July 1st-3rd 1863.

Pickett’s Charge, July 1st-3rd 1863.

Military history always seems to favour the underdog more so than the victor. The Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava, Custer’s Last Stand at Little Big Horn, Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo are all studied avidly by those who consider that if this or that had been different these defeats and blunders would have in some way changed the course of a campaign or battle. So it is with Pickett’s Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg, on that hot summer afternoon of July 3rd 1863. The controversy that arose after the battle, and the subsequent debate and claims that have continued down the years since have done more for the name of George Pickett than he ever gained in real military terms. The sad thing is that Pickett should be remembered for a glorious failure for which he was in no way responsible, or for that matter had the slightest idea that his name would be associated with leading.

Born in Virginia in 1825, George Edward Pickett graduated from West Point (class of 1846) at the bottom of a class of 59 other graduates. He was commissioned into the infantry and won a brevet (entitling an officer to take rank above that for which he receives pay) in the Mexican War for his part in the storming of Chapultepec (13th September 1847). He fought against Indians on the frontier, and was commended by the American government for his part in defying a British squadron off San Juan Island in Puget Sound. Resigning as Captain on 25th June 1861, Pickett was then commissioned Colonel in the Confederate States Army. He rose to the rank of Brigadier General in 1862, and was wounded at the Battle of Gaines Mill (27th June 1862). Promoted to Major General in October 1862 he commanded the centre of the Confederate line at the Battle of Fredericksburg (13th December 1862) but saw little action. After Gettysburg he was made department commander of Virginia and North Carolina. He failed in his attack on New Bern in January 1864 but took an active role against Union General Ben Butler at Drewry’s Bluff (4th-16th May 1864). He commanded at Five Forks (1st April 1865), and surrendered with General Longstreet at Appomattox Court House on the 9th April 1865. [1]The above information was taken from, Cassell’s Biographical Dictionary of the American Civil War 1861-1865. Mark M.Boatner III Editor. Page.651

Lee’s Plan of Campaign.

(Library of Congress)

After his brilliant defeat of the Union army at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, General Robert E. Lee decided upon a fresh invasion of the North, where it was believed that a decisive victory would not only encourage the peace movement in the North in their favour, but also cause England to intercede on behalf of the Confederacy. As well as these factors, a campaign outside of the wasted countryside of Virginia would mean that Lee’s army could sustain itself at the enemy’s expense, always a favourable proposition for an invading army. It was also hoped that the invasion would take the pressure off the Western Theatre of war by causing the Federals to move troops from around Vicksburg and Chattanooga to meet the threat.

The Army of Northern Virginia that fought at Gettysburg numbered some 75,000 men, including cavalry and artillery and was, arguably, the finest fighting force ever raised on American soil up to that time. The death of General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson had been a great loss to both the army and to General Lee, its commander, who now reorganized it into a three corps system. The reason for this was that Lee considered that the existing two corps, of some 30,000 plus men each, was too large for one general to handle, stating that the wooded country where the troops had recently seen action was, “always beyond the range of his vision, and frequently beyond his reach.” [2]Edwin B.Coddington. The Battle of Gettysburg, A Study in Command. Page 11. Also a shortage of good officers had caused Lee much concern in previous campaigns, but now he was forced by circumstances to appoint two new lieutenant generals, each commanding an army corps. The First Corps remained firmly in the hands of Lieutenant General James (“Pete”) Longstreet, its original commander. The Second Corps went to Lieutenant General Richard S. (“Baldy”) Ewell, this had been Jackson’s old corps, while the Third Corps, which had been raised by taking a division each from the other two, and raising a new one, was commanded by Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill. [3]Ibid, page. 12.

Pickett’s Division.

It was Longstreet’s corps that contained Pickett’s division, and although the two generals were good friends, Pickett had not yet led his division in combat. Its composition was as follows.

| First Brigade. Brigadier General Richard B.Garnett. |

|

|---|---|

| 8th Virginia Regiment, Colonel Eppa Hunton. | |

| 18th Virginia Regiment, Lieut-Colonel H.A.Carrington. | |

| 19th Virginia Regiment, Colonel Henry Gantt. | |

| 28th Virginia Regiment, Colonel R.C. Allen. | |

| 56th Virginia Regiment, Colonel W.D. Stuart. | |

| Second Brigade. Brigadier General Lewis A. Arminsted. |

|

|---|---|

| 9th Virginia Regiment, Major John Owens. | |

| 14th Virginia Regiment, Colonel James G.Hodges. | |

| 38th Virginia Regiment, Colonel E.C.Edmonds. | |

| 53rd Virginia Regiment, Colonel W.R. Aylett. | |

| 57th Virginia Regiment, Colonel John Bowie Magruder. | |

| Third Brigade. Brigadier General James L.Kemper. |

|

|---|---|

| 1st Virginia Regiment, Colonel Lewis B. Williams | |

| 3rd Virginia Regiment, Colonel Joseph Mayo, Jr. | |

| 7th Virginia Regiment, Colonel W.T.Patton. | |

| 11th Virginia Regiment, Major Kirkwood Otey. | |

| 24th Virginia Regiment, Colonel William R.Terry. [4]Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Vol, III, page. 437-438. | |

Two other brigades belonged to Pickett’s division but these were detached for duty elsewhere thus reducing his command to some 5,700 men, including his divisional artillery under Major James Dearing of 18 guns.

