piled up considerable forces to cover such an eventuality. Therefore a new plan was set in motion whereby the Franco-Sardinian armies were to move towards Novara, and from there make a push to take the Lombardian capitol of Milan. On 30th May the Piedmontese crossed the Sesia River taking the town of Palestro after a hard struggle. The following day the Austrians counter attacked, but after a bitter see-saw battle were repulsed. It was during this encounter that Victor Emmanuel, showing conspicuous bravery in leading the French 3rd Zouaves, was awarded the rank of corporal in the regiment. What the king thought of this “honour” does not seem to have been recorded.

By the 2nd of June the allied armies had moved forward with the French IV corps occupying Novara where it was joined by the II corps and the Imperial Guard. The Piedmontese army, together with the French I and III corps were at Vercelli, pushing out cavalry patrols toward Vespolate. Suddenly realising that he had been outmanoeuvred, on the evening of the 3rd of June Gyulai pulled back across the Ticino River to positions around Magenta, covering the approaches to Milan. For his part the French Emperor, without any clear knowledge of the whereabouts of the Austrian army, ordered the crossings of the Ticino to be secured, and placed his forces on both sides of the river so as to meet any threat towards Mortara or Vigevano.

On the afternoon of the 4th of June the advancing French columns once again collided with Gyulai’s advance posts, who were as surprised at the sudden meeting as their adversaries. Soon a full-blown engagement had developed in which both sides were unable to deploy either their artillery or cavalry to good effect owing to the closed nature of the terrain. The poor coordination of the various Austrian corps allowed the French to finally gain the upper hand, and by nightfall Magenta was in their hands. The battle cost the Austrians almost 10,000 men in killed wounded and missing, while the French losses numbered close to 5,000.

After the battle of Magenta the Austrians began to withdraw towards the Quadrilateral – their old enclave of the mutually supporting fortresses of Mantua, Peschiera, Verona and Legnago. On June the 8th Victor Emmanuel and Napoleon III entered Milan in triumph. On the same day the French attacked the Austrian rearguard at Melegnano, but due to a total lack of coordination in planning their attack they allowed the Austrians to retire in good order.

The general consensus of opinion for the French and Piedmontese was that since the Austrians had fallen back across the Mincio River to the shelter of the Quadrilateral, they would remain there and offer battle on more favourable ground to themselves. However, when the young Emperor Franz Joseph joined his troops he immediately dismissed Gyulai and took overall command himself, and having now collected together seven army corps in two armies; the 1stArmy, with the 3rd, 9th and 11th corps, together with the cavalry division of Count Medtwitz, and commanded by Feldzeugmeister von Wimpffen; the 2nd Army consisting of the 1st, 5th, 7th and 8th corps with Baron von Mensdorff ‘s cavalry division was commanded by Count Schlick. It would appear that although Franz Joseph himself was content to await the advance of the allied armies behind the Mincio, he was persuaded by his chief of staff Feldzeugmeister Count von Hess to go back on the offensive. The bridges over the Mincio were still intact and further pontoon bridges were also laid across the river to facilitate the advance of the Austrians. Unfortunately what the Austrian Emperor was unaware of was that the French and Piedmontese had also decided on offensive operations. On the 22nd June Napoleon III was at Monte Chiaro with Victor Emmanuel’s army to the north, covering his left flank west of San Martino, with the main bodies of both armies already moving to the crossing points of the Chiese River.

The Battlefield.

The ground over which the decisive battle was fought consisted for the most part of rolling meadowland, interspersed here and there with large farms and villages, each of which was surrounded in turn by cornfields, vineyards and orchards. The northern sector of the battlefield was confined by Lake Garda, and ran from Rivoletta to Peschiera, while to the south it terminated in a rough line running from Castel Goffredo to Volta. To the west, or allied side of the battlefield, the ground rose from Lonato in a series of rounded hills and hummocks towards the town of Castiglione. These heights then curved around towards the east, becoming steeper as they approached the villages of Solferino, Cavriana and Volta, before petering out at the banks of the Mincio River. To the south west of Cavriana the ground fell away to the plain of Medole, which was excellent manoeuvring country, especially for cavalry.

The village of Solferino itself was conspicuous from miles around owing to its medieval tower, the Spia d’Italia (Spy of Italy), perched on the summit of the Bocca di Solferino, from the top of which the whole countryside could be viewed. At the entrance to the village from the west stood a walled cemetery and the church of San Pietro. A little to the north, separated from the village by a steep sided cutting was a small hill planted with Cyprus trees, the Mont des Cyprées, which covered the approaches to the cemetery and village from that direction. These elevations, together with the walled village of Cavriana to the south east, also situated on high ground and covered by the slopes of Mount Fontana, formed natural redoubts. From Solferino, in the direction of Rivoltella, the landscape was mainly flat with the exception of two ridges, one at San Martino, and the other at Pozzolengo. About one mile to the north of the village of San Martino the main railway line from Milan to Verona crossed the plain.

