The fighting qualities that made the Swiss one of the most feared and respected military powers in Europe had been nurtured over many centuries, and although farming and the raising of livestock was the major source of their economy, they were not by nature a placid or timorous people. Thus a strong sense of independence was to be found throughout the scattered towns and communities, such as the Waldstätte or ‘Forest Cantons’ around Lake Lucerne – Unterwalden, Uri and Schwyz – which, in 1291, formed an alliance (Everlasting League) against the, what they considered, oppressive Austrian Habsburgs.

The battle of Morgarten, 15th November 1315, which, according to the eminent German military historian Hans Delbrück, ‘was buried beneath a rubble-like mass of legends and fables,’ [1]Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 551 shows us the way in which the Swiss first began to organize themselves into a coherent fighting force. The fierce nature of the Canton of Schwyz propelled the other Forest Cantons into an armed confrontation with Austria by sacking the monastery of Einsieden, which was under Habsburg control. Thereafter Duke Leopold marched an army of some 5,000 men, including 2,000 knights, against the Schwyzers in order to punish them for their aggression.

It is worth quoting Delbrück here at some length so that a better understanding of the Swiss nature and intent can be established during the time period under discussion in this article.

‘…it was not a question of the desperate revolutionary rising of a peaceful peasantry but rather of a well-planned struggle of a warlike community with battle-hardened leaders under the command of their own top authority. In the case of men with such military experience, we are justified in filling in, in keeping with the concept of a well planned, systematic action, the individual reports and indications of their acts that have been preserved for us.

From ancient times, people in mountainous areas have strengthened their natural protection against enemy attacks by blocking the entrances in the valleys through some kind of man-made works. In Switzerland such obstacles were called “letzi” or “letzinen,” which is related to the word “lass,” whose superlative form is “letzi”; there are still eighty-five of them that can be confirmed today. The Rӧuschiben letzi is supposed to be from the pre-Roman period, the Serviezel letzi and also the foundation of the one at Näfels are supposed to be of Roman origin, and four others are thought to be from the fourth century. In Schwyz six litzinen can be confirmed; they covered not only the entrances to the country, but a few of them also consisted of palisades in the Vierwaldstätter Lake and Zuger Lake in order to prevent landings. Certainly some of these installations reached back into the thirteenth century and even earlier, long before the battle of Morgarten. When the great decisive battle for their liberation from the power of the [Habsburgs] now approached, the Schwyzer had nothing to do that was more important than reinforcing their litzinen. There is also in existence a document indicating that the community of the march, [boundary or border between two countries or states] the people of Schwyz, in 1310 sold parcels of the land to two brothers, in order to apply the profit “an die Mur ze Altum mata,” that is, the letzi at Rothenthurm bei Altmatt, of which one tower still exists today. [2]Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 522

Knowing full well that the Schwyzers had been strengthening their letzinen, Leopold did not take the roads along the right or left of the Zuger Lake towards Arth, but choose an alternative route along the east bank of Lake Aegeri. During this time the Schwyzers had been reinforced by contingents from Uri and Unterwalden, but even with these the whole Swiss force only amounted to just over 1,700 men.

Unfortunately for the Austrians their route passed through a narrow defile which the Schwyzers had blocked off with tree-trunks and boulders, causing the Austrians column to veer off the road to the left and take a narrow path leading to the village of Schafstetten. Here their progress was further impaired by yet more felled trees from behind which a group of Schwyzers assailed them with stones and arrows. As a consequence of this the Austrian column became compacted, as more troops arrived, thus causing a bottle-neck of men and horses. To complete the discomfiture of the Austrians, the Schwyzers now sent a further detachment down from their hidden position on the wooded slopes to block off their escape, while the main body of the Swiss came charging down the hillside throwing stones and causing mayhem with their halberds and axes. With no room to manoeuvre, the Austrians were cut down in hundreds, while those that attempted to escape were forced into marshland where they were slaughtered. The total Austrian losses will never be fully known, but at least 2,000 may have been killed, since the Swiss, in general, had a policy of not taking prisoners. The Schwyzer losses were no more than a hundred killed and wounded.

The battle of Morgarten had two lasting consequences; firstly it gave the Swiss the confidence to flex their military muscle still further; secondly it instilled in the minds of their commanders the idea that, lacking the means to wage a war of attrition because of their agrarian economy, they would have to adapt to the offensive in all their battles in order to obtain a swift and decisive result. [3]Showalter. D.E, Caste, Skill and Training: The Evolution of Cohesion in European Armies from the Middle Ages to the Sixteenth Century. The Journal of Military History. Vol. 57, page 12

And so to war.

The various Swiss cities and cantons were not averse to fighting among themselves. The battle of Laupen (21st June 1339) was fought between Berne and Fribourg, who had allied itself with Burgundy and other related duchies, Waadt, Aarburg, Greyerz, Valengin and Neuenburg, to stop Bernese expansion. For their part the Bernese called upon the ‘Three Forest Cantons’ for assistance, which was given, albeit in return for payment.

Fribourg and her allies laid siege to Laupen on the 9th June, and on the 21st the Bernese relief army arrived before the walls of the beleaguered town. The strengths of the opposing armies are variously given in the sources at 10,000 – 15,000 for the Fribourg/Burgundy alliance, and 6,000 – 8,000 for the Bernese, however maybe the figure of 6,000 men on each side would be a fair estimate. The ensuing battle proves interesting, as it highlights the changes that were to take place both in Swiss tactics and weaponry.

Near the small village of Bremberg, just to the east of Laupen, the two armies drew up for battle. The Bernese placed the contingent from the forest cantons, in column, some 1,000 strong, facing the Burgundian mounted knights on the left. The main body of their infantry, around 3,000 men, were formed in column, fifty men wide and fifty men deep. A further 2,000 troops were held as a rear guard, forty men wide and forty deep; hand gunners and bowmen covered the front of each column.