Opening Moves

James Longstreet

(Library of Congress)

From his correspondence it would appear that Longstreet was fully in favour of another invasion of Northern soil, stating that, “We should make a great effort against the Yankees this summer…every available man and means should be brought to bear against them…” [5]Edwin B.Coddington, The Battle of Gettysburg, A Study in Command. Page, 11 No mention is made of any defensive attitude to be adopted, or any word of caution concerning the probability of a Union counter offensive. Longstreet, despite his post war claims that he had urged Lee to consider “defensive tactics”, and that he had received a “promise” from Lee to this effect, would seem to have been in complete harmony with his commanding general’s plans. [6]See James Longstreet, “Lee in Pennsylvania,” Annals, 417. Also his account of, Lee’s Invasion of Pennsylvania,” Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol.III, page, 245-247. The subject is … Continue reading

Leaving A.P.Hill’s Third corps to guard his rear, Lee concentrated the First and Second corps around Culpeper on 8th June. Thereafter the Union commander, “Fighting Joe” Hooker, instigated a series of reconnaissance operations, which brought on the engagements at Franklin’s Crossing (5th June) and Brandy Station (9th June), both of which alerted Lee to the fact that Hooker could be intending a move against Richmond. In case of this event Lee ordered Ewell’s Second corps to destroy the Union garrison in the Shenandoah Valley which would cause the authorities in Washington to move Hooker back in order to cover the capitol. On 25th June Lee’s army was crossing the Potomac River, but did not know that Hooker had been shadowing him on his eastern flank. The problem for Lee was that he had allowed General J.E.B.Stuart’s cavalry, “the eyes of his army”, to go dashing off around the Union Army on one of his raids. It was at this stage of the campaign that President Abraham Lincoln, who had lost his faith in Hooker’s ability to command the Union forces, replaced him, on the 28th June with Major General George Mead. The Union Army of the Potomac numbered over 100,000 men.

Lee now decided to recall Ewell’s corps, and with his army united between Cashtown and Gettysburg he sought to threaten Washington, Philadelphia or Baltimore. By so doing he hoped to encourage Mead to attack.

On the morning of 28th June, Ewell was ordered to cross the Susquehanna River and take the town of Harrisburg while the other two corps moved to join him. Mead also moved towards Harrisburg in an attempt to threaten Lee’s communications, which would still allow the Union army to cover Washington. Also Mead had reconnoitred a strong defensive position at Pipe Creek, about fifteen miles southeast of Gettysburg where he hoped Lee would try to attack. It will be seen from this that both commanding generals were not anxious to be the aggressor until such time as the strategic picture became clearer, and it was possible that Mead never even contemplated any offensive operations after what he had seen at the battle of Fredericksburg the previous winter. He was quite content to cover Washington and let the Confederates come at him. The encounter at Gettysburg on 1st July therefore was neither planned nor expected by either side, but like most encounter battles it gradually sucked in both armies until neither side was left with any alternative other than to see it through to the end.

The opportunity of victory? Day One.

The story goes that Confederate Major General Henry Heth, commanding a division in A.P.Hill’s corps, ordered one of his brigades to go into Gettysburg to search for supplies, as it was thought that a large store of shoes had been deposited in the town. This either shows great naivety on Heth’s part, as the town had already been passed through by the Confederate division of General Jubal A. Early, or, and this is the more probable explanation, that Heth was just spoiling for a fight. To send a full brigade, without a cavalry escort to procure shoes without knowing the location of the enemy is certainly not the action of a professional field officer. As it turned out the brigade commander, Brigadier General James Johnston Pettigrew stumbled upon the Union troops in Gettysburg, and managed to pull back without bringing on a general engagement. [7]Edwin B.Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command, page 263However, Heth and Hill considered that their chances of brushing aside what elements of the Union army that had thus far arrived in the town better than average, and ordered their men forward.

The troops that Pettigrew had met belonged to the cavalry division of Major General John Buford who was reconnoitring ahead of the Union army. Buford immediately saw the importance of holding Gettysburg as it formed the centre of a network of roads, which converged at this point. At around 8.00 am on the morning of 1st July elements of Heth’s division drove-in the Buford’s picket line and soon a very sharp action began to develop which escalated into a full blown battle as more troops from each side came on the field. By 10.30 am the Confederates had established a strong position on McPherson Ridge, about a mile northwest of Gettysburg, while the Union forces formed a straggling defensive line about 600 yards to the east on Seminary Ridge. The fighting became fierce as A.P. Hill now came up with more of his corps, which he threw into the fray, and Ewell’s Second Confederate corps also began to debouche from the northeast. Heth was wounded, and one of his brigade commanders, Brigadier General James J. Archer was captured. On the Union side, Major General John Fulton Reynolds commanding the I Corps had been killed by a sharpshooter early in the battle, and two divisions of Major General Oliver Otis Howard’s XI Corps, which had come up to support Reynolds right flank were driven back through Gettysburg in disorder, but managed to reform on its reserve division on Cemetery Hill south of the town. Owing to this the Union I Corps also fell back to a defensive position on Cemetery Hill.

When Lee finally arrived in the afternoon he was confronted by the fact that he now had a battle on his hands which he had not intended, but that the results thus far, and the commitment made, caused him to tip his hand and go for a full blown attempt to sweep the Union forces from the field. To this end he ordered Ewell to attack the Union position, but phrased his orders in such a way that they included the expression, ‘if practical.’ [8]Ibid, page. 315 This was enough for Ewell to decide that such an undertaking was not possible at this time. Not only this, but Lee had made it clear that no help could be expected from Hills corps, owing to the shattered state of some of its brigades and regiments. Whether Lee had consulted Hill in regard to giving Ewell assistance, or if Hill himself had made it clear to Lee that his corps was in no condition to combine in the attack is unclear. What does emerge is the fact that Lee’s vague orders and his corps commanders interpretation of them were to cause even greater misunderstandings during Pickett’s advance on the 3rd July. Could Ewell’s corps have pushed the Union forces off Cemetery Hill without assistance from other Confederate troops? Possibly not. When we allow for the fact that Ewell’s troops had lost their impetus, and not only had to re-group, but also look after thousands of captured Union prisoners who had been taken during their confused retreat through the town, then the idea of a successful attack before dark seems highly improbable.