Considering the fact that the Austrians knew the ground well, having carried out manoeuvres in this area on numerous occasions, and benefiting from entrenchments already prepared during these military exercises, it seems strange that they apparently had no measured range markers already in place for homing-in their artillery? [19]Turnbull. Patrick, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation, page 120. Turnbull mentions concealed and well-sighted gun positions but makes no mention of range markers. (Authors note)

Views from the Spy Of Italy

Looking North across the Castle. The San Martino tower is just off the right hand edge of the photograph. Lake Garda and the Alps in the distance.

The Battle.

Just how many troops in all three armies were present on the battlefield is debatable; all sources relating to the battle giving different figures. Some Italian descriptions state 135,000 French and Piedmontese and 140,000 Austrians. [20]Sociéta Solferino e San Martino, pamphlet, San Martino della Battaglia Museum. The booklet published by the Comunita’ Del Garda gives 300,000 infantry and 26,000 cavalry, with 1,500 cannon as the combined total. Yet another source, Dr Vitantonio Palmisano, has 80,000 French, 30,000 Piedmontese, and 90,000 Austrians. [21]Meglegnano website. French and German sources range from 300,000 to as little as 180,000, while in English H.C.Wylly in his work, The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, puts the Austrians at 189,648 infantry, 22,000 cavalry, with 752 cannon; the French and Italians, 173,603 infantry, 14,353 cavalry, with 522 cannon. [22]Wylly. H.C, The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 133-134 Patrick Turnbull, who seems to have looked at Wylly’s estimates, agrees with the numbers for the French and Piedmontese but decided to take off a few from the Austrians, giving them a total of 146,000 infantry, skipping the cavalry numbers and stating that they had 88 squadrons. [23]Turnbull. Patrick, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation, page 124 Given that all three armies had been engaged in many heavy skirmishes and a major battle, and allowing for the Austrians having been reinforced by fresh troops, although still not probably all at full regimental strength, then a fair estimate would be around 120,000 effectives, with 500 cannon. The French and Piedmontese I consider, after much head scratching, probably fielded no more than 130,000 men, with 400 cannon.

On the 23rd June Napoleon III issued orders for the offensive drive to commence at 3 a.m. the following morning. The Ist Corps, commanded by Marshal Baraguey d’Hilliers to march from Esenta to Solferino; IInd Corps, commanded by General Maurice de MacMahon from Castiglione to Cavriana; IIIrd Corps, commanded by Marshal François Certain Canrobert from Mezzane to Medole; IVth Corps commanded by General Adolphe Niel, together with the cavalry divisions of General Patouneaux and General Desvaux, from Carpendolo to Guidizzolo. The Emperor’s Headquarters were at Castiglione with the Imperial Guard commanded by General Saint Jean d’Angely. The army of Victor Emmanuel to move towards Pozzolengo, their 2nd Division (General Fanti) on the right keeping in contact with the French Ist Corps.

On the morning of the 24th June the Austrians were also moving forward on the offensive. Orders to Second Army, commanded by Feldzeugmeister Count von Schlick, to cross the Mincio River; 8th Corps (Benedek), together with a detached brigade from 6thCorps, to move on Pozzolengo; 5th Corps (Count Stadion) to move on Solferino; 1st Corps (Clam- Gallas) to cross the river at Valeggio and move on Volta and Cavriana; 7th Corps (Zobel) to move on Foresto; the cavalry division (Mensdorff) to move in the rear of 7th Corps heading to the east of Cavriana.

Orders to First Army, commanded by Feldzeugmeister Count von Wimpffen, forming the left of the Austrian formations. To remain refused to protect Goito from any enemy advance. When the movements of the Second Army has developed the 3rd Corps (Schwartzenberg) will cross the Mincio and move on Guidizzolo; 9th Corps (Schaffgotsche), crossing the river at Goito will also move on Guidizzolo with the cavalry division (Zedtwitz) protecting the left flank towards Medole, pushing out detachments towards Casaloldo and Castel Goffredo; 2nd Corps (Liechtenstein) after detaching two brigades to join the 11th Corps, will move on Marcaria. The Emperor Franz Josef’s Headquarters was at Valeggio. [24]Wylly. H.C., The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 131- 132.

In his work, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation, Patrick Turnbull states that the possible reason why Allies and Austrians failed to know each others whereabouts, even though they were in close proximity of one another, was due to freak weather conditions, in particular a heat wave that sent the temperatures soaring to well over 35c. In fact the temperature in northern Italy during the month of June can be very high without any “freak” heat wave to help it along. There was indeed a recorded heat wave for 1859, but that took place in July, not in June, and was one of the hottest ever on record. [25]I am grateful to Roger Brugge who supplied the weather details for 1859. Besides this, one fails to see how heat would affect good reconnaissance and information gathering by well-trained light cavalry? It all seems to come down to the fact that neither side had a clue what the other was doing. Such things had happened before. To give just one example; during the Austrian campaign of 1809, Napoleon had crossed the Danube River forming his advanced forces in a very constricted area between the villages of Aspern and Essling. Although both villages had church spires with excellent visibility across the billiard – table flatness of the Marchfeld plain, and the French had light cavalry outposts out covering the approaches, the vast Austrian army under Archduke Karl, numbering over 100,000 men, was not detected even though they were only a few miles away.

