The Lessons of the American Civil War and European Cavalry Tactics

Visitors to this site will have noticed that I have made constant use of, ‘ The Art of War’ by William McElwee, who had been Head of Modern Subjects Department at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst. It was during his sojourn at Sandhurst that he met my old friend and mentor, the late Brigadier Peter Young. It was he who advised me to read McElwee’s book, as he thought it gave an excellent account of the way in which the lessons of the American Civil War, particularly in regard to the use of cavalry, had been either totally ignored or disregarded by most European General Staff’s who, up until the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, considered that mass squadrons of mounted men could still be used in the old style on the modern battlefield.

Having now re-read McElwee’s book, and with the benefit of studies in the American Civil War during my time as a student with the American Military University, I have written this article in the hope that others will take the time not only to read McElwee’s work, but also study the tactics employed by American cavalry commanders, as well as those carried out by General Gourko during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877, who certainly noted the changes that took place in America, and the later cavalry operations that took place during the Polish-Russian War of 1919-1920. I have drawn heavily on the available sources, and also made comparisons with the tactics and performance of American cavalry leaders during the Civil War, both in terms of their contribution to cavalry tactics, and their ability to combine the technology of the day with the changing styles of warfare.

The American Experience.

The legacy of the Revolutionary Wars (1775-1783) had left America with a small but well trained cavalry force with its own manual and school of horsemanship. [1]The US Cavalry School is now situated in Methow Valley, Washington State. It gradually developed into a competent and professional arm of the service, seeing action in the early Indian Wars, and during the Mexican War (1846-1847). These experiences should be borne in mind when considering the way in which cavalry was employed during the Civil War, at first by the South, and later by the North.

Originally conforming to European cavalry traditions, the Americans soon realised that, owing to the vastness of the country and the diverse nature of the climate and terrain, it was impractical to continue to follow the style of cavalry tactics employed by European armies. Also, with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, it soon became apparent that to train masses of recruits in the art of using the lance and sabre, while manoeuvring in squadron and regimental close packed ranks, would not be viable. The American cavalry commanders also saw that, with the introduction of the breech-loading rifle, all of these tactics would prove to be an exercise in pure madness, a lesson that the armies of Europe would take many more years to learn. [2]McElwee, William. The Art of War, page 153.

Both the North and South had a ready-made supply of men who had been brought up in the ways and skills of country craft and horsemanship. Many had to rely on their own initiative for their livelihood, as well as having a good knowledge of how to use firearms. But it was in the Confederate States in particular that these talents were more noticeable having, in the main, a more rural economy, which tended their men to having more of an aptitude for country pursuits and field craft. [3]Ibid, page 150.

The American Civil War also saw the potential for using cavalry against an enemy’s railroad system, and both sides used their mounted troops to good effect in cutting and disrupting rail networks by dashing and daring raids.

At the end of 1862 General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederate cavalry was to show just what could be achieved by using raids at a time when the superior manpower of the North was beginning to tell. In December, Union General Ulysses Simpson Grant was making his first move towards the city of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River with some 40,000 troops, while General William Tecumsech Sherman, with another 32,000 more Union soldiers moved by river against Chickasaw Bluffs, just to the North of the city. On 20th December 1862 Forrest hit the railroad between the towns of Bolivar Tennessee and Columbus Kentucky with his 2,500 troopers, and at the same time Confederate General Earl Van Dorn with 3,500 cavalry wrecked Grant’s secondary base at Holly Springs Mississippi. Not content with what had been achieved by his first raid, Forrest now took his force even further afield cutting Grant’s only rail link to the North between Humbolt and Jackson Tennessee. He caused so much destruction to track, bridges and rolling stock far into Kentucky that Grant was forced to retire back to Holly Springs and abandon his campaign for want of supplies and communications. [4]Ibid, page 155. But the main factor of Forrest’s raids, which were to become even more frustrating to Sherman later in the war, was that he had managed to tie down thousands of Union troops in attempts to intercept him.

It was during Sherman’s 1864 campaign against Atlanta Georgia that Forrest really excelled himself as an independent and intuitive commander.