The exact formation of the Fribourgers and their allies is not precisely known, other than, as stated above, that the Burgundian knights took station on their right. Presumably the various contingents from each of the allied duchies would have formed themselves in column, while the Fribourgers were massed in a solid phalanx.

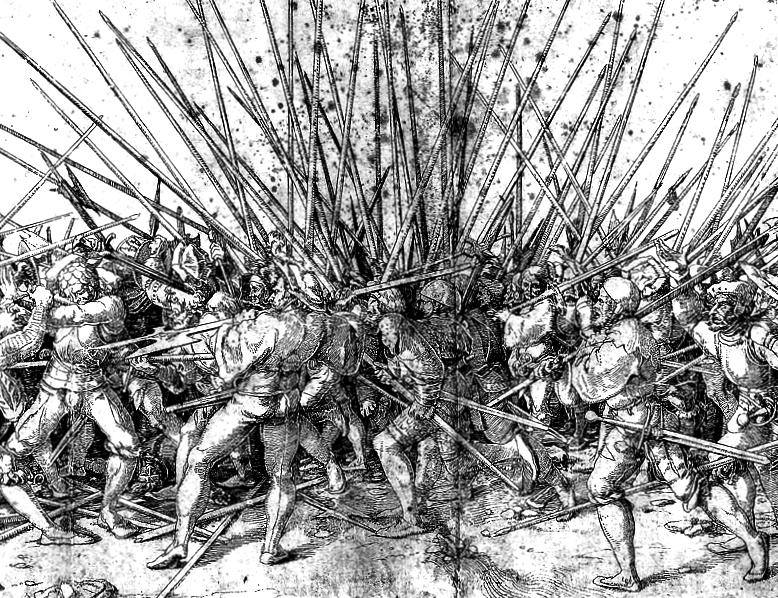

With the Bernese drawn up on higher ground, the allies decided to send a force to outflank their position, ‘…while the knights paraded in front of the enemy position and the young lords were dubbed knights.’ [4]Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 563 By the time the outflanking column was in position it was near evening. Nevertheless, upon the approach of these troops the Bernese rearguard quit the field. Luckily the rest of their troops stood firm as the allies, seeing the panic caused by their enveloping manoeuvre, launched a frontal assault. This was countered by the Bernese, who immediately went over to the offensive themselves, causing the Fribourgers to break and scatter. The column of the Forest Cantons had also moved forward but were checked by the Burgundian knights and forced to halt, and although their “hedgehog” formation of halberds protected them on all sides from any serious penetration, they nevertheless would have probably been defeated when the Burgundians brought up their archers and crossbowmen. Fortuitously for them, the Bernese had cleared the field before them and now turned against the knights, in a manoeuvre that was to show how infantry had once more become a tactical factor on the battlefield. Now attacked themselves from the rear, the Burgundian knights fled in confusion, many being killed. The allied troops who had originally been sent to attack the Bernese rear failed to contribute anything more to the battle and, ‘Presumably, the men were not under the control of their leaders or had no true leadership at all and were pursuing the fleeing enemy [the Bernese rearguard] in order to take prisoners and to plunder.’ [5]Ibid, page 564 Here we must consider one of the major factors in warfare – command and control.

The battle of Laupen shows so much strategic and tactical thought and leadership on the part of the Bernese that we may well ask who the general was who accomplished this feat. The assumption of a threatening defensive position and the shift from the defensive into the attack remind us of Marathon, and, strangely enough, there exists on the Bernese general a source account quite similar to that of Militiades. To be sure, the contemporary source, the “Conflictus,”makes no mention at all of a commander, but this account is completely defective from the military viewpoint. On the other hand, Justinger’s account, in which, of course, legend and history can no longer be completely separated from one another, reports that the knight Rudolf von Erlach held the high command position. This man, very rich and respected, was at the same time the vassal of one of the allied enemies, the count of Nidau, and a burgher of Berne. When the war clouds formed, he freed himself from his feudal lord and placed himself at the disposition of the Bernese. His father had already commanded the Bernese at the engagement on the Dornbühl in 1298, and he himself had “proven himself well in six battles.”The Bernese believed they had found in him the right commander, “that he would show and teach them how they should start and end their affairs, since in war wisdom is better than strength.” [6]Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare. Vol. III, page 564

As well as the need for a strong and respected command, the Swiss also realised that the halberd alone could not deter a determined attack by mounted knights. By adding the pike, which was used by many of the lowland cantons, and was gradually increased in length to as much as fifteen or eighteen feet, their manoeuvrable columns became immune to any challenge from mounted troops. This, plus the inclusion of marksmen within the columns, to counter any action by enemy archers, made the Swiss a formidable force on the battlefield. This was made glaringly obvious at the battle of Sempach, 9th July 1386.

Not being able to avenge themselves after their defeat at Morgarten owing to an ongoing war with Louis of Bavaria, the Habsburgs had called an armistice, not peace, with the Swiss, which was extended from year to year thus allowing the cantons to consolidate. When the Emperor Charles IV died, Duke Leopold III decided to take back Austrian territory now held by the Swiss. This triggered off a succession of alliances between the Swiss cantons: Lucerne (1332), Zürich (1351), Zug and Glarus (1352), and Berne (1353). [7]Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300-1500, page 10

With a considerable increase in strength, the Swiss were now determined to rid themselves of Austrian control altogether and began a systematic campaign of laying waste to areas still under Habsburg rule. This proved too much for Leopold who now advanced against the Confederates with an army of 4,000 men.