Meanwhile, reinforcements were coming up to bolster the Union position and by 6.00 pm more than 20,000 troops were holding a line from Culps Hill, northwest of Cemetery Hill, continuing around the latter and spreading south along Cemetery Ridge as far as the Little and Big Round Top’s which marked the limit of their left flank. By 8.00 pm their numbers had increased to 27,000 with 85 cannon, and more were on the way. These were enough to hold against any offensive actions on the part of the Confederates until the rest of the Union army reached the field.

Though inwardly he may have been disappointed at not being able to press home the advantages gained on this first day of the battle, Lee now sought a way of capitalising on the undoubted success his troops had thus far gained. While meditating on this matter from his position on Seminary Ridge, he was joined at about 5.00 pm by General Longstreet who had rode forward ahead of his corps to discuss the situation with his chief. It was during their discourse that Longstreet suggested a turning movement around the Union left flank, however he never made it clear if this was to be a tactical or a strategic movement. What he did state was that he considered a direct attack on the Union position should be avoided. It was, after all Longstreet’s corps that had held the sunken lane at Fredericksburg the previous December, and he was well aware of what determined troops could do to any attacking columns when properly entrenched and covered by massed artillery.

Lee thought about alternatives and finally decided that he could not justify a flanking movement. He would hit the enemy where they stood, and hit them hard. With his boys geared-up for another victory he saw no reason to cool their enthusiasm by more marching which would, in all probability only result in the Union forces conforming to his movements and taking up an even stronger defensive position than the one they now occupied. This seems to have liberated a growing depression in Longstreet’s mind, which would cause him to become, if not complacent, then certainly only half hatred in his attitude towards carrying out Lee’s orders, and once again this would result in serious repercussions on day three of the battle.

Having made up his mind to remain on the offensive, Lee now consulted his other corps commanders to discuss a plan of action for the next day. It was eventually decided that Longstreet’s corps (less Pickett’s division which was still some miles from the battlefield) would assault the southern end of Cemetery Ridge, there axis of advance would be northeast towards the Emmitsburg Road which Lee considered would bring them down directly on the Union left flank causing their whole line to be rolled up. As soon as he heard Longstreet’s guns announce the commencement of this attack, Ewell’s II Corps would make a strong demonstration against the Union right. Hill’s corps would also open with its guns on the Union centre, and in so doing add to the uncertainty of just where the real blow was about to fall.

Almost, but not quite. Day Two.

As can be seen from the above, Lee’s plan called for very close cooperation and coordination by all three of his corps. Unfortunately for Lee, and the Army of Northern Virginia, this was not forthcoming. Instead of the morning attack that Lee was anticipating, Longstreet dawdled in moving his troops into position and wasted precious hours marching and counter- marching his divisions to their attacking stations. During this period Mead, who had arrived on the field at midnight, was given time to deploy more troops along Cemetery Ridge. He now had XII, II and III Corps in line with the I and XI, while the V and VI were rapidly approaching. The problem with Mead’s position was that his III Corps commander, Major General Daniel Sickles had taken it upon himself to advance half a mile west of the main Union line, creating a dangerous salient.

It was not until well after 4.00 pm in the afternoon that Longstreet finally began his attack, a truly inordinate amount of time for a corps commander to take in moving troops only a few miles further along Seminary Ridge. He was also not keen to start the attack without Pickett’s division, and told Major General John Bell Hood, one of his other division commanders that he, “ never liked the idea of going into battle with one boot off.” [9]Ibid, page, 377 Finally Longstreet managed to get the attack going, and for three hours both sides were involved in some of the bitterest fighting of the Civil War, well remembered today for such places as, The Wheat Field, The Peach Orchard and Devil’s Den. Sickles isolated III Corps was eventually pushed back, and the Confederates even managed to get troops around and up the sides of the Round Top’s. Here, however, the attack stalled. Thanks to the prompt action of Brigadier General Gouverneur K.Warren who was with his signal station on Little Round Top. Frantic messages were sent to warn of the impending attack, while Warren himself dashed off to find troops to stem the Rebel advance. [10]For an account of this stage of the battle see Brevet Major General Henry J.Hunt’s description in, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol III, page, 290. Also a very detailed description is … Continue reading Colonel Vincent Strong, commanding a brigade in the First Division of the V Corps rushed his men to the hill, with Colonel Joshua Chamberlain’s 20th Maine Regiment in the lead. The Union line stopped the Rebel advance on the rock and wood covered summit of the Little Round Top, and after a particularly fierce struggle they forced the Confederates back down the hill. To add to their discomfort the Rebels were now assailed by two guns from Hazlett’s Union battery, which had been manhandled up the slope and these, together with the fire from other regiments, including the redoubtable 140th New York, enabled the hill to be secured.

Despite their chief’s dilatory behaviour, Longsteet’s troops, together with three brigades from Hill’s corps, had almost succeeded in breaking the Union line that was held by close on six full divisions, plus elements from other brigades. The unfortunate part of it was that these events only fuelled Lee’s belief in the fact that his boys could do anything. As Longstreet’s attack was going in, Ewell’s artillery began to thunder over on the left in preparation for the attack on Culps Hill and Cemetery Hill.

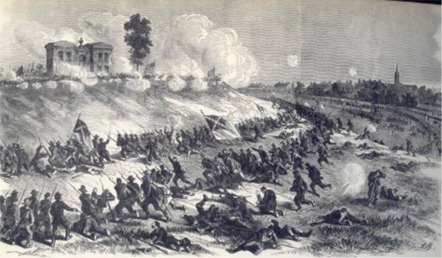

Contrary to popular belief, the Confederate attack on this part of the field was not, at least to the men of Ewell’s corps, a diversionary affair. The struggle here became sanguine in the extreme. Amid the boulder strewn slopes and the dense cluster of trees on Culps Hill the blue and grey troops became embroiled in a desperate seesaw battle that the Union forces just managed to contain, although they had to forfeit part of their forward entrenchments to the Rebel division under Major General Edward “Allegheny ” Johnson. On their right yet another surging attack was made by the Confederates of Major General Jubal A.Early’s division against Cemetery Hill. Early’s men crossed three lines of Union rifle pits and a stonewall routing part of Howard’s XI Corps in the process, but were eventually forced to retire, the battle sputtering to an end at around 10.00 pm amidst the cries and groans of the wounded.