‘His mere presence with a few thousand cavalry to the south forced Sherman to leave 80,000 of his 180,000 men he had with him to guard his line of communication to his main supply base at Louisville which lengthened as he advanced to 340 miles. Sherman had insured himself against temporary delays caused by attacks on his advance depots or minor damage to the railway immediately behind his main army. But Forrest, back at Tupelo in Mississippi, was nicely placed for a destructive raid on the northernmost sector of his railway which would cut Sherman off from his main base and in the long run bring his campaign to a halt…He (Sherman) therefore detached a mixed force of a further 10,000 under General Sturgis to hunt Forrest out of Tupelo and drive him to the west, out of harm’s way. At that very moment Forrest had set out to do just what Sherman most feared; and Sturgis did at least bring him hurrying back to save his base and troops he had left there. Though outnumbered by more than three to one, Forrest brilliantly concealed his weakness by moving through thickly wooded country, caught Sturgis at Brice’s Cross Roads with his cavalry and infantry widely separated and inflicted on him a smashing defeat. As Sturgis fell back to Memphis, he left 2,500 men -a quarter of his army- dead or wounded on the field; and Forrest got back to Tupelo having suffered no more than 500 casualties’. [5]McElwee, William. The Art of War, page 156.

Although not on the scale of Forrest’s raids, the Union did succeed in diverting Confederate attention away from Grants second advance on Vicksburg when, in April 1863, General Benjamin Henry Grierson took 1,700 Union cavalry on a raid south of the city. This raid proved most beneficial to Grant as his forces crossed the Mississippi, but caused panic in the South, ultimately resulting in their president, Jefferson Davis trying to hold on to Vicksburg at any cost, while also attempting to support Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s forces in Tennessee. The real value of the raid therefore was in distracting and demoralising both the Confederate government and its General commanding Vicksburg, John Clifford Pemberton, at the very moment that Grant was manoeuvring to lay siege to the city. [6]McElwee, William. The Art of War, page 155-156.

It was the American generals who turned to an entirely new technique in their use of cavalry. A large force of mounted troops soon became a component of a lightly equipped force of all arms capable of operating against an enemy’s flank or rear. Speed, surprise and secrecy were the necessary elements in these operations. Used as a covering force the cavalry could mask the movements of a corps or an army, and it could also be used to threaten so many points simultaneously that the enemy were left guessing as to their true intent. [7]Ibid, page 159

Perhaps the best example of how combined arms could be used to best effect came in the last year of the Civil War. At the beginning of 1865 General Robert E. Lee was being forced to stretch his dwindling forces further to his right, in order to cover the city of Richmond in Virginia. General George Pickett, the ill-fated commander whose division was decimated at Gettysburg, was detached by Lee from his position around Petersburg and pushed out to cover the Confederate right flank at Five Forks. It was here that poor old Pickett clashed with the Union cavalry under General Phil Sheridan.

On the 31st March 1865 Sheridan pushed out one of his cavalry divisions, commanded by General Thomas Casimer Devin, towards Five Forks. In torrential rain the Union troopers made steady progress, but Pickett had found a road that ran through thick woods towards Dinwidde Court House, which concealed his forces from the enemy, enabling them to manoeuvre around the Union left flank with the idea of cutting them off. In so doing Pickett managed to drive a wedge between Devin’s division and Sheridan’s other Federal cavalry. [8]Morris. Roy, Jr. Sheridan, The Life and Wars of General Phil Sheridan, page 245-246.

Taking stock of the situation, Sheridan immediately organised his other divisions to meet Pickett’s threat, eventually causing the Confederates to pull back from Dinnwidde and form a defensive line less then a hundred meters from the Union position. [9]Ibid, page 246.

Meanwhile Grant, now in command of all Union forces, and present with the Army of the Potomac on Lee’s front, ordered Sheridan to assume command of all troops to be sent to operate with him, these included the Union V Corps under General Gouverneur Kemble Warren.

Warren’s behaviour during the battle is another story. It was Sheridan’s, ‘…masterly demonstration of the power of a mixed force of all arms when intelligently employed,’ [10]McElwee, William, The Art of War, page 161. that is the real object of study. As McElwee says, ‘ His dismounted cavalry went over to the offensive and pinned down Pickett’s main force, while the infantry prised open the gap which had opened between Lee’s main army and his detached wing. By the end of the day Pickett’s force had been rolled up and dispersed in wild disorder and Lee’s main position rendered untenable.’ [11]Ibid, page 161.