At the outset Leopold did not concentrate on attacking Zürich or Lucerne, as the Swiss had anticipated, but moved his forces against the town of Sempach, approximately 10 miles north of Lucerne, knowing full well that the Swiss would move against him and offer battle. As Delbrück states, ‘ In front of Zürich or Lucerne, the conditions for such a battle would have been unfavourable for Austria, since security against one of these large places would absorb a part of his troops. But a small place like Sempach required only a small force to besiege it and left almost the entire army available for the open battle.’ [8]Delbrück.Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 572

The number of Swiss engaged in the battle is once again debatable, many of the sources playing down their numbers to as low as 1,000-1,600. However we have to consider the fact that in many instances of battlefield reporting by clerics and other non-military writers, especially those who hail from the same country as the victors, these figures are normally played down in order to place greater emphasis on a David and Goliath scenario. Having consulted various accounts, I consider 3,000-4,000 to be a fair estimate of the combined Swiss forces engaged at Sempach. [9]Delbrück considers the Confederates to have fielded an army of 6,000 – 8,000

On the of 9th July Leopold came up against the Swiss advance guard near the small village of Hildersrieden, around five miles north-east of Sempach. The Swiss moved rapidly to gain control of the high ground and seeing this Leopold ordered the knights in his “forward battle” to dismount and attack, but cattle enclosures hampered their advance. Notwithstanding this, and despite taking casualties from Swiss bowmen and stone throwers, the knights still managed to get to grips with their antagonists and capture the banner of Lucerne. [10]Delbrück.Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 573 Several accounts mention the weight and superiority of the Austrian ‘pike’, [11]Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300-1500, page 10 which needs some clarification. Knights would normally carry a lance and sword, although the battleaxe and mace were also used. If for some unexplained reason Leopold had equipped his knights with pikes, one fails to see what use they would have been when these troops were mounted, as they were a very unwieldy weapon even for foot soldiers, and took a long time to master for effective use on the battlefield. Therefore the knights probably used their lances, which may have given them a slight edge, allowing for the fact that not all the Swiss units had as yet adopted the pike as their main weapon, and that the halberd was not as effective against a dismounted foe.

Things were not going well for the Swiss advance guard when, fortuitously, their main army arrived on the battlefield and struck the knights in flank causing them to break back in panic. This rearward flight also affected the other Austrian troops moving up in the rear, and the whole mass soon degenerated into a fleeing mob of fugitives, Leopold and many nobles being cut down in the route.

That the Swiss had been lucky in this battle is obvious when one considers the fact that had Leopold awaited the arrival of his main body, before attempting to get to grips with the Swiss advance guard, and had he used all his knights as infantry, then the outcome of the battle could indeed have been very different.

Fighting as well as farming.

At the battle of Näfels (9th April 1388) the Swiss once again took advantage of the letzinen. These protective barriers were used to good effect both on the defensive and the offensive. By allowing the Austrians to penetrate the palisaded earthworks by a tactical withdrawal to higher ground, the Swiss contingent from Glarus were able to defeat them when, instead of pressing on and keeping up the pressure, the Austrians began to loot the village and surrounding farms. Taking advantage of this, and a heavy mist which had descended, the Glarus men counterattacked charging the now scattered, and we may imagine undisciplined Austrians, with showers of arrows and stones and causing them to disperse in total disorder. The engagements at Voegelinsegg (15th May 1403) and Stoss (17th June 1405) also show how the letzinen was used to their advantage by the Swiss, who once again allowed the enemy to penetrate their defences and then attacked their exposed flanks as they passed through. Delbrück informs us that particular mention is made of the hail of stones used by the Appenzellers during their attack in the sources for the latter engagement. [12]Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 585 This stone throwing causes a problem. On a recent visit to Switzerland I enquired about the method used in throwing stones; were they just small hand held pebbles thrown en mass, or were sling-shots used? The general consensus of opinion was that they were hand thrown. Following this up I decided to try out the effectiveness of this method by arranging various groupings of grass and straw dummies, some with fabric covering, others with improvised “armour” made from old sheet metal and flattened-out tin cans. The “missiles” came in various sizes from small 30 – 50 gram pebbles, up to 1 kilogram rocks, the latter proving not only difficult to throw any distance but also very tiring to the arm after four or five casts. The smaller stones could be propelled a distance of around 20-30 meters, but the damage caused was negligible unless a direct hit was scored onto the face. With this being said I consider that, although several hundred stones thrown by hand would have had a demoralizing effect on the enemy, the actual harm they caused was not substantial, other than to horses.

In 1419 the cantons of Unterwalden and Uri turned their attention to the Milanese city of Bellinzona, which controlled several main alpine passes, and although not able to force its capitulation they remained a constant threat to the city. For her part Milan offered to sell the city to the belligerent Swiss but the offer was declined and thereafter in 1422 the mercenary condottieri, Francesco Bussone da Carmagnola, received orders from the Duke of Milan to evict the troublesome Swiss. On the 30th June 1422 Carmagnola, at the head of an army estimated to be over 14,000 strong attacked the Confederates, who numbered around 2,500 men, in their camp at Arbedo. The Swiss were quick to react, and soon formed themselves into square formation and repelled several attacks by Carmagnola’s mounted troops. Realizing the futility of further assaults by his knights the Milanese commander ordered them to dismount and form with his foot soldiers for an all out attack. Unable to deal with the masses sent against them the Swiss began a slow withdrawal, which however would eventually have proved futile given the numbers being thrown against them. Just as all seemed lost a contingent of 600 Swiss foragers arrived on the field allowing the badly mauled Confederate square to cut its way through and make good its escape to the north with the loss of 800 killed and wounded.

As Douglas Miller states:

Arbedo marks a watershed in Swiss military history, for it forced the Confederation to reconsider the effectiveness of the halberd as the principle staff weapon. More than anything else Arbedo drove home the need to equip [all] the Confederate foot soldier with the pike. Shortly after the battle this need was acknowledged at a Diet held in Lucerne and instructions were given to increase the proportion of pikemen in the cantonal contingents.