A Drawing by the war artist Edwin Forbes, supposedly made at the time. It shows the attack of Ewell’s corps on Cemetery Hill during the evening of 2nd July. (Culver Pictures, New York)

The fighting on the 2nd July had cost both sides a combined total of over 16,000 men and had done nothing except convince Lee that one final push on the following day would bring him victory, however the real lesson behind all this blood-letting seems to have been overlooked by the Confederate commander. Although the Union army had been rocked on its heels by the blows delivered, it had not been broken. Its resilience and morale was undamaged, and, if anything, it was even more prepared after the events of the previous two days fighting to hold its ground and let the Rebels bite on granite. At a council of war held by General Mead at 9.00 pm that night it was decided that, even allowing for the problems of supplies, which the Union army had outrun in their rapid advance to Gettysburg, the army would hold fast on the defensive for another day. Thus, like two schoolboys trying to outstare each other, Mead had defiantly decided that he was not going to be the one who blinked first. If Lee had been able to walk amongst the Union ranks on that fateful dawn of the third day, he may have at last understood that the attitude of these troops, and their commanding generals had changed since the days of the slow moving George Brinton McClellan, and the wavering “Fighting Joe” Hooker. Because his previous victories had been brilliant, the glare dazzled Lee into thinking that whatever he asked of his men they were capable of doing. By adopting this attitude, he not only completely underestimated his enemy (a bad thing to do for any commander), but was also prepared to waste the precious manpower and resources that neither he nor the Confederacy could afford.

Hope, Doubt and Failure. Day Three.

With the return of Stuart’s cavalry Lee, now more determined than ever to force a decision, devised a plan that would follow the same basic pattern set on the previous day. Ewell would conduct a diversionary attack against the Union left flank, while Longstreet, now with Pickett’s fresh division on the field, would use it in conjunction with divisions from A.P.Hill’s Corps to smash through the Union centre, and Stuart would then be in position to move around to the left and disrupt the enemy’s line of retreat.

For some unaccountable reason, Lee never sent orders to either Pickett or Longstreet stating his intention to begin the assault at daybreak, although he did manage to send one to Ewell. Consequently, precious time was lost in grouping the various elements of each division and brigade into the correct positions for the assault. It has been suggested that Lee was biding his time in order to discuss the overall situation with Longstreet, who he had selected to lead the attack. [11]See, Shelby Foote, The Civil War, A Narrative, Vol II, page, 526 Whatever his reasons, Lee went in search of the man he fondly christened, “My War Horse” to gauge his feelings. If he expected overwhelming support and enthusiasm for his plan from Longstreet, he was soon disillusioned by the attitude and tone adopted by his top corps commander.

Lee had not rode far along Seminary Ridge when the thunder of cannon drew his attention to his left flank. Here, before Lee’s courier had chance to reach Ewell with his instructions for the day, Union General Henry Warner Slocum, commanding the Union right wing had decided to re-establish his line as it had been before the Confederates under General Johnson had taken over their rifle pits on Culps Hill. Slocum’s attack began at 3.45am, and wrecked any chance of combining Ewell’s Corps effectively in the planned offensive. Although the Rebels eventually had to abandon their hard won gains, they still put up a stubborn resistance until they were finally forced off the hill and back to their original line along Rock Creek at its base.

None of this seems to have ruffled Lee, even though his original plan was now dropping to pieces, he still had the mind-set to deliver a crushing blow to the Union centre, and the fact that Ewell’s Corps would no longer play any contributing role in it did not faze Lee in the slightest.

Eventually arriving at Longstreet’s headquarters just before dawn, Lee was pleased to find that the general appeared to have regained his usual fighting spirit, despite the losses that his corps had sustained in the previous days fighting. The heavily bearded Georgian pointed out to Lee that he still considered a turning movement around the Union left flank to be feasible, but his mood soon changed when his chief stated categorically that, “The enemy is there,” motioning with his hand towards the Union centre along Cemetery Ridge, “ and I am going to strike him.” [12]Earl J.Hess, Pickett’s Charge-The Last Attack at Gettysburg, page, 6 These words plunged Longstreet back into his cloak of depression and gloom, for he understood that once Lee had made up his mind nothing would shake his resolve. When asked by Lee how many troops he thought the attack would require, Longstreet said that in his professional opinion it would take at least 30,000 men to reach and breach the Union line, and once again his chief choose to ignore this advice. [13]Ibid, page, 9

What the Confederate commander envisaged was an attack just to the north of the ground Longstreet’s men had attacked the day before. To this end he considered that the fresh division under Pickett, together with Heth’s division (now under Brigadier General James J. Pettigrew), and two brigades from Major General William Dorsey Pender’s, now under Major General Isaac R. Trimble (both from Hill’s Corps), would converge towards a point in the Union line generally considered to have been a small clump of trees, but whether Lee actually used this landmark as a direction finder is open to debate. [14]Ibid, page, 387-388On the right flank of the attacking columns, and supposedly acting in close support, only two brigades, those of Brigadier General Cadmus M. Wilcox and Colonel David Lang took an active part. [15]For an account of the actual brigades and regiments, which did or did not take part in the charge, together with the strange use of depleted units instead of comparatively fresh ones see, Earl J. … Continue reading The number of troops that actually took part in the advance is also the subject of conjecture, since casualty lists were, at best, a matter of guesswork after the slaughter of the previous two days. Only Pickett’s division can be estimated with some certainty – 5,500 infantry with the colours. The other divisions and brigades collectively contributed around 7-8,000 men, giving a total of some 12,000 plus. [16]I have studied the figures given in the numerous sources and consider the above total to be as good as any, and possibly better than most G.J.M

In preparation for the attack Lee had instructed Longstreet to saturate his objective with mass artillery fire, which would breach the Union line prior to the advance of the infantry. Longstreet’s artillery commander, Colonel Edward Porter Alexander deployed seventy-five guns in line north of the Peach Orchard, another sixty-three guns were grouped several hundred meters to the rear and left of Alexander’s line along Seminary Ridge, while a further twenty from Ewell’s II Corps were placed on Oak Hill at the northern end of McPherson’s Ridge to knock-out the Union batteries on Cemetery Hill.