Concerning Sheridan’s use of a mixed force at Five Forks, Major Henry Havelock a British commentator, had this to say, ‘Had it been any European Cavalry, unarmed with “repeaters”, and untrained to fight on foot, that was barring the way -any Cavalry whose only means of detention consisted in the absurd ineffectual fire of mounted skirmishers, or in repeated charges with lance and sabre- the Confederate game would have been simple and easy enough.’ [12]Quoted in, Lawford, James. Editor. The Cavalry, page 163.

Havelock himself had won the Victoria Cross at Cawnpore in India in 1858, and although he was not in America to view the Civil War at first hand, he nevertheless understood by his studies of that conflict that what the American cavalry leaders had achieved were in complete harmony with his own conclusions on how cavalry should be handled, ‘ His final and fanatically held view was that in territory open enough to allow room for manoeuvre and in face of the rising fire-power of modern infantry and artillery “sabre cavalry” were totally out of date. He preached his conclusion with a fervid intolerance which, though it did no damage to his military career, made them totally suspect to higher authority.’ [13]McElwee, William. The Art of War, page 172

As well as Havelock, another exponent of change in cavalry tactics came from the writings of the Canadian born, Lieutenant-Colonel George T.Denison. After the American Civil War Denison interviewed a number of Confederate generals who were living in exile in Canada. From these talks he concluded that, although there was a need to retain some cavalry units in their traditional role, fire-power should now be the main factor in the training of the mounted arm of the service, utilising the horse only for greater mobility. [14]Ibid, page 172 His theories may not have been taken very seriously by most European powers, but he did win the first prize, offered by the Russian Grand Duke Nicholas in 1874, for his essay on the history of cavalry. [15]McElwee. William. The Art of War, page 172

Even with the glaringly obvious fact that, after Borodino, Waterloo and Balaclava, cavalry could not, on their own, be expected to break well-formed infantry squares or overrun entrenchments, the armies of Europe still persisted in the old fashioned methods of dividing their mounted troops into light and heavy units, each trained in the skills of either the sword or the lance, and although the pistol or carbine were issued to both categories, these were considered as secondary to the use of cold steel.

The Prussians soon learnt their lesson regarding the poor showing of their cavalry during the war with Austria in 1866, but even allowing for their greater preponderance over the French in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, they still managed, albeit on a spectacular scale, to loose over half a brigade of cavalry when General von Bredow was ordered to charge the French infantry and gun line at the battle of Mars-la-Tours (16th August 1870). That the charge itself did indeed stabilize the situation for the Prussians is not in question, what it should have shown to all those who witnessed it, and to those who studied its effects thereafter, was that if all cavalry were now to be used as little more than suicide missiles, then some other means of utilising these expensive and well disciplined troops should now be seriously considered.