As Napoleon III was preparing to move with his staff from Monte Chiaro to Castiglione, at around 7 a.m. on the morning of the 24th June, he was met by one of MacMahon’s aides on a sweating horse who informed him that the Austrians were concentrating on the very ground which the French Emperor had ordered occupied by his own troops. Arriving in the town square of Castiglione, Napoleon climbed the church tower and was passed his Lemaire field glasses. Focusing onto the distant hilltops around Solferino and Cavriana he at once saw that these formidable heights, as well as the ground stretching away to the south was covered with the white uniforms of the Austrian infantry, and that other masses were rapidly approaching. Now fully realising that his original plans had been relegated to the litterbin, Napoleon decided that although the cost would prove high, he had no alternative other than to try and storm the high ground now crammed with the enemy about Solferino and attempt to split the Austrian line in two.

The battle had actually started at around 5 a.m. in the morning when the Austrian outposts at Morino, north east of Medole, had been engaged with elements of Luzy’s French division (Neil’s IVth Corps). This soon escalated into a full-blown struggle for possession of Medole itself, as Luzy committed more troops to the attack, finally forcing the two regiments of the Austrian 52nd regiment (9th Corps) together with two cannon out of the village. Further to the south Canrobert’s IIIrd Corps was approaching Castel Goffredo at around 7 a.m., and hearing the rumble of cannon around Medole he dispatched Renault’s division towards the village. Stationed to the rear of Medole, Lauingen’s Austrian cavalry brigade had been placed in support, but that general, considering the ground to be unfavourable for cavalry ordered a retirement towards Ceresara, and finally fell back to Goito where he remained taking no further part in the action. As if this was not bad enough General Zedtwitz, who commanded the cavalry division on this wing, also decided to ride off in search of Lauingen’s meandering brigade with the consequence that the Austrian left flank was deprived of its mounted arm for almost the whole day. [26]Wylly. H.C. , The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 141

Meanwhile at around 7.30 a.m. Napoleon III was about to set in motion his assault on Solferino, with Marshal Baraguey d’Hillier’s Ist Corps, supported by MacMahon’s IInd Corps. Meeting the French Emperor MacMahon informed him of large enemy columns advancing on Guidizzolo and Cavriana with still more hostile battalions heading towards Medole. He also voiced his concern about the widening interval that was being created between his corps and that of Neil’s, which had pushed on rapidly and was in danger of becoming isolated. Considering the situation Napoleon ordered the Guard cavalry to plug the gap while MacMahon grouped his corps so as to cover Casa Marino on his left and Cassiano on the right.

The Austrians were indeed approaching in great strength towards the void spotted by MacMahon, but once again a total lack of coordination caused them to fritter away the golden opportunity of severing the French line. Here the 9th and 3rd Corps where closing on Casa Marino, and the 1st Corps establishing itself in Cavriana, with troops thrown forward into Cassiano. But instead of pressing on Schaffgotsche, the commander of the 9th Corps detached his second division (Crenneville) to Medole, and three brigades from his first division (Handl) on the Rebecco- Medole road, sending the other brigade towards Ceresara. This left Schwartzenberg’s 3rd Corps as a rather blunt spearhead in the advance on Castiglione. To cap it all Schwartzenberg’s brigades, supposedly due to the difficult terrain it had to contend with, began to drift apart, and came into action piecemeal. [27]Wylly. H.C., The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 142. Once again this does not say a great deal for how much the Austrians had learnt about the ground during all their peacetime manoeuvres.

At 9 a.m.the fighting around Medole had flared up again as Crenneville moved towards the village, only to be hit on his left flank by the Vinoy’s French division (IVth Corps), while sustaining heavy fire from Luzy’s troops on the right, halting its progress and forcing it to take up a defensive position across the Mantua- Castiglione road confronting Vinoy’s division. Handl’s brigades had also become widely separated owing to the nature of the ground, with one brigade engaging Luzy’s division and another further south running into Lenoble’s French brigade (IVth Corps). Handl’s third brigade had already fallen back in some disorder to Guidizzolo after suffering a pounding from the French artillery.