Across on the Union side Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, commanding the centre, had stretched out the 5,500 men of his three divisions so that they could bring every rifled musket to bear to the front, backed by the massed fire from batteries placed in support.

At 11 am an eerie silence fell over the battlefield, only punctuated here and there by the occasional crackle of skirmishing fire or the single report of a cannon. The men of both sides tried to busy themselves digging-in, playing cards or writing letters. Union soldiers along Hancock’s line dismantled the fences around their position, using the stout rails and post to construct breastworks. Officers and soldiers in both blue and grey knew that the lull was the precursor of something momentous.

It came in a hail of flying metal as, at 1.00 pm two Confederate guns announced the signal for the bombardment to commence. Within seconds the peace was shattered as over 300 cannon from both sides took up the challenge hurling their long-range shot across the mile wide valley that separated the two armies.

For over an hour the hillsides erupted with fire, smoke and exploding caissons. The Confederate artillery was prone to firing too high, as well as suffering from poorer quality ammunition (a habit they never seemed to be able to get out of), but still managed to cause much damage to Union troops and equipment in their rear area. Also Alexander, who was monitoring the effects of the bombardment never had a clear field of vision once the valley became filled with black powder smoke, and his judgement on the damage being inflicted was reduced, in the main to listening for the sounds of Union batteries falling silent. His troubles were compounded by the fact that although some of their guns were certainly put out of action, others along the Union line were ordered to cease firing so that they could conserve their ammunition for the infantry attack that was to follow. [17]See, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. III, Page, 357-368 Worried himself about his own depleted supply of long range shot, Alexander sent a hastily written note to Pickett, ‘For God’s sake come quick. The 18 guns have gone (referring to a group of batteries near the clump of trees which, in fact had been replaced by others who had not commenced firing). Come quick or my ammunition will not let me support you properly.’ [18]Earl J.Hess, Pickett’s Charge- The Last Attack at Gettysburg. Page, 125-165Upon receiving this information Pickett immediately rode over to consult with Longstreet, finding him sitting on a post and rail fence observing the bombardment. Pickett dismounted, passed Alexander’s note over to him and, as Longstreet failed to show any sign of acknowledgement, Pickett asked, “General shall I advance?” The only gesture that Longstreet made was a nod of the head, thus the order for one of the most famous charges in military history was not communicated either in writing or in words. [19]This is a strange story, as we seem to have only Pickett’s and Longstreet’s account of just what took place. The fact that Pickett never wrote an official account of the charge, and if he did … Continue readingAssuming that Longstreet was not “nodding-off”, Pickett saluted saying, “ I shall lead my division forward, sir.”

Gorgeous George Pickett, his perfumed dark brown hair cascading in ringlets down to his shoulders, and wearing a tailor made new uniform spurred his horse along the line of his division halting to look at the faces of the men he was about to lead for the first time into battle. Then standing up in the stirrups he raised his sword exclaiming, ‘Up men and to your posts! Don’t forget today that you are from old Virginia!’

While Pickett was forming his division for the assault, Longstreet, finally arousing himself from his lethargy, mounted his horse and rode out to consult with Alexander. Upon enquiring about the effect the Confederate fire had had upon the Union position, Longstreet was chagrined to learn of his artillery commander’s worry about the almost exhausted state of his own ammunition. This fact caused Longstreet to order Alexander to stop Pickett until supplies could be replenished, yet another case of passing on the responsibility of the attack to someone else. Alexander quickly explained that the supply trains had been moved further back, out of the range of Union gunfire, and that the time taken to replenish his ammunition would allow the enemy to recover and resupply themselves. These facts convinced Longstreet that any further delay would place the whole plan in jeopardy, and with a heavy heart he accepted what fate would decide. [20]Earl J.Hess, Pickett’s Charge- The Last Attack at Gettysburg, Page, 158-162

At 2.30 pm the Confederate regiments and brigades began to form their lines of battle. Pickett’s division, forming the right of the line, deployed the brigades of Kemper and Garnett in the first line with Armistead’s to the rear of Garnett in support. To Garnett’s left, at a distance of about 500 meters Pettigrew’s division began to deploy, with Trimble’s two brigades to his rear. The advance of Pickett’s division would consist of a series of left obliques, bringing it into line with Pettigrew and Trimble whose march would be direct. The two converging lines were stretched out for over a mile, this distance reducing as the divisions came together for the final push against the Union centre. [21]See Map. To go forward with the infantry, Alexander had managed to scrape together 18 cannon, the only ones with enough ammunition remaining to support the attack.

Eyewitnesses have described the scene, as the long lines of Confederate infantry broke from the cover of the trees. One observer noted, “ They seemed impelled by some irresistible force…the glittering forest of bayonets in superb alignment moved forward with a determined, unhesitating step.” [22]Edwin B.Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command, Page, 503 Unfortunately Union cannonballs had no such sentiments.