Gourko

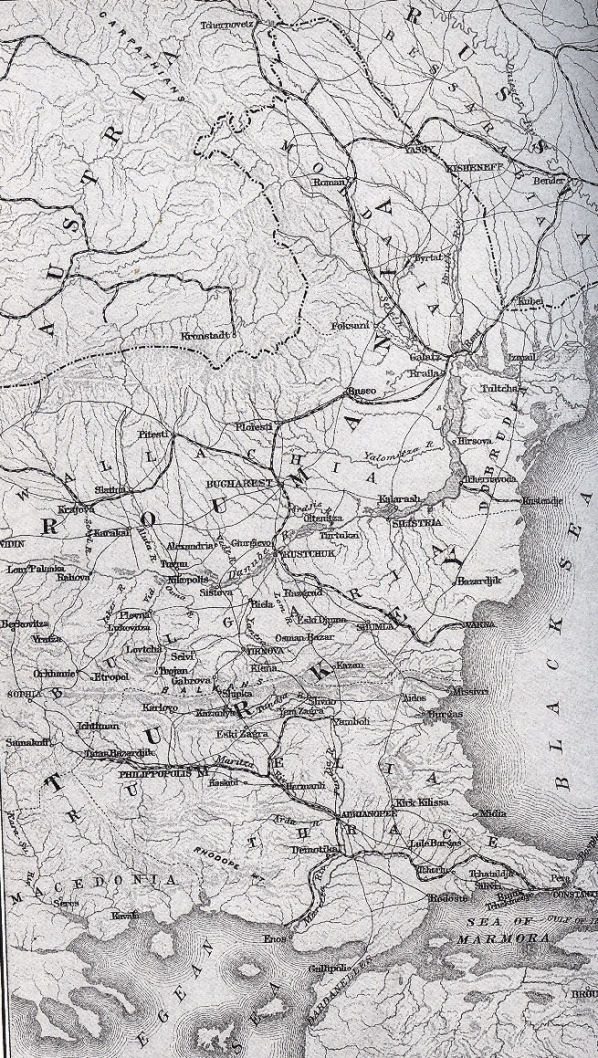

Although the Russo-Turkish War of 1877 has been relegated to no more than just another incident in the troubled history of the Balkans, it did make one outstanding contribution to the knowledge of combined arms warfare, and in particular to the use, instead of abuse, of cavalry.

The small subsidiary operation conducted by the Russian advance guard commander, General Joseph Vladimirovich Gourko, in which he advanced from the River Danube and captured the Turkish stronghold at the Shipka Pass with a mixed force of some 8,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry and 32 guns, was nothing short of an object lesson in what could be achieved by sound planning and the brilliant coordination of his forces.

Born in 1828, Gourko was educated in the Imperial Corps of Pages. He joined the Hussars of the Imperial bodyguard as a second lieutenant in 1846, and thereafter became its captain in 1857. In 1860 Gourko was employed on the Emperors staff as adjutant, and then, in 1861 as colonel. He then took command of the Mariupol Hussars in 1866, and was promoted to Major General on the Emperors suite in 1867. Taking command of a guard grenadier regiment in 1870, he subsequently transferred to the guard cavalry where he led the 1st brigade of the 1st guard cavalry division in 1873. It can be seen from this that, although he did not take an active part in the Crimean War, he had a good working knowledge of both infantry and cavalry.

Gourko’s campaign in which he manoeuvred his little mixed force across and around torturous mountain tracks, outflanking the Turkish forces at the Shipka Pass, to fall on their rear, while the Russian VIII corps engaged them frontally, is fully covered in First Lieutenant F.V.Greene’s work, ‘Russian Campaigns in Turkey 1877-1878.’ The real point of interest is the composition of Gourko’s forces and the methods he used in employing his mounted troops which, ‘…was clearly based on thorough and intelligent study of the great cavalry sweeps of the American Civil War.’ [16]McElwee. William, The Art of War, page 197

As well has having one regular cavalry brigade, consisting of two regiments of Dragoons and a horse battery, Gourko also had a mixed brigade of Hussars and Cossacks together with a Cossack horse battery. In addition he had a detachment of mounted pioneers made up of Don, Caucasus and Ural Cossacks who were specially trained in demolition and engineering skills. His regular cavalry, armed with the shortened Berdan rifle to which a bayonet could be fitted, had been fully trained to act as mounted infantry, and were so adaptable that they were just as much at home being employed as light infantry as they were being used for quick mounted raid against an enemy’s flank.

His advance guard took the town of Trinova in central Bulgaria on July 7th 1877. The town itself was a natural fortress situated in a bend of the river Yantra on its left bank, surrounded by rocky cliffs rising over 500 feet above the town. As Gourko’s troops approached from the western passes the Turks pulled back to cover the town. They had some 3,000 infantry supported by six guns, and some 400 Bashi-Bazouk irregular cavalry who were very unreliable. Correctly gauging that speed was of the essence, Gourko quickly opened up on the Turkish positions with his horse battery, while these guns were going into action he bought up four squadrons of Cossacks with orders to work their way around the Turkish flank and come at them from the rear. He then dismounted his regular brigade of Dragoons and sent them forward in a direct assault on the town itself. These tactics proved so effective that, with only 1,400 men, and with his regular cavalry on foot, the Turks broke and fled. Thus at the cost of two men and eight horses wounded Gourko had taken a key point in the Turkish lines, had captured enough food and forage to last him for the remainder of the campaign, and supplied the Russian Grand Duke Nicholas with a base for his headquarters. [17]McElwee. William, The Art of War, page 198