In the centre Marshal Baraguey d’Hillier’s Ist Corps, with Ladmirault’s First division leading, came towards Solferino at 6 a.m. Finding the village strongly held Ladmirault formed his troops into three attacking columns, sending one to attack frontally, while the other two came in on each side endeavouring to outflank the defenders. D’Hillier’s Second division (Forey) supported the attack, with the Third division (Bazaine) in reserve. However Napoleon was far from happy at not being able to administer the massive strike he had intended owing to Niel’s commitment around Medole and MacMahon’s slow progress at Cavrinana, which was stoutly defended. Unlike his renowned uncle however, Napoleon III did not hoard his mass of decision –The Imperial Guard. By 10 a.m. the French, after some severe fighting forced back the outlying Austrians holding positions in advance of Solferino, and were able to push forward several batteries of artillery to take-on the enemy gun emplacements around the village. Knowing full well that an attack was imminent the Austrian 5th Corps commander (Stadion) had informed Count Schlick that a major assault was imminent, to which the Second Army commander perforce moved up units of the 1st and 7th Corps for close support, and ordered Mensdorff’s cavalry division towards the open ground between Cassiano and Casa Morino to contain any turning movement in that direction. [28]Wylly. H.C., The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 144.

View of the Mont des Cyprées

Progress was slow and bloody with Ladmirault’s and Forey’s regiments receiving a severe pounding as they attempted to gain a toe hold on the fire belching heights, but fresh troops were now available in the form of Bazaine’s Third Division, which Baraguey was able to throw into the fight, as the French Emperor moved forward himself to the fighting line with the two divisions of Imperial Guard infantry. On the Austrian side, despite the protection offered by buildings and entrenchments casualties were mounting, with no sign of any abatement in the assaults of the enemy. In fact the French were making ground, for with outstanding courage and at a great cost in life they had managed to bring forward a battery of artillery onto an outlying rise of ground only 300 meters from the cemetery of Solferino, which caused extensive damage to the surrounding walls. [29]Ibid, page 144. From a poem written in his honour in 1849

(Museo San Martino)

To the north the Piedmontese started their advance towards Pozzolengo sometime around 6 a.m. in the morning, probing through a thin veil of mist that drifted inland from Lake Garda. They were soon brought up short by four Austrian brigades, which had been placed on the hills above the town by the 8th Corps commander, Lieutenant Field Marshal Ludwig August von Benedek ‘Radetzky’s Number Two.’* The faulty distribution of the Italian divisions allowed each to be driven back by vigorous Austrian counter attacks as far as San Martino, but realising that he probably had the better part of Victor Emmanuel’s army before him, Benedek ordered his brigades to fall back and regroup while he brought forward his two reserve brigades that had been stationed to the east of Pozzolengo. At 8.00 a.m. the Austrians again took the offensive, pushing forward three brigades which, after bitter fighting managed to establish themselves on the San Martino ridge.

Fully intending that his army would not play second fiddle to the French as they had done at Magenta, Victor Emmanuel ordered Cucchiari’s 5th Division, supported by a brigade from Mollard’s 3rd Division, to retake the heights, and sometime between 9.30 and 10 a.m. the Italian columns, approaching from Rivoltella, stormed the Austrian position. The fighting became severe, with the Italian troops briefly gaining ground only to be forced back across the railway line by a heavy Austrian counterattack. For the next two hours no other attempt to storm the strongly held position around San Martino was attempted, with both sides regrouping while maintaining a constant duel of artillery fire, Benedek being content to hold his ground rather than expose his left flank by going over to the attack.

While the struggle around San Martino was taking place the Piedmontese 2nd Division, commanded by General Fanti, was approaching the battlefield from the direction of Malocco. Originally given orders to support Marshal Baraguey d’Hilliers attack on Solferino by Napoleon himself, Fanti now received a message from Victor Emmanuel directing him to march north to support the other Italian divisions confronting Benedek’s 8th Corps, placing one of his brigades under the orders of General Mollard, and with the remaining brigade move on Madonna della Scoperta to give assistance to General Durando’s 1st Division. [30]Wylly. H.C., The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 146

By 11 a.m. Ladmirault’s division (I Corps), after repeated attempts to gain the Solferino heights, and having incurred heavy losses, was pinned down to the north of the village by Austrian infantry and artillery dug in on the Mont des Cyprées. Every attempt to get to grips with their adversaries was foiled by a murderous enfilading fire directed from the rooftops and gardens of Solferino, as well as a steady peppering from the Austrian Jäger battalions hidden among the bushes and trees that covered the approaches. Forey ( I Corps) had committed both of his brigades in support of Ladmirault’s attack, while further to the right Bazaine division was heavily engaged in assaulting the cemetery. Seeing that no progress was being made on either flank, and that a decision could only be achieved in the centre by breaking the Austrian hold on Solferino, Napoleon ordered forward Camou’s division of the Imperial Guard. This fresh injection of force finally tipped the scales in favour of the French and the Monte di Cyprées was taken by storm. During this bloody action a bullet fractured General Ladmirault’s left shoulder and after having the wound dressed and returning to the fighting line he was unlucky enough to receive another bullet wound in the leg. General Dieu, commanding the Imperial Guard Voltigeurs had fallen at the head of his men; Brigadier General Auger leading one of Forey’s brigades had his arm mangled by shrapnel but refused to leave the field and Forey himself took a bullet in the hip from a hail of fire that killed two of his ADCs, one of whom, Captain de Kervenoel had the top of his head removed by an artillery shell. [31]Turnbull. Patrick, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation, page 135 The plain and hillsides were covered with dead and wounded, the latter not only suffering from terrible injuries but also from exposure to the boiling sun and lack of water.