This decision was to herald the second great period of Swiss military supremacy, for the introduction of the pike as a principle infantry weapon was to revolutionize military thinking and practice. Due to its length the pike could not be handled individually to any great effect, but had to be employed “en mass.” The proper collective handling of the pike would of necessity entail a considerable amount of training. Furthermore, the introduction of the pike meant the subordination of other weapons, if not in numerical terms then certainly in their mode of employment. Thus while the pike gradually became adopted as the main weapon, the halberd was retained to guard the banners together with the two – handed swordsmen and the axe – bearers. However, if a column was halted and the pike locked with the enemy’s front, then the halberdiers and swords – men could always issue from the sides and rear of the column to break the deadlock. [13]Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300 – 1500, page 13

The adoption of the pike was one thing, but in matters of discipline and control the Swiss still had a few lessons to learn. The test came in 1444 when King Charles VII of France allied himself with the Habsburgs and sent an army of over 15,000 men into Swiss territory. The resulting encounter at St Jacob – en – Birs (26th August) saw a small Confederate reconnaissance force of 1,000 men go totally out of control, refusing to obey orders and locking horns for four hours with the whole enemy army. The outcome was predictable, and the Swiss died to a man, but not before taking over 2,000 of their enemy with them. As Delbrück tells us:

The linking with the civil authorities gave the Swiss general levies the basis of military obedience. Despite the authority of the feudal lord or mercenary leader, in the knightly armies the habit of obedience was still very weak. The reason was that this type of warriorhood was based completely on personal skill, bravery, and love of glory, and there was hardly any question of leadership in combat. Even though the Swiss might have been just as brutal on the march or in camp or while plundering as were the mercenary bands of the period, in battle in their closed units, they followed the command, and in dangerous situations their obligation to obey was stressed with special formality… Anyone who fled or cried out for flight was subject to the judge for both his person and his property, or he could be struck down on the spot by his flanking comrade. [14]Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 588-589

It should also have become glaringly obvious that berserker tactics, coupled with the outright disregard of obeying direct orders issued by a commander on the battlefield , must be addressed; a problem that the Swiss would later regret not having rectified.

The Burgundian Wars.

The Burgundian Wars came about as a result of the convoluted dealings between France, Austria and Burgundy. Unable to control the Swiss encroachment on their lands, the Habsburgs turned to Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. By leasing Charles his remaining possessions in the Black Forest and Alsace, Duke Sigismund of Austria hoped that Swiss expansionist policy would push them into a conflict with the powerful Burgundian army, and thereafter they would be dealt a crushing defeat enabling the House of Habsburg to reclaim its former territory. However, Charles the Bold had little interest in a war with the Confederation as his own expansionist plans lay elsewhere. Realising that he had backed the wrong horse, Sigismund now decided to approach the Swiss in the hope that they would attack Charles and thus regain Alsace and his Black Forest possessions, which now appeared to be lost forever to the Burgundians. The broker and paymaster in the deal between the Habsburgs and Swiss was King Louis XI of France, himself a staunch enemy of Charles the Bold. In return for the renouncement of all Habsburg claims in Switzerland (Constant and Eternal Policy 1474), the Swiss agreed to supply a mercenary force to assist Sigismund if he was attacked. By shrewd diplomatic manoeuvrings by both sides, this defensive treaty soon grew into a general alliance to attack the Burgundians. [15]Ibid, page 600 – 601

Charles the Bold’s lands not only included the Duchy of Burgundy itself and Franche- Comté, but also Flanders and Brabant, and he sought to unite these into one complete territory by the acquisition of Alsace and Lorraine. The first clash came at Héricourt (13th November 1474) where a large force of Austrians, Alsatians and Swiss moved to besiege the town. The Burgundian relief force was defeated, and it was a full year thereafter that Charles was able to gather his forces to meet the threat to his empire building plans. While Charles was otherwise engaged, the Swiss went on to plunder the duke’s lands. Attacking the little town of Stäffis on the shores of Lake Neuenburg (Neufchatel), and slaughtering almost the entire population, including the garrison, they thereafter looted the town. Not wishing to miss-out on the “pickings,” the Bernese also moved to secure the fortified passes of the Jura Mountains. However, Charles now appeared with a large army, forcing the Bernese to relinquish their hold on most of these, with the exception of the town of Grandson, which they sought to retain as an advanced post.

The Battle of Grandson 1476

Charles was well aware that by advancing directly on Berne he would in all probability be faced by the whole weight of the united Confederate cantons against him. He also knew that, although they would not leave Berne in the lurch if attacked directly, the other cantons might not move swiftly to her assistance if he only attempted to regain Grandson, as they were not all in agreement with Bernese policy. [16]Ibid, page 607

Charles laid siege to Grandson in late February 1476 and after a brief resistance the garrison capitulated under the false impression that Charles would show clemency. This was not forthcoming, and every one of the 500 defenders was either hung or drowned in the lake, possibly as an example of Charles’s displeasure for the Swiss treatment of the victims at Stäffis.

The slow build up of the Swiss relief forces allowed the Burgundians to set up a formidable defensive position around their camp, well protected on all sides and amply supplied with artillery. Charles had an army of over 14,000 men, including 3,000 mounted troops, back-up by 100 cannon; although the Swiss army outnumbered him by some 5,000, his position and firepower would have made this superiority in numbers negligible. But this was not Charles’s style, and he choose to move out of Grandson to the village of Concise, about 7.5 kilometres north east, where, on 2st March, his forward units collided with a Confederate foraging party of 2,500 men while setting up camp. The engagement now escalated as Charles arrived at the front and ordered his hand gunners and archers, the latter containing English long bowmen in Burgundian service, to scale the vineyard covered slope and drive back the Swiss skirmishers:

From a theoretical viewpoint, the situation was as favourable as possible for the Burgundian army. Both armies were still in the approach march, but the Burgundians were crossing a plain, while the Swiss were passing through a difficult pass. We must therefore assume that the Burgundian army could be assembled and deployed faster than the Swiss. It could then attack the Swiss, who were still involved in their deployment, and if it succeeded in throwing them back, they would necessarily have been pressed together and held up at the entrance of the defile, suffering heavy losses.