With Trinova secured Gourko now pressed on and captured Hainkoi, Uflani, Maglish and Kazanlyk. On the 18th of July he attacked the Shipka itself, which was hastily evacuated by the Turks on the following day. In the sixteen days since crossing the Danube, Gourko had cleared and secured three Balkan passes and caused consternation in Constantinople. Not one to rest on his laurels, Gourko now took his troops on a reconnaissance raid into the Tunja valley. Here he cut the railway line in two places, occupied Stara Zagora and Nova Zagora, bought the main Turkish army under Suleiman to a halt, and then proceeded to re-cross the Balkans leaving chaos in his wake. As McElwee states:

‘Gourko had thus demonstrated one lesson which the rest of the world’s armies were very slow to learn: that cavalry still had an enormous potential value in country where there was plenty of room to manoeuvre, provided that they would forget the legendary charges of history, exploit their mobility to the limit, and train themselves to do their fighting on foot. In the course of his subsequent and highly successful operations he was to teach two more…Gourko’s enterprising cavalry patrols deep into enemy territory not only kept him informed of Turkish dispositions on his own immediate front, but enabled him to keep the Grand Duke Nicholas posted on every phase of the concentration of the main Turkish army in Roumelia and its advance to what was to prove the decisive winter battles of the south of Shipka…Finally Gourko, alone among the generals of his age, had digested what was, perhaps, the supreme lesson of the American Civil War: the value of powerful cavalry raids deep into the enemy’s territory to disrupt their communications and interrupt their supplies.’ [18]McElwee. William, The Art of War, page 198-199

Allenby

The British contribution to cavalry tactics, or lack thereof, has been dealt with elsewhere on this site, suffice to say that, even allowing for the fact that the British cavalry eventually took to using the rifle instead of the sword or lance, the latter being withdrawn from service in 1903, the old diehards who made-up the Imperial General Staff were still of the opinion that once a breakthrough had been achieved then the lance should be the weapons to prod the enemy along. Thus, in 1907 the lance was once more reintroduced, ‘…and so matters stood in 1914 when the 16th Lancers rode across France with their lances swinging round their backs.’ [19]Lawford. Colonel James, The Cavalry, page 172

The Western Front was to prove how ineffectual cavalry had become when faced by mud, wire and machineguns, however there was one place that still harboured the possibility of using mounted troops in something like the old style. The British had been forced to send an army over to Egypt to protect the vital Suez Canal from the Turks and also crush insurrection in the Western Desert. The cavalry composition of the army was made up from Australian Light Horse, New Zealand Mounted Rifles and British Yeomanry regiments, the latter still carrying the sabre, which they had managed to retain, ‘exploiting an oversight in high places.’ [20]Ibid, page 172

In 1917 General Allenby, a stalwart cavalryman himself, took over command of the forces in Egypt, forming his mounted troops into three divisions each of three brigades containing three regiments and a machine-gun squadron with 12 Vickers machineguns.

On the 30th October 1917 Allenby had a combined force of some 58,000 infantry and cavalry supported by 242 guns poised to strike the Turkish position around the town of Beersheba in Palestine. With great skill he manoeuvred his army by night eastward for the assault on the town, a very difficult operation carried out across a featureless landscape. Dawn on the 31st October saw the Australian Light Horse advancing in open order toward the Turkish trenches. Suddenly their artillery opened fire, and their machineguns began to chatter into action. An effective counter fire was laid down by Allenby’s horse batteries, which silenced the Turkish guns allowing the Australians to press-on taking casualties from Turkish rifle fire. Undeterred, the Aussie’s broke into a gallop, took both lines of Turkish trenches and, ‘Some Australians then dismounted to settle matters with the rifle and bayonet while others dashed on into Beersheba spreading terror and panic.’ [21]Lawford, Colonel James. The Cavalry, page 173

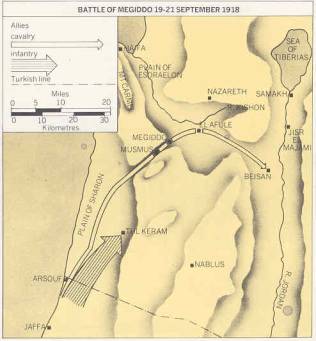

At the Battle of Megiddo in September 1918 Allenby also made much use of his cavalry, which now contained many Indian units, much of the British Yeomanry regiments being shipped back to France in the face of the great German offensive. The Turks were once again completely wrong footed as to where the attack would fall. After just three hours the Turkish front, some 65 miles in length, was pierced and Allenby’s cavalry swept through towards Megiddo, wheeling to the right as they did so as to block the retreat of the Turkish 7th and 8th Armies.