Austrians and allies trampled one another under foot, slaughtered each other on a carpet of bloody corpses, smashed each other with rifle butts, crushed each other’s skulls, disembowelled each other with sabre and bayonet.

It was butchery; a battle between wild beasts maddened and drunk with blood. Even the wounded fought to the last breath. [32]Dunant. Henri, A Memory of Solferino, page 9

(Mary Evans Picture Library)

With the capture of the Mont di Cyprées the French now began to reorganize for an assault on Solferino village. Here every house had been turned into a stronghold, well barricaded and staunchly held. The San Pietro cemetery, defended by two Croatian battalions, was a veritable redoubt, which had withstood the pounding of French artillery and repeated assaults by massed infantry for four hours.

While the battle for Solferino was in progress General Niel’s IV Corps to the south had managed to contain the uncoordinated attacks sent in by Schwartzenberg and Schaffgotsche and was about to mount his own offensive against Cavriana. But at 11 a.m. fresh Austrian masses were arriving in form of Weigl’s 11th Corps. Fortunately MacMahone had been able to come into line on Niel’s left from where he directed the divisions of La Motterouge and Decaen to march on Solferino, positioning the cavalry of the Imperial Guard, which had been placed at his disposal, to cover his right. At the same time Canrobert sent one of Trochu’s brigades to bolster Niel’s line, holding the other brigade around Medole. Bourbaki’s division was grouped around Castel Goffredo protecting his flank from the south and southeast. [33]Wylly. H.C. The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino, page 147-148

Back at the centre, and after great exertions, the French finally took Solferino at around 1.00 p.m. The fighting here had been severe with houses changing hands several times as attack was followed by bloody counter attack. Five times the French Foreign Legion regiments of Castagny’s brigade (II Corps) fought their way into the San Pietro cemetery, only to be evicted by its Croatian defenders; finally the sweat soaked and blood caked Legionnaires captured the place, bayoneting the defenders in a perfect fit of madness and hatred that left more corpses above ground in the cemetery then were buried below.

With the capture of Solferino the French now turned their attention to the Cavriana heights. Leaving Ladmirault’s battered division to hold Solferino village, Napoleon ordered Bazaine’s division to keep after Stadion’s retiring Austrians, who had pulled back towards Pozzolengo, while Forey’s division and the Guard attacked Cavriana. At the same time MacMahone attacked Cassiano, which he gained after a brief but costly struggle, and then proceeded to assault Monte Fontana, driving back two full brigades of the Austrian 7th Corps, and bringing artillery onto the heights. It was now just after 2.00 p.m. and noticing that the Imperial Guard had not yet come into line between his corps and that of Niel’s, and also that the Austrians were preparing a counter attack, MacMahone decided that rather than pushing on he would consolidate his position. This proved to be a sound decision as the two Austrian brigades, now regrouped, came forward in a desperate attempt to regain the hill, and only with the arrival of a brigade of the Guard together with the advance of his whole corps did MacMahone manage to drive the enemy back to Cavarina. [34]Wylly. H.C, The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 148

The Cavriana Ridge would also prove a tough nut to crack. Here once again the Austrians had fortified every house and barn, cramming troops into and around the village in slit trenches and behind hastily constructed stone and timber breastworks. Noting the situation Napoleon decided that before any assault by the infantry he would soften up the defenders with artillery fire, and to this end he ordered the Guard artillery to carpet the place with cannon fire. The effect on the defenders proved devastating. In the crowded conditions that prevailed in and around the village every shot and shell from the French guns, even if they did not strike the enemy directly, caused casualties from showers of stones and jagged splinters of wood that flew through the air in all directions. Walls collapsed and the roofs of buildings caved in reducing the whole village to rubble with clouds of thick dust and smoke blotting out the sun. Small wonder then that when the French infantry advanced they were met by little resistance, while the Austrians fell back in great disorder, some units even bolting back as far as the Mincio bridges. [35]Turnbull. Patrick, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation, page 139

To the south Niel’s IV Corps, now supported by over forty guns, still showed a bold front despite repeated, if uncoordinated attacks, and he even attempted a forward movement himself sending troops to assault Guidizzolo; however, the village was held in considerable strength, which caused the attacking French columns to fall back on the hamlet of Baite. By 3.00 p.m. Canrobert had begun to shift his corps from its covering position on the right, moving Bourbaki’s division from around Castel Goffredo to link up with Niel’s left. Bataille’s brigade of Trochu’s division also moved forward to attack Guidizzolo. On the Austrian side Count Wimpffen’s First Army had previously received orders from Franz Joseph to try and strike at the French centre thus taking some of the pressure off Solferino, but with the 3rd and 9th Corps fully committed to containing the Niel and Canrobert, and most of the 11th Corps, together with his cavalry division, used up in penny packets to strengthen weak points in his line. What few reserves were at hand Wimpffen pushed out from Guidizzolo in a futile attempt to meet with his master’s orders. These proved too few and too late as they were soon halted by the French Imperial Guard cavalry, which had moved to cover the ground between MacMahone’s right and Niel’s left flanks. Seeing the Austrian advance stalled, Bataille’s brigade now redoubled its attack on Guidizzolo, and although their élan forced the Austrians to give ground they still failed to capture the town. [36]Wylly. H.C, The Campaign of Magenta and Solferion 1859, page 149