But the characteristic composition and tactics of the two armies made this manoeuvre, quite logical in itself, impossible for the Burgundians. The road along which the Swiss were moving up did not emerge directly from the wooded mountains onto the plain, but gradually sloped downwards across hill planted with vineyards. On this terrain it was hardly possible for Charles to bring into action the two arms on which he relied the most, his knights and his artillery. If he had had only the powerful mass of his marksmen move forward in the attack, they would perhaps have obliged the Swiss to move back into the pass, but alone they could not inflict a real defeat on them, since they could not trust themselves to move up very close to the enemy or to allow a hand –to – hand fight to develop. [17]Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare.Vol. III, page 609-610

Unfortunately for the Burgundians, Charles decided to allow the Swiss time to gather their forward units, amounting to close on 10,000 men, into a solid square formation which now began to descend onto the plain.

In all probability Charles imagined that he had the whole Confederate army to his front when, in fact, a further 9,000 Swiss were still approaching the defile. Undaunted Charles ordered several detachments of men-at-arms to attack the flanks of the Swiss column, while he drew back his forward troops so as to unmask his artillery. The fire from the Burgundian cannon, although not accurate, nevertheless caused a number of casualties in the tight packed Swiss formation, while the flank attacks made by the Burgundian men-at-arms forced their skirmishers to fall back into the square. Taking this as a sign of wavering on the part of the Swiss, Charles himself now led his mounted lancers against the front and right flank of the pike brisling Swiss square, while the Burgundian horse under Château-Guyon also attempted to attack it from the rear:

‘Twice Château-Guyon attempted to wrench the banner of Schwyz from the hands of the ensign before being forced back. His horse was slain under him, and he was himself felled by a Bernese horseman named Hans von der Grub. A man from Lucerne, Heinrich Elsner, succeeded in seizing the banner bearing the golden cross of St Andrew.’ [18]Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300-1500, page 24.

Charles the Bold also had his horse killed during this engagement, but managed to extricate himself from the fighting, and now ordered a re-grouping of his knights so as to allow his artillery to soften up the Swiss square. This proved to be a costly mistake, as just at this particular moment the other columns of Swiss began to arrive on the field, and mistaking the withdrawal of their knights as a retreat rather than a tactical manoeuvre, the remaining Burgundian forces broke in panic. Soon the whole army, with the exception of the knights under Charles’s immediate command, was in full flight from the battlefield, and although he tried desperately to stave off disaster, he was eventually forced to quit the field and follow in the wake of his shattered forces. The Swiss did not follow-up their victory with a full blown pursuit, but contented themselves with collecting the enormous amount of stores and booty left behind by their routed foes, which included over 100 cannon. [19]Some of the sources mention 400 cannon abandoned by the Burgundians. This seems far too excessive. Not only is it more guns than Napoleon had at Waterloo, it would also have taken thousands of horses … Continue reading The Swiss lost some 200 men killed and wounded, while the Burgundian casualties were also light and amounted to no more than 300-400.

What the battle of Grandson proved was the ineffectiveness of mounted knights when pitted against the massive pike square, which became gradually honed into a highly manoeuvrable unit on the battlefield.

The Battle of Murten (Morat) 1476

By allowing Charles the Bold to retire from the battlefield unmolested, the Swiss gave him a breathing space in which to reorganize his forces. Setting up his headquarters in Lausanne, the Duke soon managed to raise an army of close to 18,000 men, and within two months of the disaster at Grandson he was once again ready to take the field.

For their part the Bernese discontinued their policy of retaining outposts too far forward, with the exception of the one at Murten, which is situated some 23 kilometres from Berne, blocking the northerly road from Lausanne. The southerly approach was also obstructed by the city of Fribourg. As Delbrück informs us:

Consequently, Charles was obliged first to attack one of these two places. There would have been no advantage for him to bypass them and move directly on Bern. The Bernese alone would hardly have offered battle in the open field. The duke would have been obliged to besiege the city and would then have been attacked by the relief army in the same manner but under very much more unfavourable circumstances in comparison with what he might expect at Murten or Fribourg. The duke, therefore, had first of all to turn against one of these two cities. Foreseeing this, the Council of Berne had strengthened the Fribourg citizenry with a “supplement” of 1,000 men. The city of Murten, situated on foreign territory [Savoy] and uncertain as to the attitude of its inhabitants, was provided a garrison of 1,580 men under the command of an especially experienced warrior, Adrian von Bubenberg. [20]Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare. Vol. III, page 613

At the end of May Charles began to advance on Murten, which lies on the east shore of the lake of the same name, and on the 10th June he laid siege to the city. Douglas Miller states that the garrison at Murten had been supplied with the bulk of the captured Burgundian cannon taken at Grandson, and that the walls of the city were thus covered by over 400 guns. [21]Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300-1500, page 26 Delbrück makes no mention of this, while various Swiss sources do mention “some” captured guns being used by the defenders. The handling and management of artillery required skill and care, and to have erected firing platforms for over 400 cannon, plus having to drag or lift them up onto the walls seems to stretch credibility a little too far. Therefore I consider that no more than a few dozen guns could possibly have been used, and these would be permanently fixed in their firing positions with little chance of doing any great harm to the attackers once they were under the limited depression of the gun barrels.

Charles’s main camp near the city was not completely enclosed owing to the rising nature of the terrain, but he had constructed a further fortified camp about 2 kilometres from Murten on a wooded ridge overlooking the Wyler Field known as the Bois de Domingue (see map). Here the Burgundians were in an excellent position for receiving any approach of the Swiss from the east with their cannon and marksmen. [22]Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 615 An earthwork and palisade was erected along the ditch at the side of the road that connected the villages of Burg and Salvenach, this was known as the Grünhag, and Charles ordered his forces not directly involved in the siege of Murten to occupy this position on the 15th June, expecting the imminent arrival of the Swiss. Having failed to put in an appearance by the 21st June Charles became puzzled concerning the exact whereabouts of the Confederate army, and rode out himself to investigate. What he actually achieved is debateable, since upon his return he ordered his troops to return to their camp, leaving only about 2,000 archers and hand gunners, supported by 1,000 cavalry to hold the Grünhag. What he probably saw on his reconnaissance was only part of the Swiss relief army, and considered that it was a ploy to draw him away from the siege of Murten. However the full weight of the Confederate army was now concentrated and numbered over 20,000 men, together with 1,500 mounted men-at-arms under the command of Duke Renatus of Lorraine.