During the rapid retreat of the Turks, one particular incident that would have warmed the hearts of both Bedford Forrest and Phil Sheridan occurred when the Fifth Cavalry attacked the town of Haifa, which the Turks went to some pains to defend. On the 23rd September Allenby’s 5th Cavalry Division approached the town and was ordered to take-out a strong Turkish artillery position on Mount Carmel overlooking Haifa. While a squadron of the Mysore Lances, reinforced by a squadron of the Sherwood Ranges prepared to move on the heights, the Jodhpur Lances, together with the remaining Mysore squadrons went in against the town, encountering Turkish positions blocking the road:

‘The leading regiment and machine-guns acted as a fire pivot, the battery fired on the enemy positions, and one regiment was sent from about three miles behind to gallop the place. It was a ticklish situation as an impassable stream…forced them to wheel to the left and go through the narrow defile along the main road. However, a stout-hearted body of men on galloping horses takes a lot of stopping and, within half an hour from the word ‘go’. Haifa was ours.’ [22]Quoted in Anthony Bruce, The Last Crusade, The Palestine Campaign in the First World War, page 235

While this attack was taking place the squadrons sent to Mount Carmel charged the Turkish artillery capturing 17 guns and 1,350 prisoners, a truly magnificent performance by mounted troops.

The ‘Konarmiya’

The Russian Revolution of 1917 caused the fragmentation of the old Romanov Empire, and although peace with Germany was attained in 1918, internal strife and counter-revolution threatened to undermine the Bolshevik party’s grasp on the reins of power. On fifteen fronts Soviet Russia was fighting a life or death struggle with the ‘White’ armies of Denikin, Kolchak, Yudenich, with the British in Archangel, Murmansk and the Caucasus, the French in Odessa, and the Americans and Japanese in Vladivostok. [23]Davis. Norman, White Eagle Red Star, page 21

With Germany’s surrender in 1918, and their withdrawal from their enclave in Ober-Ost the new Polish Republic under the charismatic leadership of Józef Pilsudski sort to re-establish control over what it saw as lands taken away when the Kingdom of Poland had been dismantled in 1795. For the Poles the Borders were, ‘…the outpost of Christendom, warring with the Turks and the Tartars in defence of the Faith, and with the Muscovites for a sway of the steppes.’ [24]Ibid, page 29 As for the Bolsheviks they saw the Borders as a gateway into Europe through which their revolutionary dogma could be unleashed on the war-weary capitalist nations of the west.

The Polish-Soviet War of 1920 saw both sides in a state of chaos and uncertainty. As General Fuller states, ‘Both were improvised, chaotically equipped and suffered from over- rapid growth…Though manpower was sufficient, Poland possessed no arsenals and lacked munitions…(The Russian Army) Is a horde, and its strength is that of a horde.’ [25]Fuller. General J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol III, page 340

Those who had to face the Soviet First Cavalry Army (the Konarmiya) quickly learnt just what this “horde” was capable of, and I quote here at length from Norman Davis’s account of this formidable organisation

The First Cavalry Army (the Konarmiya) was the most successful innovation of the Civil War. Formed in November 1919, it was the logical outcome of warfare with the White armies, in which the Reds had proved themselves equal to everything except the Cossack cavalry. By massing all available sabres into one formation, it enjoyed not only the famous Cossack mobility and esprit de corps but also overwhelming weight and numbers at any point where it was applied. It waged a form of Tartar blitzkrieg. It welcomed all who could ride and obey, who were ready to saddle and march to any point in the continent where the Revolution was in danger. It was the ultimate antithesis of the original localized, class conscious, footslogging Red Guards of 1918.