Pickett’s three brigades moved through the Confederate gun line for about 100 meters and commenced the first left oblique, as they did the Union guns opened on them with devastating effect. Men fell in scores along the advancing line; one shell alone exploding among the 11th Virginia Regiment killed or wounded sixteen men. [23]Earl J.Hess, Pickett’s Charge-The Last Attack at Gettysburg, Page, 172 Each time a gap appeared the stalwart Rebels closed ranks and pressed on, but men were falling so rapidly that the continuing left shoulder movements to dress the lines caused an involuntary slowing of the pace, and consequently allowed more fire to be poured into their midst. The Union batteries at the lower end of their line enfiladed the whole of the Confederate formation, and to add to their discomfort the troops in the left flank brigade under Colonel John M. Brockenbrough, who were trailing a little behind the main line, drew the attention of Major Thomas Ward Osborn’s 31 Union cannon situated on Cemetery Hill. As they tried to recover from this pounding the Confederates were then assailed in the flank by a withering fire from the 8th Ohio Regiment, which had been pushed forward from their main line. All this proved too much and Brockenbrough’s men fell back in disorder to the rear, sowing confusion in Trimble’s ranks as the fugitives pushed through them in their struggle to get clear. [24]Ibid, Page, 190

Over on the right, Pickett’s line also came under enfilading fire from the Vermont regiments under Brigadier General George Stannard who had also advanced his brigade from the main Union line and then swung it 90 degrees to the right. The fire from these troops caused Kemper’s Confederate brigade to crowed-in to their right, mingling with Garnett’s troops and giving the Union artillery and infantry an even denser mass to fire into.

As they drew closer to the Union position the rebel’s pace quickened, and soon they broke into the “double-quick”, not only to come to grips with their foes, but also to get clear of the terrible killing fields of Union fire. Pettigrew and Trimble’s divisions also became intermixed, but continued to push on to the Emmitsburg Road, some elements even managed to get within 10 meters of the Union line (see photograph below), but here they were finally halted, shattered and spent. Many troops lay flat on the road waving hats, handkerchiefs and paper as a sign of surrender, [25]Edwin B.Coddington, The Battle of Gettysburg, A Study in Command, Page, 514 the remainder fell back in confused groups to their own lines.

As Garnett’s brigade was endeavouring to clear the fence on the opposite side of the road, Armistead’s regiments came up in their rear adding their impetus and causing the whole mass to roll forward. Kemper’s regiments also came packing in from the right, desperately trying to get away from the Federal flanking fire. “Boy’s, give them cold steel.” shouted Armistead as he took off his hat and jabbed it onto the point of his sword. Garnett and Kemper went down, but somehow Armistead and 150 men managed to reach the Union gun line unscathed. Here they burst upon the line of Brigadier General Alexander Webb’s Pennsylvanians. Only having been in charge of his brigade for a short time, Webb tried to urge his men on by grabbing the standard of the 72nd Pennsylvania Regiment, only to have it torn back from his grip by its burly bearer who did not recognize his commanding general. The brigade moved forward a few steps, fired a volley into the crowd of Rebels, but refused to charge. Webb dashed to another regiment, the 69th Pennsylvania, who also refused to budge. It seemed that no one in the brigade knew just who this berserker general was. [26]Curt Johnson and Mark McLaughlin, Battles of the American Civil War, Page, 94

Armistead, as the only general officer to reach the Union line unscathed soon drew the attention of the enemy’s fire. He took three bullets, one in the leg, one in the arm, and one in the abdomen. “Pressing his left hand on his stomach, his sword and hat…fell to the ground. He then made two or three staggering steps, reached out his hands trying to grasp the muzzle of what was then the 1st piece of (Union general’s) Cushing’s battery, and fell.” [27]Earl J.Hess, Pickett’s Charge-The Last Attack at Gettysburg, Page, 263

Having pierced the Union line, the troops who managed to follow Armistead were too few and too disorganised to hold on. Here the charged collapsed in what has been described as the ‘High water mark’ of the Confederacy. Although two supporting brigades under Lang and Wilcox did attempt to come forward, they only served to cover the retreat of the shattered Rebel formations. Of the 12,000 or so men who had been involved in the charge over 6,000 were either killed or wounded.

As the remnants dribbled back to Seminary Ridge, General Lee rode out to meet them. Doffing his hat, he tried to steady his men’s nerves with praise tinged with sorrow, telling them that it was all his fault, and that he had realised too late that he had asked them to do the impossible. Reining in his trusty horse, Traveller, he told Pickett gently to form what remained of this division in the event of a Union counter attack. Pickett, looking bewildered and gaunt replied, “ General Lee, I have no division.” Lee continued quietly, “Come, General Pickett, this has been my fight and upon my shoulders rests the blame.” George Pickett never forgave his commanding general for destroying his division. [28]Earl J.Hess, Pickett’s Charge-The last Attack at Gettysburg, Page, 326

This was not quite the end of the battle, while Pickett’s men were being decimated on Cemetery Ridge, some miles further to the northeast, General J.E.B. Stuart’s Confederate cavalry, following Lee’s orders to try and get around the Union position, had failed in their attempt to cause disruption in the enemy’s rear. Clumsiness and muddle caused the adventure to be something of a fiasco, and Stuart’s troopers were forced to withdraw. As a final gesture, Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick (known to his men as “Kill Cavalry.”) had, at around 5.30 pm, received the news of the defeat of Pickett’s charge. Seeking to make a name for himself in the annals of warfare, Kilpatrick ordered Brigadier General Elton J.Farnsworth to charge the Rebel line on their right flank, considering, somewhat naively, that he could roll-up their line. Protesting vigour, Farnsworth said that he thought it would be suicide to commit his troopers to attacking enemy units who had not taken part in the attack, and who were prepared to meet any eventuality after that event. Nevertheless Farnsworth was ordered to carry out his advance, the result of which proved his point, and cost him his life, as well as those of several dozen of his command. [29]Edwin B.Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command, Page, 524-525

The Losses in this great battle were more poignant than is usual in war. Not only was it a nation in conflict with itself, but also families within that same nation that fought bitterly against one another for what they each firmly believed. Thus the cost in dead and wounded, well over 50,000 men from both sides, left little to show other than how cultural ideas and dogma can tear countries and families apart.