At a council of war held on the 22nd June, the Swiss and their allies decided that rather than attacking the Burgundian position frontally, they would envelope it, thus preventing a repetition of Grandson which had allowed their enemy to escape. To this end the advance guard, or Vorhut, of 5,000 troops from Berne, Schwyzer and Fribourg would contain the Burgundians frontally, their left flank protected by the Lorraine horse. The main Swiss square, or Gewalthaufen, numbering over 10,000 men was to follow in echelon on the left; the rearguard, or Nachhut, 6,000 men, would move to the south of the Burgundian camp and cut off any line of retreat. In addition, small contingents from Neuchâtel and Le Landeron would block any attempt by the enemy to escape to the north of Lake Murten. [23]Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300-1500, page 27

On the damp afternoon of 22nd June the Confederate formations began to move forward. Although only thinly held, the English archers and Burgundian men-at-arms defending the Grünhag managed to check the advance of the Swiss Vorhut square, which sustained heavy casualties from arrows and light artillery fire. It took some careful manoeuvring by the Schwyzers to outflank the earthwork, but with this done the defenders broke and fled. [24]Ibid, page 27

In the meantime Charles had been warned of the Swiss attack and gave orders for the trumpets to sound the assembly of his main army. The Burgundian troops, taken by surprise in their camp, began to move forward piecemeal, each unit arriving near the Grünhag only to be met by a stream of fugitives, whose numbers increased as more of their comrades joined the route:

The strongly superior force and aggressive attack of the Swiss, and the confusion and breakup of units among the Burgundians, doomed all efforts to failure. Only a part of the mounted men escaped; the foot troops, including the famous English archers, were overtaken by the enemy horsemen, who were, of course, very numerous and were for the most part cut down. But all the units that were in position around the town of Murten were cut off before they learned what happened. They were all slaughtered or drowned in the lake. [25]Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 621

Charles himself only just managed to escape, while a unit of Burgundians under the command of Count Romont, encamped north east of Murten, beat a hasty but costly retreat, after running into the Swiss formations of Neuchâtel and Le Landelon.

Swiss casualties were probably no more than 600-700, mainly killed or wounded during the advance on the Grünhag. The Burgundians lost over 10,000 men, and once again the whole of their artillery train fell into Swiss hands. Had Charles defended his entrenched forward position with the whole of his field army, plus his not inconsiderable artillery, things would have been finely balanced. The fact that the Swiss were stalled in their initial assault by the few thousand defenders, begs the question of what would have happened if the full weight of the Burgundian army had been prepared and ready? Be that as it may, as a result of the battles of Grandson and Murten Charles the Bold’s fortunes now went into a rapid decline.

The Battle of Nancy 1477

Taking advantage of Burgundian weakness after their debacle against the Swiss, Duke Renatus of Lorraine now moved to reclaim his possessions, forcing the Burgundian garrison at Nancy to surrender on 6th October 1476. Charles could ill afford to allow the city to remain in enemy hands as it was the hinge to his possessions in the Netherlands and Burgundy. Therefore he swiftly began to raise another army in order to reassert his authority, but the forces he managed to scrape together were a pale shadow of former Burgundian strength, numbering less than 12,000 men. For his part, Duke Renatus also found himself unable to raise a substantial force to oppose Charles, and therefore turned to the Swiss for help, but the Confederation was not inclined to mobilize. Instead they (with typical Swiss astuteness) allowed Renatus to recruit an army of paid mercenaries from among the various Cantons for the sum of 4 guilders per man per month. This proved to be such a popular proposition for the Swiss that within a matter of weeks 8,000 mercenaries were recruited. These, together with contingents from Lorraine, Alsace, Austria and France, gave Renatus a formidable army of over 20,000, including 3,000 mounted men-at-arms.

During November and December 1476 Charles had laid siege to Nancy, which, owing to the state of its battered and crumbling walls was not expected to hold out very long. Hearing of the approach of the allied relief army Charles moved out to meet them on 4th January 1477. His plan was to await the arrival of his enemy in a defensive position in a restricted part of a valley south of Nancy. Here he drew up his foot soldiers and hand-gunners in a solid square formation, with cavalry on both wings and artillery to the front. A small stream flowed across the approach march of the allies, and both flanks were protected by woods. The problem with the position was the fact that it was so restricted that it prohibited any manoeuvrability on the part of the Burgundians, and was also hazardous if a retreat was needed in view of a marshland at the rear.

On the bleak and snowy morning of 5th January the allies held a council of war, at which it was decided not to attack the Burgundian position in great strength frontally, but to push forward a strong ‘Forlorn Hope’ to hold the enemies attention while the rest of their army attacked the flanks. The Vorhut, of some 8,000 foot and 2,000 cavalry formed the right wing of the enveloping movement; the Gewalthaufen, 7,000 pikemen and halberdiers, together with 1,000 hand –gunners and 1,000 horse would move around to the left over wooded hills. A very weak Nachhut, of only 800 hand-gunners was held back in reserve to support either of the flanking columns. [26]Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300-1500, page 30 By mid-afternoon it had stopped snowing and the sun broke through the low clouds bathing the battlefield in winter sunlight. The Gewalthaufen together with the Lorrainer cavalrywas now descending the hillside on the Burgundian right flank, and Charles endeavoured to turn his artillery to met the threat, however, being unable to traverse sufficiently the cannon proved incapable of stopping the massive Swiss square from driving home its attack directly into the Burgundian infantry, although their mounted knights did manage to check the Lorrainer cavalry, but only momentarily. Soon the whole of Charles’s infantry block began to disintegrate, and his attempt to bring over archers from the left flank proved too little too late. The Vorhut now came crashing down on the Burgundian left, scattering their horse and overrunning the artillery. It now became a case of every man for himself, and in the ensuing mêlée over 6,000 Burgundians met their death, including Charles himself who, rather like Richard III at Bosworth, was pulled from his horse and battered to death.