Semyon Mikhaylovich Budyonny typified the best of the men he served. He was a man who thrived on hard times through his skill as a soldier and by force of personality. The son of a poor farmer in Rostov province, he joined the 43rd Cossack Regiment in 1903 and served in Manchuria before graduating from the Petersburg Riding School. In the summer of 1917, chairman of the soviet of his mutinous regiment, he found himself at Minsk, where Frunze and Myasnikov were organizing resistance to Kornilov. From there he made his way as a Red cavalry commander. He first attracted notice at Tsaritsyn in December 1918, when his daring and enterprise recommended him to Voroshilov. He was the obvious choice to lead the ‘Konarmiya’. Very tall, very athletic, he was a breathtaking horseman, who led from the front. His fine Asiatic features, his superb black moustache, curled and groomed like the main of a showhorse, his steady almond eyes revealed the perfect man of action-a prime animal, a magnificent, semi-literate son of the steppes. 25 April 1920, the day the Kiev campaign was launched, was his fortieth birthday.

The troopers of the Konarmiya had little in common with Bolshevik politics, except that they were fighting on the same side. Most of them were former Cossacks, partisans, and bandits, won over in the course of the Red Army’s victories. Yet they understood Revolution perfectly. They approached the thoughts of Lenin and the concepts of Marxism more with awe than with understanding. There were one or two literates, like Isaak Babel* in the 1st Brigade of the 6th Division, or Zhukov, the future Marshal. But by and large they were more distinguished in heroics than in dialectics. In the eyes of the Poles, they were the reincarnation of the hordes of Genghis Khan. [26]Davis. Norman, White Eagle, Red Star, page 116-117. * Isaac Bable (1894-1940) wrote a fascinating account of the Konarmiya in his book, Red Cavalry.

After crushing the ‘White’ Russian forces under Denikin in the Caucasus, the Konarmiya had been ordered to the Polish front in April 1920. Within two weeks it was crossing the River Don into Rostov where Budyonny quelled a riot in the ranks due to faction of the Konarmiya whose former leader, Dumenko, had just been liberated from prison. Order was restored and, after sacking Rostov the Konarmiya split into columns to continue its march:

Gorodovikov’s 4th Division, Timoshenko’s 6th, Morozov’s 11th, and Parkomenko’s 14th. Their four armoured trains, three air squadrons, and other support services were dispatched by rail through central Russia. They themselves went overland. Leaving Rostov on 23 April they gave themselves a fortnight to reach the (River) Dnieper. They travelled in column, resting and riding in turns. They pulled the sick and tired behind them in carts, along with the artillery. They shot the horses lamed by the pace at the rate of a dozen a day. In the daytime the front ranks carried letter-boards on their backs to teach the ranks behind to read…At the end of April, with news of the Polish offensive, they received orders to quicken their pace. They were in Makhon country, where for months past a murderous war for the life and soul of the peasantry had been in progress Cheka squads were touring the villages, hanging partisans and installing soviets. Makhano was following them, shooting communists and ambushing Red Army forage parties. On 28 April the 14th Division stormed Gulaypolye, ‘Markhanograd’ itself, routing a force of some 2,000 partisans. The Konarmiya rode on regardless, like a ship of the line driving through a fleet of fishing smacks. [27]Davis. Norman, White Eagle, Red Star, page 119

The subsequent campaign against the Poles was to prove how adaptable the Konarmiya could be when properly led. Knowing that to attack entrenched positions with mounted troops was nothing short of glorified suicide, Budyonny dismounted part of his force and approached the enemy in open formation, with massive artillery support, while trained groups took-out any fortified strongpoints. The remaining mounted units, because of the vastness of the terrain to be held, could normally find an open flank and then role-up the enemy line. [28]Ibid, page 123

What might have occurred had the Soviet leadership been united in its military decision making, as well as in its overall policy concerning the war as a whole, is made glaringly obvious when one reads Pilsudski’s writings. The Polish leader was well aware of the power of the Konarmiya, as well as the amazing abilities and qualities of the Russian General Mikail Tukhachevski, who commanded the Russian Army of the West. By a combination of muddle-minded decisions, petty jealousies, and power crazed over rulings, men like Stalin, Trotsky, Kamenev, and even Lenin himself, managed to throw away all that had been gained at the very gates of Warsaw. What does remain remarkable is the fact that, even allowing for the massive increase in firepower on the battlefield, the horse soldier could still pose a threat, both psychological and real to the armies of the twentieth century. Old Bedford Forrest would have been happy to know that his way of fighting was still being used to good effect by those who had understood and imbibed his way of waging war.