After standing his ground for another day on the corpse littered fields of Gettysburg, General Robert E. Lee finally, on July 5th, withdrew his army back to their old campaigning grounds of Virginia. Almost another two full years of conflict and bloodshed lay ahead, but the Army of Northern Virginia never again took the offensive.

And what of George Pickett?

I began writing this little article so that the layman would be able to comprehend the relevant points of the battle. After combing the WEB for a decent critique of the battle, and of Pickett himself, I found nothing but bias and dross. This is the reason I have not come to any firm conclusion concerning General Pickett’s behaviour and whereabouts during the charge. For those interested may I suggest the following, Lesley J.Gordon, General George E. Pickett in Life and Legend. The University of North Carolina Press (Paperback edition), 1998.

Photographs

Bibliography.

| Boatner. Mark M. | Biographical Dictionary of the American Civil War 1861-1865, Cassell, London. 1973 Edition. |

| Thomas Yoseloff, | Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol III, Thomas Yoseloff, New York and London. 1956 Edition. |

| Coddington. Edwin B. | The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command. Paperback Edition. Charles Scribner’s and Sons, New York. 1984. |

| Foote. Shelby. | The Civil War, A Narrative. Paperback Edition. Pimlico Press. London, 1994. |

| Hess. Earl J. | Pickett’s Charge-The Last Attack at Gettysburg. University of North Carolina Press, 2001. |

| Johnson and McLaughlin. | The Battles of the American Civil War. Book Club Associates. Washington and London. 1978. |

Graham J.Morris

November 2003

Addenda

Brian Hampton has informed me that since writing the article below he has begun to have doubts about the validity of some of the statements and claims put forward by the Pickett family. In light of other erroneous material published by La Salle Pickett, the General’s wife, the reader is advised to approach the subject with an open mind.

Both the author and I would like to apologise for any typographical and grammatical errors that occur both within this article, and on the site as a whole. I will endeavour to remedy any mistakes, which may be attributed to hastily edited pages.

Pickett’s Battle ReportConsidering the extreme notoriety of and controversy surrounding the charge on the Union center made by the divisions of Pickett, Pettigrew, and Trimble, one might be led to believe one of the most important historical documents in existence would be Pickett’s official report on his part in the battle of Gettysburg. Unfortunately, this report doesn’t exist. This is not an amazing fact in and of itself. Wounded officers often failed to file reports, and, of course, officers killed in battle were unable to file reports, and their subordinates who took command often were not in a position to compose a comprehensive report of battle. General Hood, who was wounded at Gettysburg, never filed an official report, but, in a letter to Longstreet after the war, gave his version of events. None of these reasons explains Pickett, however, which leads to an interesting — some would say suspicious — story. Pickett did file a report regarding the operations of his division during the Gettysburg campaign; however, General Lee ordered Pickett to destroy the report, stating that he felt the content would cause divisiveness within the army. No one is certain when he wrote this report, although it is generally believed it was sometime shortly after the battle itself — a day or two –, which would have made it one of the most timely reports of the campaign. (Most of the official reports were not written until at least a month after the battle, some longer than that.) The question is, then, what was in the report that would cause such divisiveness, at least to a point that General Lee would consider it a danger to the morale of the army? Some historians and critics have suggested that Pickett’s report was critical of Longstreet’s handling of the charge. Pickett was, after all, caught in the middle of the exchanges between Longstreet and E.P. Alexander in which Longstreet looked for any reason at all to avoid ordering the assault. Pickett saw it all, from Longstreet’s stubborn resistance to the charge to Alexander’s insistence that the decision to order it must remain with the commander, not him. Pickett would have been aware of Longstreet’s failures — if indeed there are any — to support the advance and the carry out Lee’s orders. If, as some contend, McLaws and Hood’s division were supposed to be a part of the assault, Pickett would have been aware of this fact. If Pickett had died or never said another word about the charge, the belief that he was critical of Longstreet might be a somewhat valid assumption; at the very least it would have been a valid point of view. However, the story does not end with Lee’s admonition and his order to destroy the report. Pickett’s attitude after the battle and the fact that he did make some statements later in life give hints as to the possible content of his report. After the war Pickett once visited General Lee, a visit he refused to make alone. After the visit, the atmosphere of which was reported to be somewhat cool and stiff, Pickett is reported to have said that General Lee had had his division slaughtered. After the battle itself Pickett refused to even attempt forming his men into a line to attempt to repulse the expected Union counter-attack. He stated that he had no division left, that his men who were still standing were too demoralized to fight, and even if they weren’t, they had no officers to lead them. This latter view is a little exaggerated, but it gives insight into what was going through Pickett’s mind after the battle. Pickett was so distraught at the outcome of the assault on Cemetery Ridge that many report that he set to work writing his report of battle immediately. Pickett’s state of mind and his opinions following the war lend credence to the belief that Pickett was critical of not just the assault itself, but of General Lee’s part in it. It was General Lee’s plan. General Lee did take an active role in organizing and lining up the troops. General Lee did continue to insist that the assault was made despite the severe doubts as to the possibilities of success by General Longstreet and others. The question then becomes, was Pickett critical of Lee himself? Was Lee, in ordering the report destroyed, attempting to protect his own reputation? The latter scenario is unlikely. General Lee was not that vain. What is more likely is that Pickett’s report contained criticisms of the commands of Pettigrew and Trimble who were positioned on the left of Pickett’s division during the assault. The post-war controversy that erupted over the role of these men in the charge lends credence to this theory. Pickett’s men maintained that Pettigrew and Trimble were supposed to support the charge, as opposed to being an integral part of it, and that they failed in their duty. This is false, but the fact that many of Pickett’s men and likely Pickett himself believed this to be true is undeniable. Whatever particulars his report contained, it is evident that Pickett was not critical of Longstreet whom he maintained a warm relationship with during the rest of the war and after. Indeed, none of Pickett’s men were ever openly critical of Longstreet. If Pickett had felt Longstreet was responsible for his division’s repulse wouldn’t it be more likely that Pickett would have had similar comments about his corps commander as those he had for his army commander? The Pickett’s and Longstreet’s remained close and never seemed to have harsh words for one another. One final piece of the puzzle cannot be considered historical fact, but is interesting nonetheless. The story in the Pickett family is that George Pickett made a copy of his report and sent it to “Sally,” his soon-to-be wife. This copy supposedly remained with the family, but at some point became either lost or destroyed. As the harsh words against Longstreet were being leveled during the latter part of the 19th century, someone in the Pickett family stated that he knew of the existence of a document which many historians would find most interesting. The tone of his comment, as reported, tends to indicate that the document would redefine the then common perceptions regarding the planning and execution of Pickett’s Charge. (It is important to note that at this time, Longstreet was being blamed by Early, Pendleton, and Gordon as well as a host of historians for losing the battle of Gettysburg and not obeying Lee’s orders.) Glen Tucker, a meticulous researcher and historian who wrote books like High Tide at Gettysburg and Lee and Longstreet at Gettysburg researched the mystery of Pickett’s report exhaustively, gaining the full support and cooperation of Pickett’s descendants. After going through every piece of family memorabilia and all of its artifacts, he and the family were unable to uncover a the copy of the report. This is a tragedy, but the knowledge that the report did once exist and the statements made and handed down by Pickett’s descendants throughout the years do, at least, give a glimmer of what the report might have contained. At the very least, Pickett’s report and Lee’s ordering its destruction are an important part of the history of the Army of Northern Virginia and especially of the role of Longstreet in the battle of Gettysburg. Sometimes the important facts of history are not known necessarily by what historians find, but by what they don’t find and why. The mystery of Pickett’s Report is just such a piece of history and the study of that mystery is essential to any understanding of the battle of Gettysburg. |