If Charles had been a true military thinker he would have realised that the only way to combat Swiss tactics was to employ them himself. His stubbornness in retaining mounted knights in the hope that they would still prove to be the decisive factor on the battlefield is understandable, given that almost every power in Europe, with the exception of the British and Swiss, also adhered to this notion. But if he had dismounted his cavalry and used them to fight on foot in conjunction with his archers and hand-gunners, while also training his remaining foot soldiers to handle the pike, he may well have achieved something close to equality with his enemy.

After the defeat of Charles the Bold the Swiss began to hire themselves out even more readily as mercenaries, and it became almost impossible to prevent them from hiring out to foreign lords and princes. Soon a distinction had to be made between the regular cantonal troops who swore an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy and were paid by the various Cantons to fight for foreign masters, and the free bands of mercenaries who went their own way.

The last major conflict between the Old Swiss Confederacy and the Habsburgs was fought out in 1499, when a local dispute over who controlled some of the mountain passes in the Grison escalated into a full blown war. A major engagement of the war was the battle of Dornach (22nd July 1499). Here the Swiss first came into contact with the Landsknechtes. These well trained infantry had been raised by Maximilian I and had adopted the pike as their major weapon. This, coupled with greater manoeuvrability on the battlefield, marked a distinct shift, ‘in the development of tactical organisations capable of responding to the supremacy of the Swiss.’ [27]Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300-1500, page 31 However, the Swiss still proved themselves superior on the day as the Landsknechtes lacked the community militia background of the Swiss and were not normally kept together long enough to instil any spirit of unity and bonding. [28]Jones. Archer, The Art of War in the Western World, page 178

The Italian Wars 1494

The spasmodic clashes between the Swiss and Italians never resulted in a full – blown war. It was the incorporation of Swiss mercenaries into the French army that proved a tough nut to crack for Italian commanders. Italy was a patchwork of kingdoms and city states, which fought mostly among themselves, having no major land frontier with any country that had a different military system to her own. [29]Ibid, page 178 Having a highly lucrative trade and commerce system, the northern cities, as well as the powerful Papal States around Rome, found it more convenient to pay troops rather than rely on obligated service. [30]Jones. Archer, The Art of War in the Western World, page 178 Their main source of field commanders were mercenary condottieri (as noted above) who would be under contract to raise soldiers for the duration of a campaign. Unfortunately their reliability was doubtful, and their dependability suspect, as they could change sides at the end of their term of contract.

Because of their excellent workmanship in the manufacture of plate armour, the Italians still relied on mounted knights as the mainstay of their armies, being supported by crossbowmen, some pikemen, and shield bearers. Thus tactics were rooted in the old medieval system of infantry being used as mere support and back-up for the cavalry, while artillery remained virtually immobile once placed in a fortified position on the battlefield. Battles were rare and mostly indecisive, with commanders avoiding head-on attacks while attempting to lure their adversaries into traps and ambushes. This avoidance of battle led to an unwritten mutual agreement whereby once realising that the odds were against them soldiers would surrender rather than fight:

Victors usually released rank-and-file prisoners after taking their weapons and horses, which saved the cost of guarding and maintaining the captured soldiers, who would be useless until they had found new equipment. This attitude, like the soldiers preference for becoming a prisoner rather than fighting against great odds, led to criticism of the whole system, including the “scientific” strategy of maneuvers, marches, entrenched camps, and battles in which prisoners predominated among the defeated casualties. But when both sides had the identical culture and followed similar rules, essentially the same stalemate resulted whether or not the combatants had observed a more or less sanguinary mode of warfare. It matters little to the outcome of the conflict, for example, whether both sides release, imprison, or kill prisoners, but, to some contemporary critics, the Italian method seemed unmartial. [31]Jones. Archer, The Art of War in the Western World, page 181

The ambition of King Charles VIII of France knew no bounds, and his war against the Italians did indeed start with some remarkable military successes. In 1494 he invaded Italy with an army of 25,000 men, including a large number of Swiss mercenaries. His artillery was state of the art for its time, having bronze cannon mounted on well constructed wheeled carriages, and although the French never adopted the longbow into their military arsenal, especially knowing its capabilities after the Hundred Years War, they nevertheless had adapted to the military changes that had occurred during the fifteenth century. [32]Ibid, page 183

King Charles conquered Naples, which fell without much trouble owing to the unpopularity of the Neapolitan king, and because Venice had remained neutral, while the Duchy of Milan sided with the French. However the rapid success of Charles’s bold enterprise seriously worried Milan, Venice and the Pope, as well as causing consternation in Spain and with the Holy Roman Emperor. When, in 1495, Charles decided to return to France, leaving half his army to hold down any recurring problems in Naples, he was suddenly confronted by a large Venetian and Milanese army blocking his route through the Apennine Mountains. The resulting battle at Fornovo (6th July 1495) resulted in a stalemate, with the Swiss contingent bearing the brunt of the fighting and showing once again their offensive capabilities.

It was during the early sixteenth century that the Swiss began to lose their predominance on the battlefield, and it was mainly due to condottieri commanders, coupled with their own overconfidence and at times downright insubordination that this occurred. Although proving themselves a capable fighting force at the battle of Novara (6th June 1513), they paid the price for their lack of discipline at Bicocca (27th April 1522), ironically in similar circumstances to the ones they themselves had employed in their early wars. Here the Swiss mercenaries in the service of France, being unpaid and threatening to return to their homeland, demanded an immediate attack against the Spanish/Imperial forces entrenched along a sunken road. They were confident that victory would be theirs, together with the rich pickings in the enemy camp. Forced to concede to this ultimatum the French commander, Odet de Foix, Vicomte de Lautrec, ordered a frontal attack against a prepared position.