(Heeresgeschichtliches Museum Vienna)

Away to the north Benedek had little trouble holding his position against the Piedmontese divisions of Cucchiari and Mollard, and had given them such a warm reception that by 11.00 a.m. the fighting on his front had died down. Things started to stir again at around 2.00 p.m. when Victor Emmanuel once more regrouped his divisions to assault the Austrian position. At the same time Benedek received orders from Count Schlick to make a diversionary attack against the French left, and still another request from Franz Joseph’s headquarters to send troops to help with the defence of Solferino. Noting the fact that he would in all probability have to contend with far greater pressure than had been thus far forthcoming, and seeing the deployment of the Italian forces in greater numbers, Benedek demurred on both counts of giving assistance. His judgement was soundly based on the fact that to be of any help he would have to detach at least two of his brigades, and in the face of the gathering masses on his front this depletion of strength would compromise his position as well as that of the whole Second Army should he be forced back uncovering Pozzolengo and that armies line of retreat. [37] Ibid, page 150

At 3.00 p.m. Benedek received news of the retreat of the 4th Corps from Solferino and pulled four battalions out from his main line sending them to occupy the high ground to the south and south-west of Pozzolengo, covering the his left flank and endeavouring to keep in contact with the 4th Corps. These troops had scarcely reached their destination when they were vigorously attacked by a brigade from Fanti’s 2nd Division, which had moved to support Durando’s 3rd Division now coming into action towards Madonna della Scoperta. At the same time Mollard began to advance on San Martino, while Cucchiari’s 5th Division also moved to attack San Martino from the direction of Rivoltella and San Zeno.

August Ludwig Ritter von Benedek (Heeresgeschichtliches Museum Vienna)

Fortunately for Benedek the Piedmontese failed once more to coordinate their attacks, with neither Mollard nor Cucchiari being unable to agree on whom should take overall command, and neither general bothering to ask headquarters to obtain a ruling on the matter. Also the fact that no staff officer was at hand from headquarters to settle the issue meant that both generals “did there own thing” with no synchronized effort being made, and as a result each assault was beaten back with great loss. To cap it all Cucchiari, without any consultation with Mollard, pulled his entire division back to Rivoltella, leaving the latter isolated and the artillery uncovered. [38]Turnbull. Patrick, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation, page 142

Maybe Benedek should now have gone over to the offensive, but given the state of the rest of the Austrian forces, plus the fatigue of his own troops after hours of fighting under a scorching sun, then perhaps he did the correct thing in just holding his ground. After all he had given the Italian army a very bloody nose, and his own casualties were light in comparison and it does take a very daring commander to abandon a sound defensive position and go over to the attack, especially when the back door may have been left open.

When told of the withdrawal of Cucchiari’s division, Victor Emmanuel flew into a rage, ordering General Marmora, his lacklustre second in command, to mass four divisions for a final assault on San Martino stating, ‘a qualunque costa la posizione al nemico’ (‘ the position must be taken from the enemy no matter what it costs’) [39]Quoted in, Turnbull. Patrick, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation, page 144 If such a concentration of force had been properly organised then in all probability the Austrians would have been overwhelmed, as it happened Marmora detached one division for a diversionary attack on Pozzolengo, thus reducing the hitting power of his assault which resulted in yet another failure, the Piedmontese being repulsed in short order by the steady defensive fire of the Austrians. [40]Ibid, page 144

Towards 5.00 p.m. , just as the Italian divisions were recoiling from their unsuccessful assault on San Martino a great thunderstorm burst over the battlefield. Massive dark clouds had been gathering for some time, and now the heavens opened with such a downpour that all operations came to a standstill for almost an hour. This fortuitous event enabled the Austrian Second Army to continue their retirement in an orderly fashion towards the Mincio River crossings.

Wimpffen’s First Army had also begun to retire. With no support forthcoming, and his reserves long since used up, Wimpffen informed Franz Joseph that he could no longer maintain his ground. He therefore ordered the 9th Corps to fall back towards Goito, while the 3rd Corps retired by way of Cerlungo to Ferri. 11th Corp covered the retreat of the other two, eventually moving back towards Goito, and then Roverbella. The Austrian Emperor himself had still harboured the vision of counter attacking Solferino until late in the day, but upon receiving the news of the First Army’s plight he realised that any hope of saving the battle was gone. Ordering a full withdrawal behind the Mincio River, Franz Joseph instructed Schlick to place a strong retaining force between Cavriana and Volta to cover the retreat of the other corps.