Graham J. Morris

June 2004

Bibliography

Babel. Issac, Red Cavalry, paperback edition, W.W.Norton, New York and London, 2003

Bruce.Anthony, The Last Crusade, The Palestine Campaign in the First World War, paperback edition, John Murray Publishers, London, 2003

Davis. Norman, White Eagle, Red Star, The Polish-Soviet War 1919-1920, And the ‘Miracle on the Vistula,’ paperback edition, Pimlico Press, London, 2003

Fuller. General J.F.C., The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Volume III, Eyre and Spottiswoode, London, 1957

Green. F.V.Report on the Russian Army and Its Campaign in Turkey in 1877-1878, Battery Press, Nashville, 1996

Lawford.Colonel James (editor), The Cavalry, Roxby Press, London, 1976

McElwee. William, The Art of War, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1974

Morris. Roy, Jr., Sheridan, The Life and Wars of General Phil Sheridan, paperback edition, Vintage Civil War Library, New York, 1993

See also: Pilsudski. J, ‘Rok 1920’. Fifth Impression, London, 1941

Note on Photograph of the Konarmiya:

I have tried to find the source of this photograph, which is shown in Norman Davis’s book, White Eagle, Red Star. Davis himself, and his publishes, do not give any reference to where they obtained this photograph, and I have endeavoured to search various archives to obtain permission to use the photograph on this site, all to no avail. I will be pleased to contact copyright holders and obtain their permission if it is thought that any infringement of copyright has been made.

References

| ↑1 | The US Cavalry School is now situated in Methow Valley, Washington State. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | McElwee, William. The Art of War, page 153. |

| ↑3 | Ibid, page 150. |

| ↑4 | Ibid, page 155. |

| ↑5 | McElwee, William. The Art of War, page 156. |

| ↑6 | McElwee, William. The Art of War, page 155-156. |

| ↑7 | Ibid, page 159 |

| ↑8 | Morris. Roy, Jr. Sheridan, The Life and Wars of General Phil Sheridan, page 245-246. |

| ↑9 | Ibid, page 246. |

| ↑10 | McElwee, William, The Art of War, page 161. |

| ↑11 | Ibid, page 161. |

| ↑12 | Quoted in, Lawford, James. Editor. The Cavalry, page 163. |

| ↑13 | McElwee, William. The Art of War, page 172 |

| ↑14, ↑20 | Ibid, page 172 |

| ↑15 | McElwee. William. The Art of War, page 172 |

| ↑16 | McElwee. William, The Art of War, page 197 |

| ↑17 | McElwee. William, The Art of War, page 198 |

| ↑18 | McElwee. William, The Art of War, page 198-199 |

| ↑19 | Lawford. Colonel James, The Cavalry, page 172 |

| ↑21 | Lawford, Colonel James. The Cavalry, page 173 |

| ↑22 | Quoted in Anthony Bruce, The Last Crusade, The Palestine Campaign in the First World War, page 235 |

| ↑23 | Davis. Norman, White Eagle Red Star, page 21 |

| ↑24 | Ibid, page 29 |

| ↑25 | Fuller. General J.F.C. The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Vol III, page 340 |

| ↑26 | Davis. Norman, White Eagle, Red Star, page 116-117. * Isaac Bable (1894-1940) wrote a fascinating account of the Konarmiya in his book, Red Cavalry. |

| ↑27 | Davis. Norman, White Eagle, Red Star, page 119 |

| ↑28 | Ibid, page 123 |

Dear A.B.Brantas,

Thank you for your comment concerning cavalry, both during and after the American Civil War.

I would be very interested in what you have to say with regard to European cavalry during this period.

Regards,

Graham J.Morris (battlefieldanomalies)

I believe we can get this page categorised into the… IDK, I tend to go General with this rather than American Civil War (seeing that the point of this post is what the Americans — both Union and Confederate — realised about cavalry in the post-Napoleonic era, and how slowly the European brass in general [pun not intended] realise the same point, outliers like Gourko and Havelock notwithstanding)?

Now also under general.