Forming themselves into two squares of some 4,000 men each, the Swiss prepared to assault the entrenched line, which consisted of a parapet and bastions studded with artillery, backed up with four lines of arquebusiers, supported by pike men. Intending to soften- up the enemy works with artillery before committing his infantry, Lautrec’s orders were ignored as the impetus Swiss who, refusing to wait for the guns to do their work moved forward, losing almost 1,000 men before reaching the sunken road. When they finally came up against the fire belching enemy entrenchments the Swiss formations were brought to a halt, and began to break-up, as they attempted to climb over the parapet; those who did manage to scramble over were impaled by enemy pike men. After taking a further 2,000 casualties the Swiss quit the field and promptly returned home, ‘shattering the myth of Swiss invincibility.’ [33]Ibid, page 188 Thus the once great exponents of the defensive letzinen had been thwarted at just such an obstacle, albeit one defended by fire power, the new mode of warfare.

During the winter of 1525 the French laid siege to Pavia, once again having a strong contingent of Swiss mercenaries in their army. A Spanish army moved to relive the city, and both sides constructed entrenchments. A cash shortage forced the Spanish commander’s hand, and he was forced to go over to the offensive before many of his mercenaries quit the army due to lack of pay. Finding an unguarded part of the French line the Spanish pushed through, marching in the early hours of the morning and passing around the French entrenchments they formed a defensive line at right angles to their position, knowing full well that the French would attack them rather than risk having their lines of communication compromised. [34]Ibid, page 189 The initial shock of finding the Spanish on their flank did not cause any panic in the French army, and their young king, Francis I, soon began to assemble his forces to attack. Leading his cavalry forward first in order to gain time for the rest of his army to assemble, Francis drove back the Spanish mounted troop and closed with the enemy Landsknechts forming their centre, but these tough heavy infantry stood firm and repulsed the French assault. Francis now sent in his Swiss pike men who manoeuvred against the Spanish flank, which was defended by arquebusiers. Once again the Swiss attack came to a standstill and they fell back, leaving over 1,000 dead and wounded on the field – combined arms tactics, together with a massive increase in firepower now replaced the old manoeuvrable pike square.

It is interesting to quote from a historian of the period who, after the battle of Bicocca wrote, “The Swiss had gone back to their mountains diminished in numbers, but much more diminished in audacity; for it is certain that the losses which they suffered at Bicocca so affected them that in the coming years they no longer displayed their wonted vigor.” [35]Quoted in Archer Jones, The Art of War in the Western World, page 189. The extract is taken from, Roberts. Michael, Gustavus Adolphus: A History of Sweden, 1611- 1632, Volume 2, page 261. London 1958

Graham J.Morris

February 2010

References

| ↑1 | Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 551 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 522 |

| ↑3 | Showalter. D.E, Caste, Skill and Training: The Evolution of Cohesion in European Armies from the Middle Ages to the Sixteenth Century. The Journal of Military History. Vol. 57, page 12 |

| ↑4 | Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 563 |

| ↑5 | Ibid, page 564 |

| ↑6 | Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare. Vol. III, page 564 |

| ↑7, ↑11 | Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300-1500, page 10 |

| ↑8 | Delbrück.Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 572 |

| ↑9 | Delbrück considers the Confederates to have fielded an army of 6,000 – 8,000 |

| ↑10 | Delbrück.Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 573 |

| ↑12 | Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 585 |

| ↑13 | Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300 – 1500, page 13 |

| ↑14 | Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 588-589 |

| ↑15 | Ibid, page 600 – 601 |

| ↑16 | Ibid, page 607 |

| ↑17 | Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare.Vol. III, page 609-610 |

| ↑18 | Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300-1500, page 24. |

| ↑19 | Some of the sources mention 400 cannon abandoned by the Burgundians. This seems far too excessive. Not only is it more guns than Napoleon had at Waterloo, it would also have taken thousands of horses just to bring them, plus their ammunition, to the battlefield. Even if Charles the Bold had lost all of his siege guns, as well as his field artillery, this would have amounted to no more than 100 cannon, and even this figure seems too high. |

| ↑20 | Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare. Vol. III, page 613 |

| ↑21 | Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300-1500, page 26 |

| ↑22 | Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 615 |

| ↑23 | Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300-1500, page 27 |

| ↑24 | Ibid, page 27 |

| ↑25 | Delbrück. Hans, History of the Art of War, Medieval Warfare, Vol. III, page 621 |

| ↑26 | Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300-1500, page 30 |

| ↑27 | Miller. Douglas, The Swiss at War 1300-1500, page 31 |

| ↑28, ↑30 | Jones. Archer, The Art of War in the Western World, page 178 |

| ↑29 | Ibid, page 178 |

| ↑31 | Jones. Archer, The Art of War in the Western World, page 181 |

| ↑32 | Ibid, page 183 |

| ↑33 | Ibid, page 188 |

| ↑34 | Ibid, page 189 |

| ↑35 | Quoted in Archer Jones, The Art of War in the Western World, page 189. The extract is taken from, Roberts. Michael, Gustavus Adolphus: A History of Sweden, 1611- 1632, Volume 2, page 261. London 1958 |

While this is definitely a wonderful read, one can’t help but notice that every piece of text after the header for Morat 1476 (and in fact the paragraph immediately before thr header itself) was italicised. I wonder if it was due to a missing html tag at the end of the second quotation regarding the Battle of Grandson or something?

Glad you pointed this out Brantas, will get Dr Bob to give it the once over!

Thanks for visiting the site!

Fixed

Excellent read. Thank you!

Once again, thank you for your comments Thomas!