The last Austrian troops to leave the battlefield were Benedek’s 8th Corps. As the rain subsided the battle on his front sprang back to life. But the Italian attacks put in by Fanti and Mollard were easily repulsed causing both divisions to fall back in some disorder towards Lake Garda. For the first time that day Benedek felt confident of doing some serious damage to the Piedmontese army, and after a successful attack which dislodged General Durando’s division from around Modonna della Scoperta he was now ready to advance his whole corps against what appeared to be a rapidly deteriorating enemy. However he now received orders from Franz Josef to fall back towards the Mincio, covering the retreat of Stadion’s and Clam-Gallas’s corps. These orders were carried out with the utmost punctuality and discipline, and it was well past midnight when, after making sure that no pursuit was forthcoming, he finally crossed over the river himself. For his part in this great battle the soldiers coined a phrase, still remembered today, “Benedek’s Glory.”

The French and Piedmontese were in no shape to follow up their victory. Battle fatigue, heat and thirsts, as well as the enormous task of dealing with the wounded dictated that no pursuit of the enemy was forthcoming, and the Austrians were able to regain their position on the left bank of the Mincio River, from where, on the 25th June, they continued their retreat to the Adige.

Losses had been substantial on both sides. The French and Peidmontese together suffering over 17,000 killed, wounded and missing, and the Austrians over 20,000. General officer casualties were also high with the French having five wounded, the Italians two, and the Austrians four. Regimental and battalion officers were also badly hit, the French losing 117 killed and 644 wounded, the Austrians over 600, and the Italians a similar number. The whole countryside for miles around the battlefield was littered with the dead and wounded, of which many of the latter soon succumbed to their wounds owing to the appalling lack of care which, as mentioned in the introduction, caused Henri Dunant to form the Red Cross in an attempt to alleviate the suffering of the wounded [41]Although having the greatest respect for what he achieved, I feel that when reading Dunant’s account of the battle in, ‘A Memory of Solferino,’ one should treat his narrative with care. A lone … Continue reading. *

Not having achieved the crushing victory he had hoped for, and threatened by Prussian mobilization, Napoleon III decided to put an end to hostilities as quickly as possible. Therefore, without consulting Victor Emmanuel, on the 11th July 1859 the French and Austrian emperors concluded the Treaty of Villafranca in which Austria ceded Lombardy over to the French, who then turned it over to Victor Emmanuel, while Tuscany and Modena were restored to their former dukes. None of this went down well with the Italians, who considered themselves betrayed, and the animosity would continue to affect the relationship between France and Italy until the end of the Second Empire in 1870.

Solferino Today

Even if you have no interest in battles and battlefields (there are several in the area) then a visit to Solferino is still well worth undertaking. The village itself is a peaceful place to spend a morning just strolling around, and it has many shaded walks winding around the tower of the “Spy of Italy” and the Mount of Cypress. We found a very nice little café for lunch, with some ice – cold beer to help cool us down after our battlefield ramblings.

The small museum inside the “Spy of Italy” displays uniforms and weapons from the battle, as well as a black and white panorama photograph of the battlefield taken at around 1900. The assent and descent of the tower itself is made easy by having a shallow walkway spiralling upwards to the top, which make it easy on the legs and allows more time to view the various battle paintings that adorned the side of the building, and the view from the top…well, see the panorama photographs enclosed!

The Mount of Cypress is a very moving experience, with its many nationalities memorial plaques and its flapping pennants, as if they were waving farewell to the passing souls of those who gave their lives in the great battle. Do take time to visit this spot, you will not be disappointed.

The Museo Risorgimentale just on the outskirts of the village has a wealth of weapons and uniforms from the battle, as well as examples of Austrian, French and Piedmont cannon; some fine prints and posters are available at the information desk.

When leaving the museum one should take the road uphill towards the Ossuary Chapel which is located in the Church of St.Pietro in Vincoli. Outside there are various busts of Marshals of France and one of Napoleon III himself, but inside be prepared for a surprise. Every wall from floor to ceiling is stacked high with the bones and skulls of the dead gathered and interned here some years after the battle, so that they could have a decent resting place rather than be scattered in unmarked graves across the landscape. Remember this was in the days before the Great War of 1914-1918, which so shocked the world that the war graves commission was set up to give the dead a permanent and peaceful place to rest- the Ossuary was the precursor of these modern war cemeteries. It is quite a queer feeling being stared down at from so many empty eye sockets!

For those interested there is a hotel in Solferino, “Hotel Albergo” La Spia D, Italia. One can also rent a farmhouse at “Le Sorgive,” near the village, although I do not know what the cost would be.