References

| ↑1 | The above information was taken from, Cassell’s Biographical Dictionary of the American Civil War 1861-1865. Mark M.Boatner III Editor. Page.651 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Edwin B.Coddington. The Battle of Gettysburg, A Study in Command. Page 11. |

| ↑3 | Ibid, page. 12. |

| ↑4 | Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Vol, III, page. 437-438. |

| ↑5 | Edwin B.Coddington, The Battle of Gettysburg, A Study in Command. Page, 11 |

| ↑6 | See James Longstreet, “Lee in Pennsylvania,” Annals, 417. Also his account of, Lee’s Invasion of Pennsylvania,” Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol.III, page, 245-247. The subject is discussed at some length in Edwin B. Coddington’s, The Battle of Gettysburg, A Study in Command. Notes. Page, 601 |

| ↑7 | Edwin B.Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command, page 263 |

| ↑8 | Ibid, page. 315 |

| ↑9 | Ibid, page, 377 |

| ↑10 | For an account of this stage of the battle see Brevet Major General Henry J.Hunt’s description in, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol III, page, 290. Also a very detailed description is given in Edwin B.Coddington’s, The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command, Page, 359 |

| ↑11 | See, Shelby Foote, The Civil War, A Narrative, Vol II, page, 526 |

| ↑12 | Earl J.Hess, Pickett’s Charge-The Last Attack at Gettysburg, page, 6 |

| ↑13 | Ibid, page, 9 |

| ↑14 | Ibid, page, 387-388 |

| ↑15 | For an account of the actual brigades and regiments, which did or did not take part in the charge, together with the strange use of depleted units instead of comparatively fresh ones see, Earl J. Hess. Pickett’s Charge- The Last Attack at Gettysburg. Page, 36-75 |

| ↑16 | I have studied the figures given in the numerous sources and consider the above total to be as good as any, and possibly better than most G.J.M |

| ↑17 | See, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. III, Page, 357-368 |

| ↑18 | Earl J.Hess, Pickett’s Charge- The Last Attack at Gettysburg. Page, 125-165 |

| ↑19 | This is a strange story, as we seem to have only Pickett’s and Longstreet’s account of just what took place. The fact that Pickett never wrote an official account of the charge, and if he did there is some evidence to support the case that Lee himself ordered it destroyed makes one wonder who was covering up for who? |

| ↑20 | Earl J.Hess, Pickett’s Charge- The Last Attack at Gettysburg, Page, 158-162 |

| ↑21 | See Map. |

| ↑22 | Edwin B.Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command, Page, 503 |

| ↑23 | Earl J.Hess, Pickett’s Charge-The Last Attack at Gettysburg, Page, 172 |

| ↑24 | Ibid, Page, 190 |

| ↑25 | Edwin B.Coddington, The Battle of Gettysburg, A Study in Command, Page, 514 |

| ↑26 | Curt Johnson and Mark McLaughlin, Battles of the American Civil War, Page, 94 |

| ↑27 | Earl J.Hess, Pickett’s Charge-The Last Attack at Gettysburg, Page, 263 |

| ↑28 | Earl J.Hess, Pickett’s Charge-The last Attack at Gettysburg, Page, 326 |

| ↑29 | Edwin B.Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command, Page, 524-525 |

Hi once again Jeff!

Please send the photographs along. I would be very pleased to have them.

Send them via – graymo1815@gmail.com

Many thanks for visiting the site once more,

Graham

Dear Sir,

You may recall that I sent you some photos that I took of the Gettysburg battlefield some years ago. I am gratified to see they are still in place at the bottom of the page for that article. I do have some photos of the Antietam field taken in March 0f 2002. As you can tell by my earlier photos, I am in no way a professional photographer. However, I do have some a photo of the Miller Cornfield and Dunker Church that might adorn your site. I ask no recompense, and you are free to use or reject them at your discretion. My feelings won’t be hurt if you don’t want them. If you want to take a look at them, please respond at the email address below. Love the panoramas!

Hi once again Jeff!

Please send the photographs along. I would be very pleased to have them.

Send them via – graymo1815@gmail.com

Many thanks for visiting the site once more,

Graham