At Cavrina there are the remains of an old fortress, as well the Alto Mantovano Museum of Archaeology, while at Mazambano the castle should be worth a visit. I have also been informed that Cavriana also has a Festival and Fair each January and February when local delicacies like salami and wild mushroom risotto are served, together with some fine wine from the Colli Morenici del Garda.

For more spectacular views of the battlefield or just the green and rolling landscape plus Lake Garda, framed by the mountains in the distance, then the tower of San Martino should be on your itinerary. Like the “Spy of Italy” it has a spiralling walkway to the top, which makes the climb a whole lot more pleasant.

Click HERE for an interactive panorama taken from the top of the tower.

During our visit in May 2007 we stayed at the Hotel Piroscafo in the centre of Desenzano (http://www.hotelpiroscafo.it/). This is a nice town slap bang on the shores of Lake Garda. It has very good shops and pleasant winding streets, which play host to the vintage and veteran cars that take part in the Mille Miglia rally every May.

Desenzano castle is perched high on the hill overlooking the town and the lake, and the alleyways and small back roads running up to it have some splendid little bars and restaurants hidden away around each corner. The only thing to be aware of is the fact that half the population of Milan seems to descend on the town each week end, many thousands of whom seem to ride motor cycles.

The town offers fine food and wine with just the right amount of “rustic” charm that sets it apart from the every day tourist attraction. Give it a go; we intend to return in 2008 to visit the battlefield of Rivoli so watch this space!

References

| ↑1 | The dukes of Savoy became kings of Sardinia in 1720; thereafter they acquired Piedmont in 1748. A central government was set up in Turin. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gooch. G.P, The Second Empire, page 21 |

| ↑3 | McElwee. William, The Art of War, page 34 |

| ↑4 | Ibid, page 36 |

| ↑5 | Nosworthy. Brent, The Bloody Crucible of Battle, page 53-54 |

| ↑6 | Ibid, page 57 |

| ↑7 | Ibid, page 397-398 |

| ↑8 | Quoted in, Nosworthy. Brent, The Bloody Crucible of Courage, page 59 |

| ↑9 | Nosworthy. Brent, The Bloody Crucible of Courage, page 282 |

| ↑10 | Ibid, page 74 |

| ↑11 | McElwee. William, The Art of War, page 51 |

| ↑12 | Craig. Gordon .A, The Battle of Königgrätz, page 25 |

| ↑13 | Craig. Gordon. A, The Battle of Königgrätz, page 22 |

| ↑14 | Engles. Frederick, The Armies of Europe, page 8 |

| ↑15 | Engles. Frederick, The Armies of Europe, page 7 |

| ↑16 | Brooks. Richard, The Austro-Sardinian War, The History Net |

| ↑17 | McElwee. William, The Art f War, page 40-41 |

| ↑18 | 1911 encyclopedia.org/Itailan Wars |

| ↑19 | Turnbull. Patrick, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation, page 120. Turnbull mentions concealed and well-sighted gun positions but makes no mention of range markers. (Authors note) |

| ↑20 | Sociéta Solferino e San Martino, pamphlet, San Martino della Battaglia Museum. |

| ↑21 | Meglegnano website. |

| ↑22 | Wylly. H.C, The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 133-134 |

| ↑23 | Turnbull. Patrick, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation, page 124 |

| ↑24 | Wylly. H.C., The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 131- 132. |

| ↑25 | I am grateful to Roger Brugge who supplied the weather details for 1859. |

| ↑26 | Wylly. H.C. , The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 141 |

| ↑27 | Wylly. H.C., The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 142. |

| ↑28 | Wylly. H.C., The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 144. |

| ↑29 | Ibid, page 144. From a poem written in his honour in 1849 |

| ↑30 | Wylly. H.C., The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 146 |

| ↑31 | Turnbull. Patrick, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation, page 135 |

| ↑32 | Dunant. Henri, A Memory of Solferino, page 9 |

| ↑33 | Wylly. H.C. The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino, page 147-148 |

| ↑34 | Wylly. H.C, The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino 1859, page 148 |

| ↑35 | Turnbull. Patrick, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation, page 139 |

| ↑36 | Wylly. H.C, The Campaign of Magenta and Solferion 1859, page 149 |

| ↑37 | Ibid, page 150 |

| ↑38 | Turnbull. Patrick, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation, page 142 |

| ↑39 | Quoted in, Turnbull. Patrick, Solferino: The Birth of a Nation, page 144 |

| ↑40 | Ibid, page 144 |

| ↑41 | Although having the greatest respect for what he achieved, I feel that when reading Dunant’s account of the battle in, ‘A Memory of Solferino,’ one should treat his narrative with care. A lone civilian out at the battlefront could not have witnessed his descriptions of the close-up fighting, and even if he did manage to attach himself to one of the corps or divisional staffs he could still not have been everywhere or seen everything he describes. Being in the town of Castiglione della Pieva while the battle was being fought probably enabled him to interview officers and men returning from the front, and the plight of the wounded, as well as the state of the battlefield over the following days most certainly had a dramatic effect upon him personally. |